The Strange History Of California's Oldest Cold Case

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

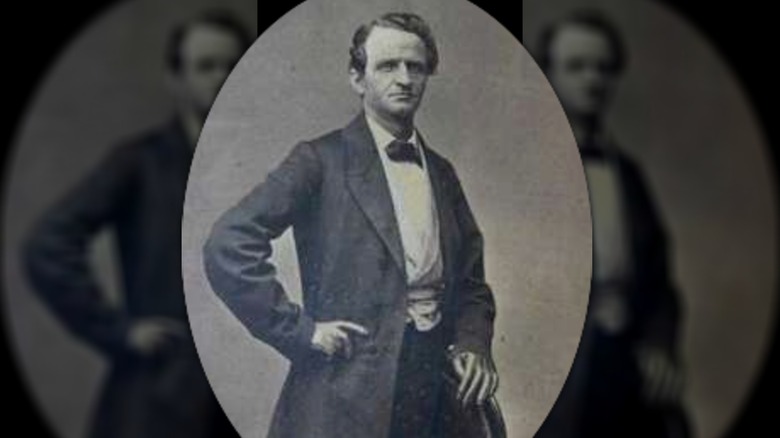

On the surface, it might not seem too strange: A well-known figure in business and government circles with a lot of money gets killed while sleeping outdoors on a cross-country trip with people he didn't know. That's exactly what happened to Herman Vollrath Ehrenberg when he died at the age of 49 in 1866 at Dos Palmas, near modern-day Palm Springs, California. But his death — California's oldest cold case — remains unsolved to this day.

Ehrenberg was quite a character with quite an interesting history. He was an immigrant from Prussia (part of current-day Germany) who came to the U.S. in 1834 at around 20 years old and joined the New Orleans Greys, a militia company that served in the Texas Revolution. There, he wrote firsthand accounts of the Battle of Coleto Creek, Massacre at Goliad, and the Siege and Battle of Bexar. Then, he participated in the California Gold Rush, helped rescue American sailors during the Mexican-American War, served as a judge in Arizona, and acted as a liaison to the Mojave tribe. He also worked as a surveyor and miner in the American West, to the point where he was called "one of the greatest surveyors and map makers ever to visit the Western United States," per the Mining and Minerals Education Foundation.

Ehrenberg's death came as a shock and generated some immediate assumptions. The Daily Alta posited that "some evil disposed one of these Indians" along his travels to kill him. Meanwhile, The New York Times called his death "a sad end ... to fall at last by the hand of the savage."

The night of Ehrenberg's murder

San Francisco's The Daily Alta reported on Herman Ehrenberg's murder on October 31, 1866, dating it to about two weeks earlier on October 14. Little explanation is given about Ehrenberg at the top of the article, indicating precisely how well-known he was. Later on, the outlet calls him "a man of fine scientific attainments" who, "as you know, had wide fame." He was "one of the very best of our people" whose "untimely death will create the deepest gloom in every section of the Territory." Journalistic hyperbole aside, it stands to reason that not just any death would make the front page of a paper.

As for the events of the crime itself, Ehrenberg died along the route from San Bernardino, California to La Paz, Arizona, a stretch of 225 miles using modern roads. He set out with two other people, Mr. Cushenburg and Mr. Noyes, who continued on to Prescott, Arizona after Ehrenberg had some trouble with his riding animal. Ehrenberg joined up with some "teamsters" en route (think: truckers who used animals instead of trucks) and pushed ahead of the group to make it to Dos Palmas near modern-day Palm Springs.

Ehrenberg got to the station at Dos Palmas and slept outside on a pallet because of the heat. The station's owner, W.H. Smith, heard a gunshot around midnight and went outside to find Ehrenberg near his bed, shot. He died shortly after, the teamsters reached the station the following morning, and he was buried. That's where the facts of the crime end.

[Featured image by Unknown Author via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

His death was originally blamed on Native Americans

Original conclusions regarding Herman Ehrenberg's murder pointed at one conclusion: belligerent Native Americans. To be fair, the Daily Alta approached this topic with genuine care and evenness. "It is just such a case of murder and robbery as is ever liable to occur anywhere, in the crowded city as well as the desert," it wrote. "The Indians along this road [from San Bernardino, California to La Paz, Arizona] have been perfectly peaceable and friendly, and the crime of one reprobate among them should not be visited upon them all." In other words: No vigilante justice, please. However, the article continues by fictionalizing events and describing a Native American "reprobate" trying to sneak into Dos Palmas station to steal something and Ehrenberg waking up from his pallet and getting shot.

The New York Times was less generous with things, coming late to the scene and writing about it on January 10 the following year, 1887. In a short, single-paragraph blurb describing Ehrenberg as a metallurgist, the micro-article begins by saying he was "murdered by the Indians in Arizona." Also, the paper says it happened only a month earlier and not three months earlier. That article, which we quoted earlier, ends by citing Ehrenberg's time as a tribal liaison. "It is a sad end, after spending so many years among all the tribes from Oregon to Mexico, to fall at last by the hands of the savage," it says.

Unraveling the murder mystery

It's possible to see how someone — tribespeople included — could have caught wind of Herman Ehrenberg traveling the trail from San Bernardino, California to La Paz, Arizona and planned to murder him en route. He was well-known throughout the region and not without money. Considering his involvement in business, political, and military affairs, someone could have held a grudge against him no matter how well sources at the time spoke about him. Still, the Daily Alta called Ehrenberg "a man of the greatest integrity, the purest morals, and the kindliest simplicity of character" who left "no enemy in this Territory."

That being said, if Ehrenberg was the target of the crime, there would have been far better opportunities to rob or even ransom him. But the Daily Alta article doesn't mention any of Ehrenberg's possessions being stolen — only that "some goods were missing" from the Dos Palmas station. The Press-Enterprise says that "some sources" claim Ehrenberg had $3,500 in gold on him (nearly $70,000 modernly), but gives no citations.

That leaves the crime of passion angle, which comes with its own issues. There would only have been a handful of people within striking distance of Dos Palmas station. This includes Ehrenberg's original traveling companions, the teamsters he traveled with for a bit, and the owner of the establishment. There are problems with all of these possibilities, like the teamsters lagging behind Ehrenberg leading up to the morning after his death. In the end, it's totally unknown whether he died at the hand of a random, roaming tribesperson or someone else.

An unsolved mystery to this day

There haven't exactly been any updates on California's oldest cold case since news originally broke. The death of Herman Ehrenberg remains one big shoulder shrug, and sources that describe it only recite the original events — nothing more. Nowadays, the truly intrepid can visit Ehrenberg's actual grave, set with a stone at the head scratched with his name (pictured right, above). It's located south of Joshua Tree National Park in Riverside County, California, about 2 hours by car from Riverside. Assuming that this grave is his original burial spot, visitors can catch a glimpse of the old travel route from San Bernardino, California to La Paz, Arizona. Interestingly, two individuals recently placed virtual flowers on Ehrenberg's grave on Find a Grave in May and June 2024.

Those wishing to learn more about Ehrenberg's colorful life — and not just his death — can pick up "Inside the Texas Revolution: The Enigmatic Memoir of Herman Ehrenberg," first published in 1843 in his native German. This account was published after he served in the Texas Revolution and went back to Germany in 1842 before heading back to the U.S. in 1844. If descriptions of the book are to be believed, it's the most thorough, firsthand account we have of the Texas Revolution, one published only a handful of years after the conflict ended. It would be a strange end, indeed, if Ehrenberg survived such events only to run afoul of a vagrant some 30 years later.

[Featured image by Ichbinjose via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]