The Legend Of Lady Godiva Finally Explained

Even if the name first calls to mind chocolate before it actually makes you think of that weird tale of nudity, horseback riding, and voyeurism, you've certainly heard of Lady Godiva. But the old tale of Lady Godiva isn't as much a part of collective consciousness as it once was, and you may not know all the details of the story.

You probably know that Lady Godiva was a streaker, though, although she was more modest than most streakers since she had the whole hair cloak thing to help her out. But was Lady Godiva a real person, or was she just a figment of someone's weird imagination? Did she really ride naked through the streets of Coventry in England? And if so, why? And was she really like a racing car passing by? Here's what you need to know about the legend of Lady Godiva. Yes, need to. It's important stuff.

Lady Godiva was a real person

The answer to your first question is "yes." Lady Godiva was a real person. According to History, she lived in 11th century England and was married to a powerful earl by the name of Leofric, who ruled Mercia and Coventry. But the historical Godiva really didn't do much of note, because the local histories barely even mentioned her. She appears to have had at least one son, Alfgar, who became Earl of East Anglia. She also had a granddaughter named Aldgyth or Edith, who went on to marry King Harold II and become queen of England — at least temporarily, since Harold died rather spectacularly at the Battle of Hastings just one year after their wedding.

So Godiva's legacy — the accurate one — is really just in her progeny, which is kind of how things went when you were a woman in the middle ages. No matter what you do, people really only remember the deeds of your husband, your sons, or the men your daughters married. So Godiva might not have been noted much by contemporary historians, but that doesn't necessarily mean she wasn't noteworthy. It's just that no one wrote down most of the things she did, so we'll never really know.

Lady Godiva's name wasn't really "Godiva," and she wasn't a lady

Godiva is a name that has sort of evolved over the centuries, probably because it sounds nicer than her real name, which was "Godgifu." Godgifu means "good gift," but it's kind of a mouthful. Imagine eating a piece of Godgifu chocolate.

Godgifu wasn't only not Godiva, she also wasn't a lady. According to How Stuff Works, in 11th century Anglo-Saxon England, an earl's wife would have boringly been referred to as "the earl's wife," or even "the earl's bed-partner." So just in case you were still on the fence about whether the people of those times tended to suppress the accomplishments of women or not, well, imagine if your title was based not just on the person you were married to but what the two of you did at night when the lights were out. Nice.

In Godiva's time, "Lady" was reserved for the queen and the queen alone, so Godiva's granddaughter would have briefly been "Lady," but Godiva herself would not have used that title. So her true and accurate name and title would have been Leofric Eorl's Gebedda Godgifu. Now put that on a piece of chocolate.

Lady Godiva seems to have been a generous and pious person, just as the story describes

There are a few tantalizing pieces of information in the historical record about the real Lady Godiva. According to the BBC, Godiva and Leofric founded a Benedictine monastery for 24 monks and an abbot. The monastery was on the site of a nunnery that had been destroyed by Danes in 1016.

Godiva must have been a pretty pious person because it's said that she had all of her gold and silver melted down and remade into images of saints, crosses, and other objects, which she donated to the monastery. On her deathbed, she gave the monks a gem-encrusted gold chain and told them to put it around the neck of an image of the Virgin Mary. Anyone who came to the abbey church was supposed to say a prayer for each stone in the chain. So she was basically just increasing the workload for all the pilgrims who came to her church, but whatever. Everyone knows the Virgin Mary was all about fancy jewelry. Wasn't she?

Anyway, Godiva outlived her husband by a decade and was supposedly buried in the abbey church alongside him, though no one knows for sure if that's true. You can check out her potential final resting place for yourself, though, if you're interested. The remains of the monastery and cathedral can be seen in Priory Row, Coventry.

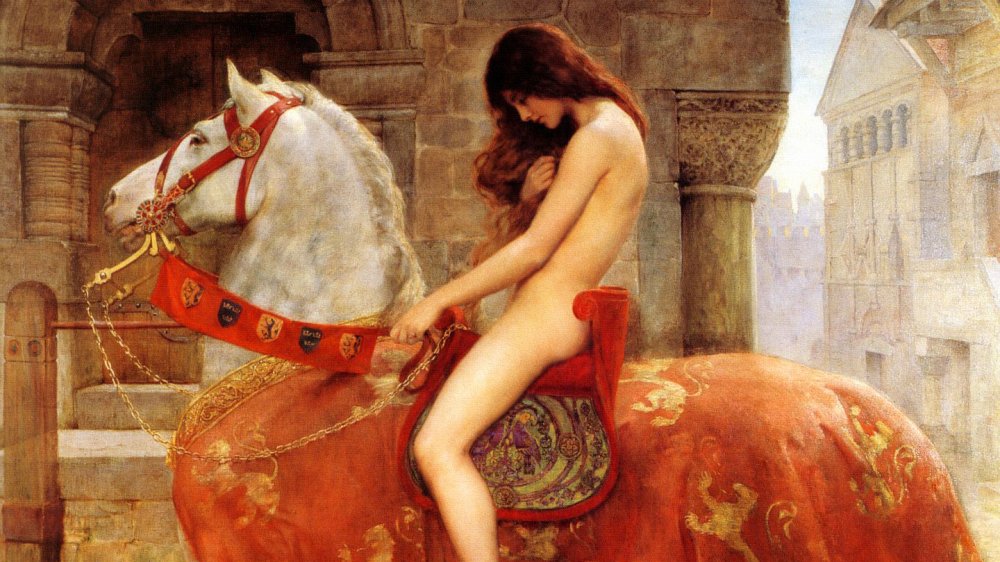

And now for Lady Godiva and the naked stuff

That's not why you're here, though. You don't care about someone's dusty old bones that may or may not be under some monastery or another. You want to hear about the streaking. It's okay. Everyone else does, too. And just in case you're not familiar with all the details of the story, it goes like this: Lady Godiva was troubled by the crushingly oppressive taxes her husband had levied on the people under his rule. She implored him repeatedly to lighten the people's burden, but he was a hard man and would not budge. Still, his wife pestered him until finally, in exasperation, he told her he'd lift the taxes when she rode naked through the town marketplace. So she did, though she had her long hair to cover up all the important bits.

Depending on which version of the story you're reading, Godiva was accompanied by a pair of soldiers or a pair of ladies. Out of respect, the citizens were asked to remain indoors and not look outside as she rode by. One guy did, of course, because there's always one guy who totally would (wait, only one?), but he was struck blind (or possibly dead) for his indiscretion. In the story, the peeker is called "Tom," which is where we get the expression "peeping Tom."

Upon Godiva's return, Leofric lifted the taxes and the citizens of Coventry, except for that one guy Tom, were forever grateful.

So is there any truth to the Lady Godiva story?

Sorry to disappoint you but there probably wasn't ever any streaking. There was no slow, naked ride through the streets of Coventry, either. That story didn't appear until a couple of centuries after the death of Lady Godiva, or if you prefer, a couple of centuries after the death of Leofric Eorl's Gebedda Godgifu. And if the story was at all true, well, it seems like it would have been the talk of the town at the time it happened, so the fact that a couple of centuries passed before it was ever mentioned in the historical record kind of calls its accuracy into question right upfront.

According to Britain Express, the story first appears in the chronicles of Roger Wendover, who was a monk at the Abbey of St. Albans. Roger wasn't exactly known for his stellar attention to historical accuracy, and the apparent source material was a little questionable, too — the abbey was at a major crossroads, so the story may have come from travelers en route to London, and even modern travelers don't usually tell super-accurate tales of adventure and nudity. Another strike against the story is that it describes a town with streets and a marketplace, and 11th century Coventry had neither — it was a farming community with a population of maybe 350 serfs. So that's disappointing but hey, at least we still have the chocolate.

Peeping Tom showed up centuries after Lady Godiva's death

So the story of Lady Godiva is 100 percent not-true, and that makes the Peeping Tom part of the tale like 150 percent not true because according to Harvard Magazine it didn't even show up in the story until well into the 17th century. And Tom's appearance in the legend really changed the entire scope of it — it went from a story of a noblewoman who made a selfless sacrifice for the benefit of the townspeople to a story about the evils of lust and the blessings of chastity. In Lady Godiva: A Literary History of the Legend, Professor of English and American literature and language Daniel Donoghue writes, "Over time, Tom would become the scapegoat and bear the symbolic guilt for people's desire to look at this naked woman."

And in case you needed more proof that the legend is just that — a legend — there's the issue of what happened to Tom after he peeked at Godiva. In Lord Alfred Tennyson's poem "Godiva," Tom's eyes "shrivell'd into darkness in his head, and dropt before him," which implies some sort of divine punishment. Generally speaking, stories that include divine punishment tend to be made up.

The Lady Godiva story may have had origins in ancient fertility rites

If you know anything about the pagan origins of Christmas and other beloved Christian holidays, you won't be surprised to hear that the Godiva story might have just been an adaptation of a very old tradition that existed in parts of Britain, Germany, and Scandinavia. According to British History, a naked woman riding a horse through a town or village may have been a representation of a fertility goddess in an ancient fertility rite — it's possible that the "peeping Tom" part of the story came from this old tradition, too, since in some of these fertility rites there was a male sacrifice that ensured the fertility of the community's crops and animals. The ritual itself may have morphed into a play or symbolic procession over the years, and it was probably pretty shocking for Christians like Roger Wendover and those who came before him.

Sometimes, though, those pagan rituals and stories had such a strong pull on the people the Christians were hoping to convert that instead of trying to erase them, the church would simply turn them into something that aligns with Christian values. So it's possible that the story was simply co-opted by the monks who later wrote it down — instead of a pagan fertility goddess riding through town in order to promote the well-being of crops and animals, it was a pious lady who was making a great sacrifice for the well-being of her people.

Taxes didn't really work like that in 11th century England

Some of the historical details are a bit off, too. In the real Godiva's time, taxes didn't work quite the way that the legend seems to describe them. According to How Stuff Works, Godiva owned Coventry before she married Leofric, which means that she would have had the power to reduce taxes there without having to seek his permission. The idea that the noble lady had to implore her husband to lower taxes in her own lands smacks of later property laws, which decreed that upon marriage, a woman's land automatically became the possession of her husband.

Also, during the 11th century, Coventry was just a small piece of farmland, probably too small to even warrant taxation. In fact an inquiry made in the time of Edward I seems to support that there were no taxes paid in Coventry at that time, with the exception of a tax on horses. And while some people think that's evidence that Leofric lifted taxes after his wife's naked ride, it's more likely to just be a reflection of the fact that there was really nothing in Coventry worth taxing.

So a naked ride would have been glorious but it also would have been pointless. It's unlikely that a noblewoman would have subjected herself to such a thing for a cause she truly believed in — it's laughable to think she might do it for no reason at all.

Here are a few what-ifs

Some sources think that there could be some small basis in truth to the story — they mention the ties between the Abby of St. Albans, where Roger Wendover lived, and the abbey in Coventry that was founded by Godiva and her husband. According to Great Tales from English History: The Truth About King Arthur, Lady Godiva, Richard the Lionheart, and More, the monks would have traveled between the two monasteries for study and prayer, and it's possible that Roger may have seen some long-since lost manuscript mentioning Godiva's unconventional plan for community tax relief.

The story could possibly have had political motivations as well — perhaps Roger sought to glorify the benefactors of Coventry's abbey with a tale of piousness and sacrifice. Everyone in that original story comes out looking pretty heroic, even Leofric who proves to be an honorable man, true to his word, who comes around in the end and gives the people what he's promised.

Some historians also wonder if the story might not refer to literal nudity. Perhaps the manuscript that Roger was working from only mentioned "stripping," which could refer to Godiva's jewelry and other finery. A noblewoman riding through town dressed as a peasant would have made a strong statement on its own, no nudity required. So if you like this story and you want it to be true, well, there are a few tendrils to cling to.

The Lady Godiva story is full of contradictions

Like all old tales that somehow make it into modern consciousness, the original story of Lady Godiva has morals and ethical quandaries meant to inspire reflection in the listener. According to Harvard Magazine, the story is full of the sorts of contradictions that make for great myth — an obedient lady who, at the same time, opposes the oppressive taxes her husband has levied on the common people. A pious lady who rides naked through the streets. A noblewoman who cares about the common people. Godiva has all the qualities of a heroine — a person who can walk that fine line between corruption and virtue and always come out on the side of virtue. In a way, Godiva sets an impossible standard, the sort of thing everyone knows they should aspire to but will probably never really achieve.

The Peeping Tom element of the story adds another layer of moral consequence to the tale. Once that storyline was added, it became a warning against temptation and sexual deviancy, which at that time was basically anything that veered from missionary position in the dark.

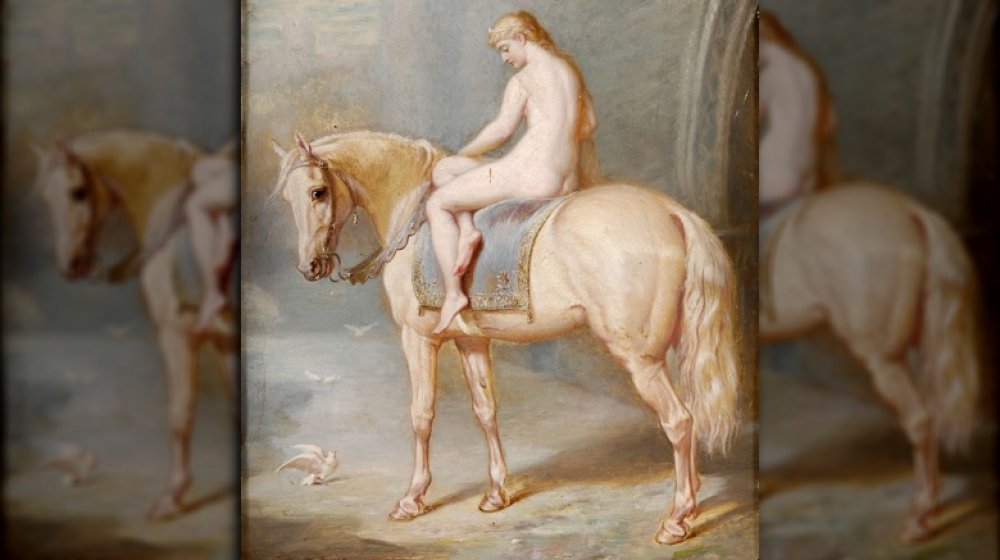

Archaeological evidence supports the long hair part of the Lady Godiva story

Weirdly, the truth about lady Godiva's appearance seems to match the legend about her naked ride through town. Many versions of the story say she had long, golden hair, and now archaeological evidence suggests that is actually true.

According to the Telegraph, monasteries in the middle ages often put stained glass portraits of their benefactors on the west side of the building. Godiva's monastery at Coventry was destroyed during the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1500s, and so was a stained glass portrait on the west side of the building, presumed to be a portrait of the monastery's benefactor. When archaeologists pieced it back together, it showed the image of it a woman with very long, golden hair. Archaeologists don't believe the portrait shows the image of a saint, since there is no halo or headdress, and its position on the west side of the monastery appears to imply that it is indeed a portrait of the monastery's benefactor. Since the image is clearly a woman, it's not a huge leap to conclude that it's a portrait of the real Lady Godiva.

So what does it mean that the hair in the portrait appears to precisely match the legendary hair of naked Godiva? Probably nothing, but it is still a pretty intriguing detail.

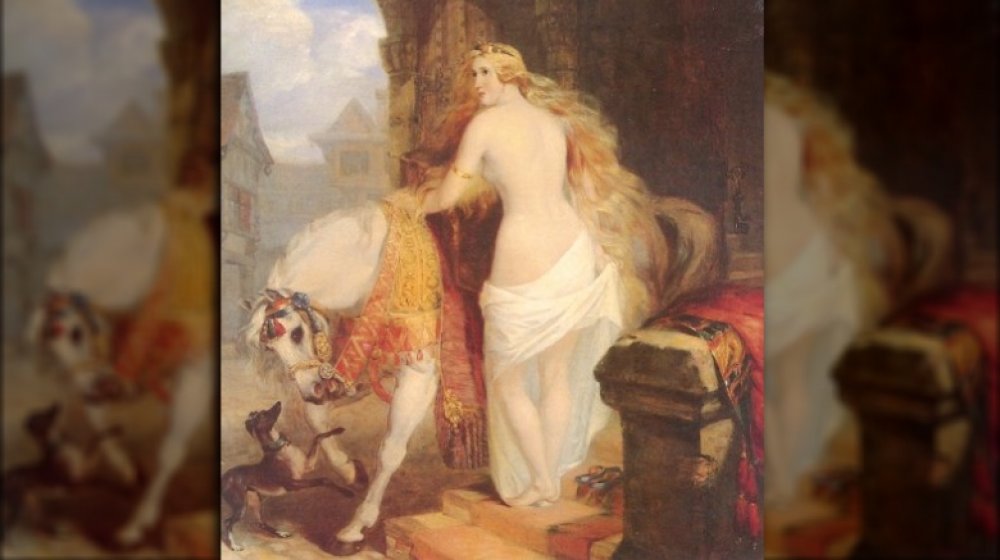

Coventry loves their local heroine

Fact or fiction, the town of Coventry loves Lady Godiva, and they've been holding an annual Godiva Procession off and on since 1678. It's not clear if the procession has always featured a facsimile of Lady Godiva as we all know her, or if it gradually lost its modesty over the years, but according to British History, by the 18th century and through the first half of the 19th century the procession included a young woman clad in a tight-fitting, flesh-colored costume. So no actual nudity, but still pretty, um, let's just say there were a lot of peeping Toms.

The event was popular with the townspeople but not so much with the church, and after the disastrous procession of 1842 where Godiva got so drunk she couldn't stay on her horse under her own power, the church started speaking out against the tradition. By 1900 it had ceased to be an annual tradition, and that's pretty much how it was until 1998, when the much less prudish modern town of Coventry decided to not only resurrect the tradition but also turn it into a "free festival of entertainment." Today's Godiva Festival includes three days of music and fun and attracts close to 150,000 people every year.