Why World War I Was Worse Than You Thought

Dubbed the Great War and the war to end all wars (first idealistically and then ironically, given that it did no such thing), World War I began with the 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary. Due to the shifting and entangled alliances between European nations at that time, that single murder sparked a chain reaction that ignited the powder keg that Europe had become. As conflict spread throughout the continent, soon the major nations of the world joined in the fracas, aligning themselves with one of two distinct camps: the Central Powers (which included Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire) and the Allied Powers (Britain, Russia, Italy, France, Romania, Japan, Canada, and, finally, the U.S.).

The United States, in fact, was the last major nation to enter the conflict, with Americans loathe to join a war in Europe. It wasn't until after the Lusitania — a British ocean liner carrying nearly 2,000 civilians enroute from New York to Liverpool — was sunk by a German U-boat, resulting in nearly 1,200 casualties, that public opinion eventually shifted; America finally declared war on Germany in April 1917.

The war finally ended on November 11, 1918, when the Germans entered into an armistice agreement with the Allies, yet a lot of horrible things took place during those four years. To find out more, read on to discover why World War I was worse than you thought.

Trench warfare was brutal on soldiers

Arguably the most common image associated with World War I is that of soldiers in trenches. On the Western Front, soldiers on both sides of the conflict would dig long, deep ditches in the earth in order to protect themselves from enemy gunfire. They also served as the soldiers' homes for weeks at a time, built with planks of wood, sandbags, sticks, barbed wire, or, when none of these were available, simply mud.

The idea of fighting from trenches was hardly a new one; trenches had been utilized in warfare for centuries and had been common during the Civil War just a few decades earlier. By WWI, however, weaponry had advanced considerably. Trenches now protected men from machine guns and artillery attacks from the air. At the start of the war, both sides would launch attacks from their respective trenches, climbing out and running toward the enemy through what came to be known as "no man's land" — the space between the trenches — carrying rifles with bayonets affixed to the barrels. As the conflict wore on, entrenched Allied forces were just as likely to fall victim to German sneak attacks at night.

As one might expect, trench warfare was bloody and brutal, resulting in massive casualties on both sides. That was evident in the Battle of the Somme in 1916, when British forces experienced in excess of 57,000 casualties, with more than 19,000 deaths — on the first day of the battle.

Soldiers in the trenches also contended with a mysterious illness

The specter of being slaughtered by the enemy wasn't the only thing hanging over the heads of soldiers fighting in the trenches during World War I. In 1915, doctors working on the Western Front found themselves inundated with soldiers suffering from a mysterious malady with symptoms that included headaches, back aches, dizziness, and, strangely, stiffness in the shins. Within months, hundreds of these cases were identified, becoming so widespread that soldiers came up with a nickname for this strange new illness: "trench fever."

Trench fever was rarely fatal, but it grew common enough that it became a logistical nightmare for all armies engaged in trench warfare. Those afflicted were too ill for combat and were typically sent away from the front for up to three months — hardly an ideal scenario for military strategy.

As researchers dug in, they eventually determined the cause of the illness: the common louse — or, more specifically, louse excreta that was transmitted into the bloodstream via skin abrasions. With no pharmaceutical solution, the answer was to keep soldiers as free from lice (or "cooties," as soldiers began calling the tiny insects) as possible. A variety of methods were attempted, including allowing soldiers the opportunity to bathe regularly in addition to sterilizing their uniforms using steam or hot air. The Brits finally got a handle on things by developing a paste that combined creosote, iodoform, and naphthalene, which, when applied to uniforms' seams, proved quite effective at eliminating lice.

WWI introduced the large-scale use of chemical weapons

While there were many messed-up things that took place during World War I, one aspect that was particularly brutal was the large-scale use of chemical weapons. While it's easy to assume that the Germans were the first to introduce chemical warfare, it was actually France, which lobbed grenades loaded with bromine ethyl acetate, aka tear gas. The Germans did, however, raise the bar by developing a method to disperse clouds of chlorine gas — which, as harmful as it could be to foes, could be just as hazardous to those utilizing it if the wind direction happened to shift. As a weapon, the use of chlorine gas didn't last long.

Eventually, the most common chemical weapon used during WWI was so-called "mustard gas." The gas was nasty stuff, causing chemical burns, respiratory problems, and other issues for those exposed.

While mortality rates from this chemical were low — less than 2% — psychological damage was through the roof. In fact, numerous soldiers wound up experiencing what came to be known as "gas fright." "I was terrified of gas, to tell you the truth," Private John Hall of Britain's Machine Gun Corps said, as quoted in the scholarly paper "Terror Weapons: The British Experience of Gas and Its Treatment in the First World War." "I was more frightened with gas than I was with shell fire."

A worldwide pandemic accompanied the war, causing more fatalities than the war had

As World War I raged on, an unexpected phenomenon occurred at the tale end of the conflict: a global pandemic that was dubbed the "Spanish flu." The disease first emerged in the spring of 1918 with a seemingly harmless fever that lasted just a few days. By the fall of that year, however, the flu had mutated into a far deadlier version, hitting fast and often fatally; some were dead within hours of first experiencing symptoms, while others lingered for days until fluid filled their lungs and caused them to suffocate.

Despite its moniker, the flu didn't originate in Spain, but Kansas. Young men on their way to serve in WWI unknowingly carried the virus, and it spread quickly among servicemen living in close quarters. Once they made it to the trenches in Europe, the virus swept across the continent, taking victims on both sides as mortality rates grew to a staggering 10% in some areas. This was not an insignificant number; of 791,907 American soldiers admitted to army hospitals to receive treatment for influenza, 24,664 of them died.

The Spanish flu was ultimately responsible for the deaths of as many as 50 million people. By the time the pandemic ended, it had caused the deaths of 675,000 Americans, a greater number of U.S. casualties than World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War combined.

Servicemen who suffered PTSD largely went untreated

These days, mental health professionals are well aware that the extreme stress experienced by servicemen and -women who go to war can result in post-traumatic stress disorder. While PTSD is a widely acknowledged side effect of combat, that wasn't always the case — certainly not during World War I. The ailment, however, was widespread during the war, at the time termed "shell shock."

That term, in fact, was first coined by soldiers on the front lines, referring to comrades who had become so psychologically crushed by the horrors of war that they were simply unable to function. When British troops began experiencing this psychological malady on a widespread basis, military leaders were blindsided and decided to consult Dr. Charles S. Myers, an expert in what was then the relatively new discipline of psychology. Upon examining personnel exhibiting symptoms, he deduced that the cause was their repressed trauma; while he could treat patients on an individual basis, he recommended that the British army set up specialized units to treat the psychological casualties that resulted from massive battles.

However, Myers faced an uphill battle in converting the hearts and minds of those who believed that soldiers who claimed to suffer from shell shock were simply lazy or cowardly. Despite his efforts and recommendations, the vast majority of British soldiers suffering from PTSD went untreated, a phenomenon that became common among soldiers of all the nations involved in WWI.

Some horrific war crimes took place

Some truly awful things can take place in the midst of combat, and World War I was certainly no exception. In fact, some horrific war crimes took place during the war that remain among the most heinous in human history. Chief among these is arguably the Armenian genocide, when the Turkish government in charge of what was then known as the Ottoman Empire saw the war as an opportunity to achieve its nationalist goals. In 1915, the Turks began the deportation and outright killing of Armenians; when the genocide finally concluded in 1922, an estimated 600,000 to 1.5 million Armenian people had been slaughtered, and many more were displaced.

There were other incidents during World War I that were just as ugly. For example, when the Germans invaded Belgium, there were widespread reports of atrocities committed against civilians, including rape, arson, pillaging, and murder. A commission was established to determine whether these reports were accurate. It concluded they were, and that killing civilians and burning down entire villages had become widespread among German soldiers.

Ukrainian Canadians were locked up in internment camps

Among America's most shameful acts during World War II was the imprisonment of Japanese Americans in internment camps, but that wasn't the first time such a measure had been taken. During World War I, Canada wound up blazing that particular trail.

At the beginning of World War I in 1914, the Canadian government enacted the War Measures Act, which provided vast powers to suspend civil liberties during wartime. Using those powers, the government rounded up thousands of "enemy aliens," aka immigrants from nations with whom Canada was now at war. While many of those imprisoned were of German descent, the vast majority of prisoners came from Ukraine. They were rounded up and sent to remote, rural internment camps, their possessions and money confiscated.

There were 24 such camps scattered throughout the country; while imprisoned, these so-called "enemy aliens" were put to work on massive projects, paid so little that they were, for all intents and purposes, slave labor. In addition to those placed in camps, more than 80,000 immigrants from various Eastern European nations were forced to regularly report to authorities and carry identity cards denoting their status. It wasn't until 2005 that the Canadian government finally acknowledged its shameful actions, with Canada's House of Commons passing Bill C-331, also known as the Ukrainian Canadian Restitution Act.

Casualty numbers were so high historians still aren't sure how many died

There's no question that World War I was one of the largest wars in human history, and the amount of personnel involved certainly reflected that. With more than 30 nations involved, a staggering 60 million men were estimated to have fought in the so-called Great War.

Given that huge number, it's a given that the sheer volume of casualties was also higher than any previous conflict. To this day, however, historians are uncertain of the precise number of casualties, which are estimated at somewhere between 6 million and 13 million. The reason for that pretty significant discrepancy is that some casualty estimates lumped in those who died from such war-adjacent causes as the Spanish flu and the Armenian genocide, while others did not. However, a 2011 report ascertained that about 9.7 million military personnel lost their lives due to the war itself, while an additional 6.8 million civilians died during the same period. All told, approximately 16.5 million people died as a result of World War I.

Interestingly, the winners experienced far greater losses than the losers; Allied forces suffered casualties of 5.4 million personnel, while casualties among the nations of the Central Powers were just 4 million.

Troops taken from British colonies faced discrimination and inhumane conditions

As brutal as conditions were for the soldiers who fought in the trenches during World War I, they were considerably worse for those who were conscripted by Britain from its colonies. The British Indian Army, for example, was a massive force of 1.5 million troops. How they got there, however, is illustrative of colonialism at its worst, with a massive recruitment effort promising Indians substantial monetary rewards for joining. Once they'd signed on, however, they discovered that not only were they being paid a fraction of what their British counterparts were receiving, they were also subjected to blatant racism and issued inferior equipment. Their provisions, barracks, and medical care were also substandard.

A similar — yet arguably even more egregious — situation played out with the British West Indies Regiment. While Indian soldiers fought alongside British soldiers, the Black members of the West Indies regiment were initially relegated to supporting roles, used as labor to dig trenches, load equipment, and remove injured soldiers from the battlefield on stretchers. That work was inevitably life-threatening, done within the range of German artillery fire.

Like the Indian soldiers, the West Indies recruits were also the victims of racism, including the denial of a pay increase given to British soldiers. Frustrations with this intense discrimination eventually boiled over in Taranto, Italy, in December 1918, when recruits from the West Indies launched a four-day mutiny against their officers.

Propaganda and media censorship led to unintended violence on the home front

It's fair to say that America's skill at wartime propaganda really came of age during World War I. President Woodrow Wilson was elected largely on his promise to keep the U.S. out of the war, and there was initially little desire among Americans to enter the war. As as result, some serious finesse was required to persuade a reluctant nation to enter a conflict on a whole other continent.

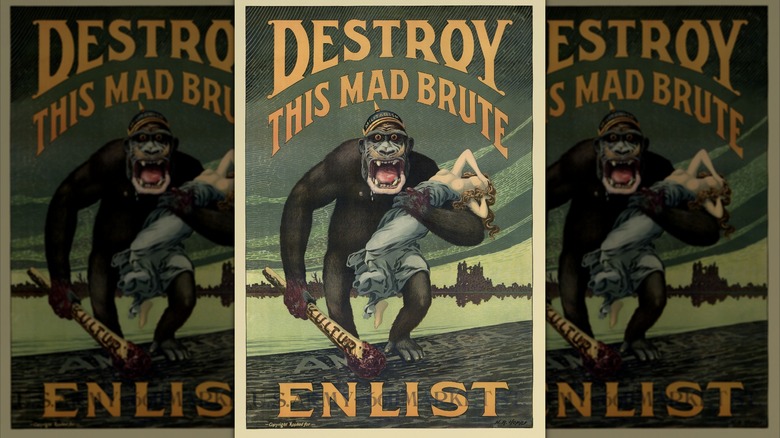

Enter George Creel, a PR professional whom Wilson placed in charge of both propaganda and censorship throughout the U.S. In order to whip up a pro-war frenzy among America's citizenry while convincing young men to enlist, Creel commissioned a series of posters and pamphlets that depicted German soldiers as vicious gorillas, clutching bare-breasted maidens in one hand while holding a bloodied club in the other.

Creel's strategy worked, convincing many that America needed to fight this horrific threat. However, his demonization of the Germans also yielded unintended consequences when mobs began forming to mete out vigilante "justice" by harassing and terrorizing innocent German immigrants. Meanwhile, churches that expressed pacifist views were rewarded by being set on fire, while anyone who appeared to be unpatriotic was at risk of being tarred and feathered by an angry mob. Whenever any of these vigilantes were captured and placed on trial — a rare occurrence, given the tenor of the time — juries were loathe to convict, fearing they themselves could become victims of similar outrage.

Hundreds of British soldiers were executed for deserting

For those who fought in World War I, death was omnipresent. It could arrive in a variety of guises, from poison gas or battlefield injuries to the Spanish flu, among others. For some soldiers who became psychologically incapable of coping with the daily horrors of the Western Front, one option that loomed was desertion; in fact, within the ranks of the British armed forces, approximately 10 of every 1,000 soldiers attempted to desert. Those who were caught, tried, and found guilty faced a grisly fate: execution by firing squad. All told, Britain executed 266 deserters during World War I.

A Scottish soldier, Private John McCauley, witnessed one such execution. Writing about what he witnessed (via Warfare History Network), McCauley recalled recognizing the deserter, with whom he'd trained, while some members of the firing squad were from the condemned man's hometown. "I still say that fear of facing a firing squad had little effect on the man whose nerves were shattered beyond repair and who eventually became panic stricken at the horrors surrounding him," McCauley observed.

America was far more lenient in dealing with its deserters. All told, 5,584 American servicemen were charged with desertion, and about half of those — 2,657 — were convicted. Of those found guilty, 24 were sentenced to death, yet none were executed, with President Woodrow Wilson commuting all their sentences to prison terms instead of a firing squad.