Rules The Comanche Had To Follow Throughout History

The idea of the Native American in popular culture in many ways comes from the Comanche: powerful and nomadic warriors who gave the organized forces of colonial powers a run for their money. The Comanche were indeed fearsome fighters and some of the best mounted warriors ever seen, but their success as a group relied on skills beyond fighting. They were proficient traders who built networks that moved goods — and people — across the southern Plains. Their culture valued bravery and charisma, but also encompassed a personal spirituality built on relationships with nature and ancestral spirits. And though they were defeated as a military force by the United States in the 1870s, the Comanche Nation still exists, with its headquarters in Oklahoma.

Comanche society, like any other, was built on values, priorities, and rules that encouraged some behaviors, restricted others, and generally shaped the culture. Those rules governed relationships among individual Comanches and Comanche groups, interactions with outsiders, and encounters with the supernatural realm. Understanding the codes by which the Comanche lives allows outsiders to understand this significant Native nation better and to imagine, briefly, what the lives of the Comanche must have been like when they were masters of the Plains.

Master horsemanship

The Comanche were able to become masters of the southern Plains in large part because they were excellent on horseback. While the exact details how are not recorded, at some point in the late seventeenth century they obtained horses, which had been reintroduced into the Americas by colonizing powers. The Comanche adapted to this new means of transport with alacrity and moved southeast, leaving behind the culturally similar Shoshone whom they lived near in the Great Basin. This move allowed them better access to buffalo hunting, trade goods ... and the free-roaming mustang horses of the Southwest, descended from horses brought by Spanish settlers but since turned feral. Comanches and others who admired the tough little horses captured them for riding, and large herds could be maintained on prairie grasslands.

In addition to allowing the Comanche to maintain traditional nomadic ways of life and hunt migratory buffalo herds, horses served as markers and measures of wealth, as well as valuable trade commodities, both among the Comanche and in their relationships with outsiders. And perhaps most remembered, the Comanche prowess on horseback allowed them to become one of the most skilled and effective Native American fighting forces that other tribes or colonial governments would ever encounter, dominating their part of the Plains for generations.

Stay mobile

The Comanche's skill with horses was intimately connected to another aspect of their life, one that allowed them to remain among the most powerful, feared, and effective American Indigenous groups: mobility. The Comanche remained nomadic throughout their existence as a free tribe, never settling until forced onto reservations by the U.S. government. This was revealed as a military strength during their attacks against the farming Apaches, the preceding significant power on the southern Plains, which roughly took place between the 1720s and 1750s. The Apache had farms to protect while the Comanche didn't, so the Apache faced the disadvantage of having to remain where the Comanche could — and did — swoop in, wreck shop, and run off to fight another day if they felt the tide turning.

This smash (and smash and smash and smash) and grab approach to warfare also worked well against non-native powers. The Comanche outfought Spanish colonial armies sent up from Mexico City to "handle" them, forcing Spanish authorities to negotiate instead. Mexico, after its independence, was even less effective at checking Comanche power. Meanwhile, the mobile nature of Comanche society meant they were not only feared fighters but successful traders, transporting brokering goods (and, unfortunately, enslaved populations) among colonial powers, the emerging Mexico and United States, and other Native groups.

Fight to win

In nearly every scholarly and pop-culture treatment of the Comanche, they are described as excellent fighters. Their warfare against the Apache was designed to remove as many potential combatants from the board as possible. Effective guerrilla raids by night were designed to steal or kill livestock, start fires, and destroy food, all of which sapped Apache strength. Comanche warriors combined this approach with savage frontal assaults designed to kill as many Apache men as they could and capture women and children to feed into their burgeoning enslavement trade.

By 1750, with the remaining Apache having fled, the Comanche came into contact with French colonists and traders in the Louisiana territory, and from them obtained guns that were much better than the Spanish-made weapons they'd previously used. These guns — and the Comanche skill with them — allowed them to raid Spanish settlements nearly at will and resist government attempts to pacify them. After Mexico's independence in 1821, the new state was anxious to ally with the Comanche against a feared Spanish attempt at reconquest. Mexico was unable to keep up its obligations in its generous treaty with the Comanche, and so the Comanche returned to raid what is now northern Mexico, killing men, enslaving anyone else, and helping themselves to any movable wealth.

The Comanche's punishing attacks and the resentment they created among the remaining population are credited by some historians with the easy conquest of the Southwest in the Mexican-American War, with the invading U.S. troops finding scorched earth instead of resistance.

Understand trade

Trade both created the Comanches and made them powerful. They obtained their first horses through the Indigenous horse trade that emerged in the late 17th century, and one explanation offered for their initial move south is a desire to participate more in this commerce by getting closer to the source of the horses in New Mexico.

As the Comanche grew, they realized they could dominate trade in horses and bison products over a span of the southern Plains, if they but dealt with the obvious competitors, the Apache. With the Apache gone and French colonists eager to re-up on horses, buffalo hides, and meat, the Comanche found themselves well placed to receive manufactured European products ... including guns. Trade relationships with tribes further north allowed the Comanche to trade horses for British products from British Columbia.

The greatest strength of Comanche trade was their ability to provide horses — caught, bred or stolen — to whomever needed them. They were also willing to participate in the teeming trade of enslaved people. Initially selling captured Apaches, the Comanche then expanded into other populations as they raided New Spain and Mexico. They also received refugee Native groups expelled from the emerging United States, some of whom arrived with their own African-descended enslaved people in tow.

Stick to your family

While the Comanche were a coherent cultural unit with shared interests, they did not necessarily always act as a unit: the most important political divisions of Comanches were smaller. "Band" is a common but imprecise term in English for different levels of Comanche organization. Groups of extended families, related by blood, marriage or both, traveled together and functioned as a whole, and these smaller groups could align to form larger alliances. When circumstances dictated or interests were no longer shared, bands could merge, reorganize or split — another benefit of staying mobile.

Thirteen bands were recorded by observers of the Comanche, with five considered "major": the Penateka (Honey Eaters), who lived in Central Texas; the Nokoni (Those Who Turn Back), who shared their territory in northern Texas and New Mexico with two smaller bands, the Tanima (Liver-Eaters) and Tenawa (Those Who Stay Downstream); the Kotsoteka (Buffalo-Eaters), who lived along the Canadian River in Oklahoma; the Yamparikas (Yap-Eaters, which refers to a particular kind of edible root), who lived in western Oklahoma near the Arkansas River, and the Quahadis (Antelopes), who lived in the Llano Estacado plains of Texas and New Mexico. Additionally, many more bands must have existed over time without having been recorded by outsiders.

Show bravery

In a martial society like the Comanche, whose way of life relied in part on their fearsome reputation, individuals needed to show bravery to become valued and respected members of their group. One of the most notable ways for a Comanche warrior to do this was a ritualized aspect of combat called "counting coup," which was practiced by a number of other Plains tribes. To count coup, a warrior would approach an enemy closely enough to kill, but then instead merely touch or strike them. This practice showed superiority over the enemy — "could have killed you if I'd wanted to" — and also served as an honor to strive for and compete against one's peers to gain.

Counting coup, along with other markers of battle success, such as taking part in successful raids and battles, wasn't just good for bragging rights: the best and bravest fighting men were most likely to marry well and potentially rise to positions of leadership in the fluid Comanche hierarchy.

Marry wisely

With the extended family serving as the key subunit of Comanche society, it mattered who you married — even more than in European-descended cultures, you were really marrying the whole family. The ideal arrangement was polygynous (i.e., one man with multiple wives), but monogamy existed and instances of polyandry (one woman with multiple husbands) were also recorded. Sisters could be preferred as co-wives, but direct marriage between relatives was (wisely) forbidden. Marriage ideally involved the approval of a woman's male relatives, especially brothers, who would be given gifts of horses and possibly receive labor ("bride service") from the groom-to-be.

Weddings apparently rarely featured ceremonies: you just moved in together. Generally, a man would live in a teepee with his senior or favorite wife, with the others living nearby in their own teepees. Divorce was possible, although unsurprisingly (alas) more difficult for a woman to obtain than a man. A man could simply declare himself divorced, while a woman had to put herself under the protection of her brothers or, more dramatically, that of a new husband. Those male protectors could then either fight or pay off the initial husband to dissolve the marriage.

Seek spiritual power

Comanche religious practice was a personal, even private matter. They believed in a creator, Niatpo, who depending on the source is considered either to be one with the sun or distinct. In common with the spiritual beliefs of many of their peer societies in the Plains and Rocky Mountains, the Comanche believed in a world full of potential sources of spiritual power, called puha. This power could be gifted to an individual by animals, other aspects of nature, or by other human beings, alive or dead. Opossums, skunks, wolves, bears, bison, cedar, and peyote were among the species considered to have high amounts of intrinsic power.

Men and women both could become someone who possessed particularly strong or significant power, a role called puhakatl. Among other means, like transfer, inheritance, or training, this power could be sought in a vision quest, during which a young person would go to a higher altitude (as this is where spirits were believed to dwell) and fast, remain awake, and keep themselves isolated. If the spirits chose to grant puha to the seeker, they would then be able to practice spiritual medicine to help their fellow Comanche, either alone or as part of larger medicine societies.

Lead with confidence and charisma

Comanche society was democratic in its selection of leaders, with prominent men gathering to select leaders of a band or larger group by consensus. These leaders were chosen for particular skills that they had or respect that they commanded from their fellow, as well as personal charisma, and they could be replaced if they lost the confidence of the men who had chosen them.

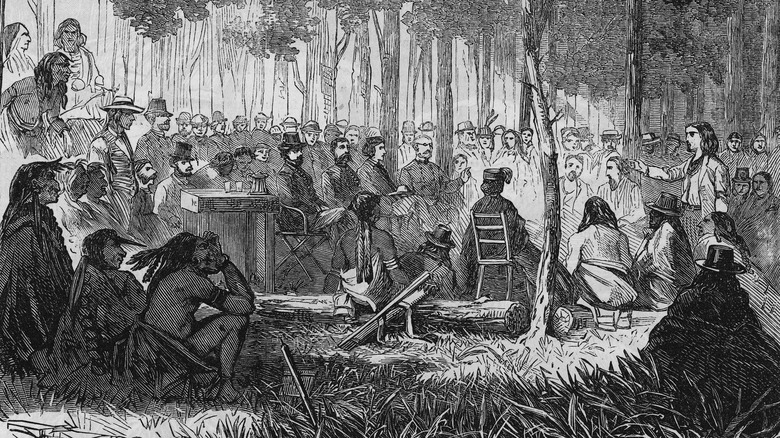

Comanche groups tended to elect both a war chief and a peace chief (who oversaw civil matters); the peace chief was generally higher ranking. In turn, these sub-chiefs could assemble in council to make decisions on matters affecting larger groups and/or many Comanche, though given the Comanche zeal for personal freedom, decisions were not binding on individual Comanche. (This individual freedom to act complicated matters with outside groups, especially European powers, who expected everyone to be governed.)

The Comanche continue to have a democratic government today. The modern Comanche Nation is run by an elected tribal council, which regulates tribal membership, administers federal programs, and fulfills various other responsibilities and priorities of the modern Comanche people.

Maintain the language

The Comanche language, Numu tekwapu, is part of the Uto-Aztecan language family, which includes languages from Ute, Comanche, and Shoshone — with origins in the Rocky Mountains — to the languages spoken by the Aztecs and related groups in central Mexico. During the Comanche heyday, it was widely spoken across the Plains, to the extent that it sometimes served as a regional lingua franca. Unfortunately, after the Comanche were forced onto reservations following their defeat as a fighting force, United States policies attempting to crush Native identity led many speakers to switch to English and children stopped learning the language. Nevertheless, several young Comanche men were among the Code Talkers of World War II, Indigenous men who used their languages, unknown to German or Japanese intelligence, to transmit sensitive military information.

For a time, it seemed Comanche might become extinct in the same way many other indigenous languages have died, but the Comanche have pushed back and are actively working to preserve their language. The Comanche Nation offers language learning materials and translation services for tribal members (be aware, though, that they will not translate your tattoo).

Keep the Nation going

After the Civil War ended, the United States government had more resources to use to mop up remaining Native American resistance to westward expansion, and the Comanche were among the groups fully in the government's crosshairs. A concentrated military campaign in 1874-75 forced the Comanche onto a reservation in Oklahoma (shared with the Kiowa and former foes the Apache), which was later broken up and allotted to individual residents, with the rest sold to white settlers, between 1901 and 1906. A Kiowa-Comanche-Apache Intertribal Business Committee was formed in 1936, which served as a consolidated tribal government until the Comanche broke off, wrote their own constitution, and formed their own tribal nation in the late 1960s.

Today, the Comanche Nation has nearly 10,000 enrolled tribal members and operates the tribal government from offices near Lawton, Oklahoma. The government provides services and cultural resources to enrolled members, ensuring that the Comanche retain both their sovereignty and their identity as a distinct Native nation. The current Comanche flag still calls them the lords of the plains.