Things About World War I That Don't Make Sense

When it comes to complicated wars, surely World War I is near the head of the pack. While there had already been numerous international wars beforehand, the commencement of the First World War in 1914 was the result of many years of simmering tensions, imperial ambitions, personal foibles, and more. It created what was widely considered the first global conflict, one which certainly involved a dizzying number of nations working together or pitting themselves against one another.

Beyond teasing out the tangled mess that caused such a massive war, there are many other confusing circumstances and incidents that still don't make sense about the Great War. Some nations routinely blocked able-bodied soldiers from joining the fight, while others just couldn't figure out how to move beyond grueling trench warfare until the arrival of tanks made it all a moot point. Yet more lost entire ships and perhaps even entire divisions ... that is, if wild rumors and colorful legends haven't obscured things even further. And, perhaps just as confounding, some who contributed vast amounts of time and effort to the cause were literally painted out of history. It doesn't help that, in the intervening decades, we've also come up with some common myths about the First World War that make things all the more obscure.

Why did the war start in the first place?

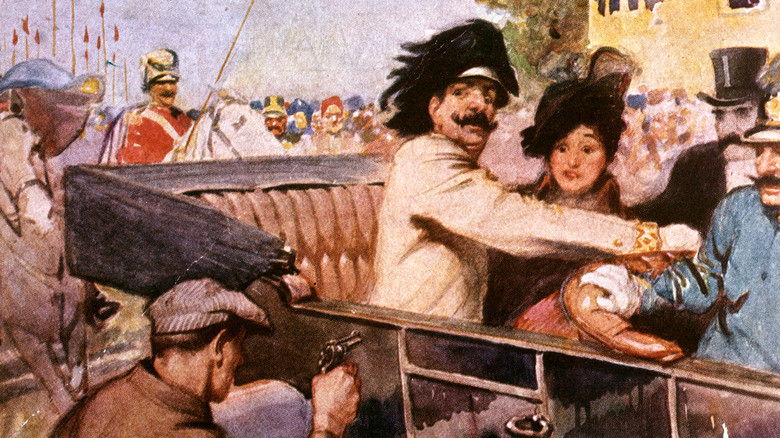

The explanation often given for the breakout of World War I is the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand on June 28, 1914. But, tragic as it may have been, a single assassination event (Ferdinand's wife, Sophie, was also killed that day) doesn't quite stand as the sole reason for WWI. Over a century later, it still doesn't always make sense.

We can at least narrow it down to a few key events and circumstances. First, there was the complicated roil of alliances and conflicts creating tension, including the 1894 Franco-Russian Alliance formed in response to growing coziness between Austria-Hungary, Italy, and Germany. Meanwhile, Russia became embroiled in its own war with Japan in 1904 and 1905; when it lost that war, Russia began to grow more interested in its Western European neighbors. Its seemingly embarrassed military commanders simultaneously decided that they would be far more aggressive if another conflict arose. Ultimately, Russia would back Eastern European nations that made up the Balkan League, which faced off against the Ottoman Empire in the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913.

Meanwhile, other nations caused further trouble, from the land grabbing of Austria-Hungary in Serbia to the increasing militarization of Germany to Italy invading Libya. By the time the heir to Austria-Hungary, Archduke Ferdinand, was touring Sarajevo in 1914 to inspect the empire's occupying troops, he was atop a powder keg waiting to explode. His assassination by rebel Gavrilo Princip simply provided the spark.

Why did the U.S. insist on staying neutral for so long?

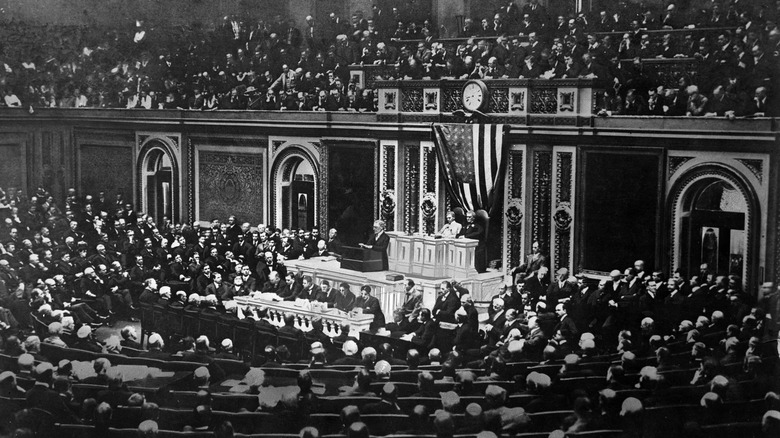

Though World War I began in 1914, it took nearly three years for the United States to enter the conflict. Given how the war had produced dramatic, international shockwaves, why didn't the U.S. join in the fight earlier?

Domestically, President Woodrow Wilson and many other Americans thought entering the war was a bad idea that would be both expensive and bloody. But the U.S. wasn't exactly neutral, as both private citizens and the government sent considerable money to the Allies. But it's worth remembering that a significant portion of Americans — just under 10% at the time — were of German descent and surely felt themselves to be in a complicated position.

Moreover, by the beginning of World War I, the U.S. was a world power — but just barely. Most historians now consider that the nation became a major player on the world stage after the end of the 1898 Spanish-American war, when the Treaty of Paris left the U.S. a newly-minted colonial power in possession of former Spanish territories like Puerto Rico and Guam. Yet at the outbreak of war in July 1914, the U.S. had only been in such a position for a little over 15 years. It took increasing German aggression, including the 1915 sinking of the RMS Lusitania (killing 1,195 people, of whom 128 were Americans) and an escalation of German U-boat warfare in 1917, for the U.S. to finally declare war against Germany.

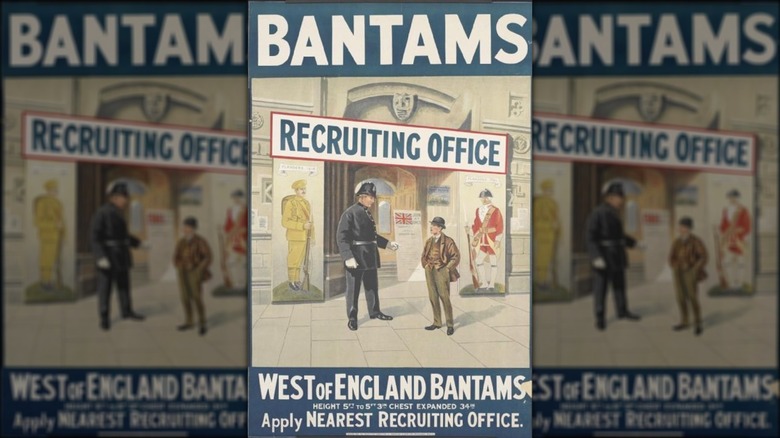

Why did the British Army care so much about soldiers' height?

Though World War I effectively began in continental Europe, Britain was involved from almost the very beginning. Though the increasing tensions across the channel were at first treated like sad but far-away news, it was only a matter of weeks from Archduke Ferdinand's July 1914 death until Britain declared war on Germany on August 4. Troops were soon mobilized for action ... well, some of them. There was what may now seem to be a nonsensical height requirement for British troops that blocked recruits under 5 feet, 3 inches.

Thousands were reportedly turned away from recruiting offices, with some local government officials taking up their cause. Minister of Parliament Alfred Bigland eventually secured permission to establish a regiment of short men, finally allowing them to fight. Ultimately, some 29 battalions — popularly known as bantam battalions — made space for men between 5 feet and 5 feet, 3 inches tall to join the fight, albeit with officers of "standard" height. Eventually, the British Army lowered height requirements to encourage more recruits, dropping to as low as 5 foot, 2 inches for general service.

Why not just lower the height requirement even further and skip the hullabaloo of upset applicants and bantam battalions in the first place? For some officials, it may have seemed to be too much work and, with the initial expectation by some that the war would fizzle out soon enough, it just wasn't a priority.

Why did Japan come to the aid of Britain?

It may be surprising to hear that in the early 20th century, Japan was once an ally of Britain. But, World War I set the stage for Japan's budding global ambitions and planted the seeds for its role in World War II. By the early 20th century, Japan was clearly unsettled by Russian expansion and its enthusiasm for the Russo-Japanese War in 1904-1905. Japan had entered into a 1902 treaty with Britain to fight back against future Russian aggression, including potential help from the powerful Royal Navy, and while Britain didn't officially join the Russo-Japanese War, it did lend serious help to build up Japan's navy. That Japanese navy was subsequently deployed when Britain declared war against Germany in August 1914.

By the end of the month, Japan had also declared war against Germany and Austria-Hungary. Though much of the fighting took place far from Japan, Germany possessed Asian and Pacific territories that were considered too close to home. Japan set about taking control of these, including the Chinese port of Tsingtao (now Qingdao), the Marianas, and the Marshall Islands.

This was viewed by Japanese officials as an opportunity to become a major power and get in on some expansionism of their own. Besides naval actions that fended off German forces, Japan also built ships for and sold munitions to Allied forces. In 1917, the U.S. even secretly allowed Japan to patrol the waters around American-held Hawaii — which became darkly ironic after the 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Why did it take so long to figure out the key weakness of trench warfare?

Trench warfare had been used in previous wars but gained awful distinction in WWI. Deployed most commonly on the Western Front in northern France and Belgium, this form of warfare saw troops emerge from trenches and attempt to advance across the barren "no man's land" between sides. But this produced rampant death and little progress. And when troops stayed put for long stretches, the reality of living in WWI trenches included filthy, dangerous conditions that brought disease and serious mental trauma.

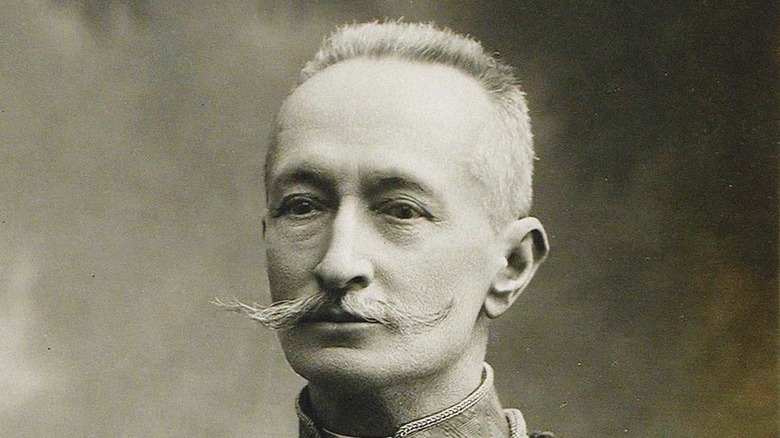

By 1916, Russian general Alexei Brusilov realized that the strategy of sending soldiers across no man's land to break through a single point wasn't working. This strategy made it too easy for opposing forces to focus on that point, producing mass casualties and little else. Brusilov's plan was to spread out the attack, making it more difficult for Austrian troops to see just where the Allied forces hoped to break through — and it worked, at least at first.

There were significant drawbacks to this, as Brusilov's strategy required absolutely massive numbers of soldiers. This initially wasn't too much of a problem for Russia's populous army, but presented a serious issue when it came to supplying them. Ultimately, the plan faded as feeding and arming personnel proved unworkable. Trench warfare, at least as it was fought in WWI, only reached its end when tanks became more common at the end of the conflict.

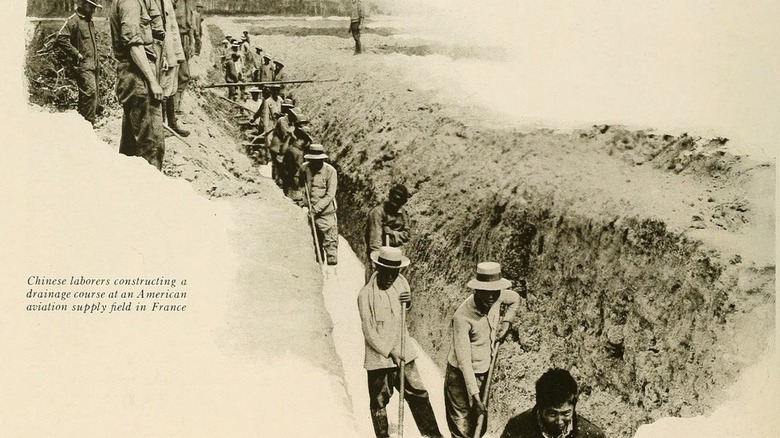

How did everyone forget the Chinese Labour Corps?

While so many war stories concentrate on the heroics of soldiers, such stories wouldn't be possible if it weren't for the unglamorous work of others. Some non-combatant workers of WWI have gained recognition, like lesser-known WWI heroines such as the women switchboard operators of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, known as the "Hello Girls." Yet there are still more laborers whose important work is rarely discussed.

The Chinese Labour Corps came into being in 1916, when the increasing toll of war created labor shortages in Europe. An estimated 81,000 men crossed the Pacific Ocean, Canada, and then the Atlantic, with many dying along the way. When the survivors finally made it to France and Belgium, they dug trenches, repaired equipment, built roads, and unloaded cargo — all in 10-hour days that lasted all week. After the war, many stayed to exhume battlefield graves and transport the remains to cemeteries, while others cleared live bombs.

Despite the considerable labor of these thousands of men, their contributions were barely acknowledged. They were even literally painted out of history, as China was excised from a post-war painting meant to show all the Allied nations (ostensibly to make room for latecomer Americans joining the fight). At the 1919 Paris Peace Conference that produced the Treaty of Versailles, China grew upset when the other Allies reneged on their promise to return control of Japanese-seized territory to China. Stung, the nation's representatives refused to sign the treaty.

What did soldiers see at the Battle of Mons?

The legend of the Angels of Mons typically goes as such: in August 1914, British soldiers faced off against Germans in southern Belgium, near the small town of Mons. This was the first major battle of the war, and things were looking stark for the British. Thousands lost their lives, but the British soldiers were not completely annihilated. According to some contemporary accounts, that was thanks to the miraculous intervention of angelic figures. The situation was muddied by the publication of a short story, Arthur Machen's "The Bowmen," in September 1914. In it, ghostly medieval archers defend British troops after one soldier appeals to England's patron Saint George for help.

While Machen's story was presented as fiction, subsequent accounts were less clearly so. Some readers genuinely believed that angelic figures helped defend real British soldiers at Mons. Or was it a strange cloud that blocked the Germans? Or a man on a huge white horse that only some witnessed?

The sources for these various tales were hard to track down and ever-changing. These included an unnamed officer, a mysterious nurse, or vague second-hand accounts. No definitive eyewitness to a mystical defense at Mons was ever found. Nonsensical as it may sound, however, there's a clear psychological drive behind the tale. Mired in an agonizing conflict that threatened to go on for years, an inspiring legend of angels protecting beloved soldiers in the heat of battle surely appealed to those back home.

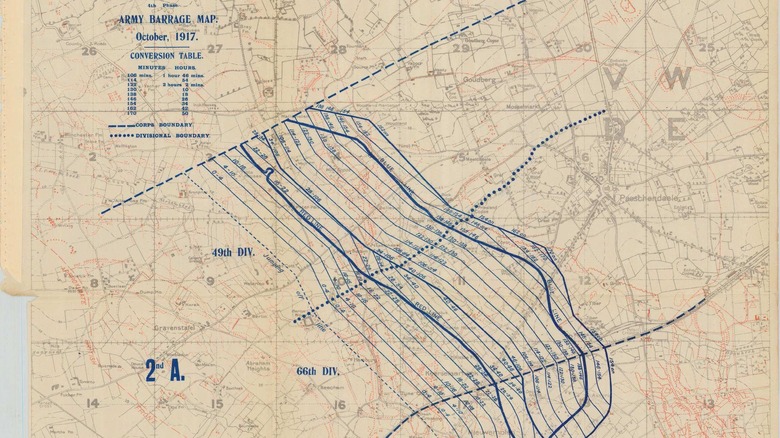

Why is there so much confusion over Celtic Wood?

Australia had a significant presence in World War I, with over 330,000 soldiers serving in the war and an estimated 60,000 who died during it. Of those casualties, the most mysterious may involve the 10th Battalion of the 1st Australian Division at a 1917 battle in Belgium. Also known as the Raid on Celtic Wood, this October 9 attack saw 85 soldiers attacking a series of German positions in a wooded area, in concert with the nearby Battle of Poelcappelle. But it proved to be a deadly misstep. According to historian C.E.W. Bean, writing in "The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918," only 14 returned and the others were never accounted for. Some even said it was as if they had disappeared amongst the trees.

Bean was a war correspondent who witnessed at least some of the events that day, but didn't offer much else in his account. Neither did the Germans, who recorded nothing of that day at Celtic Wood. Some concluded that the missing 59 men were massacred and hastily buried, though no human remains nearby have been uncovered. Perhaps they were transported elsewhere, but no proof of that has been revealed, either.

However, some accounts, including original sources compiled by Virtual War Memorial Australia, suggest all men were accounted for. Bean's short mention of Celtic Wood may have been misinterpreted by less-cautious writers, but then it's unclear how it turned into the mystery some claim it to be.

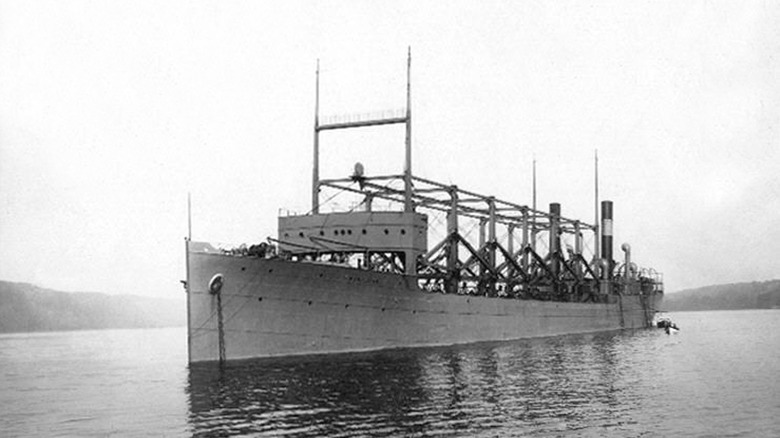

How did the U.S. Navy lose track of one of its biggest ships?

How does one manage to lose track of a 550-foot-long ship with a crew of 306 people? The U.S. Navy has been wondering just that since the USS Cyclops disappeared in 1918.

With the entry of the U.S. into World War II in 1917, the Cyclops was put into service as a collier ship, transporting troops and coal. In March 1918, it went to Brazil to load up on 11,000 tons of manganese for steel manufacturing. The last known communication came from Commander G.W. Worley, who noted that a shipboard engine had cracked and reduced the vessel's speed as it came into port in Barbados. A response recommended the Cyclops return home for repairs and it left Barbados on March 4, but the ship and all its crew never made it back to the U.S. No evidence of its fate came to light, and it's since become part of the strange history of the Bermuda Triangle.

Enemy attack was first considered to be the ship's most likely fate, as German vessels could have easily determined that the Cyclops was a perfect target. Yet, later evidence indicates that Germans weren't in the area. Perhaps, overloaded as the ship was with ore, she foundered, experienced a disastrous engine failure, or even failed when a mutinous crew took over and was unable to manage the heavily loaded ship. To this day, more than a century after its last communication, the abrupt disappearance of the Cyclops remains confounding.

Why did the Treaty of Versailles flounder?

World War I officially ended on November 11, 1918 when Germany — hit hard by dwindling supplies, casualties, and the advance of Allied forces– signed an armistice agreement. The terms of this surrender were agreed upon in the Treaty of Versailles, signed at France's Palace of Versailles on June 28, 1919.

Yet, the treaty came on tremendously shaky ground. Germany only reluctantly signed onto the document, while the U.S. never even bothered to ratify it (the Senate was opposed to President Woodrow Wilson's League of Nations outlined in the document). In the following years, Germany went ahead with rearmament despite strictures in the treaty, while France and Britain only weakly enforced its terms. Ultimately, it did little to stop worsening economic conditions in Germany, which was initially expected to pay billions in reparations, and arguably led to the emergence of Nazi Germany and World War II.

Why was the Treaty of Versailles such a flub? Perhaps it's because so much of the postwar world blamed Germany and its people for the destruction of the war, and therefore levied harsh economic and political sanctions against it. That hardly helped with geopolitical instability in the region, which only grew after the war, partially because the treaty drew tricky new borders in some regions. The treaty itself was a long, confusing mess that seemed to satisfy absolutely no one, least of all the defeated nations that had practically no say in the details.