Things About D-Day That Don't Make Sense

D-Day was a big deal. The June 6, 1944, invasion of the European mainland, starting on the beaches of Normandy, France, across the English Channel from Britain, was a complicated and audacious move in the bloody chess game of World War II. An estimated 156,000 Allied troops were to make landfall on the coast, fight back against intense opposition, and move into the European mainland to face off with Nazi Germany and its Axis supporters. Deemed Operation Overlord, it sent troops to beaches codenamed Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword. When the first waves proved victorious — albeit after thousands of lives were lost on both sides — an estimated 850,000 troops and 148,000 vehicles used those beaches as their next step. It would prove to be a major turning point in the war. Less than a year later, Germany, battered by Allies on both its eastern and western fronts, surrendered on May 7, 1945.

So, between the historic import of the day and the many people involved — not to mention the immense complexity of a world war — it's no wonder that things remain confusing long after the fact. Do you really know why it was called D-Day? And how did Nazi commanders, who knew darn well that an invasion was coming at some point, manage to let Allied forces take the coast anyway? Even today, there are quite a few things about this historic point in WWII that take a lot of explaining, or simply don't make sense.

Why don't we know how many people died on D-Day?

D-Day was the largest amphibious invasion in history and the product of years of planning, including careful reconnaissance, international cooperation, and a complicated web of intentional miscommunications and double-agent activity meant to confuse the Germans. Despite heavy casualties, it proved to be a highly successful campaign that led to the defeat of Nazi Germany and the other Axis powers.

Yet there's one major issue that still isn't resolved: Just how many people died? Estimates vary wildly depending on whom you ask. Historical estimates put Allied deaths as low as 5,000, while others climbed as grimly high as 12,000. Most modern memorials estimate 4,414 Allied deaths, while at least as many Germans perished too.

No matter how much Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower and other leaders planned the attack, the simple truth of landing hundreds of thousands of soldiers on the beaches meant that it became a deadly mass of confusion. Some soldiers who died appear to have done so fighting with different companies, for instance. And while a valiant attempt was made to recover and record the remains of Allied soldiers in the aftermath, the brutal truth of what happened to the bodies from D-Day is that some remains likely washed out to sea and were never seen again. With the immediate need to take German positions and move farther inland, record-keeping was hardly at the top of commanders' lists (and wasn't prioritized by retreating Germans, either).

Why did the Germans fall so hard for a fake army?

Part of the lead-up to the D-Day invasion involved balloons. Actually, these were large inflatable mock tanks, which proved to be quite a success as part of the WWII ghost army you didn't learn about in school. This was Operation Fortitude, meant to fool watchful German forces into thinking that a long-expected Allied invasion was going to happen anywhere but Normandy. One sub-plan, deemed Fortitude North, drew attention to a supposed attack site in Norway. The other, Fortitude South, made it seem as if the Allies were mustering for an attack in Calais, northeast of Normandy.

Besides the inflatable tanks, radio operators put out false communications, while spies worked to create fake underground chatter revealing a Calais invasion. Airfields were prepared with aircraft that, if only Axis observers could take a closer look, would prove to be inoperable fakes. So, too, were landing craft made from heavy-duty fabric and wood. It was all set up as the First US Army Group (FUSAG). This group was fake, but its commander, General George S. Patton, very definitely was not. Patton gamely showed up for speeches and inspections of the fakery.

It may well be that Patton's role convinced Germany that FUSAG was real — why would the U.S. put one of its best generals there if a Calais invasion wasn't on the horizon? Even after it became clear that D-Day had targeted Normandy, Germany's 15th Army remained ready and waiting in Calais, as Nazi commanders were certain a second invasion was imminent.

German commanders made confusing decisions during the invasion

Besides the awkwardness of being fooled by inflatable tanks, Germany made other odd decisions that are hard to ignore despite Nazi propagandists' attempts to rewrite D-Day. These weren't just simple oops met with a shrug and "everyone makes mistakes," but decisions that seriously hampered troops' ability to counteract the D-Day invasion. For one, there was German commanders' insistence on following military protocols that were wildly out of date and focused on dogged counter-attacks. The idea was to strike when the enemy was depleted, but Allied commanders had already noted this strategy and effectively baited German forces to bring out the old, (once) reliable counter-attack ... only to continue with an intensified barrage of their own once the Germans had left their fortified positions.

Even worse, a significant number of German soldiers were by then poorly trained, as years of bloody war had made it difficult to fully prepare Axis forces in Europe. By contrast, many Allied soldiers had the relative luxury of more preparation before entering the theater of war (though it's worth noting that they met at least one highly-trained and deadly German regiment at Omaha Beach).

Meanwhile, Hitler had told his forces at Normandy to hold their ground as long as possible and stick relatively close to the beaches. This surprised the Allied soldiers somewhat, as they were expecting a more obvious retreat. But it did little to help the Germans, as clinging to the coast meant that they were well within range of heavy-duty guns and other munitions.

Why didn't anyone wake up Hitler?

On the morning of D-Day, while thousands fought in Normandy, Hitler slept. The night before, he may have thought an invasion, though all but inevitable, wasn't going to happen in the next few hours. There was a storm, after all, one so bad that some Nazi commanders had given themselves time off and left their posts in northern France. However, with the help of a break in the weather and distraction tactics like dummy paratroopers rigged with explosives, the Allied invasion went ahead anyway.

Even when news of D-Day reached Hitler's staff, they didn't wake him. They had been directed to let him sleep, and no one was brave enough to defy that order. When Hitler rose around noon, he dragged his feet, believing it was all another low-level distraction effort. It took hours and the urging of those on the ground in Normandy before he agreed to redirect troops and weapons to the attack.

If he had been awakened earlier by some brave aide, could Hitler have changed the course of that day? It's hard to tell, but he hadn't exactly distinguished himself as a military leader. He and other commanders had been fooled by the false Allied army created under Operation Fortitude, therefore mustering forces in the wrong place along the French coast. And when Field Marshal Erwin Rommel urged Hitler to boost defenses along the Normandy coast, Hitler told him that the formidable Panzer tank divisions ought to stay inland.

How have so many forgotten the war's best double agent?

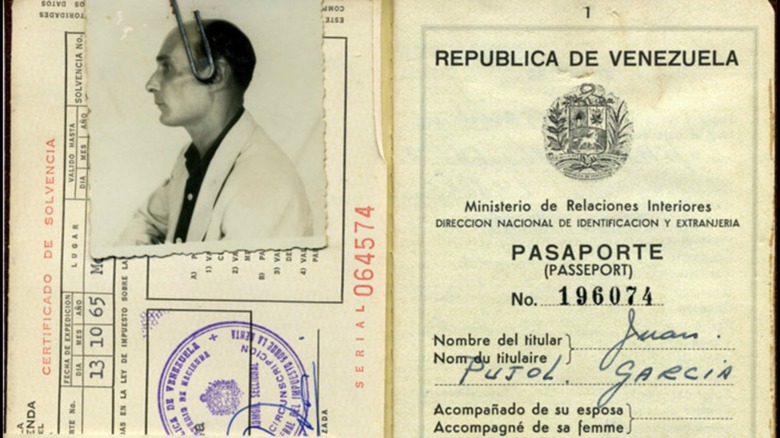

It's pretty difficult to overstate the importance of Juan Pujol Garcia's work during the war. The Spanish Pujol was no fan of rising dictator Francisco Franco and certainly wasn't on board with the power-grabbing of totalitarian Adolf Hitler. As World War II became reality in Europe, he attempted to join up with Britain as a double agent. Turned down due to his seeming inexperience, Pujol went ahead with his double agent activities freelance-style. He positioned himself as a Spanish government official with links to Britain and commenced sending false reports to Nazi contacts (sprinkling in legitimate facts to make the lies all the more believable). In 1942, Pujol approached Britain's MI5 again, revealing he was the secret agent who'd begun to catch their attention even while remaining unidentified. This time, they brought him on.

As for his connection to D-Day, the self-made spy Pujol helped to win the day. He once again set about lying to Nazi officials, telling them that these rumblings of a Normandy invasion were simply nonsense. Lulled into complacency by this and other Allied tactics, the Nazis weren't fully prepared when D-Day came to pass. Pujol remained an MI5 agent to tamp down a postwar Nazi revival, then faked his death (telling his handler to inform everyone he'd died of malaria) and moved to Venezuela. This was so believable that most people, including Pujol's own family, thought he really was dead until the 1980s.

The reason for calling it D-Day is confusing, at least to civilians

Though D-Day has been taught, studied, and discussed many times over since that day in June 1944, there's one key detail that tends to make things confusing. At least, that's the case for many civilians who aren't familiar with the sometimes complicated ins and outs of military terminology. Anyone who isn't in on the clipped jargon of military communiques may be left wondering why, exactly, we still call it D-Day.

The shortest answer makes it all the more confusing, at least at first. That's because the "D" in D-Day refers to ... well, "day." More specifically, it was common in the Army to use the term "D-Day" for the first day of a given operation. In a similar vein, "H-Hour" merely means the hour in which a given operation is set to begin. A simple system of pluses and minuses denotes days before or after a military action; for example, D+2 referred to June 8, two days after the June 6 launch of 1944's D-Day.

It may seem confusing if not downright frustrating, but there's actually a method to this rather vague standard. For one, being less specific allowed military commanders to be flexible with the dates — certainly useful if weather or compromised intel changed a timeline. Furthermore, if some info leaked, enemy forces wouldn't necessarily be able to figure out what was going on just by the intentionally vague terminology.

How have many forgotten that soil sampling was key to the invasion?

The heavy equipment that the Allies needed to land on Normandy beaches and move inland wouldn't have fared well on soft or boggy ground. For Allied commanders, the years-long process of planning D-Day therefore included sending out soil samplers. Yet for all their vital work — which sometimes required strict silence and a steel spine – those collectors are rarely mentioned. These men would approach French beaches as silently as possible using small craft (sometimes even miniature submarines), and then make the final trip to shore via engine-less canoes or swimming. Once there, they would dig up sand and soil samples and tuck them away in a jar or bag before returning quietly to the ocean. Often, these missions would take place under cover of darkness, though a variety of beaches were targeted with the assumption that German forces would notice and not be able to determine exactly where an invasion would make landfall.

These intrepid scientists took other key measurements, including water depth and how currents moved into and around the beach. Their information was so important that it convinced Eisenhower to focus on Normandy, where more compact sand gave forces the best chance. This also influenced some landing parties to include "Bobbin" tanks that laid down a steel mesh allowing other vehicles to follow behind without sinking. With such a key role, it's all the more odd that your history textbook almost certainly didn't give these samplers at least a mention.

How did Rommel drop the ball so badly?

Though some have concocted a picture of Nazi Field Marshal Erwin Rommel as a rather chivalrous figure, the truth is that he was a dedicated Nazi military officer. What's more, though he earned the grudging admiration of Winston Churchill and the nickname of the Desert Fox, Rommel's actual wartime record isn't quite that impressive. Among the things about World War II that don't make sense is how Rommel managed to secure such a lofty reputation when he was caught flat-footed on D-Day.

In 1943, Rommel was selected to command the German defense of Normandy. He directed personnel to plant landmines, build weapons platforms, thread terrain with barbed wire, and flood marshy areas to slow an Allied advance. Yet, he was also hampered by Hitler's unwillingness to divert powerful Panzer tank divisions to the region, as well as a sense of complacency brought about by bad intel and stormy June weather.

Rommel himself made some odd decisions, especially in light of his command role and clear evidence that the Allies were planning to invade somewhere in the region. Just two days before D-Day, he left the front to celebrate his wife's June 6 birthday. He reportedly gave her a pair of nice shoes, then rushed back to Normandy while moaning about his own poor choices. By the time he made it back, D-Day was effectively over, and the European side of the war had begun its turn in the Allies' favor.

How did a bagpiper manage to survive D-Day?

Bagpipes are not a subtle instrument. Even if your only exposure to them is through the distant lens of film or TV, you surely know they are loud and attention-getting. So why did one exceedingly brave bagpiper play his instrument on Sword Beach while British troops advanced? And, just as curiously, how did this man manage to survive?

The individual in question was Bill Millin, a Scottish private then serving in the British First Special Service Brigade. Before his group was about to land, Millin's commanding officer approached with an idea that was both highly traditional and exceedingly unusual. That officer, Brigadier Simon Fraser, 15th Lord Lovat, was both a hereditary Scottish aristocrat and someone whom Hitler allegedly regarded as a terrorist. Fraser, seeing Millin in his kilt, suggested that he break out the bagpipes. Millin noted that such music-making was technically banned, as it attracted enemy fire. Fraser's reported response was that, as the rule came from the English War Office and the two were Scottish, they could simply disregard the order.

So, Millin went ahead, walking back and forth on a Normandy beach while under fire and playing the bagpipes, all to raise morale. He also took on the traditional role of leading his group across a bridge, during which 12 soldiers were killed. Later, captured German soldiers allegedly said they didn't fire on him because they thought that Millin was in the midst of a mental health crisis.

Who exactly was Yang Kyoungjong?

Dig deep enough into the story of D-Day, and you may come across the sad tale of Yang Kyoungjong. As it's typically told, Yang was a young Korean man who was conscripted into Japan's army in the late 1930s. He was captured by Russia then conscripted into that nation's service in 1942. Captured in Ukraine, Yang was then forced into the German army and sent to Normandy, where he was yet again captured by the Allies on D-Day. Transported to a POW camp in the U.S., he eventually became a U.S. citizen and died in Illinois in 1992. His story has captivated many, from action filmmakers to noted historians.

Yang might be one of history's most unlucky people ... if only he was real. With a more careful second look, his story quickly becomes hard to confirm. A photo that allegedly shows a war-weary Yang in German uniform doesn't use his name. Instead, its official entry in the National Archives only identifies the figure as a "young Japanese man." Indeed, there's practically no documentation of a Korean man passed from army to army in the midst of this massive global war. There were Korean people who lived in Berlin under Nazi rule, but most appear to have returned to Korea by 1945. People of Asian descent were also at D-Day, including the unnamed Japanese man in a German uniform and, on the Allied side, multiple Chinese-American service members who stormed the beaches that day.