10 Famous Shipwrecks That Are Still Missing To This Day

Few things capture our imagination quite like a shipwreck. Whether it's a tragic tale of humans facing off against the sea, the allure of treasure buried beneath the waves, or simply the historical value of learning about a given ship, many of us are drawn to these stories. Even if you're a bit scared of the sea — and, after learning about some of the most notorious shipwrecks, who wouldn't have a healthy respect for the waves? — there's still something intriguing about the image of a lonely wreck waiting somewhere in the dark, cold waters. And while there are plenty of tales of shipwrecks found, perhaps more intriguing still are those that remain lost.

If you think that too many mysteries have been solved in the modern era, then you only have to contemplate some of the following stories to regain a sense of that old wonder. What happened to the Santa Maria, after all? Could a wreck weighed down with gold coins still be waiting somewhere off the coast of Cornwall? With enough effort, could we still find lost vessels from both world wars and bring closure to families these many decades later?

Santa Maria

For U.S. schoolchildren, the three ships that carried Christopher Columbus and his crew to the Americas are almost a litany: the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria. Yet, familiar as those names may be, we don't actually know much about what happened to them. The Niña and the Pinta eventually returned to Europe, but the Santa Maria — once the flagship of the three — was wrecked on a reef near Haiti on December 24, 1492. The timbers were reportedly salvaged to construct a nearby settlement, but upon Columbus' return to the area in 1493, it had burned down and any crew members left behind had either died or left.

Nothing of the Santa Maria-derived settlement has definitively been found, nor have searches along the reef uncovered the remains of a 15th-century ship that would fit the bill. Marine archaeologist Barry Clifford did claim to have uncovered the wreck, but a UNESCO team concluded in 2014 that what Clifford had found came from a much later shipwreck (via UNESCO).

Clifford and other archaeologists have set a seriously difficult task for themselves anyway, considering how both hurricanes and human activity have dramatically reshaped coasts in the Caribbean. That's not to mention the tall order of a largely wooden ship surviving centuries in warm waters crawling with shipworms, timber-chomping mollusks that could easily make short work of an already-wrecked Santa Maria. Still, there may be some trace of the ship left behind, meaning the search for a historic wreck continues.

Le Griffon

When talking about shipwrecks, it's easy to become focused on the vast waters of our planet's oceans. Yet, they aren't the only ones with yet-undiscovered shipwrecks. North America's Great Lakes — consisting of the interconnected Lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario — contain an estimated 21% of our planet's freshwater. At the system's deepest point in Lake Superior, there lies some 1,332 feet between the surface and bottom. No wonder, then, that the lakes still contain some of the most mysterious shipwrecks in history.

One of the most famous may be Le Griffon, which sank somewhere in northern Lake Michigan in 1679. Led by René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, the ship set off to find the Northwest Passage connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans – a key trading route that surely attracted the fur-trading La Salle. In September 1679, La Salle sent Le Griffon ahead, its hold full of furs to pay off his debts. But, as autumn came, it became clear that Le Griffon had vanished. Was it mutiny? A storm? To this day, no clear evidence for the ship's fate has been found, including its wreck.

In 2024, divers Kathie and Steve Libert told the Detroit Free Press that they believed they had found what remained of Le Griffon near a small island south of Michigan's Upper Peninsula. But others were vocally skeptical, saying that underwater footage shot by the Liberts shows a 19th-century shipwreck. To them, the search for Le Griffon remains ongoing.

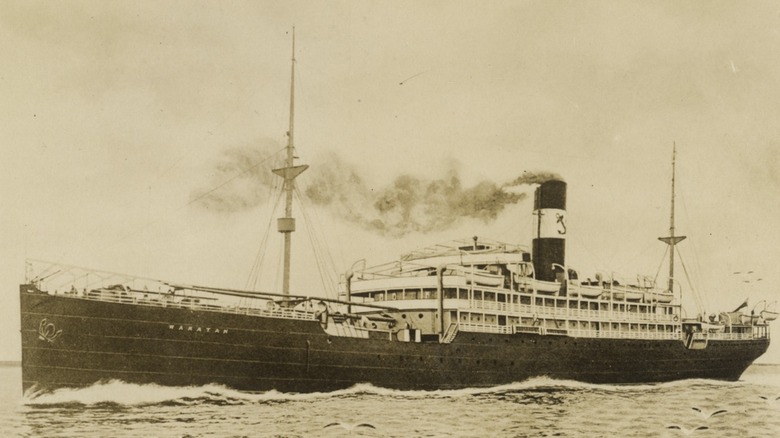

SS Waratah

While much has been made of the Titanic, which sank in the icy waters of the North Atlantic in April 1912, there are other major ocean liner disasters that deserve at least as much attention. And while the wreck of the Titanic was finally re-discovered in the 1980s, the 20th-century cruise liner known as the Waratah was not only dramatically lost, but remains unfound.

The SS Waratah was a large, luxurious British liner meant to travel between Europe and Australia. It left London on its first voyage in 1908, stopping off in Cape Town, South Africa, before making it to Adelaide, Australia, eventually making a safe return to London in early 1909. The second voyage was less uneventful. In June 1909, the Waratah — with 215 passengers and 119 crew — docked in Australia. It soon loaded up with cargo that included 880 tons of lead and 7,800 bars of metal bullion. It made it to Durban, South Africa, where engineer Claude G. Sawyer disembarked after noticing the ship rolled alarmingly in the waves.

Sawyer was grimly correct. The Waratah left Durban and, apart from a sighting by a passing ship, was never seen again. Several theories for one of the biggest unexplained mass disappearances focused on possible structural flaws in the ship, an overloaded cargo hold, bad weather, and even an explosion. But, despite intensive efforts to recover the wreck, nothing's come up. Even a champion of the effort, filmmaker Emlyn Brown, concluded in 2004 that the search for the Waratah had hit a wall (via The Guardian).

Flor de la Mar

There was a reason this ship was called the Flor de la Mar. Translated as the Flower of the Sea, the 16th-century vessel was the pride of Portugal. Well, at least it was in the beginning. It helped the kingdom score colonial possessions and was commanded by illustrious military figures. Yet, after Portugal took Malacca (now part of southwest Malaysia) and loaded treasures from the Malacca sultanate into the Flor de la Mar, things went wrong.

Embarking for home in November 1511, the ship was admittedly a bit rough around the edges, having been patched up many times and showing it. Departing Malacca, the ship skirted Sumatra and encountered a tempest so fierce that the Flor de la Mar broke apart and sank. The treasure sunk to the bottom of the ocean and some 400 sailors died, though some escaped to tell the tale.

Naturally, the wreck of the Flor de la Mar has attracted many treasure hunters in the intervening centuries. After all, the wreck reportedly contained a staggering 80 tons of gold, along with treasure chests full of jewels and coins that would make any pirate swoon with joy. Only, no one's been able to find it. Perhaps it was quietly looted by locals, the treasure sunk into ocean mud, or maybe the real reason we can't find it is because the Flor de la Mar has fully disintegrated. Or, just possibly, it's still out there, waiting to be found.

Merchant Royal

True to its name, the Merchant Royal was utterly loaded — both metaphorically and literally. The 17th-century galleon was a trading ship that regularly made its way between its home country of England and continental Europe. On its last trip, captain John Limbrey had directed the Merchant Royal into the port of Cadiz in Spain for a repair to its leaking hull. While there, Limbrey agreed to take on another ship's cargo when the other vessel was damaged by fire. How much there was is murky, but most sources agree that it was a serious amount of gold and silver destined to pay an estimated 30,000 Spanish soldiers waiting in Flanders, Belgium.

The soldiers never got their payday, at least not from the hold of the Merchant Royal. Somewhere between Cadiz and southwestern England, the ship's hull failed yet again and it began taking on water. It sank on September 23, 1641, about 30 miles from the headland of Land's End in Cornwall. It's said that 18 sailors died in the wreck, but Limbrey and some 40 others made it onto a nearby sister ship, the more seaworthy Dover Merchant.

The idea of all that treasure — estimated to be about $2 billion in today's money – lying tantalizingly close to Britain has proven compelling over the years. Yet, for all the speculation and stray bits of evidence — including an anchor recovered by fishermen in 2019 that might just have come from the wreck — no one's definitively found the Merchant Royal.

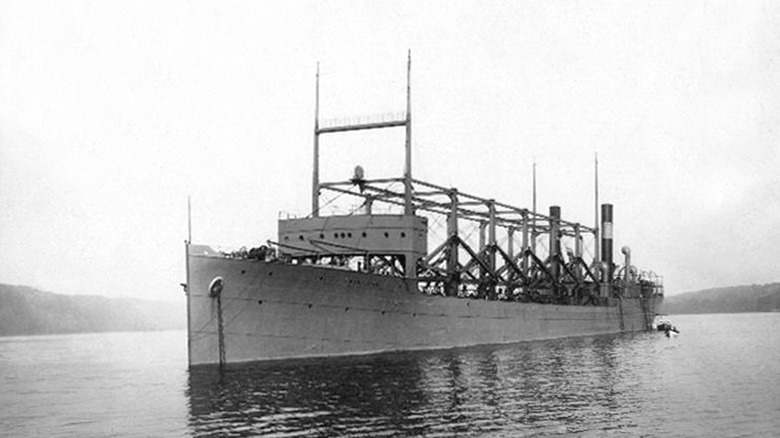

USS Cyclops

We all know that the ocean is large. But perhaps most of us land-based folk don't truly understand how stupendously vast the seas are until a major force such as the U.S. Navy loses one of its biggest ships. How big? In 1918, the USS Cyclops was one of the largest in the entire fleet, coming in at 540 feet long and 65 feet wide. Originally, it was a civilian collier meant to transport coal, but it was pressed into military service once the U.S. entered World War I in 1917.

On its last voyage, the Cyclops traveled to Rio de Janeiro to drop off nearly 10,000 tons of coal and return to Baltimore with 11,000 tons of manganese needed for the steel industry, a key component of the ongoing war effort. On the way back home, the Cyclops took an unexpected resupply stop in Barbados. Yet, after leaving port in Barbados, the ship never reappeared, becoming one more of the messed up things that happened during World War I. More than 300 sailors were aboard, yet no communications beyond a terse "Weather Fair, All Well" were received. Neither did anyone spot a foundering ship, pick up floating wreckage, or find any sign of the ultimate fate of the Cyclops.

Finding the wreck — presumably somewhere in the Atlantic between the U.S. and Barbados — would likely provide some answers. Yet, despite the efforts of explorers and some of the crewmembers' descendants, no trace of the lost Cyclops has yet been found.

Baychimo

It all began in 1914, when a cargo steamer left the shipbuilding yards of Gothenburg, Sweden, for its new home in Germany. First known as the Ångermanälven, it was turned over to Britain after Germany gave up many assets after World War I. By 1920, it had been sold to the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC). Now renamed the Baychimo, it began operating on the Canadian coasts. By 1924, it was moving up and down the icy western shores of Canada and the U.S. state of Alaska.

This was an especially difficult environment where ships were occasionally caught in the ice. The Baychimo even helped to recover the cargo of one such ship and, on subsequent voyages, narrowly escaped such a fate herself. Her luck came to a close in 1931, when a September storm battered the already-worn ship. By October, the Baychimo was locked in ice and the crew began snapping at one another. Some left via aircraft, while a small crew remained with the ship and its cargo, though the suddenly changing conditions caused them to camp nearby to avoid being aboard should a wreck happen.

After a November blizzard, they emerged to see that the Baychimo had disappeared during the gale. But instead of sinking, the now-loose Baychimo stayed afloat and occasionally reappeared before surprised locals as a mysterious ghost ship sailing the seas. However, no one was able to recover the ship. The last known sightings of the persistent wreck came in 1969, after which it is presumed to have finally sunk beneath the waves.

Surcouf

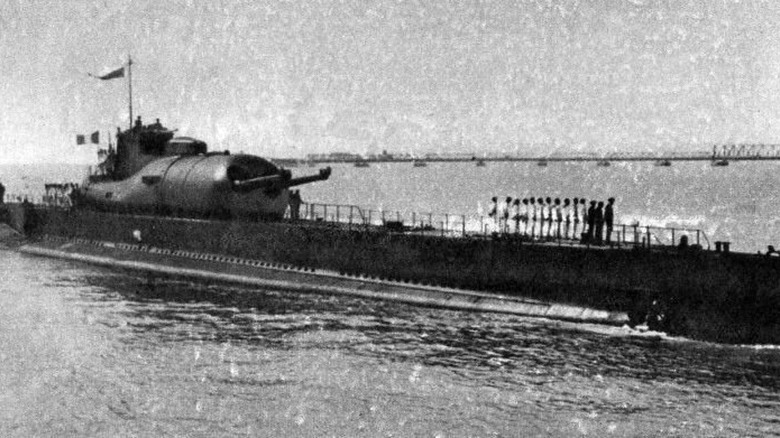

Among the submarines put into service during World War II, few were more astounding than the French Surcouf. Built in the late 1920s, it was 361 feet long, weighed in at 2,880 tons, and carried a crew of 150. This included some serious artillery, including two eight-inch guns and 14 torpedo tubes, as well as a seaplane — admittedly a small one for only two, but vessels meant to dive beneath the waves are hardly known for their complement of aircraft. The Surcouf spent much of its time during World War II escorting Allied craft in the Atlantic and Pacific.

However, in early 1942, something went wrong. Leaving Halifax for Tahiti, the Surcouf was meant to cross into the Pacific via the Panama Canal. Yet, by April 1942, The New York Times was reporting that it hadn't shown up at the appointed time and place and was considered to be lost. So, what happened? It's possible that the Surcouf, while on its way to the canal from a resupply point in Bermuda, was struck by a friendly vessel. The evening of February 18, the crew of American freighter Thompson Lykes was in the area and reported that it had struck something that had been partially submerged. Some have since suggested that this mysterious object was the Surcouf. Finding the wreck of this long-lost submarine would perhaps answer the question of its wartime end, and at least bring some closure to family members of the lost crew. Still, the Surcouf remains missing.

Andrea Gail

The disappearance of the Andrea Gail was certainly a tragedy, although only a local one at first, and it probably would have remained so if not for an aspiring freelance writer who lived in the ship's home port of Gloucester, Massachusetts. Sebastian Junger got to work, interviewing locals and piecing together the story of the lost fishing ship, which encountered a massive storm somewhere in the Grand Banks off the coast of Newfoundland and presumably sunk on October 29, 1991. A brief conversation between the Andrea Gail's captain, Billy Tyne, and fellow fishing boat captain (and "Deadliest Catch" cast member) Linda Greenlaw referenced the lousy weather, but was otherwise unremarkable. After that, the ship disappeared, with no radio communications indicating trouble. When it became clear that something had gone wrong, the U.S. Coast Guard began searching, but the efforts were called off after 10 days. The next month, the ship's emergency beacon washed ashore, but nothing else of the ship has been recovered.

Junger first published the story in Outside magazine in 1994. That story became a nonfiction book, "The Perfect Storm," which sold over 5 million copies and inspired the 2000 film of the same name starring George Clooney as Captain Tyne. Yet, the real-life wreck of the Andrea Gail has never been found. Finding it may or may not provide much new evidence about that fateful October night, but it would surely bring some closure to the families of the six men who were on board.

Inkerman and Cerisoles

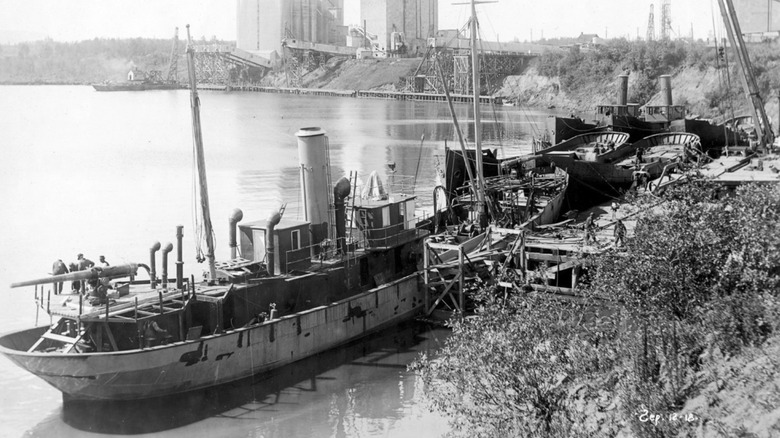

During World War I, there was unsurprisingly an increased demand for ships of war, including minesweepers meant to search out and neutralize enemy explosives. Their manufacturing partner for the French Navy was the Canadian Car & Foundry Company, which built 12 minesweepers for France during the war. Manufactured in Thunder Bay, Ontario, the ships were sent in small groups through Lake Superior, moving via canals and the other Great Lakes to the Atlantic. The final three included the Sebastopol, Inkerman, and Cerisoles, which left in November 1918.

The three encountered a fierce storm that hit while they were midway across Lake Superior. The ships lost sight of one another and, while the Sebastopol made it to safety, neither the Inkerman nor the Cerisoles was ever seen again. Yet the Sebastopol's crew assumed the other two had simply gotten ahead and that all would meet at the next port. Thus, it took days before anyone realized something was wrong. Despite a large search, the missing ships were never found.

There are tales, including one eerie legend of human remains found on a Lake Superior shore in 1919, sporting a French Navy uniform. Certainly, something of the Inkerman and Cerisoles remains in the depths of Lake Superior, though whether or not someone will find the wreckage and answer lingering questions about the ships remains to be seen. High-tech expeditions using side-scan sonar haven't yet found the minesweepers, though they have come across a long-lost 1879 vessel in the process.