The Messed Up Truth Of The Berlin Wall

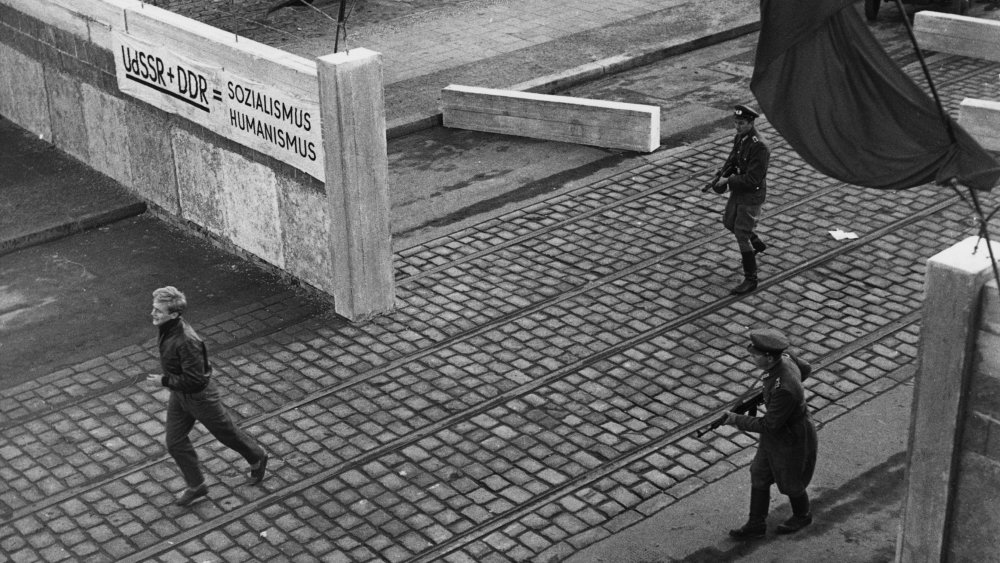

Before its dismantling on Nov. 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall was, to anyone living outside of divided Germany, a symbol of oppression and cruelty. For East Germans, it was more than a symbol; it was a constant reminder that they were not free to come and go as they chose. Rather, they were captives of their own government, the German Democratic Republic. And the guards who worked the wall's ramparts and checkpoints, the Grenztruppen, brazenly slaughtered the men, women, and children who attempted to cross it.

The GDR had many tools in place to subdue the East German people and ensure their loyalty to the state. The wall, known in Germany as "Die Mauer," was one of the most effective of these tools. Erected beginning on the early hours of Aug. 13, 1961, on what would become known as "Barbed Wire Sunday," the wall cut through Berlin like a scar, separating the communist East from the democratic West. It effectively put an end to East Germans defecting to the West, something that, according to the Independent, they had done by the millions up to that point.

Three decades have passed since Die Mauer came down, but its gruesome history stands as a stark reminder of the consequences of confining millions of people to lives of scarcity and bondage. It's also a lesson in what lengths humans will go to to break those bonds. Read on for an in-depth look at this brutal landmark.

The Berlin Wall was Russia's idea

The Berlin Wall was a stain on Germany's history, a monument to man's inhumanity to man. As such, no one has been terribly eager to take credit for it, especially following the reunification of Germany in 1990.

Some scholars have argued that the blame for the wall and its attendant atrocities should be laid right at the feet of the founder of the German Democratic Republic, Walter Ulbricht. Others have pointed the finger at Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet firebrand who oversaw the modernization of the USSR.

According to this article in Der Spiegel, Khrushchev was indeed the instigator. In a phone conversation dated Aug. 1, 1961, Khrushchev advocated for the need for "an iron ring around Berlin" to make sure that East Germany did not become a wasteland, a Cold War victim of brain drain. Khrushchev had scant trouble convincing Ulbricht of the need for a closed border with West Germany. Dismayed by the sight of millions of East Germans fleeing to the West for better lives and greater opportunity, Ulbricht readily agreed to Khruschev's demand that he lock up his own people.

To be fair to the Russians, as this article in the Independent suggests, the fall of the wall was likewise tied to a Soviet leader, albeit one who couldn't have been more different from Khrushchev. The mild-mannered reformer Mikhail Gorbachev and his perestroika movement helped inspire East Germans to rise up and demand freedom.

The Berlin Wall was really two walls

The Berlin Wall is somewhat of a misnomer. The 100-mile structure really consisted of two solid walls with a space in between, aptly called "the death strip." The strip was fortified with barbed wire and punctuated with guard towers. It also included runs for watch dogs and a carpet of steel spikes that patrolling soldiers, armed with rifles and gallows humor, referred to as "asparagus beds." According to the Berlin Wall Memorial Foundation, people in the West often referred to the spikes as "Stalin's lawn."

Nomenclature aside, the wall was designed to make surviving an escape attempt nearly impossible. Anyone hoping to leave the East would not only have to scale the wall (and avoid the spikes and guard dogs) but would face tank traps — railroad ties welded together and laced with barbed wire — and landmines. The area around the wall was lit up at night, and interior features were painted white to make it easier for guards to spot aspiring escapees. No one was safe, not even women and children, and while German authorities insisted for a long time that shooting those escapees was not part of the plan, a document unearthed in 2007 clearly illustrates that guards in the region of Magdeburg had explicit instructions from the East German Ministry for State Security, or Stasi, to shoot-to-kill anyone trying to flee.

War zone worship

Splicing Berlin into east and west turned out to be an incredibly complicated undertaking. This was particularly true on Bernauer Strasse where the wall butted so closely up to buildings that it was possible to walk through a doorway or peek your head out a window and, in so doing, go from communist East Berlin to democratic West. Even more surreal, a house of worship got caught in the crossfire.

According to World Magazine, Berlin's Church of Reconciliation became incorporated into the center-most part of the wall, often referred to as the death strip. When the wall went up in 1961, the church closed its doors. It stood for 24 years, unoccupied but largely unscathed. Then, in 1985, as East German Christians began agitating for the right to worship, communist leaders decided to blow the church up.

The decision blew up in their faces, though. Images of the blast, which showed the church's steeple tumbling into a nearby cemetery, were published around the world, and East German Christians redoubled their efforts, leading a protest movement that eventually ended with the fall of the wall.

The Berlin Wall was built by East German soldiers and citizens

While the Russians insisted on the building of the wall, it was actually East Germans who were conscripted to construct it. Work commenced late in the night of Aug. 12, 1961, when soldiers began stringing up miles of barbed wire between the East and West Berlin. Shortly thereafter, East German workers began replacing the wire with concrete.

According to History.com, many of the workers cried as they cut their own city in two. They didn't dare protest, though, because soldiers stood nearby, guns at the ready.

The wall ran for 27 miles between the two Berlins, but that was really only just one section of the whole 100-mile barrier. All told, the walling off of West Berlin took close to 6,000 miles of barbed wire. And the work was all done by East Germans. In effect, they built their own prison.

The Berlin Wall tore families apart

When construction began on the Berlin Wall, it progressed at breakneck pace, leaving many families, used to crossing freely between the east and west sections of the city, completely caught off guard. In this article on the wall's impact on Germans past and present, a man reminisced about getting a call from his aunt on the day before his birthday. It was Aug. 13, 1961, the first full day of the wall's construction. His aunt had called to inform him that she wouldn't be able to come for the birthday celebration. The wall lay between them, impassable.

Even more wrenching is the story of Ursula Bach, detailed in The Guardian. Bach had left East Berlin for the West when she was six months pregnant. She fled with her mother, a businesswoman who chafed at East Berlin's decision to bring businesses under government control. Bach, a Christian, left the East because she hoped to have her baby baptized. Her fiance, Fried, a devoted communist, stayed behind. Bach was sure he would follow her at some point, but then she heard an announcement on the radio that people would only be permitted to cross the barrier if they had special permission from authorities. She knew she was divided from Fried forever.

Bach was not alone. Thousands of Germans were divided from family and friends. Even after reunification, deep wounds remained, and many people died before they had the chance to see their loved ones again.

Countless people died trying to cross

Historians disagree over the exact numbers, but it's accepted fact that somewhere between 100 and 500 people died trying to cross the Berlin Wall from East into West Berlin. While the numbers are still in dispute — a Free University of Berlin study has narrowed the number to 262 killed, 24 of those border guards — what is perfectly clear is that guards subjected people trying to escape with callous brutality. Take, for instance, the story of a man who laying bleeding to death for almost an hour while guards watched. The incident took place a year and five days after construction on the wall began. Two men approached the wall and began to climb it. One man did manage to make it to freedom in the West. The other was shot in the back by East German guards.

West German guards witnessed the shooting and tried to toss the wounded man bandages, but he was stuck in the death strip. The man died in incredible agony, crying out for help. When he finally took his last breath, East German guards removed his body from view.

This kind of scene played out often in the more than 10,000 days of the wall's existence.

A network of spies behind the Berlin Wall

Life behind the Berlin Wall in East German was one of constant surveillance. The Stasi, the security apparatus of the German Democratic Republic, kept a watchful eye over East Germans, bugging phone conversations and trailing them on the street. Stasi officers were aided by the citizenry, and at the height of the surveillance state's power, one in three East Germans was an informant. As this Reuters piece points out, the Stasi relied heavily on loved ones turning on each other. Neighbors spied on neighbors; children informed on their parents. Personal privacy was nonexistent.

Even letter writing wasn't safe. According to the CBC, Stasi agents sometimes intercepted 90,000 letters a day, using the contents of the missives to build a case to throw the writers in jail. Prisoners were tortured. At the Stasi's most notorious secret prison, Hohenschönhausen, 1,000 people died in the span of six years. This was what people were trying to escape when they made desperate attempts to scale the wall or tunnel under it: an atmosphere of almost unbearable paranoia and oppression.

The dark life of a Berlin Wall guard

The East German border guards, or Grenztruppen, were feared, and for good reason. They had orders to shoot any and all people trying to cross the Berlin Wall and to shoot to kill. And, if a wounded escapee landed in the so-called death strip, the guards often looked on as the victim slowly bled out in front of them. They were known for the callousness they showed in the face of suffering. Their service, however, often came at great cost. According to the BBC, 24 guards (across both the Berlin Wall and the East-West German border) were killed while on duty — nine by people fleeing to the West, eight by their fellow guards, three by civilians, three by US soldiers, and one by a West German patrol.

44 guards died by suicide. One such guard was Conrad Schumann, whose daring escape is chronicled here by Al Jazeera. Schumann fled East Berlin on Aug. 15, 1961, just three days after construction began on the wall. His flight to freedom was captured on camera and he became a hero to his countrymen in the west. In the east, though, Schumann was a pariah, and not just to functionaries in the GDR. After reunification, he made the journey to Saxony to visit with the family he'd been separated from for close to 30 years. The welcome he received was not as warm as he'd hoped for, and, in the winter of 1998, his wife found him hanging from a tree.

The US gave the Berlin Wall its blessing

As a the world's most powerful liberal democracy and a leader in military might, the United States had a fine line to tread in its response to the construction of the Berlin Wall. On one hand, America's reputation as a beacon of freedom required that it condemn East Germany's decision to imprison its own people. On the other, President John F. Kennedy was eager to avoid a full-scale war with Russia, East Germany's main ally.

According to the Wilson Center, Kennedy was deeply concerned that the Cold War could explode into a very real war, pitting NATO forces against those of Russia and the Warsaw Pact. When he heard about the effort to erect a wall around West Berlin, he declared that a wall was "a hell of a lot better than a war."

But Kennedy was not resigned to ceding control of Berlin to Russia or the GDR. In October 1961, he sent General Lucius Clay to the city to oversee a deployment of U.S. troops to the border between east and west. The result was a standoff between Soviet soldiers and Americans at Friedrichstrasse Crossing Point, otherwise known as Checkpoint Charlie. The confrontation, as this examination of the U.S.'s military action shows, was fraught and tense. At one point, Soviet and American tanks were just 100 yards from each other. Both sides backed down, and American troops remained in West Berlin as a peacekeeping force.

Crossing the Berlin Wall was not pretty

From when the Berlin Wall was first erected in 1961 until it crumbled in 1989, roughly 5,000 people managed to escape East Germany to freedom in the West. That figure far outpaces the hundreds of people who died trying, but it also does not communicate just how difficult it was for escapees to emerge on the other side. People who tunneled under the wall risked tripping subterranean alarms. Many people drowned in the river Spree, trying to swim to freedom. A chemist in a hot air balloon plummeted to the earth and died an excruciating death.

Everyone who attempted escape faced grave danger. Speaking of graves, one escape route was via a tunnel that originated in an East German cemetery. Escapees would disappear under a headstone and literally claw their way to freedom. 23 people escaped that way before police were tipped off by an empty baby carriage resting by the grave.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, one of the most successful ways to escape was Tunnel 57, a 100-yard route dug by students in West Berlin eager to reunite with their girlfriends left behind in the east. The students began digging near a bakery, filling flour sacks with dirt and working in weeks-long shifts. It was grueling, dirty work. The tunnel ended in an outhouse. Tunnel 57 was so named because 57 people escaped to the West in just two nights.

War criminals escaped justice

One of the more grisly facts about life in and around the Berlin Wall was that East German border guards were not punished for acts of violence committed while on duty. The guards were, after all, acting on direct orders from their officers. Later, when Germany was reunited, the country's justice system wrestled with how to handle the very real horrors of the Grenztruppen. Should the guards themselves be held to account? Or should they focus on the men above the guards, who told them to shoot to kill?

The cases began with the guards, 90 of whom were convicted of manslaughter. Then Germany's courts moved onto putting generals and other higher-ups in jail. One of the most notorious heads of the Grenztruppen was Klaus Dieter Baumgarten, known to many as the Red General. He was convicted of five counts of manslaughter and another five of attempted manslaughter and sentenced to six and a half years in prison. He only served half his sentence before he was pardoned in 1990.

Even more frustrating to Germans hoping to see border guards pay for their inhumane actions were the trials of Erich Honeker, a leader in the Socialist Unity Party of Germany, and Stasi chief Erich Mielke. The men were charged with a host of crimes, including murder, but the cases were dismissed because both were in ill health.

The Berlin Wall is a video game

People who lost loved ones during the division of East and West Germany were horrified when, in 2010, a student named Jens Stoeber created a video game based on the Berlin Wall. According to this Reuters piece, Stoeber named the game "1378" in homage to the length of East-West German border in kilometers. The objectives of the game are clear: if play as an East German border guard, you're rewarded for killing refugees. Later, though, you must face a trial during which you may or may not be convicted for your crimes. If you choose instead to be a refugee, your aim is to escape. Should you get caught, you're either shot or arrested.

Stoeber claims that he intended the game to be educational. Critics, though, insist it's nothing more than an ego-driven, first-person shooter game that makes a mockery of the very real suffering people went through, living under a communist regime and trying — and often failing — to escape to freedom.