Things That Don't Make Sense About The American Civil War

The United States' grinding, bloody four-year civil war has lived on in the public imagination since the last shots were fired. It's been romanticized as a glamourous struggle for Southern independence (see "Gone with the Wind"), dissected in detail in documentary after documentary, and led to public debates about how the war should be remembered even during the 2020s. An observer could honestly conclude that nothing unites Americans as well as fighting each other, either on the battlefield or in the court of public opinion.

Even for a chapter of history as frequently (and as hotly) discussed as the American Civil War, questions remain. We know what happened, and usually we know why ... but not always. Strange decisions, unexpected outcomes, and downright baffling events will inevitably pepper the history of a long, complex conflict. Even 160 years later, there are aspects of the Civil War that just don't really make sense, at least in retrospect.

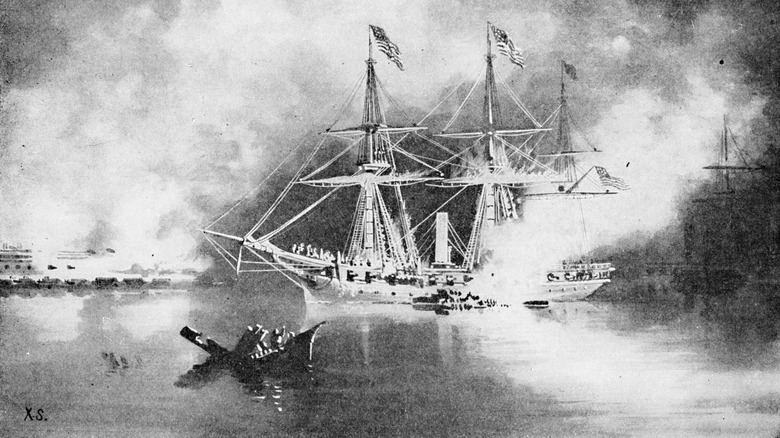

Why wasn't the Confederacy's richest and most populous city better defended?

When Louisiana joined the emerging Confederacy in early 1861, it brought with it the thriving port of New Orleans, a wealthy and populous city that would (briefly) be the largest in the would-be nation. "Briefly" because New Orleans would be captured first of all the major cities in the South, surrendering to Union forces in April 1862. Its fall was among the Union's most important early victories (and among the biggest blunders by either side in the entire Civil War). The Confederacy now looked incompetent and had lost one of its greatest assets, additionally setting up the Union to start clawing back control of the Mississippi River from both directions. (The Union also snagged $800,000 in gold stored in the Dutch consul's office — no small potatoes.)

How had the Confederacy biffed so hard? New Orleans had few defenses around the town itself, instead relying for protection on Forts Jackson and St. Philip, two small fortifications downstream on the Mississippi River that could fire on any ships trying to move north toward the city. Additionally, a heavy chain could be stretched across the river to foil attempts to navigate it. A Union naval force under Captain David Farragut was able to break the chain and send most of its boats through the gauntlet, while gunships fired on the Confederate forts to limit their ability to respond. This bold but ultimately basic strategy worked, and New Orleans fell into Union hands like a freshly fried beignet.

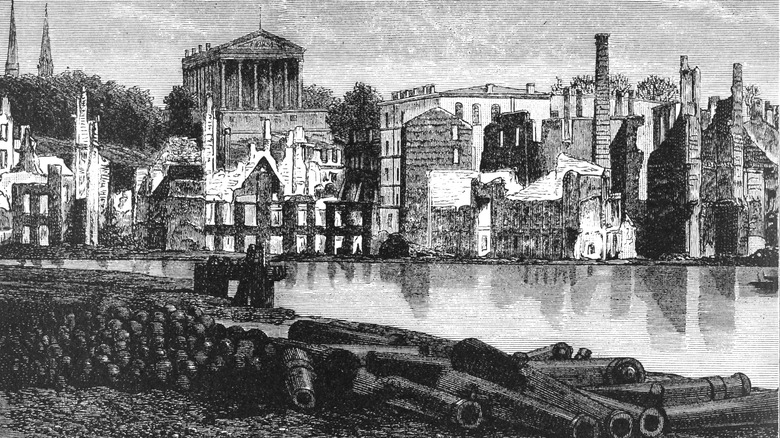

Why was the Confederate capital so close to Washington?

Despite the District of Columbia sharing a border with Confederate Virginia, the U.S. capital stayed in Washington during the war. For its part, the Confederacy originally set up its government in Montgomery, Alabama, far from the emerging border and a safe distance from Union forces. Once Virginia seceded, however, the Confederacy moved its capital to Richmond, the state capital of Virginia, and kept it there until shortly before the end of the war (Danville, Virginia, replaced it for eight frantic days in April 1865). Why move the capital of a fledgling rebel movement a mere 108 miles from the seat of the Federal government?

The short answer seems to be that Virginia was important. Richmond was the second largest city in the Confederacy (after New Orleans) and relatively industrial, so it brought needed factories to the agricultural South's war effort. Virginia was also heavily associated with the colonial era and the Revolution, so it was somewhat of a "catch" for the South. (Virginia also had the largest Black population of any at the time: largely, of course, enslaved.) The people of Virginia would pay a heavy price for the defiant, even sassy placement of the Confederate capital. Northern Virginia was one of the most horrific meat grinders of the war, and by the war's end, Richmond itself lay largely in ruins.

How was the US paying a veteran's civil war pension until 2020?

The Civil War ended in 1865, so even the very youngest veterans would have been lucky to reach the middle of the next century — yet two long lives meant that the United States was paying a Civil War-related pension until 2020. In May 2020, 90-year-old Irene Triplett died in North Carolina, having collected a pension of $73.13 each month. Cheerful, tobacco-chewing Irene, who had unspecified cognitive impairments, had lived in care homes since her mother's death in 1967.

Triplett's case was unusual, but not wildly so. When she was born, her mother Elida Hall was 34, but her father Mose Triplett was 83. Originally in the Confederate Army, Triplett had (conveniently) fallen ill before the Battle of Gettysburg, one of the most crucial of the entire Civil War, in which most of the men in his unit were killed, injured, or captured. Crucially for Irene's future, he then joined a Union regiment, entitling him to an army pension (the security this income provided may explain his appeal to his much younger second wife). As the dependent child of a veteran who had (ultimately) been on the winning side, Irene was entitled to a degree of government support.

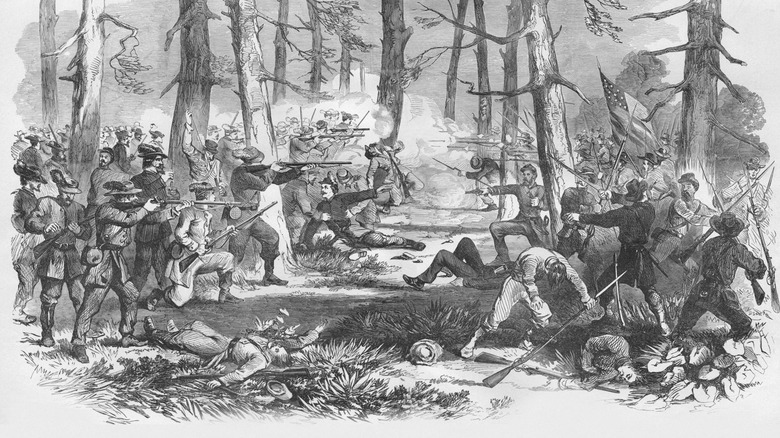

Why did the Confederacy invade neutral Kentucky?

Supposedly, Abraham Lincoln said early in the Civil War, "I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky." Kentucky was well placed to serve as an asset for either side in the developing war: its rich farmland was attractive enough, but most of its entire northern border was the Ohio River, a crucial transportation artery with long banks facing Ohio and Indiana on the other side. Confederate control or interference here would be enormous trouble for the Union. Conversely, the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers offered attractive invasion routes into the South in the event Kentucky stayed with the Union. Kentucky's loyalty was one of the most desirable prizes up for grabs early in the war, especially after the slaveholding state with important cultural and economic ties to the North attempted to declare itself neutral.

A neutral Kentucky unwilling to cooperate with Union war aims was much better for the South than an actively Unionist Kentucky, but the South absolutely biffed this opportunity. In April 1861, the Louisville Journal (via the Essential Civil War Curriculum) reported a senator from Georgia saying that "the border states would have to do all the fighting," allowing the remainder of the South to "undisturbed ... go about its business raising slaves and cotton." Border state Kentucky didn't like that attitude; they liked it even less when Southern sympathizers confiscated railroad equipment and the Confederate Congress banned the northward export of cotton.

The tipping point was the Confederate invasion of Kentucky, when they snagged the small city of Columbus, Kentucky, as part of a failed plan to take the port of Paducah. Suddenly, the Union's nagging to fight with them didn't seem so bad, and Kentucky ended its neutrality on September 18, 1861.

Why was the capital of Confederate Missouri in Texas?

There were officially eleven Confederate states, but the famous X-designed battle flag has thirteen stars, reflecting the hope that internally divided Kentucky and Missouri would ultimately wind up in the Southern fold. Both of these states had their share of Southern sympathizers but stayed in the Union despite the efforts of "Confederate" governments for each state. Kentucky's Confederate government claimed a capital at Bowling Green, which it lost to Union forces in early 1862. Confederate Missouri had a less intuitive idea and set up its capital in Marshall, a prosperous city ... in northeast Texas.

Marshall was an important manufacturing hub for the South and, after the fall of Vicksburg snipped the Confederacy in two, served as the capital of the isolated Confederate West, but it's nowhere near Missouri. Divided Missouri had attempted Kentucky-style neutrality and the Union had responded by strategically placing units around the state and solidifying control of all-important St. Louis, so the Confederacy never seriously had a chance to control the most important city in the state nor the capital at Jefferson City, located in the center of Missouri. Marshall's out-of-the-way location in northeastern Texas, hundreds of miles away from the Missouri border, did at least keep officials far from the fighting.

Why did Saxe-Coburg-Gotha recognize the Confederacy, alone among European countries?

An important part of the Union war effort was to keep outside powers, particularly strong European countries, from fully recognizing the Confederacy as an independent state with a legitimate government. Their (not irrational) concern was that manufacturing powers that depended on raw Southern cotton to feed their industry, especially Britain, would back the South to keep their warehouses full and their looms running. Aggressive Union diplomacy, the consistent Southern failure to notch convincing wins, European unease with backing a slaveholding power, and crises closer to home kept Europe mostly on the sidelines and the Confederacy without formal diplomatic relations ... with one exception.

That exception was the little duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, one of the constellation of small German states that existed when Germany had not yet congealed into a unified country. Saxe-Coburg-Gotha's main export was princes and princesses, most famously the Prince Albert who married Britain's Queen Victoria. It was not a financial or industrial power; since its territory wasn't contiguous, it wasn't even especially easy to find on a map.

Nevertheless, plucky little Saxe-Coburg-Gotha sent the only accredited diplomat to arrive in the Confederacy, with consul Ernst Raven arriving in Texas in 1861. Saxe-Coburg-Gotha soon joined the Confederacy in the roll call of countries that no longer exist: it was rolled up under the umbrella of the German Empire in 1871 and formally dissolved with the rest of Germany's hereditary monarchies in 1918, after defeat in World War I.

How did Judah Benjamin escape?

Judah Benjamin was one of the most colorful and controversial members of the Confederate government. Born into a Jewish family in the West Indies, he emigrated to New Orleans as a child and later built a successful career as a lawyer. In an 1834 case, he made legal arguments in a complex case involving the unattractive concept of slave insurance that contained ringing endorsements of the personhood of the enslaved. However, this didn't stop Benjamin from accepting two enslaved people as part of his wife's dowry and eventually becoming a plantation owner. Elected a senator for Louisiana in 1852, he later joined the Confederate government, serving as attorney general, Secretary of War, and Secretary of State in the years before the Confederate surrender at Appomattox.

When the Confederate government was finally crumbling, Benjamin knew it was time to scoot. Sometime in early May, with the war over but the Confederate government still scuttling through the ruined South, Benjamin broke off from the party containing Confederate president Jefferson Davis and moved through Florida; one account has him pretending to be French. The details of this escape are scanty and overgrown with legend, and since Benjamin never wrote his memoirs (and even burned his personal papers before his death), the story seems destined to remain obscure. Nevertheless, he was the only major figure in the Confederate government to successfully escape the imploding South. He ultimately made it to Havana and then to Britain, where he rebuilt a career as an attorney. After his death in 1884, he was buried in Paris' famed Pere Lachaise cemetery, originally under the pseudonym Philippe Benjamin.

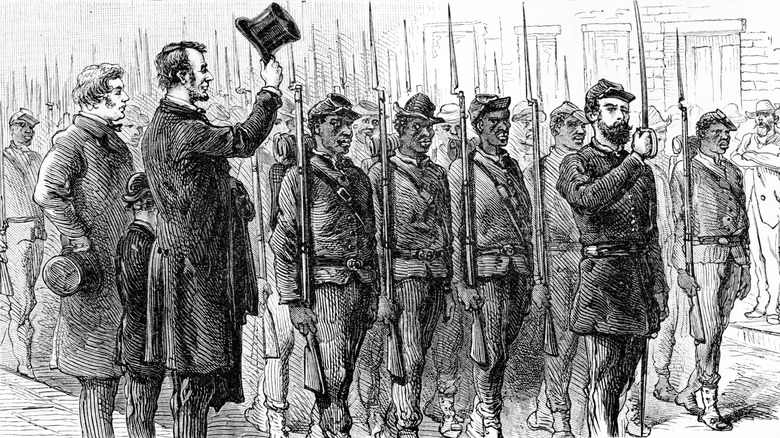

Was the Confederacy really trying to arm enslaved men?

During the Civil War, Black Americans, often freedmen who had been liberated by the Union Army, served with distinction in many theaters and battles ... under Union colors, it may be superfluous to say. Confederate law stated that only white men could fight for the South. Natives who participated did so as allies, not members of the Confederate army; enslaved Black Southerners were impressed into support roles, like cooks and transport workers, but were not armed and did not fight. But in early 1865, well past the point when most people thought the Confederate experiment was salvageable, one of the throw-spaghetti-at-the-Yankees-and-see-if-it-sticks ideas the dying South had was to arm enslaved men to fight for the almost-lost cause.

An act of the Confederate congress in March 1865 allowed for the "experimental" arming of enslaved men, and it went as badly as you might think. Arguments raged about whether the enslaved men should be freed for their service; the men who participated were suspected, probably not irrationally, of doing so out of a desire to escape to Union lines, and in general the Confederate establishment was so jittery about arming enslaved men that only small numbers of such men were ever organized to help defend Richmond. A few weeks later, the Confederacy was ended, and soon thereafter, there were no longer enslaved people in the United States to impress.

Where is the Confederate gold?

"Lost Confederate gold" is at the core of a number of local legends in the United States, sometimes with a grain of truth: two Baltimore boys found a cache of coins in 1934, and in 2023 a Civil War-era gold hoard was found in Kentucky. The Confederacy was under pressure during its entire existence, and so records are not always optimal; the chaos of the war meant that assets could well go missing as desperate or opportunistic people took opportunities; and individuals may have buried or concealed personal funds to hide them from whichever army they were worried about at the time.

A particular alleged jackpot is the remains of the Confederate treasury, which limped south through Virginia and the Carolinas with Jefferson Davis and the fleeing Confederate government after the fall of Richmond. Much of this money was dispersed to pay Confederate soldiers returning home, yet a quarter million dollars (in 1865 money, no less) was stolen by bandits from under the noses of a Union detachment hoping to capture it intact. Some was recovered, most was not. Optimistic treasure hunters might well hope that some of this money lies concealed and undiscovered somewhere in rural Georgia, but a more pessimistic view is that it was probably all spent long ago by hungry people in a ruined state.

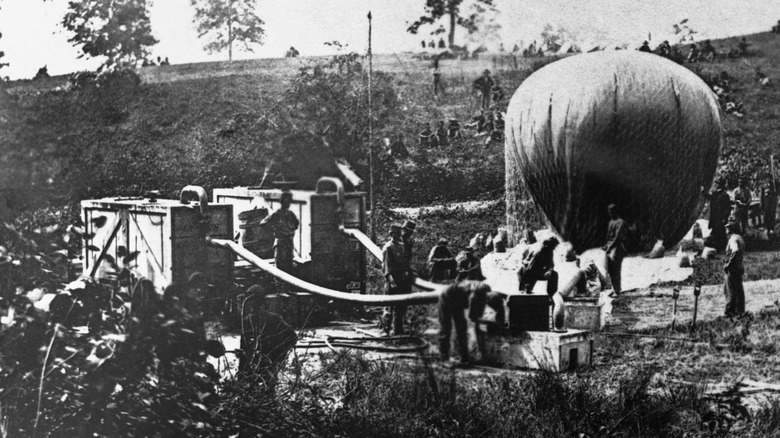

Why was the balloon corps disbanded?

The idea of hot air balloons as weapons of war may seem whimsical, as though a teddy bear might throw weaponized gumdrops down from them. But the playful, relatively impractical vehicles were used for aerial reconnaissance during early battles of the French Revolutionary Wars, possibly contributing to the important French victory at the Battle of Fleurus. Both Union and Confederate forces, optimistic about the military advantages a bird's-eye view could offer, fielded balloons early in the war. Inflated with gas from city supplies or from portable hydrogen generators, Civil War military balloons could carry one to five men, depending on the particular craft, and were both used to observe enemy movements and to help target allied artillery fire.

Both sides sent balloons up to spot the other's movements during the Seven Days Campaign, when the Confederates pushed back Union attempts to capture Richmond despite Union balloons having eyes on the city' downtown. But a little earlier in the war, Union general Fitz John Porter had an alarming experience when the observation balloon he had boarded came loose from its tether and drifted over Confederate lines. Potshots notwithstanding, Porter drifted back into Union-held territory and safely descended, going on to sketch the Confederate positions he had observed. The Union program was disbanded in 1863, despite its apparent usefulness; a fragmentary account exists of balloon use during the Siege of Petersburg in 1864. Confederate efforts petered out after one balloon fell prey to friendly fire and another was captured.