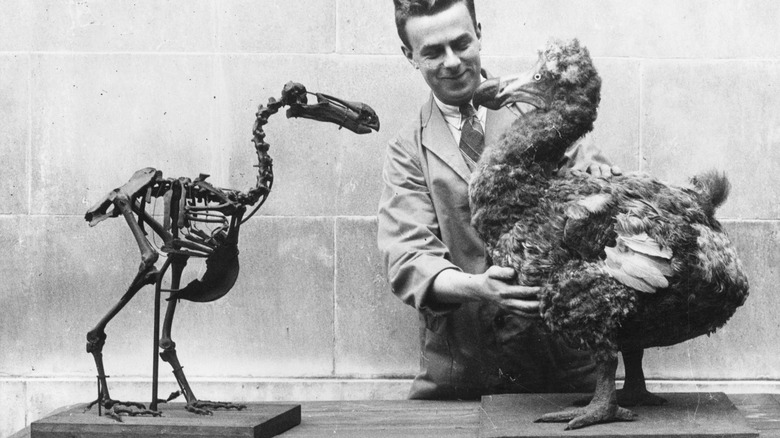

Why The Dodo Bird May Not Be Extinct Forever

Out of all well-known, extinct animal species, the dodo bird definitely has gotten the short end of the reputational stick. After all, what other animal's name is used to mean "idiot"? That reputation goes back to the late 1500s when dodoes first saw human settlers arrive on the tiny island of Mauritius, east of Madagascar and reportedly showed no fear of the new, two-legged invasive species. In this predictably overly simplistic version of the tale, the Dutch settlers thought the 50-pound, oversized turkeys looked like fine meals and eradicated the hapless dumb-dumbs down to the last feather to satiate rabid colonial hunger or something. Reality is a bit more nuanced, and if Colossal Biosciences — a "de-extinction" company — has its way, we might get a chance to give the dodo another shot at making the evolutionary cut.

That's right: In what is not nearly as dangerous a scenario as ignoring "Jurassic Park's" cautionary tale about human hubris leading to dinosauric vengeance, Colossal Biosciences indeed wants to resurrect the dodo. Does this have anything to do with feeding the masses some hefty poultry? Nope. As Scientific American overviews, it's got more to do with seeing if the whole resurrection process can work, particularly the usage of a pigeon surrogate to give birth to a fertilized dodo egg. The ultimate goal is, "to create an animal that can be physically and psychologically well in the environment in which it lives," as Colossal Biosciences' lead paleogeneticist, Beth Shapiro, says. Colossal is also looking to bring back the wooly mammoth, the Tasmania tiger, and more.

Resurrecting the dodo from DNA

The path to dodo petting zoos and house pets goes back to initial dodo DNA research in 2002, which builds on Swiss researcher Friedrich Miescher's initial 1869 DNA discovery. As published by Science in 2002, a Beth Shapiro-led team used dodo mitochondria to uncover the dodo's evolutionary family tree. This may or may not surprise people, but they discovered that the most dodo-like modern species are Columbiformes, aka pigeons and doves. More specifically, Shapiro's team found that the Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica) from the Nicobar Islands west of southern Thailand bore the strongest genetic similarities to the dodo.

With this very big step locked down, Scientific American says that it took a full 20 years, until 2022, to map out the dodo's entire genome. From here, there's the even more herculean task of actually creating a dodo. For mammals, the easiest way to do this is to modify the DNA of a modern genetic relative to match the DNA of the extinct animal as much as possible, insert that modified DNA into the living relative's egg, and then insert the egg into a surrogate to carry the life to term.

Birds can't be cloned in this way, though. Shapiro told Scientific American that there's no way to access a bird egg that's "ready for fertilization but not yet fertilized." Rather, Colossal Biosciences has to manipulate pigeon DNA inside an already-existing egg, meaning that the egg — shell, womb, and all — has to be big enough to carry a dodo to term. "The final version of dodo will emerge from a pigeon that has been engineered to be the size of a dodo," Shapiro said. "So the size of eggs will be consistent."

Where and how would the dodo live?

So if the dodo was brought back to life, what would its life look like? Could we just deposit it back on its home island of Mauritius, say thanks, and then wave goodbye as our ocean liner floats away from shore? The dodo was adapted to its home environment well enough to thrive but died out due to invasive species brought by humans, like rats, goats, and monkeys. Also, settlers deforested the island to make room for plantations, which whittled away at the dodo's habitat. The dodo was an unintended casualty.

So how would anyone think that the dodo would fare better in modernity than it did in the 1700s? If Colossal Biosciences gives life to the dodo, the species would have to be massively protected in order to survive. Vikash Tatayah, Conservation Director of the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation (MWF), told BBC's Discover Wildlife, "The habitat of the dodo has been greatly modified through well over four centuries of human colonization of Mauritius." Remember that Mauritius is the only habitat where the dodo ever existed. On the social side, postdoctoral researcher in paleogenomics at the University of Copenhagen Mikkel Sinding likewise told Scientific American, "There is nobody around to teach the dodo how to be a dodo."

Nonetheless, Colossal Biosciences' Beth Shapiro stated, "If we are going to bring back something that's functionally equivalent to a dodo, then we will have to find, identify or create habitats in which they're able to survive." Such questions need to be answered lock-step with research progress unless we want the dodo to go extinct again.