Things That Don't Make Sense About The American Revolutionary War

If you grow up in the United States, then by the time you reach adulthood, you've heard the tale of the American Revolution again and again. Perhaps, with the right sort of history teacher, you were able to get past the sort of starry-eyed hagiography that turns real people like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson into mythical figures. But, even if you had the joy of learning from an enthusiastic, intelligent teacher and were an engaged student yourself, there remain some odd sticking points in the tale of the revolution.

Sometimes, it's the uncomfortable sense that some people are left out of that story, or maybe even that quite a lot of voices are missing. Could we have forgotten a patriotic female spy, for instance? Or maybe too many of us have been so taken by that notion that we simply made her up. Perhaps the issue you can't release centers on missed connections, or opportunities not taken, as when a terrifyingly good sharpshooter had George Washington in his sights ... and then decided to back down. Whatever it is, there are plenty of things about one of the most pivotal wars in American history that don't always make sense.

Why didn't Britain just give the colonists representation?

Though teasing out the causes of the American Revolution is seriously complicated, one particular motivation stands out: representation. As the revolution rumbled into life, many colonists complained that they were being hit unfairly with new taxes, laws, and other restrictions without proper representation in Parliament. In 1764, Massachusetts colonist James Otis published "The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved," in which he argued that anyone taxed by Britain had the right to representation. Otis wrote: "... every part [of the British Empire] has a right to be represented in the supreme or some subordinate legislature: That the refusal of this, would seem to be a contradiction in practice to the theory of the constitution." Giving the colonies a fair say wouldn't just be good for the colonies. Instead, Otis argued that it would strengthen Britain further "and render it invulnerable and perpetual."

Even if Britain didn't quite agree — some have argued that colonial representation would have shifted power away from British elites — why didn't it change course when rebellion became war? In fact, it did. In 1778, Britain sent a group of representatives known as the Carlisle Commission (satirically depicted above) to the colonies. Their proposal: stop the war and you'll get to rule yourselves. But, feeling the momentum of the revolution — and maybe also smarting at allegations of corruption and collaboration with the commission — the Continental Congress nixed the proposal (though some wonder if it would have been so roundly rejected had all representatives been present).

Why do we get the taxation issues so wrong?

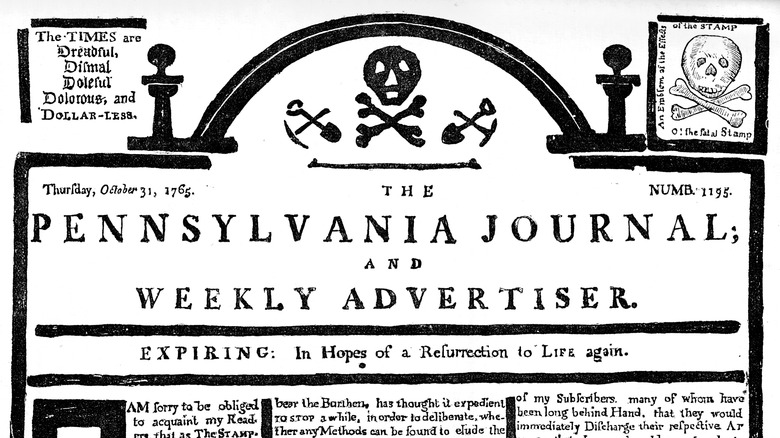

Despite the oft-repeated complaint of "taxation without representation," the American Revolution didn't entirely hinge on taxes. The Stamp Act, for instance, was passed in 1765 and was the first direct tax on colonial America. Paper goods bore a namesake stamp to show the tax had been paid (and that money was being funneled back to debt-loaded Britain). The move was deeply unpopular, led to the growth of nascent revolutionary group Sons of Liberty, and was repealed the very next year. Other taxes were levied, but the reality was that colonists were actually taxed at seriously low rates. How low? A scanty 1-1.5%, compared to the 5-7% faced by British people just before the revolution. In fact, colonists made more money, scored more land, and were far more literate than their British cousins (though they also had very little governmental support from the crown).

The taxation issue wasn't so much about harsh costs as it was about colonists having a say in what taxes could be enacted and how. Neither was this the sole cause of the war, which came about after a complex interplay of factors that included other unpopular acts and a growing sense of an identity separate from Britain. Bloody incidents, like the 1770 Boston Massacre, and the far less gory but supremely wasteful Boston Tea Party of 1773 (in which around $1.5 million in modern USD was tossed into Boston Harbor in the form of tea) hardly helped things.

How come the richest colonists risked major upset by rebelling?

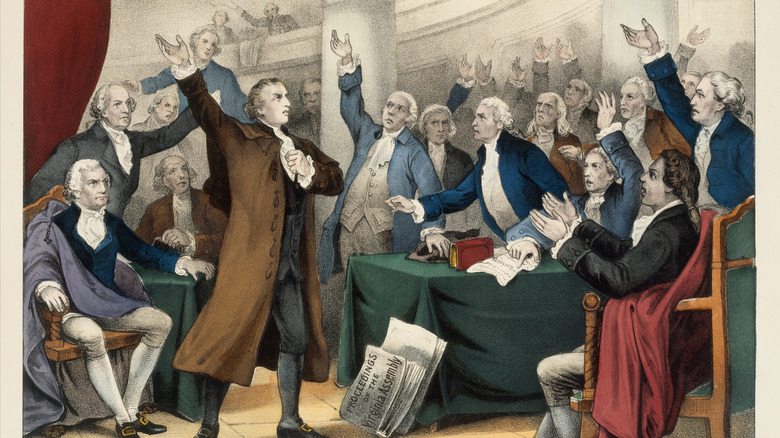

While it's easy to understand why farmers and other working-class folks might support a revolution, there was a surprising group of budding revolutionaries: elites. Over in Virginia, easily one of the richest colonies, elites sometimes supported rebellion. But, not only did high-ranking members of society get there under the colonial system, they also found themselves enjoying numerous British imports. So, why would they choose to support a breakaway republic?

Not all Virginia elites were immediately ready to rebel. In fact, many initially supported the 1765 Stamp Act. But the act was quickly unpopular, especially when some elites found themselves in unstable financial speculations. For some, plum trading situations were hampered by British taxes, as were fancy foreign imports. Trade duties were also imposed on the import of enslaved Africans, who proved vital to the colony's all-important tobacco industry.

All told, numerous wealthy planters worried their financial situation was being upset by money-hungry Britain. Some expressed concern that growing discontent might break apart the social order, giving enslaved people the idea that they were humans who deserved equal rights on par with whites. Supporting the revolution became an avenue for elites to uphold a beneficial financial and social order, but without interference from Britain. Indeed, while slavery was finally outlawed in the British Empire in the 1830s (though exploitative labor conditions existed for far longer), it took bloody civil war and a constitutional amendment to outlaw U.S. slavery in 1865.

Why did France decide to help out the rebels?

Even casual students of the American Revolution soon understand that the colonists were never going to win the war on their own. Britain was simply too powerful ... until France came along. But while it's clear that France and a few other nations lent serious help to the budding republic, it's not quite so obvious why. Besides the major cultural differences between the two nations — at the time, France was a pre-revolution kingdom that broadly supported both the aristocracy and Catholicism — there are practical issues, too. Why would France train, supply, and fund ragtag rebels facing off against a growing British empire?

For one, the ragtag bit is more a false American Revolution fact than strict reality. Moreover, those cultural differences may not have been quite so stark. Sure, the ancien régime of King Louis XVI was still going on, but the Enlightenment had also come to France in full force, bringing with it new ideas about society and government that were echoed by what Thomas Jefferson and company wrote in the Declaration of Independence.

There were political expediencies to consider, also. For one, France had long been a rival to Britain. Helping the rebels meant striking back against an old enemy ... not to mention making friends with a new nation that produced all sorts of profitable crops and goods. That's likely why other nations lent their support, including funds supplied by Spain and the Netherlands.

How did George Washington make it out of the Battle of Brandywine?

There were plenty of times during the American Revolution when George Washington barely escaped serious injury or death. He was the subject of a 1776 assassination plot, skirted capture by the British in New York, and led a December 1776 surprise attack that could have proven disastrous (but was the rebels' first real win of the war).

Washington's closest brush came at the September 11, 1777 Battle of Brandywine. Lieutenant-General Sir William Howe essentially forced Washington's army into battle at Brandywine Creek, near Philadelphia. It was a loss for the Continentals but not a major defeat, since many colonial soldiers retreated safely thanks to well-organized tactics. However, Washington himself had an alarmingly close call. For a few moments at least, he had been in the sights of a deadly enemy sharpshooter.

That enemy was Captain Patrick Ferguson, widely touted as the best marksman in the British army. Crouched in hiding along the creek, Ferguson saw a group of rebel officers pass nearby. He ordered the soldiers under his command to shoot but, at the last minute, canceled his directive. Only later did Ferguson learn one of those officers was Washington. Reportedly, he thought "it was not pleasant to fire at the back of an unoffending individual who was acquitting himself very coolly of his duty" (via "The Philadelphia Campaign: Brandywine and the Fall of Philadelphia"). Washington would die rather tragically of a sudden illness in 1799, though he at least passed in bed at his estate and not on a battlefield.

Why are we still arguing about Charles Lee's role?

Who, exactly, was Charles Lee? The English-born Lee was once a British officer who turned to the colonists' side in 1775. He was commissioned as a major general in the Continental Army and at first enjoyed the acclaim of his fellow commanders, eventually becoming second-in-command of the army. But Lee came into such frequent and dramatic conflict with Washington that his once-sterling reputation began to take on a serious tarnish — he may now be considered one of the worst generals of the American Revolution.

At the June 28, 1778 Battle of Monmouth, Washington criticized Lee for his messy, confusing command. Lee's response was so spicy that he was charged with insubordination and temporarily removed from command. Clearly not knowing when he ought to mind his manners, Lee became such a constant problem that he was accused of treason and permanently dismissed from command in 1780.

While his rash decisions are plenty confusing, an earlier incident in Lee's career makes things even odder. In 1776, after the British took New York City, Lee was captured and held until 1778. During that time, he wrote to British commander-in-chief Sir William Howe with advice on how to defeat the rebels (these letters didn't come out until after Lee's 1782 death). Had he turned traitor yet again? Some allege he even came up with a more concrete plan to hand the colonies back to Britain. Others wonder if he may have been a canny double agent or simply a difficult man, who perhaps wrestled with untreated mental health issues.

Why did Washington execute John André?

In a war full of dramatic episodes, few are more gut-wrenching than the story of British Major John André. He is perhaps most notorious for acting as Benedict Arnold's contact, facilitating Arnold's betrayal and an attempted takeover of the strategic fort at West Point, New York. Yet the plot failed and André was captured and executed in October 1780.

Though André's end came under orders from Washington, the motivations behind this decision are less than clear. For one, Washington was said to have admired André and even may have viewed him as something of a noble poor sap caught between two sides. He even offered to return André to the British in exchange for Arnold, but was turned down.

Still, there are details here that don't obviously make sense, as Washington still ordered the execution and in somewhat of an embarrassing fashion. The day before his death, André wrote to Washington "that if ought in my Character impresses you [...] I shall experience the Operation of these Feelings in your Breast by being informed that I am not to die on a Gibbet." Other officers also thought André should at least be given the dignity of death via firing squad and not the hanging accorded to common criminals. Yet Washington (and other Continental Army commanders) voted to have him hanged anyway. Major General Nathanael Greene argued that it was only fitting for a spy, but Washington never made his own motivations clear.

What's the truth about agent 355?

One serious boost to the war came from the Long Island spy ring that helped George Washington win the American Revolution. Known as the Culper Spy Ring, it was based in Setauket, Long Island, home of spy ring organizer and cavalry officer Benjamin Tallmadge. Many of those involved have since been revealed, including farmer Abraham Woodhull and sailor Caleb Brewster. But one member of the ring remains unknown to this day: agent 355.

An individual coded 355 is referenced by Tallmadge, who used numbers and code names to conceal identities. The number 355 simply denotes "lady" and is only mentioned once by Tallmadge. There, he writes that "[I] think by the assistance of a 355 of my acquaintance, [we] shall be able to out wit them all" (via "General Washington's Spies"). However, a close reading hints that he may not be talking about a full-on spy, but using a generic term — not a 007-style codename.

Still, people love to speculate about this woman's identity. Some point to Anna Strong, a Long Island resident who was Woodhull's neighbor and whose husband supported the rebellion. She allegedly did communicate with agents, reportedly hanging a black petticoat on a washing line if a message was ready for pickup. Other candidates include an unnamed lover of lead agent Robert Townsend (said to have died in a prison ship, a real messed-up situation that happened to others during the Revolution) to none other than Benedict Arnold's beau, Peggy Shippen.

Why don't we know for sure if anyone's buried at Valley Forge?

There's no denying that the winter of 1777-1778 in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, was brutal. Continental Army soldiers camped there suffered through frigid temperatures, poor supplies, and disease. Though the survivors would come out of the experience as a highly-trained and organized force (thanks largely to the help of the Prussian Baron von Steuben), it was no easy task. Some 2,000 men died, often from typhus, typhoid, influenza, or dysentery. So, Valley Forge must be practically littered with graves. Only, historical records indicate that the most ill were sent out of the camp to hospitals. If they died, they would have been buried in nearby graveyards, not the camp.

Still, locals began to claim that soldiers were buried north of the encampment. By the 19th century, the area was considered the resting site of perhaps thousands, and signs (including some placed by the WPA in the 1930s) profess to mark a scattering of Revolution-era graves. At least one 1902 account claims that construction workers uncovered five graves complete with skeletal remains (via National Park Service).

Yet there's no clear evidence of Valley Forge graves belonging to Washington's soldiers. The National Park Service has conducted numerous archaeological excavations in Valley Forge National Historical Park, but produced no definitive evidence of graves. For such a pivotal episode in American history, it's odd that we don't know more about the final resting places of some of the soldiers involved.

Who exactly was the revolution for?

Take a look at the opening lines of the Declaration of Independence, which boldly declares "that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." But dig a little deeper, and that notion is complicated by some Founding Fathers themselves.

In a 1776 letter to James Sullivan, John Adams contemplated the idea of letting non-elites vote. Adams thought the notion dangerous, or at least presented a major political headache. "There will be no End of it," Adams fretted. "New Claims will arise. Women will demand a Vote. Lads from 12 to 21 will think their Rights not enough attended to, and every Man, who has not a Farthing, will demand an equal Voice with any other in all Acts of State. It tends to confound and destroy all Distinctions, and prostrate all Ranks, to one common Levell."

Adams, the second US president, was part of the land-owning elite guaranteed voting rights under the colonial system , had an estimated net worth of $21.5 million in modern US dollars , and owned a 40-acre estate. But skepticism of democracy wasn't an Adams-only problem. Other Founding Fathers were wary of populism and initially ensured that only members of the House of Representatives were elected by popular vote ( senators became elected by popular vote after 1913 , with the ratification of the 17th Amendment to the Constitution).