Things Harriet Got Wrong About Harriet Tubman's Life

The United States is supposed to be the land of the free. Yet, as anyone who knows anything about American history will tell you, this was never the case. America has often failed at the "everyone is free and equal" thing.

If there is any silver lining to America's messed-up history, it's that it has given rise to some of the world's most remarkable figures. Among those individuals, looming large as the very embodiment of some of humanity's most beautiful and inspiring traits, is the legendary Harriet Tubman. Suffragette, Union spy, and advocate for the poor, Tubman is best remembered as a conductor on the Underground Railroad.

Despite being a household name and deeply important to American history, 2019's Harriet marks the first time her story had ever been told in a feature film. The film peels away the matronly and somewhat innocuous depiction of Tubman most often presented, but while great care was taken to give audiences the real Tubman, claws and all, a few creative liberties were taken, both to better illustrate the world she existed in and distill the values she stood for. For those looking to separate fact from fiction, here are some of the things Harriet got wrong about Harriet Tubman's life.

Harriet Tubman never adopted a "free name"

When Harriet opens, we are introduced to a young woman named "Minty," short for Araminta. Fiery and fearless, it quickly becomes apparent that this is the protagonist of the film, the woman who will eventually become known as Harriet Tubman. Unsurprisingly, Minty's first major action in the film is escaping her master's plantation. When she ends the harrowing journey, arriving in Pennsylvania as a free woman, she marks the occasion, as many freed slaves did, by adopting a new name: Harriet, the first name of her mother, and Tubman, the surname of her husband whom she had to leave behind.

The story presented by the film works on multiple levels, vivifying Tubman's commitment to her family –- something which would guide much of her life -– introducing audiences to William Still, a black abolitionist and colleague of Tubman's, who records the name change, and demonstrating an important ritual carried out by many former slaves, later being revived by activists such as Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X. However, the powerful scene never actually happened. While Tubman and Still would eventually work closely together, their relationship likely began later after Tubman had formally become a conductor on the Underground Railroad. Additionally, while the exact date and reason are uncertain, the Harriet Tubman Historical Society says Minty was already going by Harriet Tubman by the time she escaped to freedom, most likely taking her husband's name at the time they were married and her mother's soon after.

John Tubman was less than supportive of Harriet's escape

At the beginning of Harriet, we learn Tubman is married to a man named John. The first conflict of the film arises when the couple approach Tubman's master, Edward Brodess, with papers claiming Tubman and her family were freed in Edward's father's will. Edward proceeds to tear up the document, bans John from seeing his wife, and sets in motion the sequence of events leading up to Tubman's escape. In the film, when Tubman realizes she need to flee, John is supportive of her difficult decision, and willing to cover for her; by that point, John has already been shown to be a dutiful and caring partner, even willing to risk his own freedom so he and his wife might raise a family together outside of bondage.

Little is known about John Tubman, or his five-year marriage to Harriet. In an early biography about Harriet Tubman, written by Sarah Hopkins Bradford, John is painted in a less-than flattering light, condescending and dismissive of his wife, even personally capturing her during an attempted escape. Later biographers, like Kate Clifford Larson, have challenged Bradford's depiction claiming him instead to be a love-struck and devoted man who may have even been saving to buy his wife's freedom. Whoever John was, and however he and Harriet's marriage played out, the truth is he was never supportive of her decision to escape, according to Smithsonian. In reality, while John may or may not have thwarted previous attempts to escape, he did in fact threaten to turn Harriet in, likely fearful his involvement in her escape would jeopardize his own freedom and livelihood.

John Tubman was not the first person Harriet went back for

One very strong takeaway from Harriet is just how much family meant to Tubman and how much she was willing to risk in order to ensure their comfort and safety. However, in service to an early subplot concerning Tubman's first marriage, a critical example of Harriet's devotion to family is stricken from the film.

In a famous Tubman quote from her 1869 biography by Sarah Hopkins Bedford, she laments: "I was free; but there was no one to welcome me to the land of freedom ... my home after all, was down in Maryland; because my father, my mother, my brothers, and sisters, and friends were there." A variation of the quote is delivered in Harriet around the time she arrives in Pennsylvania, except there is an explicitly expressed yearning for her husband John. This yearning prompts Harriet to leave the relative safety and comfort of her new life, ultimately beginning her role as a conductor on the Underground Railroad.

But while Tubman did eventually go back for John, prompting some variation of the events that follow in the film, the Harriet Tubman Historical Society says her first return was actually to save her niece and her niece's two children from being sold further south. Tubman's first rescue was a resounding success, and fortified her determination to free more and more people. By the time Harriet conducted her last mission, at the onset of the Civil War, nearly all of her family had been successfully freed.

Harriet Tubman's last mission was an attempt to save her sister

A tenacious woman of great instincts and quick wit, failure was a bit of an unknown for Tubman. In her time working with the Underground Railroad, Tubman famously rescued 70 individuals from slavery, doing so without ever losing a "passenger." Most of Tubman's family were among those she managed to rescue, including her elderly parents, in what was likely the most challenging mission she ever attempted. The improbable and harrowing circumstances surrounding her parents' rescue are likely what prompted their inclusion in the film, but while they make a fine cinematic climax, the decision to not include what really happened skips over one of the most important and heartbreaking moments in Tubman's long life.

In December of 1860, on the eve of the Civil War, Tubman returned to Maryland to make yet another attempt at freeing her sister Rachel from the Brodess estate. Over the previous decade, Tubman had made several attempts to free her sister, only to meet opposition each time. Smithsonian says that as depicted in the film, Rachel would ultimately die still enslaved, unlike the film however, Tubman did not become aware of her sister's passing until this final rescue mission. Even more tragically, once learning of her sister's death on her final mission, Tubman was ultimately unable to locate Rachel's children, returning instead with a family and their infant child. Understandably, the failure to free her sister would haunt Tubman for the rest of her life, a trauma made greater by the fact that she and Rachel had watched helplessly as children as their three older sisters were sold away, never to be heard from again, as the Brodess fortune began to crumble.

Harriet Tubman was never told directly that she'd be sold

Among Kasi Lemmons' expressed goals in creating Harriet was a desire to fully realize the lesser considered elements of the world in which Harriet Tubman lived. One such element that is well-known to historians but not always addressed in films is the degree to which slavery contributed to the livelihood of individual families. Not long into Harriet, we learn that the Brodess estate is in great financial trouble, and that the family must weigh the option of selling some of their slaves or risk losing their property altogether. When he inherits the estate from his late father, Gideon Brodess makes the decision to sell Minty (Tubman) though he has long favored her (the implication of which is decidedly sinister).

The plot line develops Minty and Gideon's relationship, and introduces the cat and mouse narrative that is constant in Tubman's life. But while the Harriet Tubman Historical Society reports the Brodess' financial woes were entirely real, there's no reason to believe that Tubman was tipped off, let alone directly told about about the family's plan to sell her further south. After the death of her owner Edward Brodess made it clear that her life would once again most likely be upset by change, Tubman would commit herself to escape, altering the course of her life, as well as that of American history.

Harriet Tubman did have 'visions,' but they weren't her true gift

At the age of 12, while intervening in a conflict between a slave and their master, Tubman was struck in the skull with a weight, fracturing her skull and giving her permanent brain damage. A deeply religious person, when Tubman began experiencing hallucinations as a result of her injury, she attributed them to God, interpreting them as warnings. In Harriet, Tubman's visions are treated as a completely real ability possessed by Tubman, a gift of supernatural foresight which she uses to evade slave catchers and plot her rescue missions. In reality, Tubman's injury, despite her reverent attitude towards it, probably did more harm than good, and certainly wasn't what carried her along on her many dangerous journeys.

According to the Harriet Tubman Historical Society, once she was old enough to work, Tubman did everything in her power to avoid domestic chores and being around white women. Working outside in the fields was harsh and labor-intensive, but in her years spent outdoors, Tubman developed an intimate connection with the natural world. The Brodess family also frequently lent and rented their slaves out to neighbors and paying strangers within the area, further expanding Tubman's awareness of the topography of Maryland. Contemporaries of Tubman, as well as present day historians, often marvel at the immense feats Tubman carried out, first by finding her own way to freedom, and then by aiding the escape of many others. But while Tubman herself would undoubtedly claim her abilities were aided by her celestial visions, her knowledge and instincts were probably much more helpful in her long and amazing career as an Underground Railroad conductor.

Gideon Brodess was actually named Johnathan and was entirely fictionalized

While Harriet and her mother were slaves for the Brodess family in real life, there is no record of the family having a child by the name of Gideon. They did have a son named Johnathan, though there is little historical information about him beyond that. Many other facts about the family –- from the patriarch's death to their eventual decline in status and wealth necessitating them to sell off their slaves, starting with Harriet's sisters -– are true, though no figure in the family matters to the film more than the fictionalized Gideon. And while the real life son may have had some interactions with Harriet, he was not a major factor in her life in the way that his film counterpart is.

Gideon is arguably the film's avatar for the sins of slavery distilled into one person. He is horrible to Harriet and her family -– an early scene shows Gideon sees Harriet as nothing more than a piece of property, comparing her to owning a pig. Once Harriet escapes, it is Gideon who pursues her endlessly, obsessed with salvaging what is –in his mind — rightfully his. Like many of the characters created for the film, Gideon serves an important purpose: he pushes Harriet's story along and gives more focus to her story, which in reality was broader and more complicated (and unfortunately vague) than the confines of a film narrative allow for.

Marie Buchanon was also created for the film, though it's likely there were women like her

In the film, William Still (Leslie Odom Jr.) takes Harriet directly from the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society to the home of Marie Buchanon (Janelle Monáe). While she runs a house for newly-freed women like Harriet, Marie herself was born and raised a free woman in Philadelphia. As such, Marie is a successful business owner. The home she operates provides shelter to those looking for a new life, but she also helps them find paying jobs and helps to create a community for those braving the new world alone. While screenwriter Gregory Allen Howard says it's highly likely that women like Marie Buchanon existed, and may have even helped runaway slaves like Harriet, the Marie Buchanon character and the interactions she has with Harriet are entirely fictionalized.

In reality, little is known about how Tubman lived once she arrived in Pennsylvania. Much of her history revolves around her journey and experiences with the Underground Railroad, but where she lived or who exactly helped her when she first reached freedom is less clear. It's likely Marie Buchanon is a cipher for someone who may have existed and been able to help Tubman, alone and afraid, find her footing. Marie is everything Harriet wants to be: poised, confident, and very sure that no person should ever belong to anyone but themselves. Marie's support helps validate Harriet's decision to go back to Maryland, and Marie's gun gives her the means to do so with some protection. Regardless of its accuracy, it's an effective storytelling choice that helps flesh out the world around Harriet while giving her a worthy ally.

Bigger Long was also made up, but black slave catchers did exist

In the film, Harriet's first trip back to the farm sees her freeing not only her own brothers, but several others who have heard of her return and are eager to seek freedom themselves. In total, Harriet escorts nine people back to Pennsylvania, but not without getting noticed along the way. Gideon, furious at the thought of losing even more slaves, hires a local bounty hunter named Bigger Long, a black man who hunts and captures runaway slaves for a hefty fee. While Slate reports it's been widely speculated that black bounty hunters like Bigger Long likely existed, there's no historical record of anyone by that name operating in Maryland at the time of Tubman's escape.

Bounty hunters like Bigger Long, often referred to as "Slave Catchers" were often simply mercenaries were hired by wealthy slave owners to reclaim what was seen as "stolen property" whenever a slave would run away. At various points in history these figures were actually law enforcement officials whose official duties included tracking and returning fugitive slaves. In the film, Bigger Long is depicted as using a wolf-like dog to help track the slaves — in reality, many mercenaries used bloodhounds and other highly-trained dogs in their own pursuits. There are some records that seem to indicate that black head hunters like Bigger Long may have existed in Ohio and Pennsylvania, but the names are far and few between.

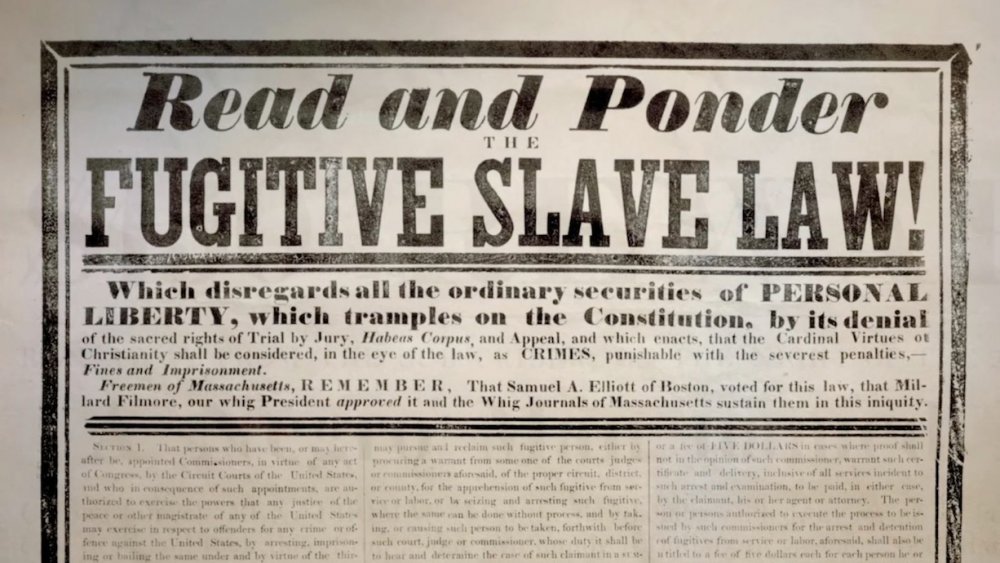

The Fugitive Slave Act was closer to the time of Harriet Tubman's escape than the movie depicts

By the time the Fugitive Slave Act is passed in the film, Harriet has already successfully completed so many trips back and forth between Maryland and Pennsylvania that she's become one of the most prolific (and successful) conductors the Underground Railroad has ever seen. She's so effective, she's even earned a reputation and imposed identity: posters all over the South search for the man named Moses, the one setting all of the slaves free. While it makes for an impressive movie montage, in reality the Harriet Tubman Historical Society says she would have only completed one, maybe two trips before the Fugitive Slave Act was enacted in 1850.

As is shown in the film, the biggest impact of the Act was the distance slaves would have to travel in order to obtain freedom. Prior to its passing, slaves only needed to reach states where slavery was already abolished (such as the safe-haven that was Pennsylvania). The Fugitive Slave Act is alternatively known as the Compromise of 1850, as it sought to appease the slave owners of the South by allowing them to recapture their "stolen property" no matter where in the US it may have ended up. As a result, those seeking asylum were forced to push further North, all the way to Canada. This extended Tubman's journey by hundreds of miles, increasing the risk of capture, but also increasing the likelihood that something else could go wrong on the journey. Slaves navigated a complicated landscape full of thick forests, rushing rivers, and a scarcity of food. A longer trip meant more risks, and potential for complications as a result of food or water shortages along the way. As is shown in the film, Harriet is determined in the face of such challenges. Though it would have cut Harriet's time in Pennsylvania down to mere minutes, it may have made her harrowing journeys all the more impressive had the film stuck to the original timeline.