Why The Battle Of Iwo Jima Was Worse Than You Thought

In terms of death, casualty, and political ramifications, World War II was so much worse than World War I. With massive, catastrophic battles fought all over the world between the U.S., U.K., and Russia-led Allies and the Axis powers — represented by a coalition of Italy, Nazi Germany, and Imperial Japan — just about every nation on Earth was negatively affected in some way, and many suffered unfathomable loss. One long and arduous fight, and one of the most important battles of World War II, was the Battle of Iwo Jima.

A lot of things about World War II don't make sense, including the nature of combat during this complex battle between American and Japanese forces that lasted for more than a month and was waged toward the end of the World War II Pacific Front timeline. A lot of what happened on Iwo Jima in early 1945 remains tough to believe, but war pushes people and communities to their absolute limit, and that's what happened on this island outpost. Here's a look at some of the most chilling, saddening, and horrible details concerning the Battle of Iwo Jima.

The battlefield was small, rough, and punishing

The island of Iwo Jima wasn't some densely populated territory that was particularly culturally or socially important to Japan. Geographically, it's obscure and remote, situated in the northwestern end of the Pacific Ocean and more than 600 miles away from the Japanese capital city of Tokyo. Cut off from civilization, it wasn't populated by any cities, towns, or outposts outside of its wartime potential, as Iwo Jima was both too small for that and the terrain too punishing. Iwo Jima takes up an area of about 8 square miles, and it's made primarily out of ancient volcanic runoff. It's a rock, covered in rocky land, where little can grow, and certainly not enough to sustain life.

The value of Iwo Jima lay in where it was in 1945. It was more than 600 miles away from Japan's biggest city but also just about that exact distance away from Guam, a small island and U.S. territory in the Pacific Ocean. If the U.S. military could take control of Iwo Jima away from Japan, it would have a well-located outpost with which to keep an eye on its adversary and to stage air missions and more bombardments. It was partly a result of the island's diminutive size and rough topography that, instead of being an easy target, it became a meatgrinder during the battle to capture it.

The Battle of Iwo Jima wasn't a fair fight

Despite the relative tininess of the island of Iwo Jima, it served as the fighting spot, and ultimately the place of death, for a staggeringly high number of combatants. Waged primarily by the U.S. Marines' V Amphibious Corps, with some battalions of soldiers from the U.S. Navy, a total of about 70,000 Americans were charged with fighting on Iwo Jima in 1945. Defending the island were 22,060 Japanese troops.

Fighting lasted for 36 days, and both sides endured horrific and historic losses. The American contingent bore the deaths of 6,821 men and about 20,000 experienced a significant casualty in the form of an injury or bodily loss. In terms of death and nonfatal casualties, Iwo Jima delivered the U.S. Marines its biggest losses in history. The Japanese military presence was almost completely annihilated. Of the 22,060 troops, the vast majority of whom had been drafted into fighting, 18,844 died on Iwo Jima (a casualty rate of 85%), and a further 216 Japanese troops were detained as prisoners of war. Of the 82 members of the Marines — one of the oldest branches of the U.S. military – who received a Medal of Honor for their service in the entirety of World War II, 22 fought on Iwo Jima, along with five members of the Navy. Of that figure, 14 received their awards posthumously.

The Japanese defense was devastatingly effective

In earlier World War II battles on islands across the South Pacific, the Imperial Japanese Army met American troops head-on, engaging in immediate close-hand fighting. However, Iwo Jima was an island with unique physical features, and Imperial Japanese Army General Tadamichi Kuribayashi (pictured above) exploited those to enhance his defense.

Before U.S. units arrived on Iwo Jima, they pummeled the island with airstrikes and coastal bombardments by battleships. The assault lasted three days, down from a planned 10 because it didn't seem like the Japanese had suffered many losses. This was all part of General Kuribayashi's plan: The defenders had gone deep into the island to lay in wait.

As the troops disembarked onto Iwo Jima's beach on February 19, 1945, they struggled to literally gain a foothold. Iwo Jima is volcanic, covered in soft, hard-to-traverse ashy material formed into steep slopes. To ensure the heaviest losses, only as the beaches grew more populated by Marines did the Japanese soldiers respond, opening fire from gunner stations in the surrounding mountainous terrain. The Japanese hit the beach near sundown that day, but some Americans were able to evade the charge effectively enough to take hold of part of an island airfield, which was one of the primary goals of the invasion.

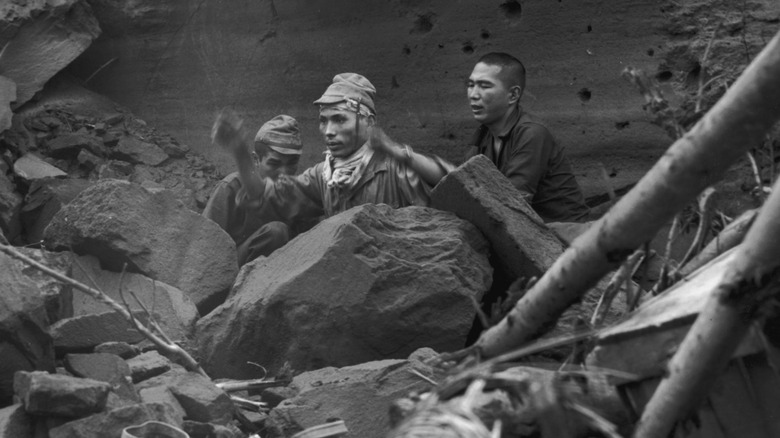

The island of Iwo Jima was covered in tunnels

Iwo Jima took up a mere 8 square miles, but that's just the surface. Below ground offered ample opportunity for the Japanese military to hide, plan, strategize, and conduct attacks in ways that remained often inscrutable to American forces. Knowing that World War II would eventually ensnare the critically located island, Imperial Japanese Army General Tadamichi Kuribayashi oversaw an ambitious plan executed by a team of engineers to line the subterranean areas of Iwo Jima with a network of secret tunnels.

Vast, complex, and difficult to track, the military built a sophisticated program of 1,500 distinct areas used as bunkers, armories, and safe rooms, all connected to each other by more than 11 miles of protected tunnels with which personnel could move freely and without detection. Not only could the Japanese have accessible stockpiles of weaponry and safe places to retreat when cornered in a surface-level battle, they could also use the underground tunnels to secretly make their way to new, weapon-fortified positions and ambush their often baffled adversaries. Once the Americans figured out the plan, however, there wasn't much possibility for escape from underground bunkers; being cornered by well-armed Americans is how many Japanese troops lost their lives on Iwo Jima.

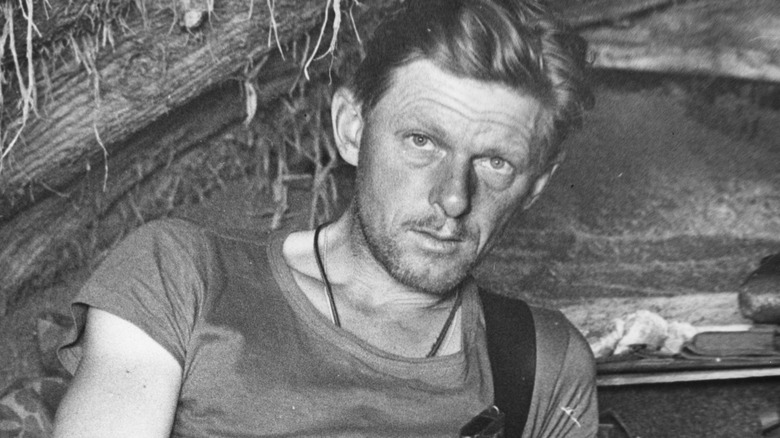

The Battle of Iwo Jima was a big test for the flamethrower

Besides providing the debut of the atomic bomb, a weapon so devastating and deadly that World War II essentially ended immediately after the U.S. dropped two of them on Japan, an important battle was won by American military forces because they had a superior weapon: a flamethrower. Machine-gun-armed Japanese troops felled scores of American soldiers in the first few days of the invasion of Iwo Jima. "As we attacked, they would just mow us down, and we would have to back off," Marine Hershel "Woody" Williams told History. Tanks didn't help the progress either, so an officer asked Hershel "Woody" Williams to be his regiment's flamethrower operator.

With four other Marines offering cover fire — of whom two died almost immediately — Williams and his flamethrower burned down in rapid succession multiple occupied Japanese fortresses and then fired into a dugout fort through an air vent, leaving no survivors. He made several runs back to the American side to refuel the gas-powered fire machine, and over the course of four hours hit all of his targets. Williams' efforts allowed the Americans to make progress on Iwo Jima, and within a few weeks, the battle was over. At war's end, President Harry Truman awarded Williams the top American military accolade, the Medal of Honor.

American forces were segregated

The Americans who fought at Iwo Jima were almost entirely Marines, and were almost exclusively white men. However, a handful of U.S. Army units participated in the Battle of Iwo Jima, including the 476th Amphibious Truck Company, which was composed of 177 Black soldiers. A vital support unit, the servicemen of the 476th drove 32-foot-long vehicles around the beaches of Iwo Jima, dodging Japanese gunfire to deliver ammunition, bombs, and reinforcements to Marines engaged in combat throughout the island. Since the U.S. military was segregated throughout World War II, no Black people in the American military could have been part of the fighting brigades on Iwo Jima. The practice didn't end until 1948, via an executive order from President Harry Truman.

Another group of non-white Americans was crucial in the drive to win the Battle of Iwo Jima. In 1942, the military brought in members of Navajo-affiliated indigenous tribes to assist in the war effort. The Navajo language is complex and different from widely used European and Asian languages, and so 29 Navajo speakers and writers used it with great effect, creating a memorized coded message system used to parlay information to the front lines. Marines who identified as Navajo participated in the Battle of Iwo Jima as code talkers. Six specialists sent and received about 800 messages during the battle, none of which were ever intercepted or decoded by the Japanese military.

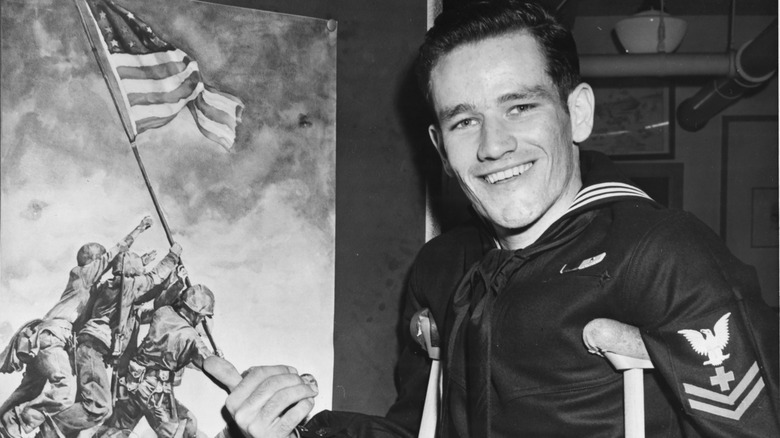

Multiple medics lost their lives while trying to save the lives of others

As the first groups of troops arrived on Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945, among their ranks were U.S. Navy and Marine-affiliated corps, including medics tasked with treating the ever-growing number of American military members. One of the first medical support staffers to hit the beach was Hospital Apprentice First Class James Ferkin Twedt. The 19-year-old was technically not a combatant, but that didn't mean he wasn't subject to gunfire. After he heard a fallen soldier call out for medical assistance, a Japanese-fired shell exploded at his feet. One was instantly and violently separated from the rest of his body, while the other was thoroughly obliterated. While largely unable to walk and losing a great deal of blood, Twedt still found the troop calling for his help and assisted others in need of medical care before he was taken off the battlefield. Twedt died two days later.

Another medic, Pharmacist's Mate Third Class Byron A. Dary, had been awarded a Silver Star for his service in the Normandy invasion in 1944 before he arrived with the USS Sanborn on Iwo Jima. He was tasked with helping to get troops onto the island and injured and deceased soldiers off, but he spent a lot of his time running into the open battlefield to grab lost and available medical supplies that had been left on the beach. During one such run, he was shot and killed by the opposing side.

The famous Battle of Iwo Jima photo has a questionable background

On February 23, 1945, Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal captured the image of five American service members raising the U.S. flag atop Iwo Jima's Mount Suribachi. One of the most famous news photos ever taken, and inspiring memorials commemorating the Battle of Iwo Jima, it won Rosenthal a Pulitzer Prize. Its origin story is complicated.

When Rosenthal got word that some Marines were scaling Mount Suribachi, he followed them. When he hit the top, Sergeant Louis Lowery, photographer for the military publication "Leatherneck," was already there and taking pictures of the Marines as they raised the U.S. flag. As American troops down below spotted it, celebratory gunfire broke out, triggering retaliatory shooting from Japanese soldiers, but as Lowery tried to find safety, he fell 50 feet and shattered his camera. As he walked down the peak, he ran into Rosenthal, now going back up with another photographer and a cinematographer. This time, he encountered another group of Marines bearing another flag — they'd been ordered to replace the initial one with this much larger, more distantly visible one. As the Marines raised the replacement flag, Rosenthal took their picture, and that's the one that made history.

The planting of the flag didn't signal the end of the Battle of Iwo Jima: The flag-staking took place just five days after combat began, and Iwo Jima wouldn't fall to the U.S. until March 26, about a month later.

The death of Sgt. William Genaust

Sgt. Bill Genaust joined the U.S. Marine Corps at age 34 in 1943, answering a call to be a combat photographer. In February 1945, he was on one of the ships that brought the first waves of Marines to Iwo Jima. After many days of capturing images and film of bloody combat for posterity, Genaust was present when the photograph of American soldiers raising the U.S. flag on Mount Suribachi was taken — he captured the moment on 16 mm motion picture film.

Genaust didn't just document the war effort; he participated in it, too. He offered to investigate one of the many hidden caves on the island that Japanese soldiers used for cover, hiding, and staging attacks. While checking to see if the area was occupied, possibly with a flashlight, he was shot and killed by the Japanese. That part of the cave system was so impenetrable with troops and firepower that the Americans retreated and exploded the cave. Genaust's remains had not been recovered as of this writing.

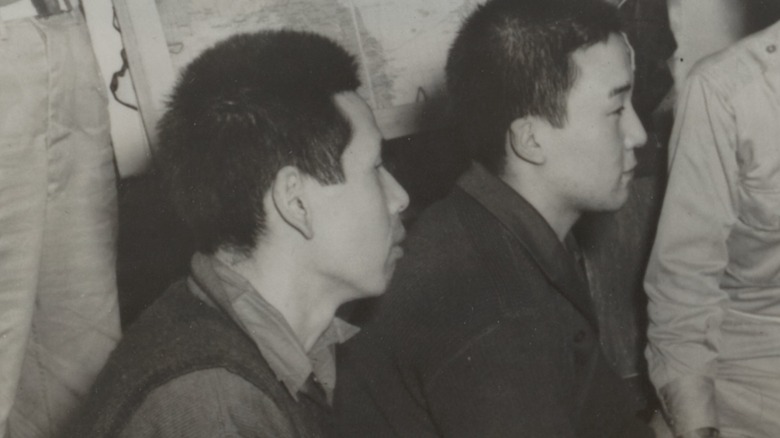

Two Japanese soldiers hid on Iwo Jima for four years

The 36-day Battle of Iwo Jima ended on March 26, 1945, with the island securely in the hands of the U.S. military. When the fighting ended, U.S. servicemen scoured the island and uncovered about 3,000 Japanese troops in caves and tunnels. Most wouldn't surrender, and many were killed or forcibly captured as prisoners of war, but two troops eluded capture throughout the remainder of the war and for many years after.

On the morning of January 9, 1949, nearly four years after the Battle of Iwo Jima (and the end of World War II), a U.S. Air Force jeep driver picked up two male Asian hitchhikers walking on a road near a Coast Guard facility. At first, officers thought the fatigues-dressed pair might be crewmen from a Chinese naval vessel working near the island. After escaping from custody, the men were found again and the island's commander put them through a lengthy interview. The two men were reported at the time to be named Yamakage Kufuku and Matsudo Linsoki, and they'd both served as machine gunners in the Imperial Japanese Navy. The surrender-resistant holdouts had survived underground without being detected, living off of the land and getting by thanks to canned food and necessities stolen from the U.S. military outposts. Kufuku and Linsoki had even moved caves on occasion, laying low near well-traveled areas.

The U.S. occupied Iwo Jima for decades after World War II

American-led forces fighting the Pacific front of World War II needed the Japanese island of Iwo Jima for its strategic value. That all came to an end in September 1945 with Japan's surrender, but Iwo Jima remained under U.S. control for decades. As part of the seriously messed up aftermath of World War II, Japan rebuilt and recovered with the American military and government maintaining a presence in the country until 1952. Diplomatic relations developed between the two countries, including the signing of a security treaty in 1951, and Japan emerged as a major global player. All the while, the U.S. continued to hold onto the small, rocky island of Iwo Jima, 600 miles away from mainland Japan. It served as the home of only some quiet U.S. military bases all the way until 1968.

The American contingent systematically returned Japanese areas it conquered during the war, beginning in 1953 with the Ryukyu Islands, and ending in June 1968 with the hand off of the inhabited Chi Chi Jima and the officially uninhabited Iwo Jima. The Japanese reclaimed authority via a flag-changing ceremony on Iwo Jima and an official government-held one in Tokyo, attended by Crown Prince Akihito and Prime Minister Eisaku Satō. The island now hosts a Japanese air base as well as a U.S. military training center, and a U.S. military cemetery.