What Happens When You Leave The Yakuza?

Few crime syndicates have captured the imagination like the yakuza. Maybe it's the group's colorful, bold-lined, full-body tattoos, evocative of traditional ukiyo-e woodblock prints. Maybe it's the mystique of Japan, a nation intertwined with all sorts of romanticized visions of samurai, anime, downtown Tokyo neon lights, etc. Maybe it's all the yakuza's severed fingers. But no matter how mythical, it's a very real option for disaffected Japanese youths. Joining is easy, and sometimes so is leaving. But after a person leaves, life remains difficult, just in a different way.

For many yakuza, life after gangsterism unfolds like it might for many ex-cons: Trying to find a way to fit in. Some former yakuza, like Yoshimoto Morohashi and Ryuichi Komura, studied to get some kind of certification while in prison and then left the group to pursue a different life. Others, like Yuyama Shinya, had some kind of epiphany before departing. Others talk about how hard it is to reintegrate into society as a "law-abiding citizen," a common theme amongst former yakuza testimonials. Those with ties with criminal organizations have severely restricted options and choices in Japan. They can't have a bank account, get a loan, sign a rental agreement, and more. In many ways, members of yakuza are bonded for life.

Beyond such generalities, it's impossible to make blanket statements about the lives of all former yakuza. Most aren't willing to speak with the public, and data isn't forthcoming. But those who leave the yakuza are free to live their lives as they can and wish, no matter that they'll always carry their past with them.

Exiting the yakuza — or just running away

The first step to starting a post-yakuza life is leaving the yakuza. Specifics regarding exiting the group are scarce and anecdotal. But as former yakuza and waka gashira (second-in-command) Shinya Yuyama said in an extended Insider exposé, there are as many ways to leave the yakuza as there are people in the yakuza. There's no set method, and there are different obstacles or requirements for each person who wants to leave. Also, each yakuza cell is different and operates under its own boss no matter the umbrella term "yakuza." So, leaving really depends on the boss' preference. Yuyama says he had a good relationship with his boss. Even so, he doesn't say exactly what he had to do to leave, which is telling in and of itself.

We can clarify one potential misconception, though, related to cutting off fingers. It's somewhat common knowledge that yakuza members can be identified through missing pinkies. It's true that members who've broken rules or displeased superiors engage in ritual amputation called "yubitsume." The severed digit gets submitted to one's boss, who might bury it, freeze it, enshrine it, etc. But despite what some might suggest, this doesn't happen as payment for leaving the yakuza.

Yuyama told Insider that it's more common for people to leave the yakuza by vanishing rather than by stating their desire to leave the organization. Although this might seem fairly straightforward, it's possibly more dangerous than officially exiting. Why? Because in this scenario, there's nothing stopping the group from tracking a runaway member.

The difficulties of starting a new life

Much like other countries, criminals in Japan face a steep climb reintegrating into society. Sometimes it's a simple matter of fear from the general public, and sometimes it's restricted legal choices based on an affiliation with a criminal enterprise. Sometimes it's fear on the part of the yakuza who left the organization.

As The Asahi Shimbun quotes an unnamed former yakuza: "I was concerned whether someone like me, who has been a member of a gang for a long time, could really live in normal society." Leaving and starting a new life was especially difficult because he'd risen in rank and made a name for himself, owed favors to people, developed ties to them, and so forth. At present, he's tried to change everything about himself, down to his accent, word choice, gait, mannerisms, and more. Still, some neighbors know who he used to be.

Each former yakuza seems to take a different path after leaving the gang. Yoshitomo Morohashi took seven years of study to pass multiple exams, including a bar exam, starting in prison. Ryuichi Komura also started studying in prison and took eight years to pass a judicial scrivener exam — he hadn't gotten any education past junior high school until then. Tatsuya Shindo, meanwhile, went to seminary and became a priest. Then there's Magomi Hashimoto, who got into politics. As a fourth generation "zainichi" — descended from ethnically Korean people who were often marginalized in Japan's past — Hashimoto got roped into the yakuza at a young age through his mother. On and on it goes, and each situation is as unique as the last.

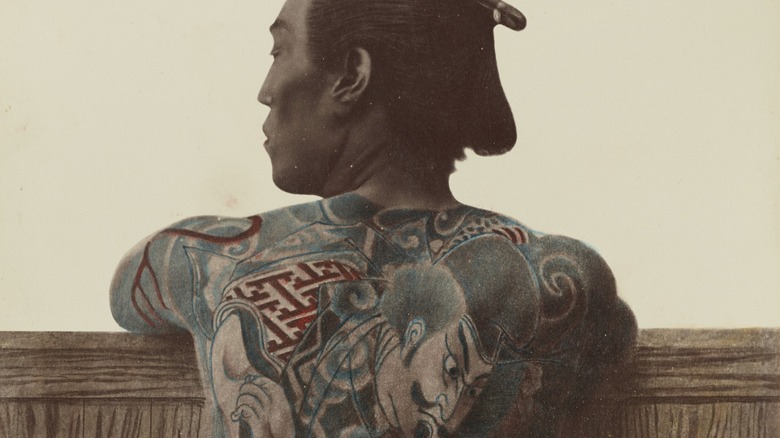

The stigma of tattoos in Japan

Out of all the challenges that a former yakuza faces, the reader might be inclined to think that the presence of tattoos is low on the list. While it's not as much of a hindrance to a law-abiding life in Japan as having ties to a criminal organization, it presents more barriers than one might think. A foreigner with tattoos who goes to a public bath house, for example, might get a pass simply for being a foreigner. But a Japanese person with tattoos, especially on the arm sleeves or torso? That means yakuza. As Yuyama Shinya told Insider, tattoos indicate a desire to intimidate another person. They're also an impediment to getting involved in many professions. Note that Shinya got his tattoos removed from his wrists to halfway up his forearms. Otherwise, they might be visible even when wearing a long-sleeve shirt or business suit.

That being said, not all yakuza have tattoos. But the longer someone is in the group, the more likely they are to sprawl. Traditional tattoo artist Horiyoshi 3 — who was tattooing a yakuza during his interviewer's visit — told Vice that he never works on the face or hands because "beauty is in what you can't see." Each design he inscribes is a personalized story full of symbolic items like koi, which swim against the stream and represent overcoming adversity. But even those stories will have to be covered or erased if a former yakuza wishes to integrate into non-criminal society after leaving the organization.