The Origins Of The Unholy Trinity Explained

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

The doctrine of the Trinity is easily one of the more recognizable, unique facets of Christianity. Distilled into the phrase, "One God in three persons," it was codified in Catholicism's Nicene Creed, which begins, "I believe in one God, the Father almighty," segues to, "one Lord Jesus Christ, the Only Begotten Son of God," and ends on, "the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life, who proceeds from the Father [and the Son]." The Triune Godhead doctrine is so self-evident to modern Christians that many don't give it a second thought.

But for something so fundamental and crucial to Christianity, it took hundreds of years to come together. After the Roman emperor Constantine converted to Christianity in 312 C.E., he called early church fathers to the First Council of Nicaea in 325 C.E. to solidify the tenets of religion's doctrine. Constantine's council failed on many points, and it took until Emperor Theodosius I in 381 C.E. to call the First Council of Constantinople to finalize the Nicene Creed and Trinity doctrine.

Even earlier than this, other church fathers like Irenaeus of Lyon (120/140 to 200/203 C.E.) in his text "Against Heresies" laid the groundwork for what would be commonly called "the unholy trinity." Derived almost exclusively from the Bible's apocalyptic final book, Revelation, the idea isn't official church doctrine. Focused on Satan, Antichrist, and False Prophet characters from Revelation 12 and 13, it took all the way to the 20th century to gain traction in the minds of the public.

[Featured image by Stefan Lochner via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

Early church fathers laid the groundwork

To understand the unholy trinity, we've got to understand a simple concept that comes with a big term: eschatology, or studies related to "the end of the days," as the Jewish Virtual Library says. Judaism has strong eschatological roots and believes in a final judgment and promised paradise, which are cited even in the Old Testament's first book in Genesis 12. This fundamental belief was transmitted to early Christianity, culminating in the writing of Revelation around 95 or 96 C.E, a book describing God's final judgment of humanity.

Christianity's early days were filled with loads of competing confessions (statements of belief, or schools of thought) that would later be considered heretical, like Arianism. Arianism stands out because it held that Jesus wasn't on par with God the Father, but was created by him — hence no Trinity as we know it. In this environment of early, uncertain doctrine, figures like Irenaeus of Lyons lived, wrote, and debated about ideas including Revelation. In "Against Heresies" (180 C.E.), he presents the events of Revelation as the culmination of an anti-God consortium driven by Satan. In "On Christ and Antichrist" (202 C.E.), Hippolytus of Rome similarly posits that Revelation's Antichrist is "a vessel of Satan."

Eventually, St. Augustine in "City of God" (413 to 426 C.E.) compared the "city of God" to the "city of man." The latter is ruled by Satan, a conniving creature bent on establishing an earthly, inverted parody of heavenly order. Augustine was the link for later theologians to envision Revelation's False Prophet and Antichrist as agents of Satan, making one unholy trinity.

Medieval investigations framed Revelation in real-world terms

It would take about another 1,500 years following St. Augustine for the notion of the unholy trinity to crystallize. Several Christian theologians carried on the work of investigating Christian eschatology (end times studies) through the medieval ages, especially Bede the Venerable (672/673 to 735 C.E.) and Joachim of Fiore (1130/1135 to 1201/1202 C.E.).

Bede the Venerable was among the first to try and interpret Revelation in a non-symbolic, concrete way in "The Explanation of the Apocalypse" (710 to 716 C.E.). In the book, he provides a blow-by-blow explanation of each chapter of Revelation, framing events in real-world terms. In Chapters 6 and 8, for instance, he describes the Antichrist as a kind of chief heretic guided by the devil, aka Satan, who leads a physical army against the Catholic Church. Bede paved the way for later thinkers like Joachim of Fiore to associate biblical characters with real-world analogues. And by Joachim's time — during the high Middle Ages (1000 to 1300 C.E.) — enough history had passed for him to look back and say, for instance, that Muslim leader Saladin was the sixth head of Revelation's dragon.

St. Thomas Aquinas built on these investigations in "Summa Theologica" (1266 to 1273 C.E.). Aquinas called the Antichrist a "member of the devil" and drew comparisons between Christ and God on one side, and the Antichrist and Satan on the other. And if there's two evil figures opposite the Trinity, then parity demands a third.

Protestant Reformation thinkers saw evil in threes

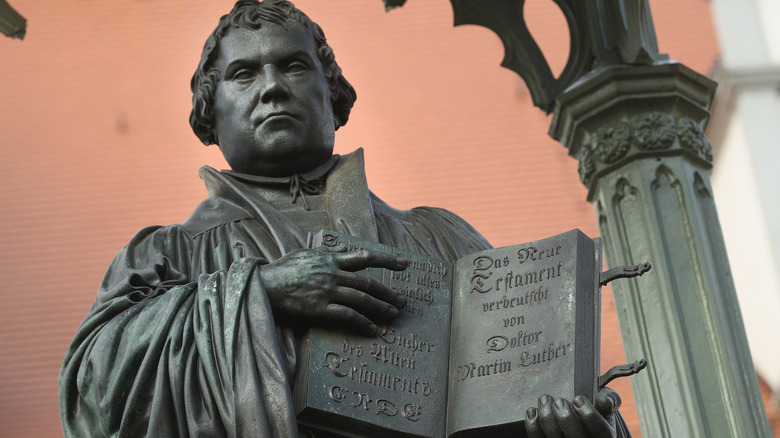

It wasn't until the Protestant Reformation (1517 to 1648) that Christian theologians began to use language that hinted at a formalized "unholy trinity." But this time, such language was used not to describe heretics fighting the Catholic Church, but the Catholic Church fighting the Protestant Church. This is particularly true of famed German pastor Martin Luther (1483 to 1546), who kickstarted the Protestant Reformation when he attacked the Catholic Church's selling of indulgences to grant forgiveness from sin.

In a nutshell, Luther compared the pope to the Antichrist. As WELS quotes, "This teaching [of the supremacy of the pope] shows forcefully that the Pope is the very Antichrist, who has exalted himself above, and opposed himself against Christ." Later on, as the Journal of the Adventist Theological Society quotes, Luther settled on the pope being the Beast from Revelation and the papacy being the Antichrist, both of which were appendages of Satan. Notice the trifold structure, like the Trinity.

Taking the baton from Luther, Protestant leader John Calvin (1509 to 1564) wrote a theological breakdown of Protestant Christianity in 1536's "Institutes of the Christian Religion." He goes the same route as Luther in presenting Catholicism as a three-part evil set against Protestantism. But, he defines "Antichrist" as more of a general, wordly sentiment running through nations rescued by Christianity like Italy, Germany, and England. More importantly, Calvin's branch of Protestantism — Calvinism — took firm root in the early United States. And it was here where the work of John Nelson Darby, the true progenitor of the unholy trinity, took off.

Enlightenment preachers spread the idea to the U.S.

Even though the European Enlightenment (1685 to 1815) was characterized by a shift toward rational, scientific inquiry, it also marked a renewed interest in figures from Revelation like the Beast, the Antichrist, and the False Prophet. This is due to the rise of "premillennialism," i.e., the belief that the end of the millennium would mark the long-awaited apocalypse described in the New Testament.

Even Sir Isaac Newton (1642 to 1727), one of the Enlightenment's most brilliant thinkers, was fascinated with decoding facets of Revelation like the number of the beast, 666. He equated the pope with the Antichrist, as did American theologian Jonathan Edwards (1703 to 1758), who was preoccupied with connecting real-world events to events described in Revelation. And on NPR, researcher Bart Ehrman says that many folks were convinced that the French Revolution (1789 to 1794) was a critical, apocalyptic event.

On that note, Anglican clergyman John Nelson Darby (1800 to 1882) wrote in "Questions of Interest as to Prophecy" that Napoleon Bonaparte was one facet of a larger satanic entity represented by three key figures: Satan, the Antichrist, and the False Prophet, the unholy trinity. Darby was practically obsessed with eschatological studies, to the point where he founded "dispensationalism," a method of investigating history based on its relationship to Revelation's apocalypse. Queen's University says that Darby's dispensationalism was perfect for "beguiling" American evangelicals who flourished during America's turn from Calvinism during the country's 19th-century religious revolution, the Second Great Awakening (1795 to 1835).

A fully modern, 20th-century concept

It's been a long, 2000-year path to arrive at the unholy trinity by name in popular culture. The fact that such a simple topic involves such a complex history should be a perfect lesson against taking facts or ideas as self-evident. Nothing emerges from nothing.

The final piece to the unholy trinity puzzle happened during our lifetimes: The "Left Behind" book series, released from 1995 to 2007. A 16-book fictional take on the events of Revelation, its co-creator Tim LaHaye died in 2016 after selling almost 80 million copies of his very dispensationalist series. Satan is the top-level baddie in "Left Behind," followed by Nicolae Jetty Carpathia (the Antichrist) and Leonardo Fortunato (the False Prophet): the unholy trinity. The series was monstrously impactful, and nowadays the term "unholy trinity" gets tossed around for loads of stuff, including video games, black metal tours, and a Western film starring Pierce Brosnan.

Of course, there were some steps between America's Second Great Awakening and "Left Behind." In 1958, theologian J. Dwight Pentecost consolidated all manner of eschatological info into his hit book, "Things to Come: A Study in Biblical Eschatology." In 1966, theologian John Walvoord was the first person to actually coin the term "unholy trinity" in his premillennialist book, "The Revelation of Jesus Christ." And in 1970, writer and preacher Hal Lindsey popularized the term in his for-the-masses non-fiction book about Revelation, "The Late Great Planet Earth." The book was the highest-selling non-fiction book of the 1970s and sold 35 million copies by 1999.