Strict Rules Women Had To Follow During World War II

For many of the countries and peoples involved, World War II was an existential struggle, uprooting populations (or worse), shattering cities and landscapes, and threatening even worse outcomes depending on which belligerents prevailed. It was a world war in the sheer number of countries participating, willingly or unwillingly, but also in the enormous masses of human beings who took part, as armies moved across and between continents and entire economies were adapted to serve the needs of nations at war.

Women were central participants in the war. Some fighting forces enrolled women as combatants, while many more used them in support roles. Women who remained at home filled roles as laborers that had been left empty as men left for the front. And of course, women had to endure the indignities of defeat and occupation if their countries fell. For many women, the centrality of the war in daily life came with rules they had to follow for their own safety, the safety of those they loved, and to help ensure their side was left standing when the smoke cleared.

Have many children (Germany)

While women participated in the Nazi project at nearly all levels, they had one ability that even the most fervent male Nazi would always lack: the power to give birth to the next generation of Aryan children. Though men and women were both encouraged to reproduce (if racially "pure"), mothers were especially valued in Nazi thought and policy, as it was through them that the ostensibly pure and superior race would grow and become more powerful. Additionally, in their traditional roles as homemakers and child-rearers, women were well placed to instill in their children the ideals of Nazi Germany from the cradle.

Prolific mothers under Nazi Germany, provided they and the children's fathers were racially and ideologically acceptable, were eligible for military decoration. The "Gold Mother's Cross" rewarded women who had at least four children, with the highest grade going to those who produced and reared eight or more children for the Reich. By the time the last Mother's Cross was awarded in 1944, over 4.7 million of these recognitions of "correct" fertility had been awarded.

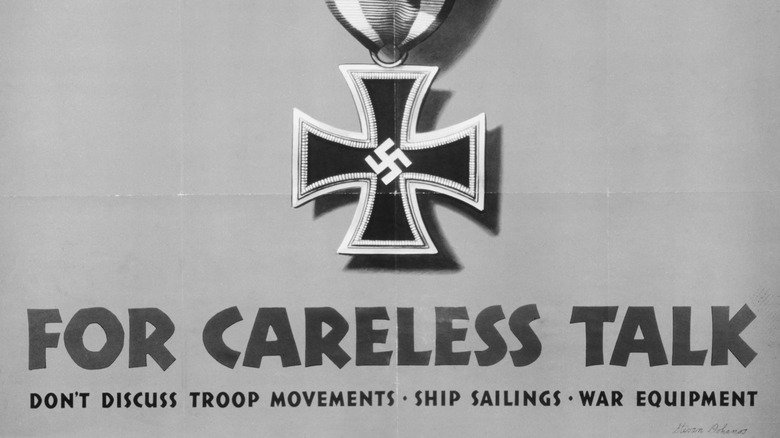

Keep quiet (United States and Allies)

Espionage was a serious concern during World War II: with armies slugging it out across Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific, any bit of extra information that could strengthen your own side's odds of victory was highly valued. Domestic propaganda campaigns in the United States and its allies emphasized the danger of discussing army movements, war work, or anything that could conceivably be of military use to Axis operatives. "Loose lips might sink ships" in the United States and "careless talk costs lives in the United Kingdom" were popular, government-approved slogans encouraging citizens to button their yaps to beat Hitler.

While these campaigns were not exclusively aimed at women, the outsize presence of women on the home front meant that they were generally the main recipients of the message. Women working in factories, receiving letters from their men abroad, or home from their own deployments could all have information the Allies didn't want in Axis hands. Cautious women were made well aware that the best thing to say about their war work was usually nothing at all.

Make the enemy lose hope (Axis)

As Allied troops resisted Axis expansion in the European and Pacific theaters of the war, the Italian, Japanese, and German governments attempted to sap their will to fight by broadcasting disheartening propaganda. English-speaking broadcasters, often female, taunted servicemen over the airwaves about the difficulties they would face in their efforts to defeat the Axis, using insidious attempts to plant doubts about whether their wives and girlfriends back home were really remaining faithful, interspersed with popular American songs intended to cause homesickness. Multiple women performed these broadcasts, though they were collectively nicknamed "Tokyo Rose" in the Pacific and "Axis Sally" in the West.

After the war, three women became the faces of these broadcasts. Mildred Gillars (pictured above), an American citizen and failed actress broadcasting from Berlin, was convicted of treason and served twelve years before retreating to a convent in Ohio. Rita Zucca, who had renounced her American citizenship and transmitted from Italy, served a short sentence in Italy and was never allowed to return to the United States. Iva Toguri D'Aquino, an American who had been living in Japan when war came, was one of the most infamous "Tokyo Rose" broadcasters and was later convicted of treason, though she was later pardoned after decades of contentious legal wrangling. D'Aquino's defense was that she had intended to parody the propaganda and had no intention of supporting the imperial Japanese cause.

Entertain the troops (United States)

During World War II, leaders wanted armies (and nations) with high spirits and confidence in victory, so morale was a serious concern for all parties. To this end, the United States established a system of entertainment to brighten troops' deployments, whether they were stationed at home or overseas. Both big names and lesser-known talents sang, danced, told jokes, and brought much-needed levity and relief through the famous "USO Shows." This was no safe gig: 37 American entertainers died during their war work, and at least two suffered brief German captivity.

Among the most famous entertainers to make the tour was Marlene Dietrich. The elegant German actress and chanteuse had left her home country to pursue a career in Hollywood, then refused to return to Germany to perform after it had come under Nazi control, despite express requests from Hitler himself. In addition to her secret work as a spy, Dietrich performed hundreds of times for Allied troops working to purge her homeland of the Nazis, often performing close to the front. Fate rewarded Dietrich for her physical and moral courage with the honor — and doubtless pleasure — of announcing the D-Day invasion to her audience during a performance in Italy.

Fill farms and factories (United States and United Kingdom)

Rosie the Riveter became an American icon for good reason. With much of the male labor force having enlisted, women worked outside the home in greater numbers than ever before. Not only had men vacated many positions, but new jobs were also emerging, with the American economy repositioning itself to supply the enormous demands for weapons and supplies that a conflict on the scale of World War II required. Factories producing materials, weapons, vehicles, and more were increasingly staffed by women, as did farms growing the food needed to feed Americans both at home and fighting abroad.

Women doing war work faced challenges, including sexism from men remaining in the workforce and, at times, their own ideas about women's correct roles in society and the economy. Nonwhite women endured racism and, once the war was won, many female workers were let go in order to "free up" their jobs for returning men. Despite these factors, the experiment of women's wider participation in the economy was a success. Not only did American industrial might help bury the Axis powers under a level of materials and munitions they simply couldn't match, but the money women made (and often saved) during the war helped spur postwar prosperity. Additionally, a cultural shift had begun, and more and more women would work outside their homes in future generations.

Enlist and fight (United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union)

Many women's involvement in the war was as direct as it gets: they enlisted in the armed services of their respective countries. To an extent, the reason for this was similar to the arguments for women working in agriculture and manufacturing on the home front. Any supply, support, or medical job handled by a woman theoretically freed up a man to head to the front and fight. Over 640,000 British and 350,000 American women served their country in uniform through a variety of programs designed to enable women to enlist.

The Soviet Union went one step further. Given both the desperation of its resistance to the Nazi invasion of its territory and the striven-for socialist ideal of gender equality, Soviet forces became the first regular armed services to enlist women as fighters. Soviet women flew aircraft in combat missions, crewed tanks, and served with particular effectiveness and distinction as snipers. One Soviet sniper, Lyudmila Pavlichenko, notched 309 confirmed kills before injury forced her retirement from the front; afterward, she toured the United States to bolster support for opening a second front in Europe, which would relieve pressure on Soviet forces. In Chicago, Pavlichenko told a rapt crowd: "Gentlemen, I am 25 years old and I have killed 309 fascist occupants by now. Don't you think, gentlemen, that you have been hiding behind my back for too long?"

Improvise with beauty and fashion (United States, France, United Kingdom)

With perennial fashion center Paris under Nazi control, British and especially American designers had a bit more creative freedom to operate outside the French shadow. However, that liberty was restricted by shortages and rationing of certain materials, as fabrics were needed by the armed forces both for uniforms and for supplies like parachutes. The British "utility dress," available with ration coupons, was so flatteringly simple that even non-rationed clothing came to follow a similar aesthetic. Sequins, also unrationed, added some brightness that anyone in that nervous period might have appreciated. (After the war, with fabric supplies returning to normal, Christian Dior's full-skirted New Look put Paris back at the top of world fashion.)

Until shortly before World War II, women's stockings were usually made of silk, with nylon options entering the American market in 1939 and becoming very popular — just in time to become scarce as war demands ate up the fabric supply. To replicate the look of stylish nylon stockings, women painted their legs (or had them painted, for the less agile), sometimes including a darker pencil "seam" down the back of the leg to complete the illusion. Nylon lovers were rewarded for their patience: less than two weeks after Japan's surrender in August 1945, DuPont was again cranking out nylon for legwear, though it could not immediately meet the pent-up demand.

Commit crimes against humanity (occupied Europe)

It is impossible to discuss World War II without addressing the mass killings that took place in occupied Europe. The Holocaust of European Jews and the hand-in-hand exterminations of queer people, handicapped people, and other ethnic minorities continues to shock the world due to its brutality and the sheer scale of the operation. Women participated in these campaigns as camp guards, with several later tried for their actions during post-war trials.

Among the most notorious of Hitler's female concentration camp officers was Irma Grese, whose youth and physical attractiveness made the allegations against her more shocking. A shy farm girl, Grese became a committed Nazi believer as a teenager and in 1942, at the age of 18, she began training to serve as a prison guard. She excelled in the eyes of the Nazis and was transferred to Auschwitz. In addition to the psychological tortures survivors reported, she personally beat, whipped, and set dogs upon prisoners under her control. Grese was even responsible for selecting people to be sent to the gas chambers to be murdered. Captured in the spring of 1945 as Allied armies strangled Germany, Grese was convicted before a British tribunal and sentenced to death for her crimes, dying at the end of a noose at 23.

Represent the nation in exile (Luxembourg and the Netherlands)

Royal families of countries in Hitler's way had two real choices: stay in their countries and share their people's hardships whilst risking death, or flee, risking accusations of cowardice but remaining free to serve as a symbol of the nation's future and unity. Two of the monarchs who faced this choice were Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands and Grand Duchess Charlotte of Luxembourg. Both left their countries during the war, served as potent national symbols during occupation, and returned in triumph after the German defeat.

Grand Duchess Charlotte took over from her sister, Marie-Adélaïde, in 1919, as Marie-Adélaïde had become unpopular due to her perceived accommodation of German occupation during World War I. When neutral Luxembourg was invaded by Germany, the Grand Ducal family fled. Charlotte spent the war primarily in Canada and the United Kingdom, meeting U.S. President Roosevelt several times and broadcasting messages to her people in Luxembourg. Both her husband and son fought under the British flag, and Charlotte returned to Luxembourg in 1945 to reign for another 19 years.

Queen Wilhelmina's story was similar. Having reigned since 1890, she had steered the Netherlands' neutral course through World War I, but was unable to keep the Nazis from overrunning the Netherlands in 1940. From England, Wilhelmina broadcast regularly to her people to keep their spirits up and was enthusiastically welcomed home upon the country's liberation. The Netherlands remained headed by a woman for decades after: Wilhelmina was succeeded in 1948 by her daughter, Juliana, who was in turn succeeded in 1980 by her own daughter, Beatrix.

Resist enemy forces (Occupied Europe)

During World War II, countries defeated by the Axis powers did not always submit quietly. While resistance activities had to be carefully balanced against the danger of reprisals by occupying forces, citizens of occupied countries could and did sabotage, undermine, and frustrate the activities of their enemies. Resistance forces arose throughout occupied Europe but were especially strong in France and Yugoslavia, and in both countries, women were active participants.

French women served both in support roles such as administrative work and as active agents, smuggling weapons, sabotaging German communications, and helping people in danger escape occupied Europe. Allied airmen shot down over France were sometimes rescued and aided by local women, who are often anonymous to history given that it was safer to use false names. Yugoslavian women were, if anything, more ferociously opposed to German occupation, with their roles not limited to support and espionage but including the possibility of active combat with partisan resistance groups. They also organized ways to keep the local population fed during the war, forming units to perform harvesting work and prevent Axis forces from stealing the crops. Yugoslav women were both rewarded and punished for their resistance: over 100,000 received decorations of merit for their actions, but over 600,000 were killed, representing over a third of Yugoslav deaths.

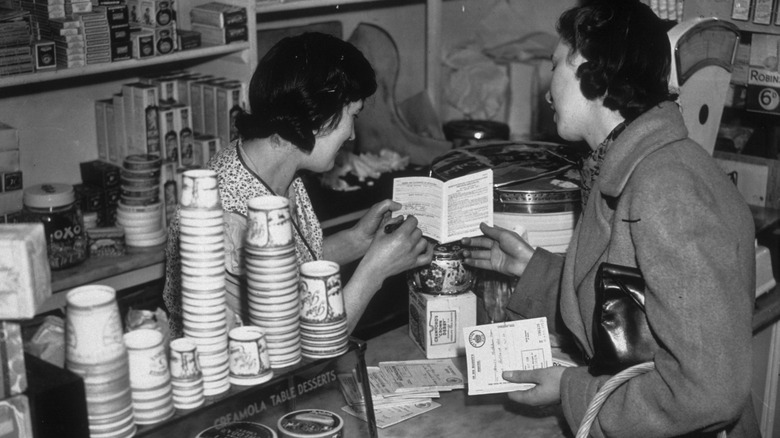

Get creative with rationed supplies (United Kingdom)

By the time war seemed probable in the mid-1930s, the United Kingdom was a net importer of food, meaning that both local consumption and the British ability to supply forces abroad could be threatened by disruptions to international trade. The British government built up stockpiles in the years before World War II began in Europe, but nevertheless, food rationing began in January 1940. The first commodities to be rationed were butter, sugar, bacon, and ham, and by the Axis powers' zenith in 1942, nearly all foods were rationed: fresh vegetables, fruit, and fish were not, and bread was not rationed until after the war. Rationing also governed the use of other consumer goods like gasoline and clothing.

Homemakers, primarily female in the 1940s, had to think creatively and practice smart home economics to keep their families fed during the war. Each person had an allotment of points, which varied according to individual circumstance (expectant or nursing mothers or those with physically demanding jobs got more). Gardening, at home or on shared public land, could supplement a family's portions, as could purchases on the black market, for those with the right connections who were willing to pay the inflated prices these sneakily provided goods could command.

Adjust to a new society (Japan)

At the war's end in 1945, women across the globe found themselves facing a world much changed over the course of the conflict. While they all faced adjustments, perhaps the biggest adaptations were required of Japanese women. The conservative Japanese society that had brought the empire into World War II had lagged behind other participating countries in enlisting women for war work, but by the war's end, over 4 million Japanese women were working in important industries. Proportionally, this was a lesser number compared to the United States, but was still a large and culturally significant number.

Surrender found a Japan badly damaged from bombing, chronically short of food, and occupied by the very culturally different United States. On paper, this led to Japanese women gaining rights: they could vote from December 1945, and the April 1946 constitution enshrined gender equality, though cultural attitudes did not necessarily keep pace with legal changes. Some Japanese women formed relationships with men in the occupying forces and married them, becoming "war brides" and returning with their husbands to the United States. Though these women initially faced racialized barriers to immigration, by 1959, Japanese wives of American servicemen had increased the Asian-descended population of the United States by 12%.