Strange Rules Soldiers Followed During World War II

For many of the countries involved, World War II was a "total war," meaning that effectively every resource the nation could harness was directed toward the war effort. This led to strict rules coming into effect across entire societies, affecting wartime activities on the home front, the role of women in the conflict, and, perhaps most centrally, the soldiers who made up each country's fighting forces.

The fighting men (and sometimes women) who fought and died across Europe, northern Africa, and the complex Asia-Pacific theater did so while obeying rules and instructions dictated both by the governments and higher-ups they reported to and by the realities they faced on the battlefield. While these directives for behavior varied widely, they all existed to serve the military and, ultimately, political ends of the governments involved in the fighting. The individual good of the soldiers, though it sometimes matched the overall wartime goals of their countries, were at best secondary concerns.

Stay as clean as circumstances permit (all armies)

Disease was a serious risk for deployed soldiers, and while battle conditions often meant hygiene took a back seat, cleanliness could prevent or slow the spread of dangerous diseases. Typhus, a bacterial disease spread by lice (which themselves spread easily in crowded wartime conditions), was so feared by German administrators that enterprising Polish doctors faked an outbreak to keep workers from being deported to Germany for forced labor. Dysentery, a catchall term for diseases causing serious diarrhea (often containing blood) has plagued armies for centuries. (As you can imagine, an army confined to the latrines is not the most effective fighting force.) Handwashing, general cleanliness, and exterminating lice through hot showers and aggressive laundering went a long way toward limiting the spread of conditions like these.

In addition to straightforward personal hygiene, maintaining a sanitary environment was also emphasized in wartime messaging. Cleaning latrines, covering trash, and managing insect populations were simple (if, in the case of cleaning latrines, unpleasant) actions enlisted soldiers could take that limited the spread of disease and, consequently, kept more men in fighting shape.

Keep mum (everyone)

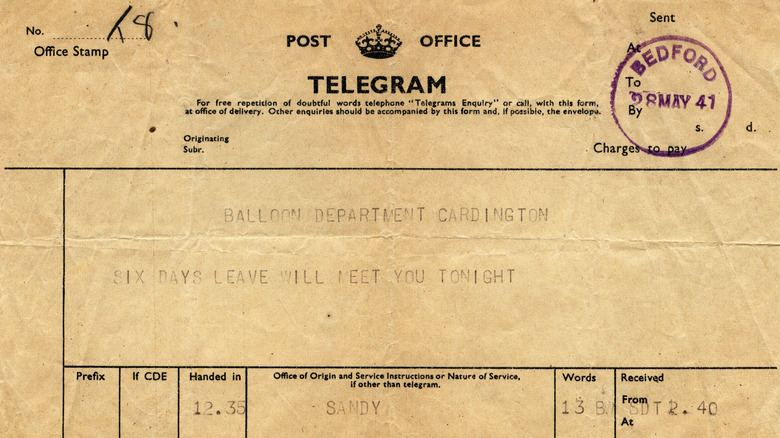

Secrecy is key during wartime: Put simply, if the enemy knows where you're going, they know where to put their guns. Both Axis and Allied governments worked hard to conceal the details of their war plans from the enemy, which in part involved making sure the soldiers enacting those plans knew to keep their mouths shut. Starting in March 1940 (so, just weeks before the invasions of Denmark, Norway, the Low Countries, and France), Nazi censors began monitoring mail going to, from, and between German soldiers. Among various other restrictions, soldiers were to write only in European languages (which explicitly excluded Morse code), refrain from giving details of Axis or Allied movements or attacks, and send no pictures of important military installations. Theoretically, soldiers or their correspondents could be prosecuted for "subversion" depending on the contents of their letters, though the huge volume of mail meant enforcement could never be total. (Mail was restricted if not completely stopped for inmates in POW and concentration camps; according to the Geneva Convention, denial of mail service is another in the Third Reich's long list of human rights offenses.)

The Allies also censored mail, and with similar aims in mind. Scholars note that self-censorship was also an important factor: Public information campaigns informed soldiers and their home-front correspondents of the kind of information that might delight an enemy who intercepted a letter, and so potentially dangerous information often never reached the page.

Never give up (Japan)

When Japan formally surrendered in August 1945, its forces still held a number of positions in China and Southeast Asia, as well as several Pacific Islands. While most of the soldiers manning these outposts would return to Japan relatively soon, a handful of holdouts remained, driven by honor and suspicion that the surrender instructions were an American ruse. Some of these Japanese servicemen refused to surrender for years or decades after the empire's surrender, hiding out and foraging on islands such as Guam, Iwo Jima, and Lubang in the Philippines.

Among the most notable of the holdouts to return to Japan was Shoichi Yokoi, the last of nearly 5,000 Japanese fighters who had refused to surrender after Guam fell to U.S. forces. Most were ultimately captured or killed by the end of the war in 1945, but Yokoi hid out until 1972, ironically missing the entire initial run of "Gilligan's Island," until he was captured by local fishermen. He apologized profusely and publicly to the emperor upon his return. Two years later, Hiroo Onoda was discovered on Lubang, refusing to be repatriated until his commanding officer arrived and directly ordered him to do so. As recently as 2005, two elderly men emerged in Mindanao (also in the Philippines) claiming to be holdouts, though their claims met with some skepticism.

Never desert (USA, Soviet Union)

Desertion, or the abandonment of one's military unit, is a serious offense under military codes of discipline, with death often among the available penalties. Among the WWII combatants, the Soviet Union took an especially dim view of desertion, and during the German onslaught, Stalin issued his anti-desertion Order 270. In this impassioned document, Stalin explicitly names disappointing generals and orders that even when surrounded, Soviet units are to fight to the death rather than surrender, on pain of being shot on the battlefield. Families of commanders or soldiers judged to have resisted insufficiently were subject to arrest and denial of benefits. Though some Soviet deserters were shot, to shoot too many was counterproductive: The most common fate was to be sent back to the front, either in one's own unit or a special penal unit assigned dangerous work.

In contrast, the United States executed only one soldier for desertion during the war: Private Eddie Slovik. Slovik, who had a minor criminal record in the U.S. (as well as a wife), slipped away after freezing under bombardment during the punishing Battle of Hürtgen Forest in the autumn of 1944, returning, being warned that to leave without permission again would be considered desertion, and leaving again. General Eisenhower wished to make an example, and Slovik was it, facing a firing squad in January 1945 — the first American to die for desertion since 1864, and as of today the most recent U.S. serviceman to meet that fate.

Don't give an inch (Soviet Union and Germany)

When Hitler's forces invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, they opened up a huge, sprawling, complicated battlefront that would claim millions of combatant and civilian lives over the coming years. The initially unprepared Soviets were able to rally, and (at great cost) Stalin's armies slowed the German advance and then rolled it back, ultimately contributing immeasurably to the Allied victory. As part of the Soviet effort to stanch the flow of better-organized German troops into Soviet territory, Stalin issued Order 270, which forbade troops to retreat or surrender, even if surrounded, on threat of death for themselves and punishment for their families.

As the wheel of fate turned, the Soviet forces slowly, bloodily took the upper hand. Germany dedicated two armies to the capture of Stalingrad in southern Russia, beyond which lay the important Soviet petroleum production in the Caucasus. The Soviets narrowly retained the city and mounted a colossal counterattack, ultimately encircling the German forces. Hitler forbade either retreat or surrender: Losing a position so close to the psychologically and strategically significant Volga River was unthinkable, and he refused even to let the entrapped forces fight west toward a supplemental German force sent to rescue them. But Hitler's feelings about the issue didn't matter. In January 1943, the shattered and freezing remnant of a major German army group, having been denied the chance to fight its way out, surrendered.

If you have to retreat, leave nothing for the enemy (Soviet Union)

Scorched-earth warfare is a tactic as old as conflict. Simply put, this strategy requires leaving nothing available for the enemy: An invading or retreating army will take, burn, blow up, destroy, or disable anything it can to deny its use to the enemy. An additional "benefit" is that the destruction of scorched-earth tactics can limit a civilian population's willingness or ability to wage a war, as well as collectively punish areas considered to deserve it.

Both Axis and Allied forces used scorched-earth approaches during the war, with one of the most striking examples coming in the early stages of the German invasion of the Soviet Union. Soviet units smashed roads and bridges, destroyed food stores, and in some cases broke down entire factories and sent them further east for reassembly. Since Soviet trains used a different gauge of track than German locomotives did, they also made sure no operational railroad cars were left behind for the approaching Nazis. The Soviets also evacuated more than 17 million of their citizens from the combat zone, denying the Germans this colossal pool of labor and conscripts and preserving it for their own war effort.

Nazis notoriously left ruins behind when they retreated, but thankfully, one of the worst proposed scorched-earth attacks never came to pass. Faced with the imminent liberation of Paris, Hitler ordered the French capital destroyed. A horrified General Dietrich von Choltitz stalled until the Allies retook the City of Lights.

Just follow orders (everyone)

After the last shots of World War II were fired, the victorious Allies were left to handle the men (and some women) who had carried out the Axis powers' crimes against humanity. (The Allies' own crimes were generally not punished, since they won.) Key Nazis were taken to Nuremberg, a Bavarian city that had been important in Nazi myth-making, to face trial. There, a number of defendants presented the defense that they had been following orders and thus could not be personally responsible for what happened. They were instruments; guilt lay with those who had given the orders. (And Hitler, from whom most orders had flowed, was conveniently dead.)

The judges, drawn from the victorious major Allied states of France, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, rejected this defense. They wrote, in a decision that seems common sense today but was an important legal precedent at the time, that the soldiers who had committed atrocities knew, or at least should have known, that what they were doing was wrong. Furthermore, while it might have been dangerous for them to disobey these orders, they were not at immediate risk of death for doing so. While subsequent war criminals and persons committing crimes against humanity have not always (or even usually) been brought to justice, Nuremberg at least established the right of the world to hold such wrongdoers accountable.

Be flexible (Italy)

Fresh off colonialist adventures in Ethiopia and Albania, Italy entered World War II as Nazi Germany's primary European ally. Benito Mussolini's Italy invented the term "fascism" and hosted one nexus of the Rome-Berlin axis after which the infamous alliance was named. Hitler even apparently admired Mussolini (though it was not wholly reciprocated), and Italy, its government, and its soldiers were at the center of the Axis war project, committing troops to battlefronts across Europe.

Italy's gung-ho approach to an all-fascist Europe cracked in 1943. Several factors – relatively accurate news from Vatican radio, reemerging antifascist resistance, labor disputes, and Allied bombing raids, along with a long string of military fiascos — effectively obliterated the Italian will to continue the war. In late July, the seldom-relevant King Victor Emmanuel III dismissed Mussolini, and a caretaker government took control, sort of: They were too inept even to give the military orders to defend Rome, and Germany soon overran northern and central Italy. Allied commanders (correctly) assumed that Italy's wartime struggles would turn most Italians, including those in the armed forces, against Germany, and in October 1943, what was left of the Italian fighting forces joined the effort to expel Hitler's men from the peninsula. In under a year, Italian soldiers had gone from fascist tagalongs to freedom fighters supporting one of the many Allied prongs rolling back Nazi forces.

Reconstitute (France, Poland)

Poland and France, Germany's largest and strongest direct neighbors, both came under foreign occupation relatively early in the war. Their armies, though battered, were not completely destroyed, and both countries were able to reconstitute their armed forces to participate in the ultimate defeat of the Axis, gathering fighters already deployed overseas, escapees from German invasion, and freed POWs. Using bases in the United Kingdom and personnel and resources from across France's colonial empire in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific, the French general Charles de Gaulle cobbled together an effective fighting force. These Free French fighters coordinated with their allies in the resistance in occupied France while also fighting alongside British troops in Africa and Italy, eventually participating in the liberation of France itself.

Poland, as usual, was in for a wilder ride. During the initial two-front invasion by Nazi Germany and the opportunistic Soviets, a number of Polish soldiers evacuated to France and the United Kingdom; others were captured by the Soviets. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union, the Soviets recruited a (presumably delighted) captured Polish general to lead an army of Polish prisoners against the Germans. These freed soldiers trained in ... Iran, of course, joining their compatriots who had fled to Britain and were now helping the joint British-Soviet occupation of parts of Iran to keep it out of the Axis (and its oil in Allied hands). These adventuring free Polish units fought hard and with distinction alongside the other Allies.

Watch out for VIPs (Allies)

As Allied soldiers approached the university city of Bonn in western Germany, researchers at the university frantically tried to destroy records implicating them in Germany's crimes. A quick-thinking Polish lab technician salvaged an unsuccessfully flushed dossier of German and Austrian scientists, complete with identifying details (including the address of a functionary with even more dirt on Nazi scientists). This information was used to make, effectively, a list for one of the most grim scavenger hunts in modern history. America wanted to benefit from these scientific minds nearly as much as it wanted to prevent the Soviets from doing so, and so Operation Paperclip, a program to snag and use these experts, was born. American forces capturing or accepting the surrenders of Nazi forces now had a list of VIPs with whom the U.S. might be willing to cut a deal, offering a new life and effective amnesty in return for turning their coats. Individual soldiers sometimes made the collars: Werhner von Braun, Operation Paperclip poster boy and a brilliant rocket scientist later key to the U.S. space program, surrendered to a private monitoring a rural road in Austria.

Look sharp (USA)

General George Patton was one of the United States' most effective commanders of WWII, commanding forces taking Sicily before playing a pivotal role in the great post-D-Day thrust across northern France and Belgium into Germany. His record of success meant that the few men who outranked him had to put up with his eccentricities, most prominently a searing hot temper (he personally shot two Italian mules for being in the way) and a focus on impeccable dress even in battle. This urge to present a neat appearance influenced his standards for troops under his command, who had to wear neckties in battle ... even in hot, sticky Sicily. (Perhaps even worse, they had to keep their helmets strapped on in the latrine, one of very few places during wartime one might expect freedom of action.) Reportedly, the only way out of the necktie decree was to present a doctor's note, as one soldier who had survived having his throat cut by a German soldier did.

The necktie, interestingly, owes its origin to battle dress. Croatian mercenaries fighting for France in the 1630s wore bright cloths to close the necks of their jackets. The French, alert to fashion, adopted this scarf as a decorative flair and named it a cravat as their best attempt at pronouncing "Hrvat," the Croatian word for "Croat."

No dancing (Finland)

Finland was a secondary but important participant in WWII. The Soviets took advantage of the general disorder of 1939 to attempt to reconquer Finland, which had become independent of the Russian Empire in 1917. Fierce Finnish resistance limited their losses, and when Germany came knocking with an offer, Finland answered, allowing German forces to cross their territory and participating in the war against the Soviets, including the horrific Siege of Leningrad.

Given all this stress, it's easy to imagine a Finnish fighter wanting to spend his time on leave unwinding, maybe even heading to a dance to meet some women. Unfortunately for this theoretical soldier (and any women who might have enjoyed dancing with him), public dances were banned in Finland during two wars against the Soviet Union. The sour-faced Evangelical-Lutheran church and its allies in the temperance movement strongly opposed partner dancing, fearing it to be the first step to drinking and premarital sex. Given the somber and dutiful mood expected of the populace during the national emergency of the war, this attitude was formalized into a ban on public dancing in December 1939, covering both civilians and members of the armed services on leave. People flouted the ban as time wore on, as nearly five years without a dance was a lot to ask, but dances were raided and a number of people punished. (Two were even killed in such raids.) After a separate war with the Soviets concluded in 1944, the Finns had to put up with retreating Germans spoiling the terrain, the loss of the province of Karelia, and shortages, but they could again distract themselves with dancing.