The Messed Up Truth Of The Nobel Prize

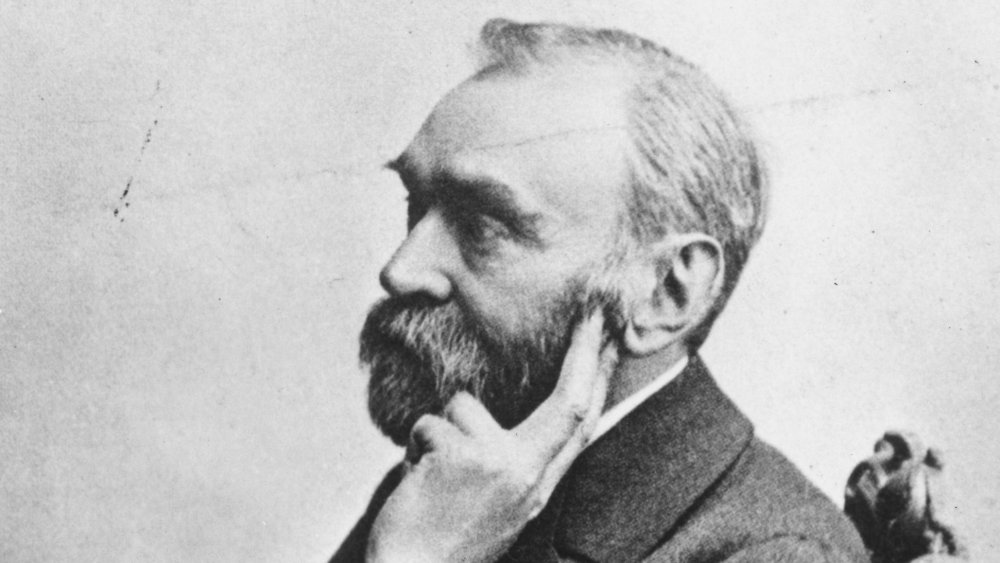

If the prestige of an award is defined by how famous it is, perhaps only the Academy Awards can hold a candle to the Nobel Prize. As Live Science records, the esteemed science, literature, and peace prizes were founded by and named after Alfred Bernhard Nobel, the son of a weapon inventor and an explosives manufacturer himself. This, in itself, creates an odd juxtaposition between the noble purpose of the Nobel Prize and its murky origins, but it's far from the only strange thing about the award. Throughout its history, the Nobel Prize has been plagued by controversies and unfortunate decisions, and especially when you look at it through the lens of hindsight, some of the darker stains in the medal that bear old Alfred's image can seem downright vile.

Today, we'll dive deep in some of the stranger stories that have added to the award's occasionally less-than-exemplary reputation. Come, let's take a look at the messed-up truth of the Nobel Prize.

The Nobel Prize is financed with blood money

As Live Science tells us, Alfred Nobel's decision to set up the Nobel Prizes came from a place of personal terror. Nobel's claim to fame was explosives — particularly his biggest invention, a little something called dynamite. As dynamite's explosive power was inevitably appropriated by the military and explosives and "dynamite cannons" started killing thousands of people in conflicts, Nobel's (literally) groundbreaking invention started getting a murderous reputation and his name started turning to ash in people's mouths.

It's unclear whether Nobel personally approved of his invention's military use, but he was reputedly something of a pacifist and seems to have been unaware of the bad name all the dynamite deaths were giving him. He found it out the hard way in 1888, when his brother Ludvig died. For whatever reason, several newspapers around the world accidentally printed Alfred's obituary instead of Ludvig's, and the poor rich explosives mogul was deeply shocked when the press spewed hate on him for profiting from people's deaths. One French paper even gleefully reported: "The merchant of death is dead." Horrified and desperate to improve his legacy, Nobel wrote a will that allocated most of his considerable wealth into founding the Nobel Prize organization.

The Nobel Prize and sexism

Jocelyn Bell Burnell, as Encyclopedia Britannica lets us know, is a pretty awesome astronomer who was instrumental in discovering pulsars. When said discovery was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1974, however, Bell Burnell's name was nowhere to be seen, and the prize was instead awarded to two of her male colleagues. This is not an isolated incident. In fact, according to MIT Technology Review the Nobel Prizes suffer from a deep gender bias. From 1901 to 2018, there have been 112 Nobel Prizes for Physics awarded — and the only female laureates have been Marie Curie (1903), Maria Goeppert Mayer (1963), and Donna Strickland (2018). The awards for economics, chemistry, and medicine are hardly better. In total, only 21 of 688 science Nobel winners are women.

This is where some may ask: "But how can we know that this is because of sexism and not because there have been so few women who are good at science?" Turns out, we know it ... thanks to women who are good at science. Liselotte Jauffred and his team at the University of Copenhagen have analyzed the gender ratios of Nobel-worthy scientific fields and compared them to gender ratios of Nobel laureates, and there's a clear disparity. They do note, however, that this is not necessarily because the Nobel committee just brushes off female candidates. It may just be because of the "many biases and hindrances" women face in their fields. That's... actually even more depressing.

The Nobel Prize is allegedly actively disturbing science

The Nobel Prize might be the ultimate reward for a scientist, but as the Guardian's Science Editor Robin McKie points out, the prize has fallen near-irreparably out of sync with science as it exists today. According to McKie, modern science doesn't really have the kind of great, individual discoverers that Nobel laureates are generally seen as. Instead, great discoveries are products of collaboration, which means that a system that actively rewards personal achievements (and thus promotes competition) is downright dangerous. This has led to some pretty harsh criticism from the scientific community. As cosmologist Brian Keating puts it: "The Nobel Prizes have strayed far from the vision their founder had for them, and they badly need to be reorganized. They reward an outdated version of science."

The Atlantic agrees with the sentiment, and notes that Nobel Prizes constantly draw criticism of their "anachronistic" methods that "distort" the very nature of science and ignore tons of important scientists in favor of a select, happy few. For instance, the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics went to Rainer Weiss, Kip Thorne, and Barry Barish of LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) for discovering gravitational waves. It also completely ignored the work of hundreds of researchers who were instrumental to the project's success.

The Nobel Prize winners who didn't quite deserve it

Prizes have one winner and hordes of losers. That's why it's important to get the winner as right as possible, and the Nobel Prizes' track record on that is unfortunately somewhat dubious. As CNBC tells us, the list of controversial Nobel laureates is as long as your arm. There's Fritz Haber, the 1918 Nobel Prize in Chemistry winner, whose grand invention (industrial production of ammonia) was apparently great enough to forget that he's also the guy behind WWI's infamous chlorine gas. António Egas Moniz, the 1949 physiology/medicine Nobel winner, invented a little procedure called lobotomy, which is not a good look in hindsight.

And then there are the Peace Prizes. In 1973, there was U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who had Hanoi bombed while he was negotiating the ceasefire he won the award for. 1994 saw Palestine's Yasser Arafat and Israel's Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres share the award, which was weird not only because they completely failed to end the Israel-Palestine conflict, but also because, as Time notes, Arafat was hardly a peaceful and diplomatic leader.

One of the most baffling Nobel decisions was President Barack Obama's Peace Prize in 2009. Time writes that the Nobel committee itself admitted Obama had few concrete peace-themed achievements in his pocket, instead arguing that the prize was for peace "efforts." As the Independent reports, even the president himself has admitted that he has zero idea what the prize was for.

Adolf Hitler, Nobel Peace Prize nominee

Who do you think would never, ever in a billion years be nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize? Adolf Hitler. Who, nevertheless, was a proud Nobel Peace Prize nominee in 1939? Yep — Hitler.

As Quartz tells us, the thing to remember here is that there are many, many people who can nominate folks for a Nobel Prize. Among them was Swedish parliament member Erik Gottfrid Christian Brandt, who thought it would be funny to nominate the Führer — who, as everyone at that point knew, was hardly a man of peace — for the prestigious Peace Prize. Brandt laid it thick on his recommendation letter, with phrases like "a God-given fighter for peace" who would "pacify Europe, and possibly the whole world." His intentions were honorable, as he was a staunch anti-fascist who intended to use the letter to point out Hitler's terrifying nature as the "#1 enemy of peace." Unfortunately, sarcasm works on Nobel nomination letters even worse than it does on social media. Brandt was branded a fascist, and his recommendation created outrage and got him banned from several lecturing gigs.

Hitler obviously didn't end up winning the prize, though ironically, there's a good chance he'd have turned it down. The dictator disliked the Nobels ever since his vocal critic Carl von Ossietzky bagged the Peace Prize in 1935. In retaliation, the Führer set up his own Nazi version of the Prizes and forbade German citizens from ever accepting a Nobel.

Nobel Prize? No, thank you

Regardless of its problems, the Nobel Prize is one of the most prestigious awards out there. That's why it must be doubly embarrassing when a recipient who's being informed of the honor just looks at you blankly and says: "A Nobel? Ugh. No, thank you." This has actually played out not just once, but two times. According to the Nobel Prize website, the first person to refuse a Nobel was Jean-Paul Sartre, who politely declined his 1964 Nobel Prize in Literature. His motive was that he never accepted any "official distinctions" because he felt this would "institutionalize" him and "limit the impact of his writing." He didn't intend to cause a scandal, though, and was sorry that he did.

In 1973, North Vietnam's Le Duc Tho joined Sartre in the exclusive Nobel Refusal Club. As Time tells us, Tho was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize jointly with the U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger for their efforts in ending the Vietnam War, but when the U.S. alone embraced the trophy, it became evident Tho wasn't happy to join the celebration. The reason he gave was that he couldn't accept a Peace Prize when war still raged, and though he said he might reconsider in a more peaceful time, he never did. It could be argued this was wise, as critics have pointed out that Tho and Kissinger (who happily accepted his prize) also played a part in "creating" the war in the first place.

The Nobel Prize-winning formula that helped crash the economy

In 1997, the Nobel Prize for Economic Sciences went to Myron Scholes and Robert Merton who, along with their late colleague Fischer Black, managed to create a "new method to determine the value of derivatives." As the Guardian reports, the practical use for this tongue-twisting description was a "holy grail for investors." According to BBC, the Black-Scholes formula could predict the market, enabling wily investors to trade derivatives (complicated financial options that are essentially informed betting on investments) at a lightning pace, which sent the market into feeding frenzy.

The equation itself was quite functional. Unfortunately, the people using it got a little... overexcited. By 2007, the global derivatives trade was an absurd quadrillion (thousand million million) dollars, and hedge funds and banks started relying on the equation more and more. However, they didn't know when to stop. As the subprime mortgage market started showing signs of rottenness that same year, the process turned on itself — trading on derivatives suddenly "became the Black Hole equation, sucking money out of the universe in an unending stream." And that's how you get a global financial market collapse big enough to warrant its own entry in Encyclopedia Britannica.

The alleged AstraZeneca Nobel Prize scandal

In 2008, a fresh Nobel laureate called Harald zur Hausen sparked no small amount of controversy. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, zur Hausen himself is a fairly innocuous choice for the recipient of the Nobel Prize for Medicine. He's a German virologist who discovered the link between the human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer, and shared the prize with two other scientists who discovered HIV. Terrifying but useful knowledge, all in all.

However, as Scientific American notes, many people started wondering about the fact that a pharmaceutical juggernaut called AstraZeneca had dibs on a HPV vaccine, and would turn a nice profit if the "HPV scientist" won a Nobel (and the prestige and publicity that automatically follow). As Science Mag reports, people also suspected that AstraZeneca's desire to get to those sweet, sweet patent royalty bucks may have motivated the company's recently announced collaboration with the Nobel foundation's website and the Nobel Media company to produce content and promote the prize. Interestingly, an AstraZeneca board member also sat on the committee that awarded zur Hausen the prize.

Still, it appears that the whole thing amounted to little more than allegations and "probings" by officials, seeing as the collaboration between the company and Nobel Prize Inspiration Initiative continues.

The 2018 Nobel Prize in Literature scandal

As the Guardian reports, the year 2018 saw one of the most public scandals surrounding the Swedish Academy (the institute that awards the Nobel Prize for Literature) when Jean-Claude Arnault, husband of academy member Katarina Frostenson, became entangled in a sexual assault scandal. No less than eight women filed "formal complaints" against Arnault, who was eventually sentenced to two years in prison. However, the troubles he had caused to the Swedish Academy had only started. It transpired that the academy had partially financed a culture club run by Arnault and Frostenson, which started drawing accusations of conflict of interest. It didn't exactly help that Nobel winners are a popular subject of betting, and Arnault was reportedly in the habit of leaking the names of Nobel literature laureates before they were announced.

The academy fell into deep disarray over how to handle the situation, and as the dust cleared, seven of the 18 academy members — including Arnault's wife — decided to walk away. The 2018 Nobel Prize in Literature was cancelled, though it was eventually awarded to Olga Tokarczuk.

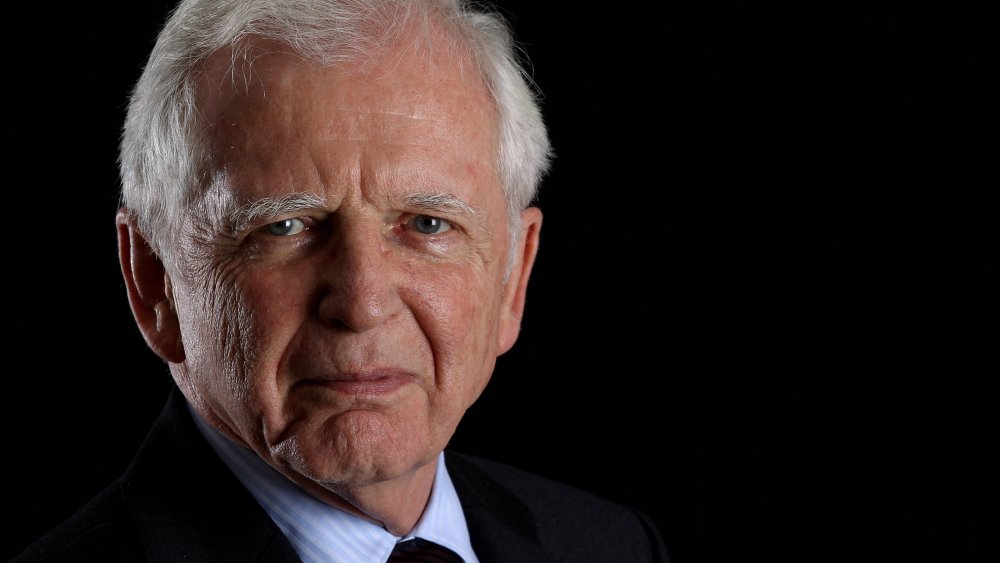

The Nobel Prize in Literature creates controversy... again

Expectations for the 2019 Nobel Prize in literature were high after the 2018 Nobel Prize was postponed thanks to a particularly nasty scandal involving the husband of a member of the Swedish Academy, as Slate reports. The literature prize is hardly the most offensive one on the menu, so one scandal was already an aberration from the norm. Imagine then that in 2019, the academy managed to jump right back in the proverbial pigsty by awarding the Prize to Peter Handke.

Handke is an Austrian writer and firebrand who's "infamous for his Serbian nationalist sympathies," and doesn't hesitate to show his feelings. In 1996, he courted significant controversy with two essays that blamed the media for presenting Serbs as the "evil" party in the Yugoslav Wars and Muslims "as the usual good guy." At this point, it's probably worth pointing out that as History notes, the Yugoslav Wars involved an incident called the "Bosnian Genocide," where Serb forces killed an estimated 100,000 Croatian civilians and Bosnian Muslims. Handke even gave a speech at the funeral of Serbia's President Slobodan Milošević (Nickname: "Butcher of the Balkans"), who had died before his trial for genocide and war crimes could wrap up. Handke handwaved his decision to do this by saying Milošević was a "tragic human being" and that he himself was merely "a writer and not a judge."

Nobel Prize committee members received free trips to China

The process behind the Nobel Prizes is a fairly secretive one, so when Swedish prosecutors start launching investigations into allegations of bribery, it's probably fair to guess that some eyebrows were raised in a highly scientific manner. According to the Local, in 2008 the officials became interested in the affairs of three Nobel committees when it transpired that their members had received free trips to China ... from the Chinese government. The trips, which took place in 2006 and 2008 and involved a total of five committee members, were all-inclusive affairs, with hotels, flights, and food all paid for.

What makes this particular situation so strange is that even the committee members themselves realized and fully admitted that the whole deal was kind of iffy. According to Bertil Fredholm, head of the Karolinska Institutet Nobel Committee (which is in charge of the Nobel Prize for Medicine) and a participant on one trip, "It's a borderline case, but we discussed it ahead of time, but it is borderline." Sven Lidin, member of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry, also went to China despite expressing even more doubts: "Just the fact that you're asking about this makes me think that it's possible that it would have been a better idea to pay for it from Sweden."

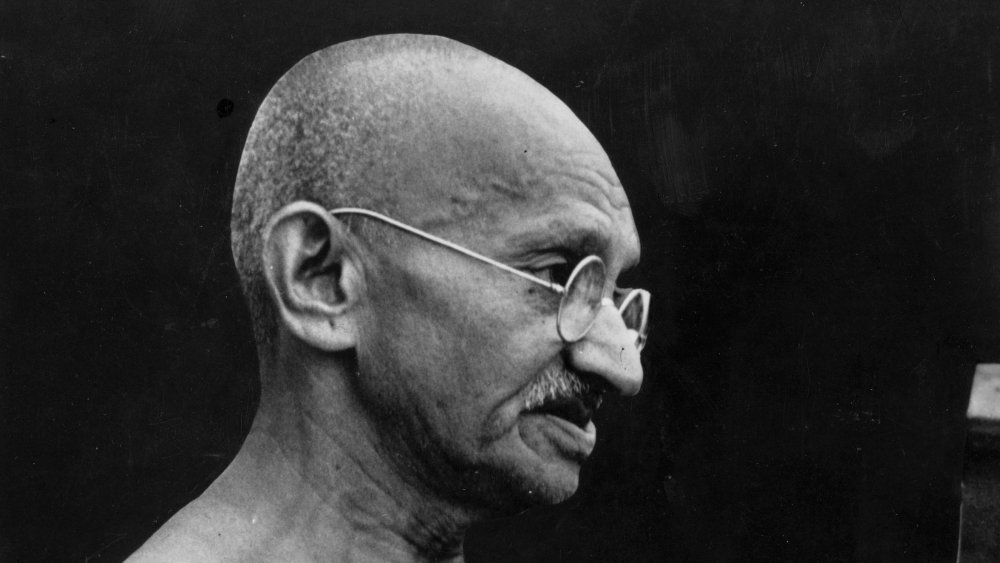

Obvious Nobel Prize winners who somehow never won

"Nobel laureate" is arguably the greatest honor that can be bestowed for an expert of physics, chemistry, physiology/medicine, economic science, literature, or peace. However, there's a limited amount of these awards to go around, and according to National Geographic, a shocking number of people who absolutely ruled their respective Nobel-worthy fields have never been honored with one. The World Wide Web is arguably the most groundbreaking invention of the age we live in, but Tim Berners-Lee has never seen a Nobel for that. Of course, it could be argued that his creation doesn't really qualify under any of the categories, but how about juggernauts like Thomas Edison and Stephen Hawking (who, admittedly, might have won if his black hole research wasn't so highly theoretical)? What about magnificent breakthroughs such as the periodic table, or the completion of human genome, or the discovery of dark matter?

It's not just the science prizes, either. Arguably the most glaring omission from the list of Nobelists is Mahatma Gandhi, whose lack of a Nobel Prize for Peace despite his five nominations is such a sore spot that even the Nobel Prize website calls him "the missing laureate." While the Nobel committee has never disclosed their decision to repeatedly snub Gandhi, his absence proved so impactful that when the Dalai Lama received his Peace Prize in 1989, it was specifically stated that it was "in part a tribute to the memory of Mahatma Gandhi."