What Presidents Can And Can't Do On Day One

Throughout the 2024 campaign, Donald Trump issued promise after promise for what he was going to accomplish on "day one" should he be re-elected, including closing the border, ramping up oil drilling, pardoning participants in the January 6 insurrection, solving the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, slapping tariffs on imports, and plenty more. Trump wasn't the first presidential candidate to make big promises for his first day on the job, of course. Joe Biden and Barack Obama both had a long list of items they wanted to act on immediately and took steps to fulfill within their first hours in the Oval Office.

It's one thing to make such promises, though, and quite another to carry them out in anything like the timeline implied by calling them "day one" priorities. Presidents across the political spectrum have struggled to speedily push through their agenda, when they haven't surrendered or abandoned campaign pledges altogether. It turns out that the most powerful government on Earth is a massive and complicated behemoth, one that's not easy to steer toward a new course within 24 hours. And even the most authoritarian of presidents still isn't an unrestrained chief executive.

But there are some things a president can do to at least get their agenda started on their first day, and even a few things they can accomplish at the stroke of a pen. Here are a few of the steps a president can take on day one, and a few that they can't.

Presidents can reverse their predecessor's policies

The United States president is the chief executive of the nation. It's their responsibility and their prerogative to set the agenda for the government, so when the office changes hands from one political party to another, it's to be expected that such plans. Incoming presidents need to be able to change the government's direction to suit their policies, and there are steps they can take on day one by negating or reversing those set by their predecessor.

The executive branch falls under the president's authority, and it requires no act of Congress to enable the president to issue orders on the priorities of various departments. President Joe Biden reversed the immigration policies of President Donald Trump, and it's expected that Trump will simply switch them back when he retakes office in 2025 (per the Wall Street Journal). A similar back-and-forth occurred regarding America's participation in the Paris Climate Agreement; President Barack Obama directed America's involvement, Trump pulled the nation out, Biden re-entered the agreement, and Trump will likely withdraw again.

But some of these reversals don't amount to much more than words — aspirational goals or costless pandering, depending on how cynically you're inclined to regard politicians. Barack Obama's pledge to close the Guantanamo Bay detention center was issued within his first week in office, but eight years later, the prison remained, making Trump's decision to rescind that pledge redundant (per NPR).

Presidents can issue executive orders

The executive order — a signed directive from the Oval Office — is a tool that has come into ever-increasing use by American presidents, and one they can employ from day one. They've been both described and criticized as "instant law," according to the American Bar Association, and carry the full force of law. As edicts from the executive branch, executive orders require no approval from Congress and can only be rescinded by a sitting president. Their scope can be sweeping and controversial, to the point where Congress may opt to pass legislation complicating the order by removing funding or making it redundant.

There is no mention of executive orders in the Constitution; the authority to issue them is assumed to stem from Article II, Section I's vesting clause. Because they offer an expedient way for presidents to get their agenda rolling, they've been relied on more heavily in recent history, and they've become something that aspiring presidents consider and tout before taking office or even winning election. Upon winning, a president-elect and their team may use the transition period to draft executive orders so that they're ready to go on day one (and perhaps be written so as to head off potential controversy).

Presidents can fire (some) people

Before he was president and after he was a washed-up businessman, Donald Trump was a reality TV star who traded heavily on the catchphrase: "You're fired." In the White House, he put his catchphrase to use in several controversial moves, notably the firing of FBI director James Comey. Towards the end of his first term, Trump was making moves to ease the path for federal officials to be summarily dismissed, but the president already has the power to fire people on day one — at least, some people.

The Constitution doesn't explicitly invest a president with the right to fire people. However, there is a congressional decision from 1789 and a series of court rulings going back to 1926 that have helped establish precedent for the removal of federal workers under the executive branch, or anyone that the president had a hand in appointing, although an exception is made in the latter case for federal judges.

That exception has gone uncontested, but there has been considerable controversy since 1926 as to the scope of the president's firing powers. The 1933 Humphrey's Executor vs. United States decision (per the New York Law Journal) drew a sharp distinction between executive branch workers and members of agencies appointed by the president (but engaged in non-executive work), and later decisions have continued the debate over whether independent agencies or figures like special prosecutors are subject to presidential dismissal.

Presidents can pardon federal crimes (but not state ones)

A strange ritual of American political life involves the president pardoning a turkey every Thanksgiving. It's not a particularly ancient custom, and it's not one that's saved that many turkeys from the roasting pan. But it does make light of a very real presidential power, one they can employ from the moment they're sworn in: the pardoning of federal offenses.

The pardon power is one that is spelled out in the Constitution in fairly sweeping terms. Per Article II, Section 2 (via Brookings), "The President ... shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment." A presidential pardon can provide sweeping amnesty for large groups of people the president has no direct involvement with or even any knowledge of. They can be pre-emptive, removing the threat of prosecution from those anticipating it, and they can act as commutations of existing convictions.

But, aside from the exception made in the Constitution for impeachment, there are well-established limits to the president's pardon power. Perhaps the most solid of these is the proviso that the president can only issue pardons for federal crimes. They have no say at the state level, and even at the federal level, the president's reach only extends to criminal matters; they cannot pardon civil convictions. A convicted person pardoned by the president can refuse it. Even if they accept it, they're still required to confirm their conviction, suffer the consequences of that conviction on their future employment, and are still liable for damages owed to a third party.

Presidents can't make laws

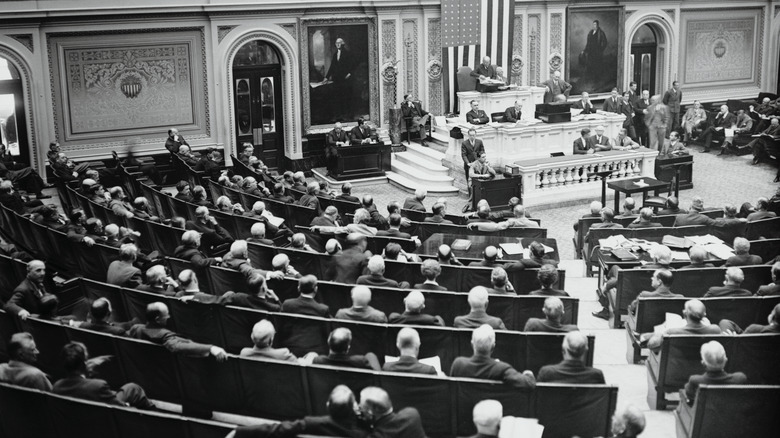

The phrase "separation of powers" doesn't occur in the U.S. Constitution, but the concept is one of the most celebrated and discussed aspects of the American system of government. In their determination to avoid what they saw as the deficiencies of the British crown, the framers of the Constitution drew sharp lines between the three branches of government. They gave a prescribed role to each while trying to keep the prerogatives of one from the others. To that end, it's clearly established that lawmaking powers rest with Congress, not the president, who cannot under any circumstances make legislation.

As chief executive, the president has some role to play in lawmaking; they can choose to sign or veto a bill presented to them by Congress. But Congress retains the power to overturn a veto, and while executive orders have great legal weight, the president can't use those orders to seize control of the lawmaking process.

Article II, Section 3 of the Constitution charges the president with "faithfully executing" the laws of the land, seemingly investing them with sweeping scope to interpret what the law intends as they enforce it (per the National Constitution Center). But within that is the presumed stipulation that a president — or those working for them — can't violate or suspend laws, as that wouldn't represent faithful enforcement. But what if a law is considered by a president to be unconstitutional or to represent an infringement on the executive prerogative? Those questions remain active debates within American law.

Presidents can't (yet) decide how to spend money

Besides holding all legislative power, Congress also holds the power of the purse in the American system. Per the Constitutional Center, it's explicitly stated that no public money held by the federal government will be spent except as directed by Congress. This is known as the appropriations clause, and it means that a president can't decide on a whim to pour money into a pet project or a foreign operation. Certain exceptional circumstances might allow for unauthorized expenditures — President Abraham Lincoln spent $2 million at the outbreak of the Civil War without congressional approval — but this separation of powers has traditionally held firm.

But some presidents have pushed back through attempted impoundment; the refusal to spend money granted in legislation. Longstanding precedent says that the power of the purse extends to a mandate to spend the full amount allotted to agencies and programs by Congress. In other words, a president shouldn't be able to unilaterally refuse to spend assigned funds, an argument regularly upheld by the courts.

President Richard Nixon tested the impoundment issue more often and more aggressively than any of his predecessors, and he was repeatedly rebuffed throughout his time in office. Partly in response to Nixon's efforts and partly to facilitate a public mechanism for presidents to request changes to spending, Congress passed the Impoundment Control Act of 1974, creating a 45-day window for presidents to defer spending after putting in a request to Congress.

Presidents cannot invalidate any part of the Constitution

Suppose a newly elected president wanted to revoke a certain right guaranteed by the Constitution, an act that they had previously made into a campaign pledge, and that they were preparing an executive order to pursue that goal. That may play well to the voting base for that president, but it's not something they can do on day one or at any other time.

Neither the president nor Congress can overturn any part of the Constitution by decree or even by the regular legislative process. To amend the Constitution requires a two-thirds majority vote in both houses of Congress, followed by ratification by three-fifths of the states. Alternatively, two-thirds of the states could call for a constitutional convention to propose amendments. It's an incredibly hard bar to clear, and there have been vocal critics of how much effort is needed to amend the Constitution. But the difficulty of the process has at times acted as a safeguard to civil rights.

If a president were serious about amending the Constitution, they could play a role in the process. In the past, they have acted as promoters of proposed amendments. But they have no prescribed role in writing or ratifying amendments, and they have no ability to veto proposed amendments that have been ratified.

Presidents can't fill their Cabinet without Congress

The president assumes all powers and responsibilities from the moment they're sworn in on January 20, and that includes the appointment of cabinet secretaries to run the executive branch. But cabinet officials aren't elected and they don't automatically come into power along with their boss, as becoming a secretary requires confirmation by the Senate. Adding in other executive branch officials requiring confirmation yields over 1,300 such roles (per the Center for Presidential Transition), and the Senate can be languid in getting them all knocked out: The average number of days it takes for the Senate to confirm presidential appointments increased steadily from the Reagan to the Biden administrations.

It's possible for the Senate to expedite confirmations; they aren't always slow and sometimes rush to get a president their nominees. But the body has other responsibilities and priorities that take up time. Senators may also have serious concerns about the fitness of a nominee — or at least, they may say so and hold up the confirmation in order to get concessions from the executive on other issues.

Historically, the Senate has been very deferential to the presidency on the matter of cabinet appointments, and only 25 nominees have ever failed to be confirmed. But if a president were dead-set on a rejected candidate, there are workarounds. The recess appointment clause lets a president fill vacancies on a temporary basis if the Senate is in recess, although those appointments only last until the end of the next legislative session.

Presidents can't unilaterally and immediately affect inflation

Inflation may well have been the driving force of elections worldwide in 2024, with the lingering inflation from the COVID-19 pandemic driving massive swings against incumbent parties on both the left and right. Historically, when economic factors like price rises spiral out of control, the public inevitably turns their ire towards the authorities.

The U.S. was not immune to such electoral swings, but you really can't pin inflation on the president. Economic policies by the administration will certainly impact the economy, but geopolitical forces around the world with similar or greater influence are out of a president's hands. In the case of inflation after the COVID-19 pandemic, a global contagion wreaked havoc on supply lines, something no individual could be expected to manage.

But if a president can't be blamed for inflation, they're also not able to do much about it in a short time frame, let alone their first day on the job. For a start, there is no insta-fix for such a massively complex and fluid issue, and the president doesn't have the authority to simply lower prices across the board. More authoritative than the president on such matters is the Federal Reserve, which has long been independent from the executive branch with matters such as the raising and lowering of interest rates.