Warning Signs Everyone Ignored Before Infamous Events Happened

In the "Iliad," Cassandra is a Trojan princess with a cursed blessing of the type common in classical myth: she is a clairvoyant, with clear knowledge of future events, but she is fated to be disbelieved and discounted by those around her. When she says things like "let's not steal that man's wife" or "let's not let in that wooden horse of unclear provenance" or "listen, your wife has an axe," no one listens to her, generally much to their later (usually brief) chagrin. But sometimes, you don't need a cursed seeress to see that danger is right around the corner. Sometimes, all you have to do is pay attention to the extremely clear warning signs around you, and throughout history, this was sometimes exactly what didn't happen before disaster struck.

Unfortunately, the people receiving warnings aren't always able to respond, and the unwillingness of authorities to do so can lead to colossal loss of life, injury, and damage to property. From industrial accidents to wars to volcanic eruptions, here are some of the worst events to have their warning signs ignored.

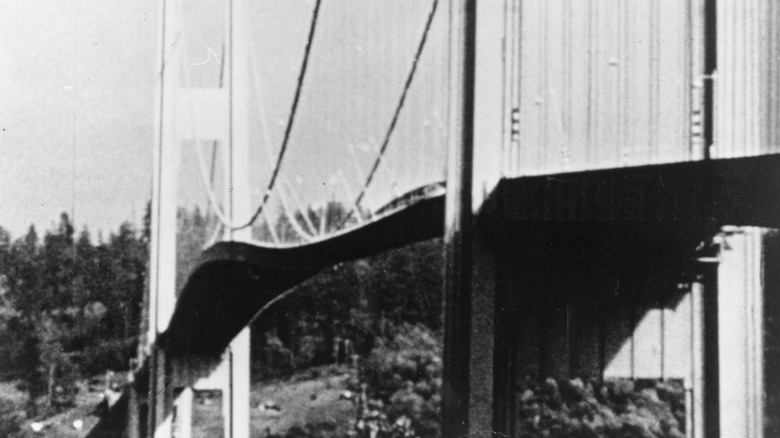

Tacoma Narrows Bridge

Bridges are traditionally associated with concepts like "reliability" and "connection." A bridge should not be exciting; a bridge should be solid and, above all, relatively still. Unfortunately for Tacoma-area commuters and a singularly unfortunate cocker spaniel, the original Tacoma Narrows Bridge, which spanned the waters of the Puget Sound, was a magnificently bad example of bridge construction. It opened on July 1, 1940, and quickly received the nickname "Galloping Gertie" because of the dramatic undulations that rocked the bridge when it was exposed to wind.

On November 7, 1940, winds of about 42 miles an hour (for reference, the threshold for a tropical storm is 39 mph) rocked Galloping Gertie so hard that the bridge flew apart in one of the worst structural engineering failures in American history. Authorities had managed to close the bridge in time, and so the only death was of a cocker spaniel abandoned in a car, though you might credibly ask why a galloping bridge was ever open in the first place.

The collapse was captured on tape, in part because engineers were filming the installation of supports intended to ease the gallop. A photographer from the Tacoma News Tribune, who had been on the bridge shortly before it fell and struggled to get away, was recorded as saying (via WSDOT), "I was bruised, black and blue from my hips to my feet the next day and for two weeks. I don't think anything more exciting has ever happened to me."

The Fall of Constantinople

By the mid-1400s, the once-proud Byzantine Empire, which had survived its Western Roman sister by nearly a thousand years, was teetering. Generations of territorial losses to neighbors, most recently the expansionist Ottoman Turks, left the empire holding only a chunk of modern Greece and the area immediately around Constantinople. Nicknamed "the City of the World's Desire," it was certainly the desire of the young and ambitious sultan Mehmed II, remembered by history as Mehmed the Conqueror.

Constantinople had withstood many, many sieges in the past thanks to its magnificent defensive walls, but this time Mehmed had upped his game by bringing massive cannons. He got ready to use them by making peace with Hungary and Venice (who might come to the Byzantines' aid), as well as building a fort called Throat-Cutter Castle to menace transports between the Black and Mediterranean Seas via the Bosphorus Strait. The cannons, not yet especially mobile, were moved from Edirne to outside the city, in full view of its inhabitants.

The Byzantine Emperor sent frantic messages for help, only to have Pope Nicholas V (a terrible human being despite his role as a religious leader) try to use it as an opportunity for political wrangling. Venice and Genoa sent a few boats and some troops, which were of little help. The city walls fell on May 29, 1453, leaving southeastern Europe open to Turkish armies for generations.

Yom Kippur War

In 1973, Israel's Arab neighbors were still smarting from its smashing victory in the 1967 Six-Day War, which saw it capture territory from Jordan, Egypt, and Syria, including the much-contested Old City of Jerusalem. Egypt and Israel had continued a low-intensity air war until 1970, and as soon as it was ended (under U.S. pressure) the Egyptians moved Soviet-made anti-aircraft weapons to the Suez Canal, which was then the line of control between the countries. Israel did not immediately respond, apparently due to an incorrect but apparently widespread thought that the 1967 victory had convinced Egypt, Syria, and their allies that they would lose future direct confrontations.

That idea continued even after Egyptian president Anwar Sadat's threats of war in 1971, 1972, and third-time-unlucky 1973. This false-alarm strategy worked, and the Israelis were surprised when the Egyptian preparations they had seen in the summer and autumn of 1973 turned out to be actual preparations for war.

That war began on October 6, 1973, the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur (and during Islam's Ramadan). The resulting Yom Kippur War lasted three bloody weeks and ended in an effective stalemate, with little territory changing hands immediately. The prospect of indefinite conflict led Israel and Egypt to negotiate a peace agreement in 1979, but as even casual observers of the news will know, a stable peace in the region has yet to be realized.

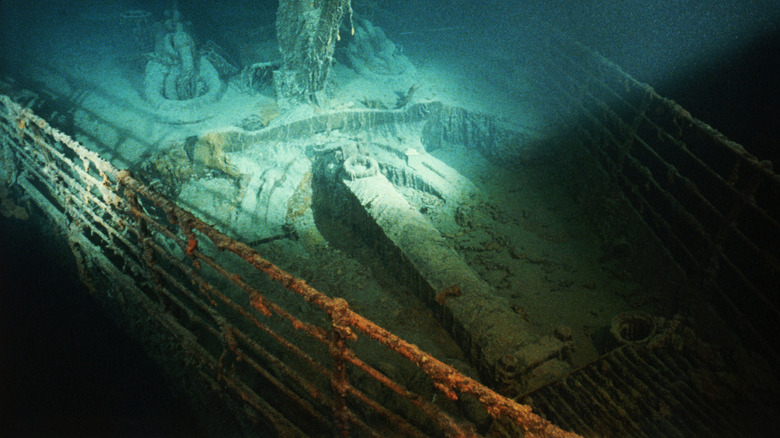

Sinking of the Titanic

On April 10, 1912, the huge and luxurious ship RMS Titanic left Southampton, United Kingdom, en route to New York. Famously, she never got there, instead wandering into a field of floating ice in the North Atlantic, hitting an iceberg, and breaking apart. Icebergs, even given their notoriously mostly-submerged nature, are big, white, and visible, and so reasonable observers might suspect that it would take some doing to miss one that's right in front of a ship. Sadly, in the case of the Titanic, they would be correct.

The Titanic sank on April 15, and just two days later the Chicago Examiner (via Encyclopedia Titanica) reported that a previous ship, La Bretagne, had received warnings from a Newfoundland lighthouse about dangerous amounts of ice in the water. The captain of La Bretagne assumed the Titanic must have received the all-directions radio warnings, as several other ships had. Captain Mace went on to report that, radio warnings aside, the clear skies had allowed him to see the icebergs and to direct his crew to avoid them.

Even more alarmingly, when the Californian transmitted to the Titanic to warn them that the Californian was dangerously surrounded by ice, telegraph operator Jack Philips told them not to interrupt him while he was forwarding messages from passengers. If all these warnings had been heeded, it's entirely possible the Titanic would have safely made it to New York.

Climate Change

Scientists, if not all politicians, agree that climate change is real, it's happening, and it's going to have some increasingly strange and unpleasant effects as our world warms. As this happens, we cannot credibly claim not to have been warned well in advance, because the alarm was sounded as far back as 1856. However, the researcher involved was an amateur (but accomplished) and a woman, and since what she was saying was inconvenient, her caution went unheeded.

During the 1850s, Eunice Foote, an American women's rights advocate and natural philosopher (as amateur scientists were then called), read some interesting geological findings. At the time, fossils were indicating a very different composition of plant life in the distant past, which suggested there had been more carbon dioxide in the Earth's atmosphere. Foote set up a simple experiment of glass cylinders filled with different gases and noted that the one containing carbon dioxide heated the enclosed thermometer more quickly than her others. Foote's work was presented by a male colleague at a conference in 1856, and short summaries of her work were published in 1856 and 1857, but concern about the rising levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere at large did not break through. Foote, who was a signatory to the women's rights petition at the first Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, might at least be pleased that American women did receive the vote ... eventually.

Hurricane Katrina

On September 9, 1965, Hurricane Betsy whipped ashore at the extreme southeastern tip of Louisiana, smashing the beach town of Grand Isle and flooding parts of New Orleans, with water reaching the roofs of some houses in the city's east. "Billion-Dollar Betsy" was the first storm to cause nine figures of damage to the United States; she also claimed 81 lives and drew attention to the fact that New Orleans — a bowl-shaped city mostly lying below sea level and surrounded by wetlands, lakes, and a large meander of the Mississippi River — was extremely vulnerable to a hurricane. This cultural powerhouse, shipping linchpin, and petroleum hub clearly needed protection, but slow and incomplete action was to later doom many of the city's residents and cultural treasures.

In 2003, a report in Civil Engineering Magazine noted that refurbished levees would be finished along the city's northern edge "in the next decade," with ones along the curving southern border probably needing a few more years. The city still didn't have them by August 29, 2005, when Hurricane Katrina sloshed ashore along a path eerily similar to Betsy's, pushing a storm surge into the city that overwhelmed many of the existing defenses. The flooding and subsequent governmental failure to manage the humanitarian crisis left an official toll of 1,833 dead and much of the city in ruins.

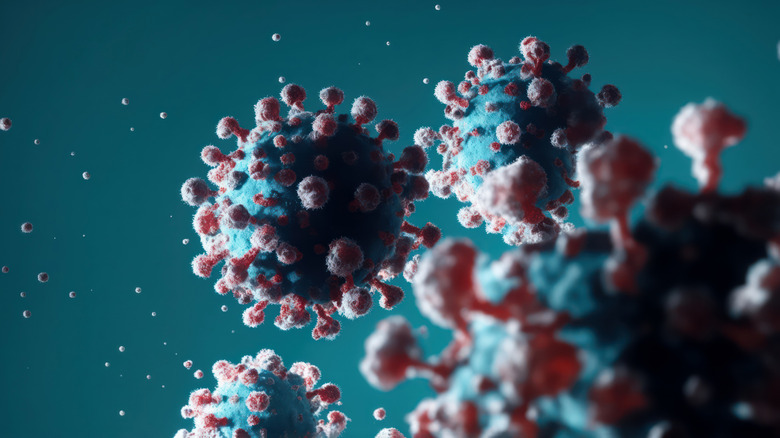

COVID-19

In late 2019, a new virus appeared in the city of Wuhan, China. By March 2020, entire countries were effectively shutting down, issuing stay-at-home orders of varying strictness and watching as COVID-19 spread anyway, sickening, disabling, and killing people worldwide. The state of emergency in the United States lasted over three years. Could any of this chaos have been prevented?

A report commissioned in 2021 by the World Health Organization found both national and international responses to the initial outbreak lacking. The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response argued, among other points, that China had reported the novel virus and its spread too late, that the WHO had subsequently reacted too slowly in declaring an international health emergency, and that the WHO had further dithered in waiting to advise travel restrictions. Furthermore, individual countries, especially the United States and those in Europe, had not responded forcefully until filling hospitals made the gravity of the situation unavoidably clear, effectively wasting the critical month of February 2020. The report included recommendations for avoiding a "repeat" in the case of another, similar epidemic; unfortunately, it may take another outbreak to determine whether these have been sufficiently enacted.

The Station Nightclub Fire

In 2003 a fire at a West Warwick, Rhode Island, nightclub called The Station, also known as the Great White fire after the headlining band, was among the worst nightclub fires on record, with 100 dead (including a member of Great White, guitarist Ty Longley) and many more injured. The blaze started the evening of February 20, when pyrotechnics — Great White was and is a hair metal band — were activated at the band's entrance, igniting the polyurethane foam that had been installed as soundproofing. As an added hazard, burning polyurethane releases the toxic gases hydrogen cyanide (of gas chamber infamy) and carbon monoxide. In under five minutes, the entire nightclub was ablaze.

Astonishingly, The Station had recently passed a fire inspection. On November 20, 2002, fire inspector Denis Larocque had cited the club for nine minor violations; these were addressed, and Larocque approved the upgrades during a follow-up visit on December 2. According to The Providence Journal, when questioned later, Larocque said he hadn't noticed the dangerous foam because he was "blinded by anger" about a badly installed door (which swung inwards, rather than a far-safer outward-swinging installation).

In a particularly bitter irony, the afternoon before the fire, the state fire marshal had publicly praised Rhode Island's fire safety codes, indicating that they made conflagrations and stampedes similar to a recent Chicago tragedy unlikely in the Ocean State.

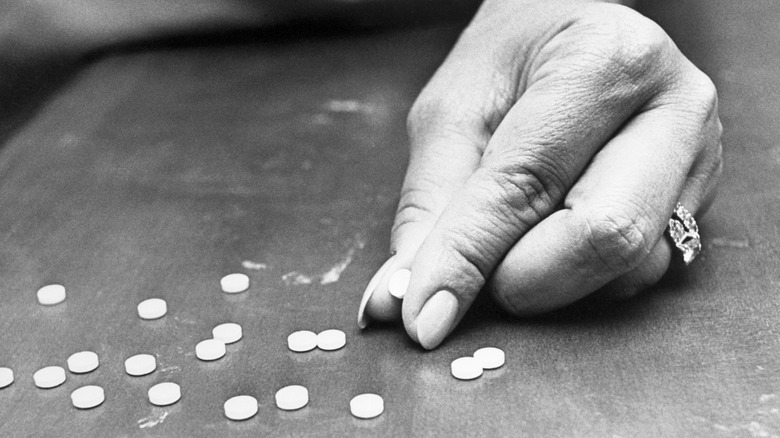

Thalidomide

In 1960, Canadian scientist Frances Kelsey was working for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and she found something she didn't like. She had been given a file for a drug, thalidomide, that was widely used in Europe, particularly Britain, to help pregnant women with insomnia and morning sickness. Kelsey, who had only been at the USDA a month but had previous experience testing drugs that could cross the placenta from mother to fetus, didn't think the application for approval was complete: it offered insufficient data about safety or efficacy. William S. Merrell Co. of Cincinnati, the drugmaker, nagged her; Kelsey stuck to her guns. By 1961, the first reports of side effects had come out: children born to mothers taking thalidomide were born with serious limb deformities, with either flipper-like structures or lacking them entirely.

U.S. mothers had dodged a bullet. Canada, which had received essentially the same application at about the same time as the one to which Kelsey objected, did not. Even after Britain and Germany pulled the drug from the market in late 1961, Canada dawdled for three more months before yanking thalidomide from its markets. Over 100 Canadians were ultimately born with thalidomide-related birth defects; an advocacy group now protects their interests. Thalidomide was ultimately approved for use in the United States — for leprosy.

Bhopal Disaster

Over a two-year span from fall 1982 to summer 1984, journalist Rajkumar Keswani wrote several articles warning of unsafe conditions at a chemical plant in Bhopal, a green lakeside city in central India. Keswani's sources included employees of the plant and a report on safety conditions commissioned in 1982 by the plant's owner, the American company Union Carbide. The journalist warned that the report found a number of concerning issues, including defective or simply missing equipment, as well as high employee turnover. Pressure gauges were broken, tanks had no indicators of how full they were, and sprinklers were simply absent. And as early as 1975, a bureaucrat had recommended the factory be moved away from the populous city.

The chemical plant wasn't moved, and on the night of December 2, 1984, Bhopal came to regret it. A huge cloud of methyl isocyanate (a chemical used in the manufacture of pesticides, polyurethane foam, and plastics), along with other chemicals, poured from the plant, instantly killing thousands. Eventually, over 20,000 people are estimated to have died from the toxic gas leak, and over half a million people were injured and left disabled in the world's worst industrial disaster in history.

Union Carbide settled out of court with the government of India (not with survivors directly) for a relatively paltry $470 million, later selling its Indian branch to Dow Chemical. For its part, Dow claims to have clean hands, as it did not operate the plant at the time. Meanwhile, survivor groups continue to advocate for accountability and redress.

Armero Lahar

In October 1985, Colombian geologist Marta Lucía Calvache Velasco and her colleagues made what should have been a startling report to the Colombian government: The Nevado del Ruiz volcano, located in the north of the country, was about to erupt. While the threat wasn't declared to be imminent, with months or years on the outside given as a likely timeline, precautions were strongly advised.

Unfortunately for most of the population of the nearby town of Armero, the Colombian government was distracted: the country's long-simmering civil war had again reached the capital, Bogota. Additionally, no real system existed to transmit warnings to local governments or residents who could act upon them, nor was the Colombian infrastructure able to consistently and effectively monitor the area for tremors that might indicate a large eruption.

The volcano did not wait for these matters to be resolved, and on November 13, 1985, the volcano awakened. Some ash had fallen on the town that evening, but both local religious leaders and the fire department had urged calm. Disastrously, the heat from the volcano was melting some of the glaciers that lay atop it, producing the conditions for an especially fast and dangerous form of landslide called a lahar. A massive lahar was funneled into a narrow riverbed, and the river burst its banks and buried Armero, killing some 25,000 of the 30,000 residents. This horror did, at least, lead to improvements in Colombia's disaster preparedness: a similar eruption less than 4 years later claimed no human lives thanks to improved detection and warning systems.

Aberfan Coal Tip Disaster

Mining produces waste, which might be evident: not everything you dig out of the ground will be what you want. Unfortunately for the mining town of Aberfan, Wales, one of the accepted means of disposing of such waste is to stack it in huge piles. By the fall of 1966, a "tip" (pile of mining waste) containing 300,000 cubic yards of debris and rising 111 feet stood outside Aberfan. Most residents did not realize that it had been placed over a spring on porous rock, but did know that the rainy autumn had left the tip, and everything else, saturated. On the morning of October 21, this massive wet mound collapsed, sending a wave of watery debris into Aberfan and burying, among other buildings, an elementary school. Tragically, 144 people died, 116 of them schoolchildren.

A tribunal found it all to have been avoidable. Their report noted that Aberfan regularly flooded, with the water visibly contaminated by coal waste. Many people had expressed concern to authorities about the tip, including members of the town council, local politicians, parents of students attending the destroyed school, and members of the public, including that a promised retaining wall had never materialized. Full responsibility was assigned to the National Coal Board, but charges were never brought against any individuals.

Challenger disaster

The night of January 27 to 28, 1986, was unusually cold for Central Florida, with the space shuttle launch pad of Cape Canaveral accumulating a thick layer of ice. Onlookers who braved the weather to watch the launch were horrified when, 73 seconds after liftoff, the Space Shuttle Challenger broke apart, killing all seven astronauts aboard in an explosion that would rain debris on the adjacent Atlantic Ocean for over an hour. The last transmission from the craft was a concise "uh-oh," hopefully implying that the astronauts didn't have time to understand their fate.

It turned out that the cold was the culprit. The low temperatures had caused rubber O-rings to become too brittle to successfully contain hot gases produced by the rocket fuel, and these had leaked out and damaged a fuel tank, which had then exploded as its contents mixed uncontrollably. A subsequent inquiry helmed by Richard Feynman, a noted physicist who made no attempt to conceal his anger, blamed NASA's broken safety reporting culture. The supplier who produced the rings had alerted NASA to the flaw as early as 1977, close to a decade before the lethal failure, and examples of the exact same part that had been damaged during flight had been discovered in 1981.

U.S. space shuttles were redesigned, and proof that someone had learned a lesson came in 1995. Alerted to damage to O-rings on the shuttle Endeavor, NASA delayed the launch for repairs, and the craft took off safely a month later.

1989 San Francisco Earthquake

Earthquakes cannot yet reliably be predicted, though advances in detectors have allowed scientists to come closer to developing a model that could warn people when a major tremor is coming (or at least probable). Shortly before the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake, which rattled the San Francisco Bay and claimed 63 lives, a seismologist named Jim Berkland thought he had its system figured out. By paying attention to the Earth's gravitational interactions with the sun and moon, which create tidal forces in land just as they do in the oceans, Berkland identified windows of time in which these forces might cause faults to give way. Additionally, he paid attention to the old superstitions that animals can sense danger, surmising that they can sense flux in the electromagnetic field.

In the fall of 1989, whales were beaching, dogs were running away, and Berkland told his fellow Californians to be on the lookout between October 14 and 21. The date was picked up by local media, but no real action was taken before the Loma Prieta quake hit on October 17. His annoyed superiors suspended him for two months for making predictions during working hours, and they may have had a point: Schools of dead sardines aside, Berkland's predictions of big quakes in 2009 and 2011 were flops.

2010 Haiti Earthquake

The world was horrified when a 7.0-magnitude earthquake smashed Haiti on January 12, 2010. Reliable estimates of the dead were and are hard to come by, as troubled Haiti was still recovering from serious tropical storm damage in 2008, but a million people were left homeless in a country of 9 million, and official estimates by the Haitian government count up to 300,000 killed. Some geophysicists felt that the devastation could have been mitigated had Haitian authorities acted on information they'd received several years earlier, indicating that one of the fault lines on which Haiti lies was due for a major quake.

The Enriquillo fault that runs under Haiti had been stretched to the point of snapping soon, which worried scientists. Nevertheless, had authorities acted to prepare the country for a major quake, Haiti would have been in a much better position to weather the tremor that materialized. With no building codes for earthquake resilience, buildings nationwide fell and killed or trapped the people inside, and with no stockpile of disaster supplies, the survivors faced hunger and exposure as international relief efforts were organized. Meanwhile, current models predict that the fault system underlying Haiti and the Dominican Republic remains active, and that the countries should prepare themselves for more quakes.

Fukushima Daiichi

On March 11, 2011, a powerful earthquake shook Japan so hard that the entire country was moved several meters to the east. Remarkably, the Great East Japan Earthquake didn't damage a collection of nuclear power plants on Japan's Eastern coast directly — but the gigantic tsunami it triggered did by swamping an inadequate seawall and flooding the Fukushima Daiichi complex. This inundation cut off power to the plant, damaged cooling systems, and cut road access. With control mechanisms offline, three reactors melted down, causing no direct deaths but forcing the evacuations of 150,000 people and requiring a years-long remediation effort.

During hearings in 2012, Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), which had initially tried to shift blame to Japan's prime minister and had claimed no one could have predicted a tsunami and earthquake that size in (checks notes) Japan, admitted fault. Fearing lawsuits, expense, and a perception of nuclear power as unsafe, TEPCO had ignored its own scientists' recommendations for improved disaster resilience that would have met international standards. TEPCO also had not trained its staff in emergency management, instead merely carrying out half-hearted drills. The Japanese parliament's investigatory panel went so far as to describe the disaster as "manmade", per The Guardian, citing flaccid regulation and a cultural preference for harmony over making tough changes, also noting that the risk of a tsunami creating a meltdown had been brought up as early as 2006. All that together makes it clear that we could have avoided the Fukushima Nuclear Plant Disaster.

Australia Black Saturday fires

By February 7, 2009, much of Victoria, a state in Southeastern Australia, was effectively kindling. The country had endured years of drought and was sweltering through a heat wave that had produced some of the hottest ever recorded temperatures in the state. On February 6, the state's head of government warned that the following day was expected to bring the worst conditions for brushfires in Victoria's history, with high temperatures and wind expected.

On February 7, powerful winds heated and dried by their passage over arid central Australia whipped into Victoria and brought down power lines, whose sparks ignited the plentiful dry brush. By nightfall, over 400 separate fires burned across Victoria, with some sending flames a hundred feet into the air. 2,000 houses, 173 people, and as many as a million animals were claimed by the cataclysmic fires, which took weeks to bring under control.

Reviews after the fire showed that, despite governmental warnings, a number of people in the affected areas had not realized that they were at risk, and that many residents of the damaged towns Bendigo and Horsham had not considered evacuation strategies. Additionally, many people misunderstood warnings as meaning they should be paying attention — not that they should get out.

1953 Tangiwai Lahar

A lahar is a particular kind of landslide-flood hybrid event. Eruption, unusually high rainfall, or another trigger will cause a slide of water, rock, and earth down the slope of a volcano, where it can be channeled into a riverbed and intensified by the tight passage. Their downhill trajectories also allow them to grow, presenting downhill or downstream communities with the snowballing mass of rapidly moving slurry.

Between the beginning of European records in 1840 and the holiday season of 1953, lahars fed by Mount Ruapehu, New Zealand's most active volcano, had barreled down the Whangaehu River at least four times. The railway bridge over the Whangaehu at the town of Tangiwai had been built in 1908 and survived the most recent event, in 1925, and New Zealand Railways had not put any disaster plan or warning system in place after this close call.

The bridge's reprieve would end on Christmas Eve, 1953. A torrent of freezing cold sludge, contaminated with sulfur from the volcano, smashed the bridge right as an express train from Wellington to Auckland approached. The train braked, but half of it fell into the stinking, rushing waters as several carriages in the back managed to remain on the intact remainder of the span. One hundred and fifty one people died, but since the first-class carriages were in the back, away from the noisy, smoky locomotive, all but one first-class passenger survived.

1980 Mount St. Helens eruption

Over the course of a few weeks in the spring of 1980, Mount St. Helens in Washington state began to bulge — never a reassuring sign for a volcano. A dome-like abscess of magma ominously distended the mountain's north flank, making scientists queasy about what would happen should the growing bubble pop. Steam and ash had belched from the volcano for a few weeks as the mound grew, but after this, the activity seemed to calm ... until mid-May. An earthquake shuddered across the mountain on May 12, and then on May 18, the whole north side of Mount St. Helens blew out in a blast that left a hole over two miles across and claimed 57 lives.

Many lives were saved by jittery researchers who had pestered local authorities to restrict access to the mountain and order evacuations. One of these scientists, David Johnston, was the first to report the eruption over the radio mere seconds before he was swept away. Some area residents had angrily protested the restrictions around the clearly percolating volcano, arguing that closing the space was an economic strain on area commerce; one of these was a "local character" named Harry R. Truman who had enjoyed giving defiantly crotchety interviews to the news about his plans to stay. When the fateful day came, some of those killed had refused to evacuate, while others were simply too close to a disaster that was bigger than anyone had predicted.

Above-ground nuclear testing

Between the first explosion of an atomic weapon, the Trinity Test in 1945 in New Mexico, and 1980, over 500 nuclear weapons were detonated in the Earth's atmosphere, 215 by the United States. Scientists and military planners knew that radiation from these tests was potentially dangerous, but they prioritized weapons development over public health. The real nuclear hazards of nuclear detonation had been proven, in the grimmest way possible, by the many people who died weeks and months after the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, but this did not dissuade U.S. decision-makers. Information about potential dangers was kept secret by the United States government for decades, even after the U.S. stopped above-ground testing in 1963.

Radioactive atmospheric fallout in the first decades of American nuclear testing may have killed hundreds of thousands of Americans. Many of the people exposed to radiation had the poor fortune to live near (and downwind from) the testing grounds, but new research indicates that people farther away were exposed through milk. One of the waste products generated by nuclear testing is a radioactive form of iodine, and if cows eat grass contaminated with it, they can secrete the radioactive iodine into their milk. Additional cancers among Americans who loved ice cream or lived in the desert likely killed more people than the actual attacks on Japan, per American Scientist.

The Aral Sea

There used to be a large and fertile sea in the middle of Central Asia, but it's gone now. The Aral Sea died because the Soviet Union thought it could bend the terrain of its captive republics to its will, diverting more and more water from the rivers that fed the landlocked body of water for harebrained agricultural development projects like "rice paddies in the desert" and "cotton farming in the desert." As more and more water was diverted, the Aral shrank. As early as 1964, observers could see that the situation wouldn't end happily, but the Soviet bureaucracy could not be bothered to change course.

Today, the Aral Sea's former footprint is littered with abandoned watercraft that lie where their owners gave up on chasing the retreating shoreline. Renamed the Aralkum Desert, the former seabed is no longer an oasis for migrating birds and an economic asset for the area's people. Instead, the dust, contaminated with pesticide runoff and whatever else the Soviets dumped, blows over the neighboring population and poisons the people who remained, who suffer from colossal rates of birth defects, anemia, and other ailments. The surrounding area is no longer productive, as the leftover salt the water left behind has drifted and affected the land's fertility. Meanwhile, the crisis threatens to repeat itself elsewhere: overuse of water in Utah is causing the Great Salt Lake to shrink and reveal the arsenic underneath.

The July Crisis

During the 18th century, European powers moved between alliances so consistently that the whole process was regularly compared to ballroom dancing, but the music was over by 1914. Europe had congealed into two opposing camps, and it wouldn't take much to pit them against each other on a battlefield.

Germany and Austria-Hungary locked arms in the middle of Europe. Britain was unnerved by Germany's growing navy, so it buddied up with France, still angry about losing territory to Germany in 1871. They allied with Russia to get the Germans and Austrians in a pincer. Russia remained interested in the safety of the Orthodox countries like Serbia that had recently become independent from Ottoman Turkey, which Germany was courting as an ally. Italy was allied with Austria-Hungary and Germany on paper, but lusted after some of Austria-Hungary's Western provinces.

If this sounds tense to the point of danger, that's because it was, and Europe narrowly missed major wars more than once during the early 20th century. So when a Serbian nationalist shot the heir to the Austrian throne for complicated reasons involving, as usual, Bosnia, everyone was on the edge of their seat. Austria-Hungary invaded Serbia, so to protect the Serbs, Russia declared war on Austria-Hungary. Germany fought Russia because it had guaranteed its help to Austria-Hungary. France and Britain had promised not to let Russia fight alone. And before you know it, here's World War I, exactly as many had foreseen but few had really wanted.

2017 Grenfell Tower fire

The fire that consumed the Grenfell Tower apartment building and killed 72 people in North Kensington, London, on June 14, 2017, was exacerbated by a number of factors. The responding firefighters fought hard against the blaze, but were insufficiently trained. Emergency services operators were given faulty guidance to pass on to frightened tenants. Elderly and disabled residents had been given no advice or instructions on how to respond to an emergency like the fire.

Worst of all, though, was the cladding. The building had been retrofitted with plastic and aluminum panels, ostensibly as insulation but possibly for aesthetics. Subsequent inquiries revealed that not only did this type of cladding not meet English building standards, but it had failed fire safety tests a jaw-dropping 12 separate times before the fire. An executive of the company that made the cladding had even pointed out how flammable it was in 2007, though this was in the context of potential brand damage if a fire killed 60 or 70 people (his estimate). Similar cladding had even been involved in fires in the United Arab Emirates in 2012 and 2013, though these fires led to no deaths.

Residents of Grenfell had complained about their landlord repeatedly, with fire safety among their stated concerns. Prophetically, a tenant advocacy group had predicted in 2016 that it would take a disaster for them to get any redress.

Sampoong Department Store collapse

The Sampoong Department Store collapse on June 29, 1995, in Seoul, South Korea, was one of the deadliest building collapses in modern history, killing over 500 and injuring nearly a thousand more. The bright pink store had been built on a former landfill during a loosely regulated building boom in South Korea, and its collapse forced the closure and demolition of a number of other buildings that had mushroomed up under similarly insufficient oversight.

Property developer Lee Joon had a foolproof plan for handling concerns from his contractors: He fired those who complained. By 1995, the building was low on support towers, which had been swapped out for escalators, and was fatally top-heavy, with a pool and restaurants on a later-added top floor and heavy air conditioning tanks on the roof. The tanks were too heavy and had been scooted across the roof, which had caused visible structural damage.

On the deadly day, cracks began appearing in the upper floors, so management simply closed them off and allowed shoppers to remain in parts of the building that were not visibly sagging. By the time they finally gave the order to evacuate, shoppers had mere minutes to flee, and it was not enough for many. Hundreds of survivors required rescue, with the last living victims — the unluckiest of the lucky — waiting under rubble for 17 days. After his trial, Joon received a relatively light seven-and-a-half-year prison term: less than six days per fatality.