The Worst Punishments Humans Ever Created

Did you know that the iron maiden, at least as we've often imagined it, probably didn't exist? We've all seen that upright sarcophagus full of long spikes and imagined the horror medieval victims must have felt as it closed. Surprisingly, there's no evidence to suggest the medieval era ever used the iron maiden widely. The earliest and most popular account of its effects comes from Johann Philipp Siebenkees, a German philosopher writing in the 1700s. Since then, it's remained a fixture of torture museums and medieval exhibits around the world. The popularity of the iron maiden, in spite of its apparent ahistoricity, speaks to our fascination with old-fashioned torture methods.

Since the first introduction of the iron maiden, its goal has been to evoke dark daydreams of a bygone era. It invites a viewer to imagine the horrible things people used to do to each other, subtly encouraging them to see the modern era as comparatively humane. As a culture, we love looking at the cruelties of the olden days, shaking our heads, and proclaiming ourselves far better than our ancestors. However, the obsession with torment and retribution hasn't gone anywhere, and keeping it in the past only adds a faux scholarship to its grim popularity. Over the generations of human development, we've brought some truly brutal punishments all the way from imagination to execution.

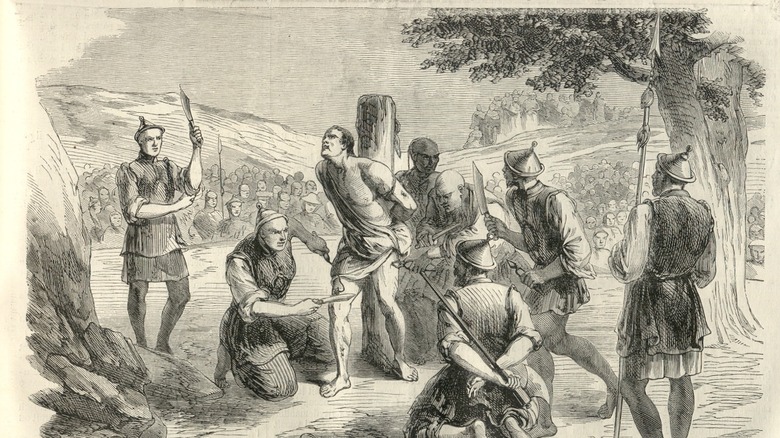

Breaking on the wheel

Some torture methods remain in the cultural consciousness for their elaborateness, but others are so simple that they become unforgettable. The breaking wheel is a very straightforward concept with several cultural alterations, but its public nature, brutality, and associations with well-known narratives make it iconic. Victims were bound by their limbs to a large wooden wheel. An executioner would then repeatedly strike them with a massive hammer or iron rod, breaking each of their limbs. The punishment would often end with a death blow to the face or chest after the executioner had had their fill of torture. As a form of capital punishment, the breaking wheel was usually reserved for murderers and traitors.

The biggest narrative association with the breaking wheel comes from the tale of St. Catherine of Alexandria. As a martyr, St. Catherine prepared to be executed for her faith. Her initial sentence was to be broken upon the wheel, but the wooden structure allegedly fell apart as she touched it. She was beheaded instead, keeping her off of the list of the most gruesome deaths of saints.

Many criminals were not so lucky. Like most execution methods of the era, the wheel was a public display that allowed locals to watch. The breaking wheel was primarily used in the Roman Empire and in the Middle Ages in France and Germany, but a 2019 study puts forth strong evidence for at least one example in Milan, Italy.

Impalement

Vlad III was the "voivode," or prince, of Wallachia in what is now Romania several times during the 15th century. He was known by two sobriquets: "Dracula," which marked him as the heir to his father Vlad II Dracul, and "Țepeș," which literally means "impaler." He got the latter nickname for his favorite method of executing his enemies. Vlad III probably killed around 80,000 people, at least 20,000 of them via impalement. Victims would have a wooden or metal spire of some width inserted into their bodies. Some were impaled horizontally, with the spike piercing their chest and exiting through their back, while others were impaled vertically. It's said that Vlad once dined in a forest full of impaled corpses.

While Vlad was unquestionably the most iconic practitioner of impalement, he was far from its only fan. In his "Voyages to the East Indies," Dutch traveler Johan Splinter Stavorinus described in detail an incident he saw in Batavia, the capital of the Dutch East Indies. Stavorinus saw a slave suffer impalement for murdering his master. He stated that the executioners made an incision near the victim's spine, then inserted the spike along his back to exit near his neck. The man reportedly died the following day, but Stavorinus claims that some victims survived their impalement for more than a week without access to food or drink.

Blood eagle

From the ninth to the 11th centuries, a subset of the Scandinavian population of Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish peoples took to the seas to raid and pillage most of Europe. These Vikings wrote their names in history, establishing a generations-long obsession with the perceived violence and brutality they unleashed in popular culture. One of the most questionable aspects of their supposed cruelty was an execution method called the blood eagle. The process involved shattering a victim's ribs, slicing open their back, and pulling their still-functioning lungs through the open cavity, creating an image somewhat like red wings. While the image is certainly evocative, it's also still historically debatable.

The blood eagle pops up in prose and poetry from the 11th century and beyond. While it may very well have happened, it likely wasn't as prevalent as some historically questionable TV shows like "Vikings" might suggest. An article in the University of Chicago Press Journals unpacks the torture method in both an anatomical and sociocultural context. The authors conclude that it would have been possible, though the victim would likely have died long before the ritual's intended conclusion. The text cites it as an act of revenge for the death of a family member, fitting into the larger trend of "bad deaths" in the culture.

Poena cullei

The ancient Romans invented and utilized several of the most innovative torture methods of all time. Many were so absurd, intricate, and impractical that even the modern-day dictators who rule several autocratic states wouldn't recreate them. Their oddest creation may have been poena cullei, or "the punishment of the sack," which could have been more of a threat than a widespread reality. According to Book 48 of "The Digest or Pandects," those guilty of the murder of a close family member would be savagely beaten with iron rods. The victim would then be "sewed up in a sack with a dog, a cock, a viper, and an ape" and tossed into the ocean.

Many historians debate the truth behind the punishment of the sack. Researchers charge 18th-century Germanic culture with the last known use of poena cullei, but the execution method was still very rare. Many debate whether it was used at all, pointing out the obvious logistical difficulties of keeping these animals in a bag together before delivering them to the sea. It does, however, fit comfortably into a larger trend of animal-based punishments that were common in ancient Rome.

Condemnation to the beast

The Romans became famous for making a spectacle out of their violent punishments. As anyone who has seen a movie set in ancient Rome knows, the Colosseum played host to just about every event a person could imagine. That's the real reason the Roman Colosseum was built. The classic image is a pair of warriors fighting to the death for the crowd's amusement, but the second most popular scenario sees a warrior face a massive beast in combat. This process, damnatio ad bestias, or "condemnation to the beasts," saw victims face off against wild dogs, bears, and lions. This was a form of capital punishment that drew a roaring crowd.

Seneca the Younger said of condemnation to the beasts, "In the morning men were thrown to lions and to bears, at midday to the spectators" (via BC Campus). As an eyewitness, he spoke to the fervor of the crowd, who would demand to see deaths in every event. By Cassius Dio's account, "Very few wild beasts perished, but a great many human beings did." Countless prisoners, rebellious slaves, and other convicts were torn apart by predators for the pleasure of an audience.

Lingchi

The phrase "death by a thousand cuts" is usually metaphorical in the modern day, but its literal interpretation was the height of capital punishment in traditional China. Lingchi means "slow slicing," and it was reserved for traitors, murderers, and alleged witches. Offenders would be tied to a pole or cross and slowly cut with a sharp knife. The number and location of those cuts would vary based on the executioner's whims. Some suffered eight slices in specific locations, but others experienced over 100 strokes of the blade. The executioner would generally prolong the offender's suffering as long as possible, dealing a fatal blow after ages of pain. A modified version of lingchi was employed in the horrific 1835 execution of Father Joseph Marchand, who would later be canonized for his suffering.

The alleged intent behind lingchi was to ruin the condemned person's spirit as well as their body. Mutilation on this level would carry over to the victim's soul, preventing them from returning in any recognizable form after death. China also used decapitation and strangulation as methods of capital punishment, reserving slow slicing for only the worst offenders. In some cases, the victim's severed head would be displayed as an example to other potential criminals. The practice of lingchi was banned by the Chinese government in 1905, along with several comparable methods of punishment.

Rats and coals

Modern popular culture has a way of grabbing and elevating historical modes of torture. Screenwriters and novelists discover one or two historical accounts of unhinged cruelty and turn them into widespread nightmares by reusing those ideas in something more ubiquitous. That has certainly been the fate of rat torture, a method of capital punishment that involves goading rodents into attacking and injuring victims. Some examples, most notably the Rats Dungeon in the Tower of London, involved leaving a victim in a chamber that would become populated with rats, some of whom may eventually bite the prisoner. A much worse version emerged in the Dutch Republic.

In John Lothrop Motley's "The Rise of the Dutch Republic," the author recounts the immense suffering of a father and son falsely accused of conspiring against a local ruler. The father passed quickly, but the son was burned, flayed, and stretched out on the rack. The torturers wielded a specially crafted ceramic bowl full of rats and placed hot coals into the other side. This forced the rats to claw, bite, and burrow through the victim's flesh to escape the heat. The rats, Motley claimed, "gnawed into the very bowels of the victim, in their agony to escape." This disgusting concept only appears in a few historical texts, but movies like "2 Fast 2 Furious" and "Terrifier 3" keep the idea alive.

Keelhauling

We've all heard a pirate in a movie threatening to "keelhaul" an enemy, but few of those works of fiction explored the meaning of that term. Keelhauling is, as the name somewhat suggests, the act of forcefully pulling a person along the keel of a ship via a long rope. A sailor who violated the surprisingly respectable pirate code of conduct would be tied up and tossed overboard then dragged against the underside of the vessel. The underside of almost any ship would be covered in barnacles, causing the keelhauling victim countless lacerations. After multiple rounds of keelhauling, many experienced broken ribs or drowned.

Historical accounts differ on the overall purpose of keelhauling. It's likely that some versions of the tactic were more lethal than others, but sources indicate that the original intention was not to kill the victim. In William Falconer's 1780 dictionary of naval terms, he specifies that many victims were given a brief pause between trips below the vessel. This allowed them to recover, but the process also rendered them insensible. While Falconer's account suggests a form of torture rather than one of execution, it also contends that keelhauling has "peculiar propriety in the depth of winter." Victims would approach the brink of death without dying if the sailors did things properly.

La parilla

No one in the modern era did torture quite like Augusto Pinochet. Pinochet launched a U.S.-backed military coup against the democratic socialist government of Chile in 1973, seizing power and immediately turning it against the citizenry. Labelling countless people enemies of the state, Pinochet's regime weaponized several of the worst imaginable actions against scared, helpless victims. One of Pinochet's favorite methods was a type of heightened electric shock commonly known as la parilla, or "the grill." Victims were tied to a metal bed frame with electrical wires attached, sending massive amounts of voltage through the person's body.

In a piece for The Guardian, torture survivor Sheila Cassidy described la parilla as "their favored aid to interrogation." Almost all testimonies from Pinochet's victims relate the stories of being repeatedly shocked, marking it as an extremely common part of their methods. Lelia Pérez, another young person who suffered Pinochet's torture for no apparent reason, told Amnesty International that her tormentors used a bunk bed. She stated, "There was another detainee on the top, and my partner was tied to the side," explaining that all three of them were tortured in turn for hours. She notes that the experience dehydrates its victims.

Necklacing

Being on the right side of history doesn't necessarily prevent a group from committing atrocities. Historically, any uprising against an unfair system has to resort to some terrible tactics, and there are few systems as unfair as apartheid in South Africa. The chief sin of the freedom fighters in South Africa was a method of public execution called necklacing. In the fight against the apartheid government, soldiers would typically use necklacing against disloyal party members and alleged spies. Victims had a tire full of fuel lowered onto their neck and set on fire, resulting in a horrible burning death.

The most famous case of necklacing was the televised murder of Maki Skosana. She is the first alleged victim, and her supposed crime was involvement in a hand grenade explosion that killed several children. Crimes like necklacing brought some negative attention to anti-apartheid fighters, but the African National Congress party mostly stayed quiet on the issue. Some senior members of the party that installed Nelson Mandela eventually admitted that they could've done more to prevent necklacing attacks. ANC leader Oliver Tambo disavowed necklacing but argued that the actions "originated from the extremes to which people were provoked by the unspeakable brutalities of the apartheid system" (via Time).

Crucifixion

Due to the tragic fate of one Jesus of Nazareth, crucifixion may be the most iconic method of execution ever devised by humanity. Jesus' experience was a fairly standard example, proving that it's horrible with or without the religious elements. Crucifixion was common in the ancient world, often wielded against those who opposed the religious or political order. Victims were whipped and forced to carry a large wooden crossbeam to their execution place. They'd then be lifted and bound to a towering stake, suspending them around 10 feet off the ground. They would gradually suffocate under the weight of their own bodies.

While Jesus was certainly the most notable victim of crucifixion, he was far from the only one. Researchers suggest that Assyrians and Babylonians introduced the concept, while the Persians used it much more frequently. Alexander the Great probably brought it to the Phoenicians, who introduced it to the Romans. The Romans conducted crucifixions for the next 500 years, but Emperor Constantine I outlawed the practice. Crucifixions are extremely rare in the modern day, though there are a couple of documented cases out of Syria and Yemen in the 2010s.

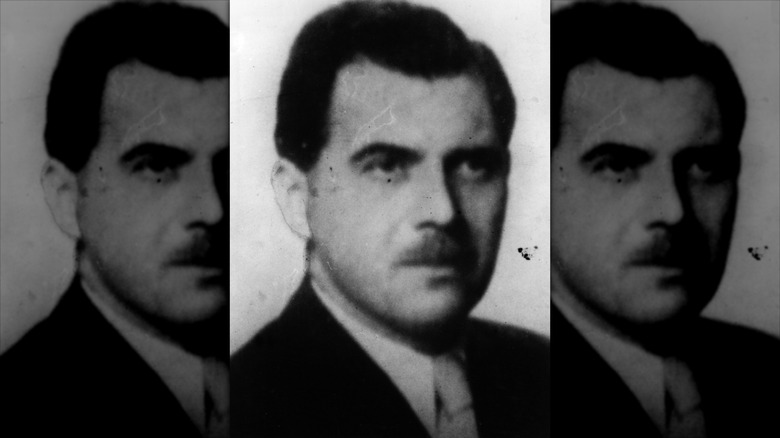

Human experimentation

Throughout history, many condemned people have been used for science against their will. This likely dates back thousands of years, probably beginning with multiple vivisections performed on unwilling prisoners between 300 and 200 B.C. Early scientists gained unique knowledge of the inner workings of human beings by butchering them on medical tables. For generations, doctors experimented on the recently executed to determine how long their brains remained active. In 1906, an American doctor exposed 24 inmates in the Philippines to an experimental vaccine that resulted in a plague outbreak, killing 13 of them.

In most cases, experimentation was more of a matter of convenience than actual punishment. Nazi Germany used the victims of its concentration camps, often accused of violating biased and absurd laws, as guinea pigs in horrific scientific tests. Nazi medical professionals such as Josef Mengele (pictured) are responsible for many of the most terrifying human experiments in history, including testing methods of mass sterilization and intentionally inflicting wounds on victims or infecting them with diseases to experiment with treatment methods. These experiments led to the creation of the Nuremberg Code governing human experimentation, which dictates that "the voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential."

Gibbeting

In common parlance, a gibbet is a synonym for gallows, the structure from which a noose hangs. The practice of gibbeting, or "hanging in chains," was similar to that of a more traditional hanging, but its intention was very different. The apparatus consists of a high wooden post, a short chain, and a cage that would contain the victim. Some art depicts this as a metal container that the victim would sit or crouch in, but many were fitted to the ribcage, allowing the body to swing freely. In most cases, gibbeting was a post-mortem punishment. The intent was to expose the rotting corpse to the world as a form of humiliation and deterrence. Unfortunately, some experienced the chains before their traditional execution.

The English were very fond of gibbeting, and while they mostly stuck to dead bodies in their homeland, they were far more cruel in their plantation colonies. English settlers hanged enslaved people in chains in Antigua, Jamaica, and even colonial America. These victims were typically involved in slave uprisings, prompting the English to use them as an example as they used murderers in their homeland. Anyone who was gibbeted live would languish for ages in full view of their people, slowly suffering and dying of deprivation and exposure. They would die and rot in major thoroughfares for the viewing benefit of others.