The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Jane Austen

The acclaimed novelist Jane Austen died two centuries ago, but her work as a storyteller and keen observer of human folly is just as relevant today as it was in Regency-era England. To the casual reader, it might seem that Austen — the author of such classics as Pride and Prejudice, Emma, and Sense and Sensibility — wrote primarily about the agony and ecstasy of young love. In truth, her sparkling and witty novels delve deeply into the injustices inherent in an economic system that forced women into a rigged and often cruel marriage market. For every perfectly happy Elizabeth Bennet and Anne Elliot, there is a Miss Bates and Mrs. Price, the latter ladies literary cautionary tales about what becomes of women should they a) fail to marry or b) marry the wrong man.

Austen experienced that first-hand. It's ironic that the writer of some of the most cherished love stories in the English language never found true love herself. And her writing was ridiculously undervalued during her lifetime. No one, of course, would have found fame funnier or more ripe for satire than she. It's too bad for her and the reading world that she never got a chance to write about it.

Her father's death ruined the family finances

Jane Austen was born December 16, 1775, the fifth child of George Austen, a gentleman curate, and Cassandra Leigh, the daughter of landed gentry. Her childhood was, according to this biography, an intellectually active one that saw her and her six siblings staging amateur theatricals and taking full advantage of their father's library. As a teenager, Jane wrote extensively, churning out funny sketches and stories for her family's amusement. And then, in 1805, after having moved the family to Bath, George Austen died. The surviving Austens were thrown into a world of uncertainty.

As The Daily Beast points out, George Austen's death meant that his two daughters, Jane and Cassandra, were stripped of their one means of "earning" a living — that of marrying well. Without a dowry from their dad, Jane and Cassandra were at a distinct disadvantage compared to other young women of their class. And because they were considered gentlewomen, they were not permitted to go outside of the home to work. Their only hope of achieving financial security was finding a suitable man to marry, a man who wasn't put off by their relative lack of worldly wealth.

In these dire circumstances and in the fact that British women of that time were not allowed to inherit property, Austen found her true subject: the incredible pressure women felt to marry up and the almost insurmountable difficulties they faced when they failed to do so.

Jane Austen's relationship with her mother was not always great

In her writing, Jane Austen made a study of bad mothers. There is the example of Mrs. Bennet of Pride and Prejudice, a shrill and hypochondriacal woman hellbent on marrying her daughters off to the highest bidder, and of Mrs. Morland of Northanger Abbey who is either too busy with housekeeping cares or too indolent to see that her daughter, Catherine, is suffering the pangs of first love. And let's not forget Mrs. Price of Mansfield Park, who carelessly sends her daughter, Fanny, to live with her rich sister, not stopping to consider for a moment that such a move might damn Fanny to a life of servitude and unhappiness.

With the exception of Mrs. Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility, the only really good mothers in Austen's fiction are the dead ones, a fact that has led a number of scholars to speculate on the relationship Austen had with her own mother, Cassandra (not to be confused with her sister of the same name). Some have concluded that the relationship was strained — that Mrs. Austen was a selfish hypochondriac and Jane an easy target of her wrath — and, according to The Guardian, Mrs. Austen wasn't shy about telling her daughter that she wasn't a fan of Mansfield Park. Her mother even went so far as to call Fanny Price, the novel's heroine, "insipid."

With mothers like that, who needs critics?

Jane Austen wrote about love but never found it herself

Jane Austen's novels always end — spoiler alert — with the girl getting the guy. Lizzie lands her Darcy, Elinor her Edward, Marianne her colonel, Anne her captain, Catherine her Henry, Fanny her Edmund, and Emma her Knightley. It's one of the sadder twists of fate (and Austen clearly loved a good plot twist) that the writer behind some of the most iconic love stories in English literature never starred in one herself.

Austen, a young woman of reportedly high spirits and strong dancing ability, did experience a couple flirtations in her life, the most significant with Tom Lefoy, a penniless Irish lawyer. According to the Independent, the romance ended because Lefoy had no choice but to marry money. Austen had none to offer. As this look at her life suggests, she fell in love again in her late twenties, this time with a minister whom she'd met while traveling from her childhood home to Bath. The man then died before they could reunite.

And in December 1802, Austen finally received a proposal of marriage from a wealthy friend's brother, Harris Bigg-Wither. At first, Austen accepted, perhaps because she knew it would lift her and her sister and mother out of poverty. The next day, though, she retracted her acceptance and fled the Bigg-Wither estate, not to mention her friends' anger, in shame and humiliation. So much for happily ever after.

Jane Austen was a nomad for a number of years

The death of George Austen, Jane's father, highlighted the inequity inherent in Regency-era England's economic system. Whereas Jane's older brothers, Edward, Henry, and James, were free to inherit George's fortune and pursue their own, Jane, her sister, Cassandra, and their mother became dependent on the kindness of others. As this piece from Oxford University shows, Jane's brothers did try to help out, but what they gave the women often wasn't enough, and the ladies were forced to move from place to place, often staying with friends and relatives. Having already composed first drafts of Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, and the novel that would later be known as Northanger Abbey, Jane's writing seems to have stalled during these nomadic years.

According to LitHub, Jane, Cassandra, and their mother lived in at least seven homes in four years, including three in Bath alone. In Southampton, a rough-and-tumble seaport, the three genteel ladies were almost certainly party to the violent and often unethical shenanigans of the Royal Navy and the ex-cons they recruited to fill their ships. The details of these years is fuzzy. Regardless, excitement did not seem to fuel Jane's work. It wasn't until the Austen women settled down in Chawton Cottage on the property of Jane's younger brother, Frank, in Hampshire that Jane found her voice again and began the serious work of revision and submitting her work for publication.

Jane Austen's brother, George, was institutionalized

The Austen family has long been described as creative, intelligent, and, above all, close-knit and affectionate, but such descriptions gloss over the fact that one of Jane's older brothers, George, was born disabled and was sent at a young age to live on a farm away from the family. According to this piece from the Jane Austen Society of North America, it's probable that neither Jane nor her parents nor her five other siblings ever bothered to visit George after he was sent away.

George, the second child of George and Cassandra Leigh Austen, seems to have been plagued with what in letters his parents call "fits," and his father hinted that he might have been "mentally deficient." And while George and Cassandra seemed understandably concerned about their son's welfare when he was a baby, after his removal from the family home at Steventon Rectory — most likely at the age of 13 — he got little attention from them or his siblings. Insult to injury, he did not appear in his mother's will. Nor does he get a mention in any of Jane's surviving letters.

He died at the age of 71. No one from his immediate family attended his funeral.

Jane Austen wasn't recognized for her writing until shortly before her death

Jane Austen started writing when she was a pre-teen, producing stories, plays, and poems mainly for the amusement of her large family. She even wrote a novel fragment parodying romantic literature, titled Love and Friendship, and, according to this overview of her early work, 26 other pieces that skewered everything from the history of England to a mother's love. These sketches, now referred to as Austen's "Juvenilia," were often broad and silly, but their wit and ambition hint at the sophisticated writer Jane would become in later life.

As talented and driven as she was, Austen's path to publication was a rocky one. One publisher sat so long on her manuscript for what would eventually become Northanger Abbey that Austen wrote to him to inquire about its fate, signing her letter with the initials "M.A.D." And, because she was a woman, when her books finally started to appear, they did so under the generic pseudonym, "A Lady." As this essay in the New York Times argues, Austen was most likely bowing to societal expectations when she decided to keep her name off her novels. Readers would expect a woman writer to canvas different territory than a man. Regardless, it wasn't until her late 30s that Austen was finally starting to get recognized for her genius, and by then she had little time left.

Jane Austen's death came too soon

Medical experts and scholars disagree about the cause of Jane Austen's death, with some saying it was due to Addison's Disease, others suggesting it was Hodkin's Lymphoma, and still others arguing that the culprit was breast cancer or, even accidental poisoning from a tainted water supply or medicine mix-up.

What they can all agree on is that Austen, a writer at the height of her creative powers, died too young. And, once she fell ill, she died relatively quickly — only 18 months after her first symptoms showed themselves. It's possible that she wrote off her symptoms because, as this article in Medical Humanities shows, Austen suffered from a number of ailments in her life, including chronic conjunctivitis and periodic infections. The fevers and face aches that characterized her last, fatal illness might not have struck her as different from other complaints she'd had as a young woman.

In the spring of 1817, her brother, Henry, and sister, Cassandra, took her to Winchester for treatment, but to no avail. She died that July.

Jane Austen's sister burned nearly all of her letters

Growing up, Jane's closest confidant was her sister, Cassandra. That did not change in later life. The two women were virtually inseparable. Even when apart, they were in constant communication, exchanging countless letters until Jane's death in 1817 at age 41. One might think such letters would provide a unique and intimate glimpse of Austen's world and the inspiration behind some of her most beloved novels. The unfortunate fact, though, is that, at age 70, Cassandra, worried about her often caustic sister's legacy, burned the bulk of the correspondence.

According to this article in the Independent, Cassandra's act of literary arson was her attempt to seal Jane's reputation as a sweet, shy, and unfailingly kind woman. Close readers and devoted fans — those who refer to themselves as "Janeites" — know, of course, that Jane Austen was not a saint. She was a witty satirist, a keen observer of human fallibility, a merciless writer of biting wit, and Cassandra's fateful decision to burn the letters that almost certainly displayed these qualities has cheated the reading world twice over. Not only are we deprived of the pleasure of seeing Jane Austen's world through her own clear and sometimes cynical eyes, but much of the truth of Jane Austen's life remains a mystery, a matter of tortured speculation.

Jane Austen died before she could complete her final novel

Jane Austen grew ill in 1816. That year, she was working on a new novel, Sanditon, a comic look at a new health fad known then as "taking the waters." The plot revolves around the efforts of the insufferable Mr. Parker to turn the seaside town of Sanditon into a magnet for the wealthy and ailing. In order to achieve his goal, he needs the help of Lady Denham, a reluctant benefactress and widow, not to mention scores of gullible tourists eager to spend their money on snake oil. So far, so ridiculous. Enter Charlotte Heywood, an intelligent young woman ripe for romance. All the ingredients of an Austen frolic are there. But then, 23,500 words in — in medias res, in other words — the book stops.

As this BBC piece points out, Austen abandoned the book just four months before her death. When her family discovered the unfinished manuscript, they were embarrassed by its broad humor. Worried it would damage Austen's by then sterling literary reputation, they refused to publish it in fragment form.

Not everyone is convinced of Sanditon's inferior quality, however. Some scholars have suggested that, had Austen been able to finish her novel-by-the-sea, it would have been her crowning achievement. The New Yorker calls it an "exercise in courage." And numerous writers, including Julian Fellowes of Downton Abbey fame, have stepped in to complete Sanditon on their own.

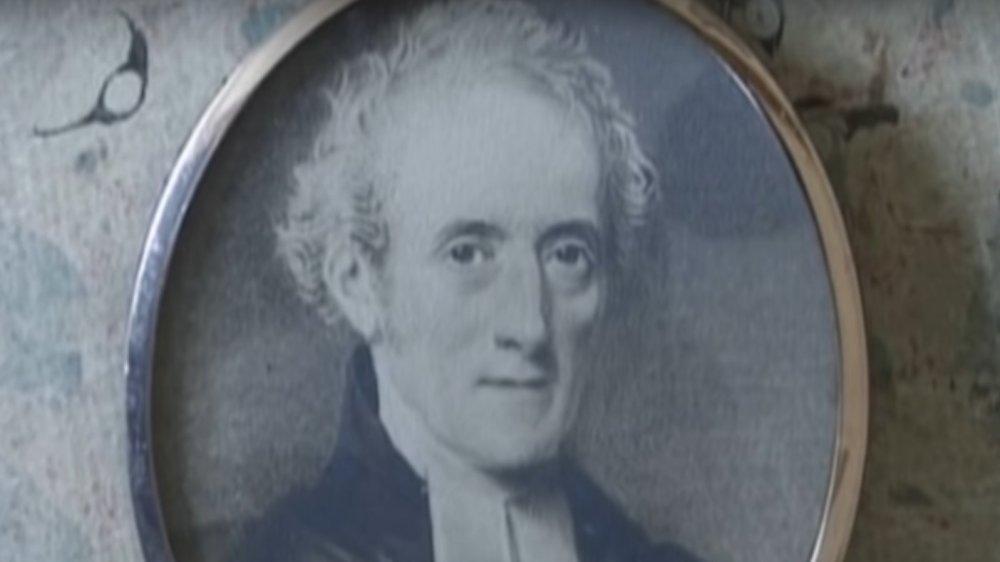

Jane Austen's brother, Henry, misrepresented her after her death

All told, Jane Austen had five brothers and one sister. Of these, she was closest to her sister, Cassandra, and her brother, Henry. Henry was a sort of Renaissance man in reverse. The first of his career moves – that of militiaman and banker — went bust, and he died a poor but largely contented curate. He was also Jane Austen's de facto literary agent. Thankfully, he was better at promoting his sister's work than he was at promoting himself.

He failed her, however, when it came time to shape her legacy. According to this piece in Lapham's Quarterly, the biographical notice Henry wrote for the posthumous publications of Persuasion and Northanger Abbey did his sister the disservice of relegating her to the snore-worthy land of unimpeachable sainthood. "Faultless herself," he wrote, "as nearly as human nature can be, she always sought, in the faults of others, something to excuse, to forgive or forget." Um, is he talking about the same woman who once wrote of her neighbors, "I was as civil to them as their bad breath would allow me?" And the same writer who created such villainesses as Lady Catherine de Bourgh, Mrs. Norris, and Lady Susan?

Henry sold Jane Austen out by trying to cast her as a woman without fault. Then Cassandra finished the job by burning Jane's most biting letters. At least readers have her novels as evidence of her unsparing wit.

A perfect ten (pound note)?

Perhaps because she wrote about youthful romantic love, Jane Austen's looks have long been a matter of debate. Did she, as she might have put it, have a "handsome countenance?" Was she striking enough to turn heads in a crowded ballroom? Or was she, as her portraits suggest, more ironic looking that conventionally pretty? She did attract the attention of at least three men during her lifetime, but that might have been due more to her sparkling personality than her good looks. Her cousin, Phila, found her "not at all pretty." And, according to Wired, when Wordsworth Editions decided to put out another printing of her novels, the publishers photoshopped an image of her so as not to turn off future readers.

The debate got even more heated — and ridiculous — when Austen fans began lobbying to put her on the British £10 note. As NPR reported at the time, the face that appears on the note is not the face Austen was born with. Rather, it's from a portrait painted after her death that undoubtedly smooths out Austen's rougher edges.

Of course, the irony is rich here. Austen was a pioneer, daring to write novels and support herself by her pen in an era that considered literature the realm of men, and women fit only for raising children. The fact that we're still talking about her appearance would most likely have struck the satiric Austen as proof of the durability of human stupidity.