Things About The Vietnam War That Don't Make Sense

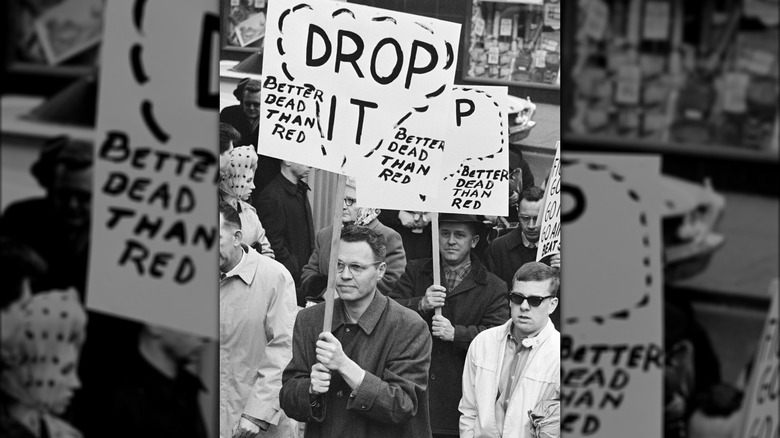

When it comes to unjust conflicts the United States got involved in, few were more messed up than the Vietnam War. Despite it being a more modern conflict, with plenty of photos and videos taken by journalists who covered it, the war was such a ridiculous quagmire that very little that we know about it is straightforward. Major moments are shrouded in mystery, with historians forced to try to piece together what happened despite many records still being classified. There's also the fact that some events were so horrific that different groups who were involved tell differing stories, trying to pin the blame on someone else.

It all adds up to a confusing war with no clear reason, murkily lurching along from terrible event to terrible event in the jungles of Southeast Asia for a decade, before ending in seemingly the worst way possible. Here are some of the things about the Vietnam War that still don't make sense decades later.

What really happened in the Gulf of Tonkin?

The Vietnam War did not start out as the United States' conflict. While the U.S. government had supported the Southern Vietnamese president during the Kennedy administration, it wasn't until 1964, under Lyndon B. Johnson, that Congress authorized escalating the country's military presence in Southeast Asia. That change in policy was directly in response to an incident in the Gulf of Tonkin — but much of what was believed at the time about what happened there is now doubted by military historians.

What we do know is that on August 2, 1964, the USS Maddox fired on two small North Vietnamese boats in its vicinity. It is not clear if the boats intended to attack, but it is likely. Two days later, the Maddox, now accompanied by the Turner Joy (pictured), saw signs on its radar that the crew interpreted as more boats. The ship's intelligence officer also received messages that he interpreted to mean an imminent attack. However, when President Johnson was told this information, he ordered retaliatory bombings, regardless of the fact that no attack had actually happened yet. It would later emerge the intelligence officer was probably mistaken and that the dots seen on the radar were not boats, let alone ones shooting dozens of torpedoes at them, as the sailors first believed.

In 1995, former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara met retired General Vo Nguyen Giap and asked if the second attack on August 4 had actually occurred. The general said no, it had not.

Why were U.S. soldiers given malfunctioning weapons?

If you have seen images of U.S. soldiers in Vietnam, you will probably have seen them carrying an M16 rifle. This was the standard issue weapon for the troops arriving in that country as early as 1965. The problem was that, while the M16 was supposed to give U.S. troops a fighting chance against the North Vietnamese's powerful AK-47s, in actuality, they were a disaster on the battlefield.

Soldiers found themselves saddled with a weapon that jammed, failed to eject its cartridges, and needed to be fixed in the middle of battle. While they believed the weapons were essentially self-cleaning, this was untrue, and even less accurate in the humid climate of Vietnam. Morale plummeted, and parents on the home front complained to Congress about their sons' useless weapons.

The big question is: did the U.S. government know all this before and while they issued the M16 to their troops? Many signs point to yes. The M16 failed some of the tests it was placed in before being selected as the military's new weapon of choice. The fact that it was picked anyway might be because of how closely related it was to the M14 — the rifle it was replacing. The Pentagon was allegedly resistant to change, so going with something similar, even if it was wrong for the troops, made sense to them. It wasn't until around 1968 that the M16 got the necessary improvements to be useful in Vietnam.

Why did Operation Marigold fail?

Undoubtedly, one of the most bizarre unsolved mysteries of the Vietnam War was the peace talks known as Operation Marigold. To this day, very little is known about how this attempt to end the war in the 1960s began, how it progressed, or why it failed. What does seem clear is that of all the hundreds of failed attempts at peace, this one came closest to actually having a chance at success.

The operation was spearheaded by diplomats from Poland and Italy, as well as a bit of quiet involvement from the Soviet Union. The main figure was Polish diplomat Janusz Lewandowski. Poland was a communist country at the time, so it had direct links to North Vietnam. The U.S., on the other hand, did not have any diplomatic relationship with the Asian country, and both sides refused to change that until the other would compromise. Of course, neither side would.

But thanks to Lewandowski's work, the U.S. and North Vietnamese ambassadors to Poland agreed to meet in Warsaw in 1966. Days before this historic meeting was to take place, the U.S. resumed bombings around Hanoi. Why this happened is unclear; it has been blamed on simple incompetence. There was also a miscommunication about where the two men were supposed to meet. As a result, the planned meeting never happened and the war continued for seven more years.

[Featured image by Mateusz Opasiński via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Why didn't Richard Nixon end the war sooner?

By the time Richard Nixon became president of the United States in January 1969, it was clear the Vietnam War was not going well for the U.S., perhaps even unwinnable. Yet Nixon didn't move to end his country's involvement until well into the 1970s. Why? Why wait and allow thousands more men to die in a war that had no clear goals or path to victory in a country on the other side of the world?

It's possible this was all because of Nixon's desire for power. The Vietnam War had already brought down one president, forcing Lyndon B. Johnson not to seek another term when it became clear he was far too unpopular to win. Nixon was afraid that when U.S. troops left South Vietnam, it would immediately fall to North Vietnam, which would reflect badly on him. Therefore, while he did reduce the number of U.S. troops in the country significantly, he did not talk about leaving altogether until he won reelection in 1972. That way, whatever horrible things befell the South Vietnamese after America pulled out, Nixon knew he couldn't be punished for it at the ballot box.

Nixon would occasionally second-guess this decision for being too evil — allowing men to die for no reason to stay in power was hard even on his conscience. But his secretary of state was Henry Kissinger, who had no such qualms. Kissinger made sure Nixon stuck to the plan.

How could the My Lai Massacre have happened?

March 16, 1968 saw one of the lowest moments in U.S. military history: the My Lai Massacre. Soldiers belonging to Charlie Company, 11th Brigade, Americal Division entered the My Lai village and killed 300 unarmed civilians, including women and children. Not everyone in the village was slaughtered, and there are many disturbing firsthand accounts from survivors of the My Lai Massacre. There was no way to legitimize the slaughter as an acceptable part of war; it was murder.

While people expect soldiers to kill enemy combatants, the world was shocked when they learned what occurred at My Lai over 18 months later. Despite the horror, only one soldier was convicted for his actions in the village: Lieutenant William L. Calley was sentenced to life but released on appeal in 1974.

One of the questions that remains is how something like this could happen. Blame for the massacre was placed on seemingly everyone and everything. The soldiers said they had been given permission by their commanding officers. Charlie Company had lost several members to mines and boobytraps over the previous months, while not succeeding in engaging the enemy. They were frustrated and had already murdered one civilian woman in anger. There was the fact that Ivy League graduates didn't sign up to fight, thus, the logic went, forcing the military to draft less intelligent men to lead. And Calley was said to have been bullied relentlessly by his commanding officer. All of this built up to something horrific.

Who ordered the killing of a Vietnamese double agent?

War is hard enough for soldiers without getting the covert intelligence community involved, which is when events can get really out of hand. Unfortunately for those of the public curious to know about government failings, the CIA is pretty much allowed to quash investigations into their dealings in the name of national security. That's seemingly what happened with what became known as "The Green Beret Affair."

This event involved the U.S. Army and the CIA, but both blame the other for what occurred. What we do know is this: On June 20, 1969, a Vietnamese man going by the name Thai Khac Chuyen was drugged by several Green Berets, taken out into the South China Sea in a boat, shot in the head, and his weighed-down body dumped overboard. The reason for this extrajudicial killing? Chuyen was supposed to be assisting the U.S. forces but was suspected of being a double, or possibly even triple, agent.

Eight Green Berets were eventually arrested for Chuyen's murder, but the case against them fell apart when the CIA refused to let any of their employees testify. It turned that, while Green Berets do not normally fall under the CIA's purview, in this case, they were working for them. However, the CIA denied they told the men to eliminate the alleged double agent, nor even that they had heard of him before. The men accused, on the other hand, said the CIA made it very clear Chuyen needed to die.

How close did the US come to using nuclear weapons in Vietnam?

There's no doubt that whatever happened in Vietnam during the war was worse than you thought, but the one small silver lining is it never went nuclear-war-level bad. Not for lack of trying on the part of some in the U.S. military, though. In 1968, General William Westmoreland was in charge of the military in Vietnam. He had long planned for a major battle — one he hoped would be a turning point in the war — to take place at a location called Khe Sanh. But when the North Vietnamese finally attacked the location, U.S. troops had to be pulled away just days later to defend against the slew of attacks now known as the Tet Offensive.

Westmoreland refused to abandon his original plan for Khe Sanh, however. Rather than lose the strategically important location, he wanted to use tactical nuclear weapons — or at least have them on hand in case they became necessary. He worked with other generals in the Pacific theatre on a plan to move nukes from Guam into the jungles of South Vietnam, codenamed "Fracture Jaw."

The problem was that the generals involved hadn't bothered to ask their commander-in-chief what he thought of the plan. When Lyndon B. Johnson learned what was up on February 2, 1968, the operation was well underway and he was furious. Despite this, the generals in Asia continued planning for another 10 days before finally ending work on Fracture Jaw.

Did the government know the dangers of Agent Orange?

Fighting traditional wars is almost impossible in the thick jungles of Vietnam. Rather than adapt to the terrain, the U.S. military attempted to change the landscape completely by dropping what were known as the "rainbow herbicides" (the most infamous of which was Agent Orange) on the country to clear huge areas of vegetation. Called Operation Ranch Hand, it was a huge success when it came to killing plants, but had the tragic consequence of also killing people. Operation Ranch Hand resulted in devastating effects for both the Vietnamese population and U.S. troops.

Dow Chemical and the other companies who produced the rainbow herbicides are certainly touchy about their involvement. To this day, Dow has an official statement on their website saying they were forced to make the herbicide due to the Defense Production Act, and that it is all the military's fault for the terrible health problems that it caused. However, there is evidence these companies hid how dangerous Agent Orange was from the government.

By 1965, internal documents show that Dow knew that Agent Orange's ingredient, dioxin, was toxic. They then organized meetings with the other companies producing it to discuss how toxic it was. Yet, they did not tell the government and publicly claimed the herbicides would not harm humans. Not only that, but almost a decade earlier Dow knew how to lessen the amount of dioxin in Agent Orange without affecting its herbicidal abilities and just ... didn't do it.

Were any POWs left behind?

Life for a soldier during the Vietnam War was rarely, if ever, fun, but those U.S. troops who were taken prisoner had it far worse. POWs (one of the most famous of whom was future-Senator John McCain) were regularly tortured and kept in appalling conditions. Many died, but others were lucky enough to make it home, including the joyous former POWs pictured above being transported home from Vietnam in 1973.

But did all the POWs who were alive by the time the U.S. left Vietnam in 1975 actually make it back? One conspiracy theory that the U.S. government knowingly abandoned POWs in Vietnam was so widespread that it was the basis of the plot for 1985's blockbuster sequel "Rambo: First Blood Part II." This conspiracy wasn't created out of thin air, as there are many soldiers who went to Vietnam and remain unaccounted for. As of 2022, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) listed 1,244 Americans as still unaccounted for in Vietnam. However, almost 500 of those individuals are considered "non-recoverable," meaning there is evidence pointing to the fact they died, but it can't 100% be proven because finding their remains may not be possible. In 2023, four more sets of remains were recovered and identified, with the U.S. government promising not to stop searching.

Not everyone accepts this as the reason some soldiers are unaccounted for, however, including Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Sydney Schanberg. He accused the government of ignoring thousands of first-hand accounts that POWs were still alive in Vietnam after the war ended.

Why was Gen. John Lavelle blamed for approved bombing raids?

General John D. Lavelle commanded the Seventh Air Force in Vietnam and in 1972, it appeared the campaigns he was leading were doing well. So it was shocking for him when he was suddenly told to return to the U.S. He was fired, hauled in front of Congress to be dressed down, and demoted two stars before being forced to retire. He died seven years later, but well into the 21st century, his family still had questions about what exactly happened and why he was punished.

Lavelle wanted to make sure more of his pilots came back from bombing missions alive, so he asked that the rules of engagement be made a bit looser. Lavelle claimed he was told that was fine, but for various political reasons this could not be put in writing. His version of events is backed up by several tapes recorded by President Richard Nixon in the Oval Office.

After a misunderstanding of one of his orders, Lavelle was accused of telling his subordinates to falsify reports to make their bombing raids look legal if they weren't, even under the looser rules of engagement. While Nixon is also on tape expressing anger at what was happening to the general, Lavelle was thrown under the bus by his superiors. Why? One possibility is they were trying to keep any information about other bombing raids — specifically the secret ones in Cambodia — from reaching the public.