Lies People Believe About Typhoid Mary

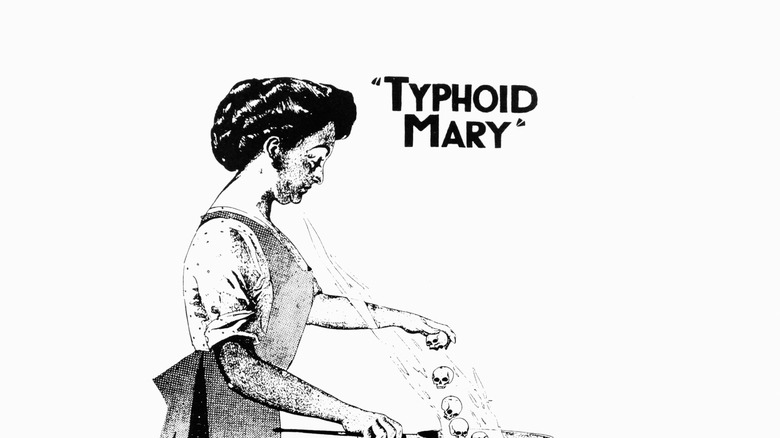

The story of Typhoid Mary has certainly gotten a bad historical rap. Even those who don't know any specifics about her recognize the name and the doom associated with it. As early as 1909, cartoons showed up about Mary in print, like one illustration in New York American showing her cracking tiny skulls into a pan like eggs. In the drawing, she's also breathing pestilence like a stream of fire or oil. The message is clear: Mary spreads plague and death.

Two years earlier, in 1907, sanitary engineer and amateur detective George Sober had tracked Mary around New York while investigating claims that typhoid could be traced back to freshwater. Sober had come across Mary, who displayed some symptoms of Typhoid fever, and he tracked her activities. Born Mary Mallon and having emigrated to the United States from Ireland, she cooked for various families to make a living. Sober discovered that members of seven of eight of those families had come down with Typhoid, equaling 22 people total. To make a long story short, Mary was eventually apprehended in 1907, tested and found positive for Typhoid, quarantined for three years, released in 1910, infected more people, and got confined again from 1915 until she died in 1938.

In the decades since then, Mary's story has grown to become something of a legend. Attempts have also been made to inject her tale with modern sociopolitical preoccupations and paint her as a nobly suffering victim of the mighty and powerful. This is an exaggeration. That being said, many aspects of her tale are commonly misunderstood or have gotten distorted over time.

Lie 1: Mary was the primary cause of Typhoid outbreak

Fans of zombie flicks or pathogenic apocalypse films know the deal by now: There's an outbreak of some plague, patient zero comes down with bleeding eyes or something, the pathogen spreads against the backdrop of an increasingly chaotic cityscape, survivors stick nails into baseball bats and fight against the necrotized mass of teeth-gnashing undead, and, uh ... What are we talking about? Ah yes, Typhoid Mary. But we made our point: Mary was not patient zero of some humanity-wiping end-of-days pandemic.

Typhoid fever has been with humanity at least since it wiped out one-third of the population of ancient Athens around 430 B.C.E. — or at least that's when it was first recorded. It's cropped up now and again across time, causing symptoms that sound like a bog-standard cold — headache, cough, fatigue, etc. — but involve an ever-increasing fever. Notably, there was a Typhoid outbreak in Jamestown, Virginia from 1607 to 1624 that killed over 6,000 people. In the U.S. Civil War from 1861 to 1865, about 80,000 troops died of a combination of Typhoid and dysentery.

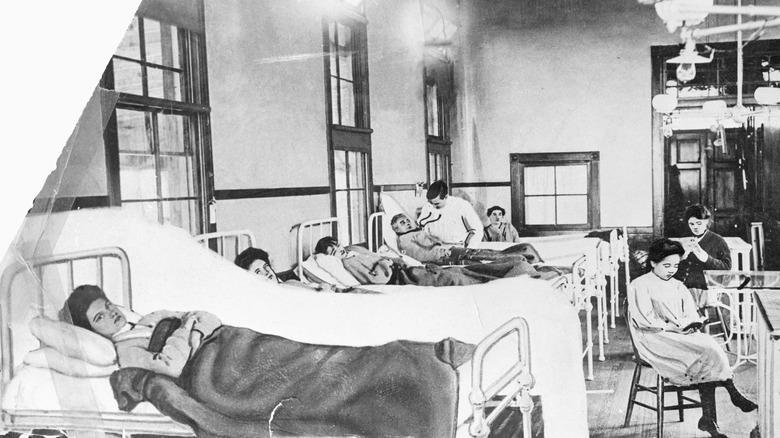

In 1907, the year that Typhoid Mary was caught, about 3,000 people came down with Typhoid fever in New York. Mary was definitely one vector (carrier) for the outbreak, but that's all that can be said for certain. Only four years later, in 1911, humans developed immunization against the bacteria that causes Typhoid fever — Salmonella typhi. Still, there was no antibiotic treatment for it until 1948.

Lie 2: Mary killed a lot of people

Related to our previous point: Typhoid Mary wasn't responsible for swaths of deaths across New York in 1907 or any other year. Of course, it must have been scary to see neighbors and family members fall prey to some illness that didn't have a clear cause (more on that later). But in the end, we can trace 51 cases of Typhoid fever and three deaths directly to Mary. Then again, once the public caught wind of her, she adopted aliases to maintain employment, like Mary Brown. So the actual number of illnesses and deaths that she caused could be higher.

1907 was the final year of a longer rash of Typhoid in New York City going back to 1898. That nine-year period saw 635 people die from Typhoid fever, a number that's high but still vastly lower than previous centuries because of improved sanitation, new medical practices, and knowledge of infectious diseases. That being said, densely-packed early-20th-century New York City was a case study in waste management, water contamination, food safety, etc. Typhoid fever was ultimately a big reason why cleanliness and hygienic practices improved, which reveals the true origins of the disease: Fecal matter in water.

Mary had lived and worked in New York since 1883. It's not clear when she got infected with Salmonella typhi. But it stands to reason that it must have been shortly before the narrow August-to-September window when the families she cooked for started coming down with symptoms of Typhoid fever.

Lie 3: Mary was obviously sick

Now we can get to an obvious question: Why did Typhoid Mary continue to work at families' houses while sick? Simple: It wasn't clear that she caused the illnesses. Per a 2013 study published in the Annals of Gastroenterology, she only presented a "moderate form" of Typhoid symptoms. It was George Sober, the sanitary engineer and amateur detective who tracked Mary, who suspected that she was the common link between the families who'd come down with Typhoid fever.

When questioned about whether or not she'd ever been sick with Typhoid fever, Mary said that she'd only ever experienced a "mild flu-like episode" at some point, per 1996's "Typhoid Mary: Captive to the Public's Health." She wasn't completely asymptotic, so she exhibited some symptoms while she carried the disease. Rather, she was just the first strangely lucky-but-unlucky person who exhibited a mild immune response to the Salmonella typhi bacteria.

Nonetheless, when Sober finally got the New York police to help him track Mary down and bring her in for testing in 1907, he got the confirmation he needed. She evaded the police for five hours before ultimately giving them a stool sample that tested positive for Salmonella typhi. Mary was quarantined, as had been done with the sick for millennia. During her three years of confinement, she sued the New York health department, failed, and was ultimately released in 1910 on the condition that she not return to her former line of work. She didn't comply. Instead, she took on an alias — Mary Brown — and went to cook for Sloane Maternity in Manhattan.

Lie 4: Mary intentionally infected people

Now we get to the sticking point that transforms Typhoid Mary from a hapless carrier of disease into something closer to the villain portrayed in that 1909 pestilence-breathing illustration that we mentioned earlier. That is: Why did Mary go back to work as a cook when she knew that she was cause of illness and death amongst families? Was it sheer obstinance? Was it disbelief in the realities of germ pathology? Did she just need money and have no other recourse? Two of the three deaths concretely attributed to Mary happened after her 1910 release from quarantine, when she swore to not return to her former line of work.

I's possible to concoct a story that paints Mary as a vengeful poisoner taking retribution for her three years of involuntary quarantine. It's also possible to take the condescending route and portray her as someone who somehow didn't realize she was responsible for her own actions — hence the continued fascination with her story. While we'll never know for certain what was going on in Mary's head, it's more plausible to think that she might have suspected that she was spreading Typhoid before being apprehended by police and George Sober, but wasn't going around intentionally infecting people.

Then again, we can always blame Mary for not washing her hands properly before handling food for a family. That's the most likely reason that she spread Typhoid fever around, particularly because of her love for a certain peach ice cream dessert that she often made. After all, cold temperatures don't kill the Salmonella typhi bacteria.

Lie 5: Mary spread Typhoid for a long time

Given the magnitude of Typhoid Mary's legend, you'd be forgiven for thinking that she was prowling the kitchens of New York City spreading plague and death for decades. While we know that she lived in the United States since arriving there in either 1883 or 1884, it's not clear exactly how long she worked as a domestic servant cooking for families. She likely contracted Typhoid fever not too long before she was apprehended in 1907 because instances of the disease connected to her suddenly appeared that year. Then, after being released from quarantine in 1910, she continued to work until 1915. But according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Typhoid bacteria persist in the body past 12 months in only 1% to 4% of people. Either Mary was in that small percentage or she got Typhoid again before infecting more people, post-quarantine, at Sloane Maternity under the alias "Mary Brown."

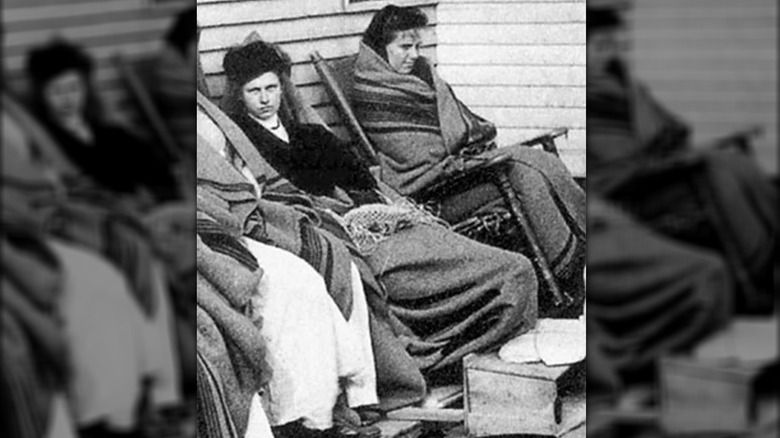

In other words, Mary didn't spend a significant portion of her life spreading Typhoid fever. She was in her late 30s when she infected people in 1907, and she lived the last 23 years of her life in quarantine at Riverside Hospital until she died in 1938. For the final six of those, she was paralyzed after experiencing a stroke. Only a short window of time accounted for her transformation into "Typhoid Mary," as the public dubbed her. But it only takes one brief moment of infamy to define a life, and that's probably how folks will continue to remember Mary.

Still interested? There are many facts about Typhoid Fever the average person doesn't know.