12 Times People Vanished In The Bermuda Triangle And Were Never Found

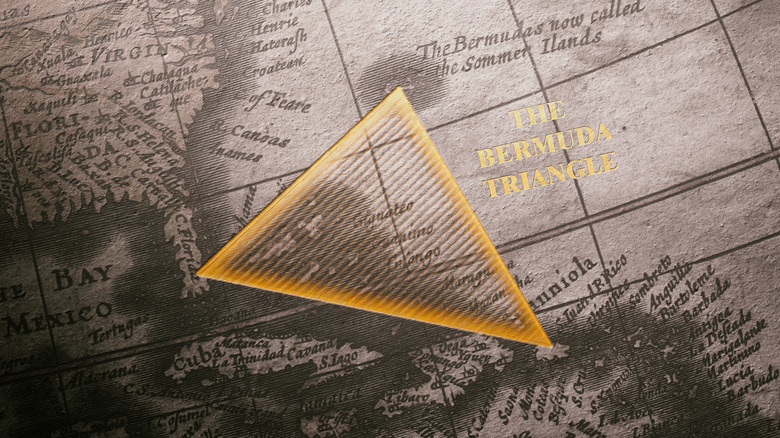

The legend of the Bermuda Triangle has demonstrated real staying power, ever since author Charles Berlitz published a book on the subject in 1974. However, others have taken a more objective look at the data concerning disappearances, finding that this region doesn't have a particularly high accident rate (though one theory alleges it has higher than average methane deposits). Neither do many vessels actually go missing there compared to other places, even though the Bermuda Triangle is host to one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world and often sees major storms and other dramatic weather changes.

The Bermuda Triangle is generally considered to be in the north Atlantic, with Bermuda, Miami, and the Greater Antilles (including Cuba, Jamaica, and Puerto Rico) as its three points. However, unsurprisingly for a place allegedly full of mystery, its precise location is up for debate, with some sources stating it covers 500,000 square miles and others going so far as to say it encompasses over 1,500,000 square miles. It doesn't exactly help that no one officially considers it anything, meaning you're not going to find it marked on official maps.

Still, even if you remain highly skeptical, there are documented, haunting, and yet-unsolved disappearances of people in the Bermuda Triangle, and even entire ships and planes that abruptly vanished. For some, despite the passage of many decades, the question of where they went remains hauntingly unanswered.

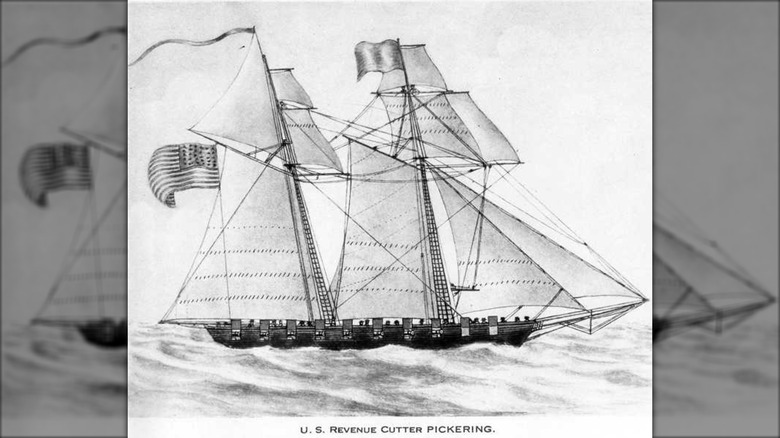

USS Pickering

One of the earliest known incidents connected to the Bermuda Triangle came in August 1800, when the 105-man crew of the USS Pickering seemed to vanish into the waves of the Atlantic. Commissioned in 1798, the ship had already seen its fair share of drama a year later, when it prevailed after an exhausting nine-hour battle with a French privateer vessel in late 1799. It was a significant win, given that the French ship, L'Egypte Conquise, had significantly more firepower and 250 crew members to the Pickering's mere 70. On later voyages, the Pickering and its crew took another four French ships.

In August 1800, the Pickering set sail from Newcastle, Delaware, to the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, where it was set to fall under the command of Commodore Thomas Truxton. But Truxton never saw the ship join his fleet. In fact, no one ever saw the Pickering ever again. No wreckage or any sign of the ship was recovered. That October, Truxton wrote to the Secretary of the Navy that it was a no-show, summing up the general conclusion that the Pickering must have been lost in a terrible storm recorded that September. Still, as matter of fact as Truxton and others may have been — and losing ships in storms was hardly shocking — the image of over 100 crew sailing into oblivion remains haunting.

Flight 19

Things must have seemed normal when Flight 19's training exercise began on December 5, 1945. That afternoon, five Avenger bombers took off from the Naval Air Station at Fort Lauderdale, Florida, carrying 14 aviators. They were to conduct a bombing exercise, fly over the Bahamas, then return home. The group's commander, Lieutenant Charles C. Taylor, was a seasoned pilot who had flown numerous missions in World War II.

But, turning north toward Grand Bahama Island, the group became lost. Then a storm rolled in, making navigation even more confusing. A nearby Navy officer, Lieutenant Robert F. Cox, overhead them and attempted to communicate. Taylor said that his compasses were malfunctioning and he was certain the group was now far off course and closer to the Florida Keys. Contingency plans directed confused pilots to fly west toward the setting sun, but Taylor may have thought he was over the Gulf of Mexico. He continually directed the group to move east, then west, ultimately appearing to move out of radio contact. The last known transmissions from Flight 19 had Taylor referencing dwindling fuel and a potential attempt to ditch the planes in the ocean.

Despite a tremendous search effort, no evidence of the missing squadron was recovered. The likely reality is that the planes ran out of fuel and crashed into the ocean, but the unresolved fate of Flight 19 remains one of the most famous tales of the Bermuda Triangle.

Great Isaac Cay Lighthouse

Great Isaac Cay in the Bahamas is a tiny island barely rising out of the ocean that's long been home to the Great Isaac Lighthouse, constructed in 1850. Today, the lighthouse is unmanned and automated, but back in the 1960s it was still operated by human lighthouse keepers.

On August 4, 1969, others arrived at the cay to investigate inconsistencies in the operation of the light and discovered the keepers had disappeared. Allegedly, all else was in order — it was just that the humans had vanished without a trace. Perhaps Hurricane Ana, which had passed through the area days earlier, swept the unfortunate keepers away in a storm or massive wave.

Or it could be that the keepers were somehow caught up in illegal activities, and drug and arms trafficking had been reported in the area. Of course, others couldn't resist indulging in the spookiness of the Bermuda Triangle, wondering if the unfortunate keepers were somehow affected by paranormal activity (like many other creepy tales of lighthouse ghosts, the specter of a drowned 19th-century woman allegedly walks nearby). Whatever really happened, no one's found clear evidence of the missing lighthouse keepers or their fate to this day.

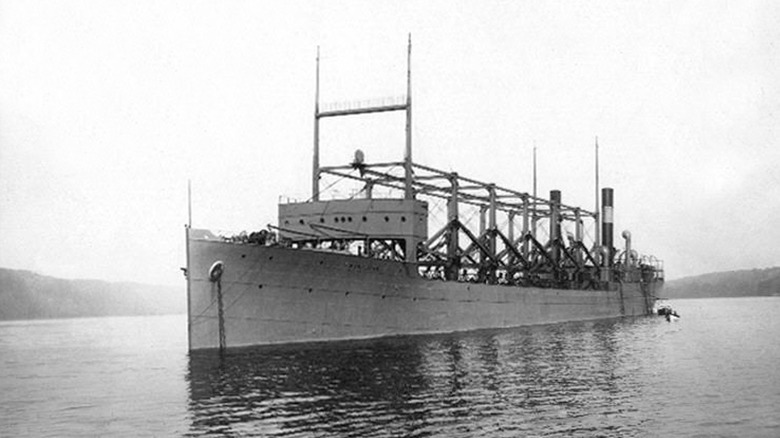

USS Cyclops

In March 1918, the USS Cyclops was one of the largest ships in the U.S. Navy, at almost 550 feet long and with a crew of over 300. Originally built as a coal-carrying collier, on its last voyage the Cyclops was carrying a tremendous 11,000 tons of manganese. The ore was vital to the U.S. steel industry, which was vital after the U.S. entered World War I in 1917.

The Cyclops collected the ore in Brazil, then stopped in Barbados before it was due to head home to Baltimore. This actually wasn't part of the plan, but sailors had noticed that the water level on the heavily loaded ship was too high and docked to inspect. The Cyclops stocked up anyway, bringing on fuel and other supplies for the final push to Baltimore. The Cyclops left Barbados on March 4 and was expected in port on March 13. But it never appeared, and the last known communication merely stated that the weather looked fine and everything was operating as expected.

So, what happened? A storm may have caused the overloaded ship to founder, or previous loads of ore had dangerously corroded the structure of the ship. Others allege that the captain and crew came into conflict and, somehow, a mutiny was to blame for the disappearance of the Cyclops, now considered one of the most nonsensical parts of WWI.

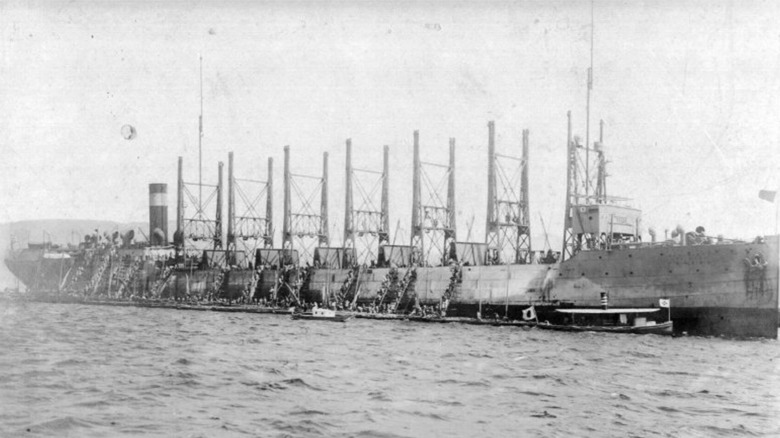

USS Proteus and Nereus

The Nereus and Proteus (AC-10), sister ships to the USS Cyclops, survived WWI but were put into storage after the 1922 Five-Power Treaty limited naval armament. They went back into service as merchant vessels in 1941, transporting bauxite from the Virgin Islands to Quebec. In November of that year, the Proteus left St. Thomas with over 12,000 tons of bauxite and 58 crew, but failed to arrive home. Then, in December, the Nereus set out with some 13,000 tons of bauxite and 61 crew, but likewise failed to reappear.

Because WWII was ongoing, Allied forces weren't keen to boost Axis morale by publicizing lost ships, so said almost nothing about the disappearance. Later, the vessels were simply dropped from active ship lists and few focused on them anyway, as the December 7, 1941 Pearl Harbor attack was commanding headlines.

There was an inquiry, but investigators were stymied by a lack of information. No one reported distress calls, no adverse weather conditions were recorded, and no wreckage was found. A 1974 article published in the Naval Engineers Journal suggested that a combination of cold fronts produced tricky waves that could have damaged the overloaded ships. Surviving sister ships, like the Jason, also showed signs of corrosion after years of carrying sulfur-ridden coal. It could be that the missing ships were dramatically weakened by rust and suffered catastrophic structural damage somewhere in the Bermuda Triangle.

Airborne Transport DC-3

For everyone on the December 28, 1948 flight between San Juan, Puerto Rico, and Miami, Florida, it was set to be a normal trip. But somewhere over the Atlantic, the chartered Douglas DST airliner, often referred to as Airborne Transport DC-3, went missing. According to a 1949 accident report issued by the Civil Aeronautics Board, Captain Robert Linquist and his crew experienced trouble even before takeoff, including a malfunctioning warning light and low batteries. Linquist also noted issues with radio communications, as he could receive but not transmit messages. Linquist took off anyway, believing the batteries would recharge mid-flight via the plane's generators and that this would solve the transmitter issue.

At first, that seemed to be just what happened, but the craft fell out of communication again. Linquist was able to report that he was 50 miles from Miami, but this was received in New Orleans. It could be Linquist was so far off course because he hadn't received reports of wind changes that could have dramatically affected navigation. The plane failed to appear anywhere: Despite a search that extended into the Gulf of Mexico, no evidence of a crash was found and no one was able to conclusively determine what happened to the airliner, its crew, or 29 passengers.

Carroll A. Deering

Though it was found aground off the coast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, in January 1921, it's possible that the Carroll A. Deering passed through some part of the Bermuda Triangle. On what would be its final voyage, the ship was meant to travel from Barbados to Virginia. But two different lightship crews reported that, upon sighting the ship, it was taking an unusual course. One keeper on the Cape Lookout Lightship reported that, when it passed by on January 29, a crewmember from the Deering said it had lost its anchors. By January 31, the Carroll A. Deering was spotted on the shoals off Cape Hatteras. Heavy seas prevented anyone from boarding until February 4, when sailors finally made their way to the soon-to-be-notorious ghost ship. They found the sails unfurled, but the lifeboats were gone, along with valuables and personal items. No crewmembers were in sight.

Among the many theories bandied about to explain the disappearance, the most likely is that the ship ran aground in heavy seas. The crew faced a terrible choice: stay on the storm-lashed and possibly sinking ship, or load into the lifeboats and make for shore nine miles away. Given the missing lifeboats, they likely took the second option but perished anyway. Others speculate that the ship was captured or collided with another lost vessel, the Hewitt. Some wonder if a mutiny took place, but this doesn't quite explain why the ship would have crashed into the shoals.

BSAA Star Tiger and Ariel

The Star Tiger and Star Ariel were both British passenger airliners that disappeared in January 1948 and January 1949, respectively. Both were converted Avro Tudor IV planes of the British South American Airways (BSAA) fleet and were traveling routes that took them from London to Bermuda (the Star Ariel was also bound for Kingston, Jamaica). Both disappeared mid-flight with little warning: The Star Tiger carried 25 passengers and six crew members, while the Star Ariel had 20 aboard.

In a 1948 accident report, the British Ministry of Civil Aviation noted that the Star Tiger experienced numerous issues, including a faulty cabin heater and one malfunctioning compass. Captain Brian W. McMillan elected to fly at a dramatically low altitude, possibly to help the heater issue, though he also appears to have overloaded the craft with fuel and passengers. This meant the Star Tiger would have burned fuel much faster, and as close as they were to the water, if an emergency happened, the Star Tiger likely hit the ocean surface in mere seconds.

Just a year later, the Star Ariel disappeared at a much higher altitude of about 18,000 feet. An investigation ruled out fuel issues, weather, and pilot error, but former BSAA pilots told the BBC that the cabin heater and hydraulic systems were in close proximity. Leaking hydraulic fluid could have come into contact with the heater and caused a sudden explosion.

Revonoc

The Revonoc, which disappeared in January 1958, was a racing yacht with a crew of just five. Yet that crew included experienced sailors like owner Harvey Conover (the ship's name was his own spelled backward). Conover, his wife, their adult son Larry, Larry's wife Mary, and friend William Fluegelman all set out from Key West. Their apparent goal was to dock in Miami, though others suggested that they were actually trying to make it to Nassau in the Bahamas. Wherever they meant to go, something went terribly wrong.

As the day continued, authorities issued increasingly dire warnings about winds in the area. By the afternoon of Thursday, January 2, weather stations were warning of a gale with winds potentially exceeding 50 miles per hour. Later, gusts of more than 70 miles per hour were recorded around Miami. Meanwhile, the Revonoc failed to appear as expected.

After a two-day search, its dinghy was found about 80 miles north of Miami, half-sunk and without any sign of the crew. The younger Conovers left behind two children, 3-year-old Aileen and 18-month-old Sarah. Speaking to Spokane's The Spokesman-Review in 2023, Sarah says she believes the ship couldn't stay upright in heavy seas whipped up by the gale. A passing shrimp boat even saw five people trailing from ropes behind a foundering craft, but immense waves, strong winds, and a malfunctioning motor kept them from attempting rescue. This was likely the last known sighting of the doomed ship and its crew.

Fairchild C-119 Flying Boxcar

By 1965, the Yankee Route was a well-trod (or well-flown) route across the Atlantic just south of Florida. Yet, while many aircraft had traveled through the region without incident, that was not the case for the Fairchild C-119 "Flying Boxcar" piloted by Major Louis Giuntoli on June 5 of that year. Giuntoli, along with nine other members of the 440th Airlift Wing, was set to arrive at Grand Turk Island in the Bahamas that evening. It was a fairly boring affair of dropping off supplies and support crew, then hopping over to a pick-up in Puerto Rico before delivering other supplies to a base in the Dominican Republic. Yet, after a routine communication, the C-119 seemingly flew into oblivion. It never arrived at the expected time nor place on Grand Turk Island, kicking off a massive search.

Searchers did find part of the missing airplane, but it was a scanty collection of debris and a single wheel that offered little clue as to how the plane went down. Some thought it strange that little else was found, as the sort of sudden explosion that might have caught a crew of experienced airmen unawares would have likely left more evidence.

Witchcraft

On December 24, 1967, Dan Burrack and Father Patrick Horgan took Burrack's 23-foot craft just off Miami Beach to view holiday lights. But what was likely meant only to be a cheerful jaunt soon turned dire, as around 9 p.m., Burrack contacted the Coast Guard to say that the Witchcraft was in distress. Burrack claimed that the powerboat had hit an unidentified object and was unable to navigate. He also stated that the Witchcraft was near Buoy No. 7 in the harbor, making it all the easier for help to locate them.

But, when the Coast Guard arrived 18 minutes later to give the two men a ride back to shore, they found only empty water, even though they were just a mile or so off the beach, well within sight of Miami. Even stranger, the yacht was reportedly equipped with a flotation device that would have at least kept it just below the surface, well within sight of potential rescuers. Despite yet another massive search that grew to include six planes and four U.S. military ships, no sign of either man or their boat was found.

Where could they have gone in such a short time? Perhaps the flotation device wasn't quite as foolproof as Burrack and Horgan might have hoped. Or, as their families have allegedly suggested, it could be that one or both of the men were caught up in a maritime robbery and the boat was intentionally discarded.

Perry Cohen and Austin Stephanos

Perry Cohen and Austin Stephanos were last seen on July 24, 2015, when they left Jupiter, Florida, in a 19-foot boat. Though both boys were only 14 years old, their families said that Cohen and Stephanos often went fishing and boating, but this time the duo met bad weather that apparently capsized their boat. The vessel was found about 67 miles north of Daytona Beach but was pushed out to sea before retrieval. Later, a Norwegian ship came across it, this time about 100 miles from Bermuda. Captain Harvard Melvaer told CBS12 that the boat was in one piece, with a complete hull, a seemingly unaffected engine, and Stephanos' iPhone inside. Other sources indicate that the battery and boat ignition were switched off.

Cohen's family had apparently set limits on his seafaring activities and the unauthorized trip caused a major rift between the families. Testimony from the boys' friends and communications indicate the two realized they were encountering poor weather. Some suggested that Cohen and Stephanos were headed to the Bahamas, though their families argued against this as the two didn't have passports or enough fuel to make the trip. And while Cohen and Stephanos weren't technically inside the commonly accepted bounds of the Bermuda Triangle, it's not entirely clear where they were headed. Their course — intentional or otherwise — may have taken them into the region.