Presidents Who Were Unmarried While In Office

For nearly a decade, comedians and pundits have speculated about the nature of President Donald Trump's marriage to Melania Knavs. As well they might — Trump has been married three times, has a public history of infidelity, and he was found liable for sexual assault in a civil case. For all the jokes, rumors, and credible reports about a loveless, transactional marriage, the Trumps have stuck together for several decades now. But if they're bothered by any of the chatter around their union, they probably can't expect any relief over the next four years, given Melania's reported intent not to live in the White House (per CNN).

If that holds true after January 20, 2025, then Trump won't be the first president not to have a spouse with him in the White House, though he will be the first to have a living spouse who chooses to live separately. Four past presidents entered office as widowers, and one was a lifelong bachelor. Spread out over the first century of American government under the Constitution, none of these men were primarily known for being single. But for some, it was a point of question or controversy hovering over their administrations, and the circumstances behind their marital situations and how they dealt with it in office all differ. Read on to learn about the five unmarried presidents of the United States.

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson had a reputation as a solitary man, but at his home of Monticello, he loved to entertain. And in the early days of the plantation, he cherished time spent with his wife, Martha Wayles Skelton. They married at her home on New Year's Day in 1772 and passed their first cold, snowy night in Monticello with wine and music-fueled merrymaking. Very little information about Martha has survived to the present day. We have no images of her, but family history points to a happy, loving, and musically passionate marriage. The Jeffersons had six children together, though only two lived to adulthood.

Childbearing was hard on Martha, to the point where Jefferson rearranged his professional life to tend to her. Her last pregnancy in 1782 came on the heels of a narrow escape from the British during the Revolutionary War, and it left her in precarious health. In September of that year, she died after only 10 years of marriage. Jefferson was inconsolable after her death. Martha's dying wish was that her husband never remarry — her own father's numerous marriages had been hard on her — and Jefferson kept that promise.

Jefferson was almost 20 years a widower when he became president. His daughters sometimes acted as hostess for him, as did Dolley Madison. But it was in the early years of Jefferson's presidency when rumors of his long-term sexual relations with his slave Sally Hemings (which began after Martha's death) became a public scandal. It's been said that Hemings bore a strong physical resemblance to Martha.

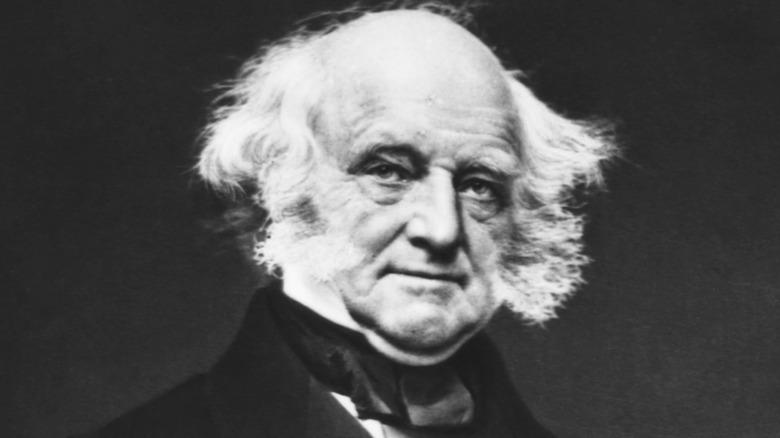

Martin Van Buren

In a presidential line-up, Martin Van Buren stands out for his massive whiskers and unkempt Friar Tuck hair. In the annals of history, he's known and respected for building up the Democratic Party — and much less respected for his time as president, saddled as it was with an economic depression. Van Buren's response to the crisis was limited, and he lacked the political clout within Congress to achieve what relief he did propose. His inability to meet the moment left him a one-term president, an unremarkable extension of the policies of Andrew Jackson, Van Buren's predecessor and patron.

Van Buren faced the depression and his political failings alone. His wife, Hannah Hoes, had been dead for many years before his election in 1836. Hannah and Van Buren were cousins — they were childhood sweethearts who both came from the same Dutch community. He was 24 and she was just shy of that when they married, and they reportedly had a happy union. But we know almost nothing about Hannah Van Buren. Her husband hardly mentioned her in his correspondence and didn't even include her in his autobiography. This shouldn't be taken as a sign of neglect, however — mores of the time considered it shameful to drag a lady's name into public material.

Van Buren had four sons by Hannah before her death of tuberculosis in 1819. They came with him to the White House. The oldest boy, Abraham, served his father as private secretary, while his wife Angelica became the de facto first lady.

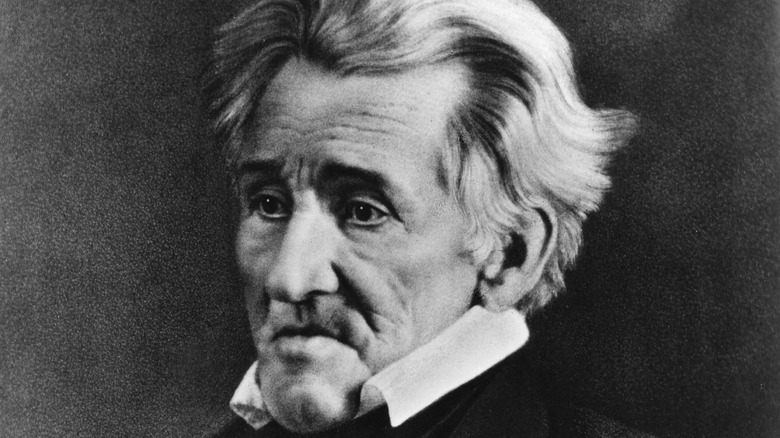

Andrew Jackson

There's plenty to not like about Andrew Jackson as a statesman and president: support for slavery, Indian removal policies, and imperious attitude towards government. And as a person, he was a hot-tempered and vengeful man with a body count. But he had a fiercely devoted following in his lifetime that gave him two terms as president, and there was at least one person with a deep personal affection for him. His marriage to Rachel Donelson, whom he first met in 1788, was a long and happy one.

They married in 1791, though their union was immediately marred by a technicality — Rachel was supposedly a divorcée but had not received a divorce from her previous husband, necessitating a remarriage to Jackson in 1794. Nevertheless, they were devoted to one another, sharing similar appetites and pleasures. Jackson, who lost all his close family at a young age, delighted in being a part of the Donelson family. He was also fiercely defensive of his wife's honor and was rankled when the opposing campaign seized on the legal snafu surrounding Rachel's divorce during the 1824 election.

Having her name dragged through the mud was unpleasant for Rachel, and she soon began to dread the prospect of being immersed in Washington, D.C. It was a future she had to face when Jackson won a resounding victory in 1828. But Rachel died in December of that year at 61, just weeks before her husband was sworn in. Jackson never remarried and grieved for the rest of his life. He and Rachel had no biological children, though they adopted one of her nephews.

James Buchanan

Ranking U.S. presidents is not an exact science, and it can be inflamed by the passions and politics of the moment. A recent list made after consulting with over 150 scholars, the Presidential Greatness Project Expert Survey, put Donald Trump dead last. That may change now that he has been elected for a second term. But a president just barely ahead of Trump in the survey is the perennial favorite for the greatest disaster to inflict the White House: James Buchanan. His legacy is letting the nation split apart over slavery and setting the stage for the Civil War (historians consistently rank him as one of the worst presidents).

Buchanan is also, to date, the only lifelong bachelor to serve as head of state. He was attentive and supportive to young relatives who lost their parents, and his niece Harriet Lane acted as lady of the White House for him. Together, they revived the social aspect of the presidency after years of neglect. But Buchanan's bachelorhood has inspired a long speculation that he may have been the first gay president. Per the Smithsonian, Buchanan maintained a long and close friendship with William Rufus King, a colleague from the president's Senate days, which has since been widely assumed to be sexual in nature.

Intimate — and platonic — relationships between men were common in the 19th century. Many politicians had such friendships. That Buchanan and King were close is apparent, but evidence for anything more remains scant. And while King doesn't appear to have courted anyone, Buchanan was engaged to Ann Coleman as a young man and was grief-stricken when she died.

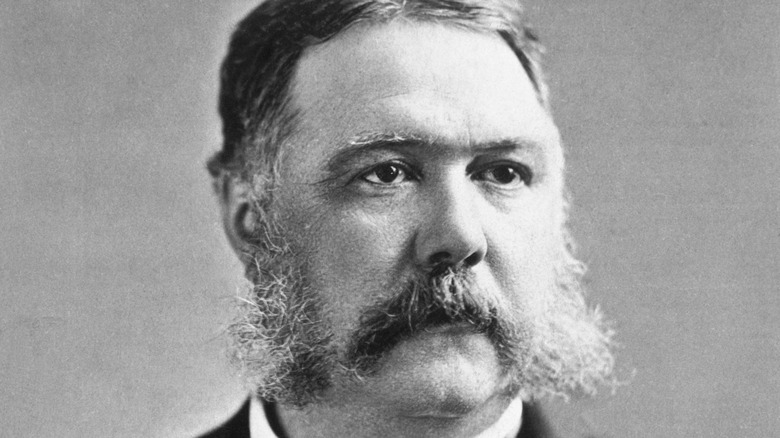

Chester A. Arthur

As of 2024, the last president to enter into office without a spouse is Chester A. Arthur. He's better known for his impressive mustache-sideburn combo and his political about-face upon being sworn in. Long considered a slick and partisan operator who benefited from the spoils system, Arthur was pushed onto President James Garfield to appease the pro-spoils Stalwart faction of the Republican Party. The public assumed he was unqualified and had little faith in his ability to take over when Garfield was assassinated. But Arthur, upset by the circumstances of his becoming president and the public perception of him, rose to the occasion. He threw his weight behind the Pendleton Civil Service Act, which helped establish a robust reform mechanism that continues to operate regardless of political headwinds.

Arthur's wife, Ellen Lewis Herndon, didn't live to see his transformation from spoilsman to reformer. She didn't even see him elected on the Garfield ticket — she died in January 1880 while the campaign was still underway. They had been married for over 20 years, having met through Ellen's cousin in 1856. The pair had three children together, though their firstborn died in childhood. Before Arthur's election, they maintained a happy and chic New York home and delighted in playing host and hostess for their friends. When he became president, he was loath to give anyone else duties that would have been Ellen's responsibility. While his sister helped with certain social functions in the White House, Arthur had no one equivalent to a first lady. He had a stained glass window installed in St. John's Church in her memory that he could see from the White House.