The Untold Truth Of The Buffalo Soldiers

Most Americans know the Buffalo Soldiers. From the reggae song. You know, "Buffalo soldier, dreadlock Rasta ..." Is it stuck in your head yet? You're welcome.

What many Americans don't know is that the Buffalo Soldiers were a real thing — the name was given to regiments of black soldiers who fought for America in wars and skirmishes from 1866 to the end of World War II. Buffalo Soldiers were some of the bravest and most decorated soldiers to serve in the United States military, and yet their accomplishments aren't very well-known for the simple and awful reason that systemic racism kept those accomplishments buried, while the accomplishments of sometimes lesser white soldiers bypassed them and made it into the history books. Which is pretty much the story of black history in America, so let's just do this thing to try to make a small difference. For those who only know "Buffalo Soldiers" as a reggae song, here's the untold truth of the real-life soldiers who inspired that catchy tune.

In the beginning ...

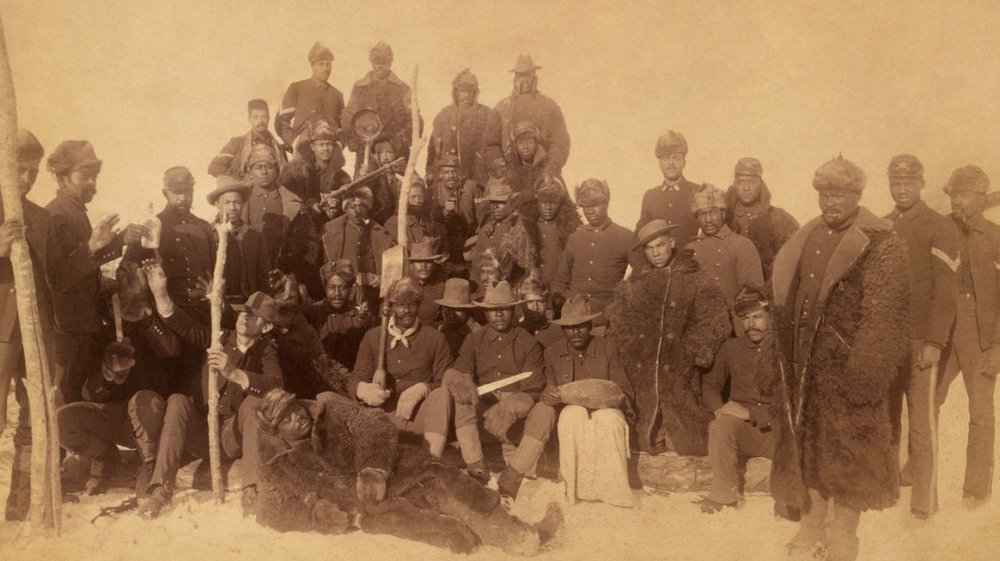

During the American Civil War, all-black regiments called the "United States Colored Troops" made up roughly 10 percent of the Union Army. Those troops were disbanded at the end of the war, and a lot of newly free blacks in other parts of the nation found themselves facing difficult circumstances.

In 1866, Congress passed the Army Organization Act, which was mostly just a lot of fluff about pay for soldiers and officers and organizational stuff. But the act also allowed for the creation of four new cavalry regiments, two of which would consist of black soldiers and white officers, and eight new companies of infantry, four of which would consist of black soldiers and white officers. Many free blacks saw this as a rare opportunity — perhaps their only opportunity — to make a decent living.

These were considered peacetime regiments, but "peacetime" isn't really a super-accurate word since there was still plenty of conflict happening in the American West, mostly against the indigenous population.

The Buffalo Soldiers were noble men doing less-than-noble work

The American Civil War freed blacks from slavery, but not from oppression. They weren't equal under the law and they faced ugly, out-in-the open racism whether they were in southern states, northern states, or the frontier. A lot of blacks saw military service as a pathway to civil rights — if they could prove themselves in uniform, surely equal rights and fair treatment would follow. Unfortunately, military service post-Civil war meant fighting for the oppression of another group: indigenous Americans.

According to History, the original purpose of the Buffalo Soldiers was to keep the natives from causing trouble. They were to help with westward expansion, which meant fighting and pushing back the native people, though that wasn't their only task. They had other responsibilities, too, like catching cattle rustlers and protecting settlers on the frontier. All nice, not-very-visible jobs, which was important because the white snowflakes living in populated communities might die from shock if they saw black men dressed in army uniforms carrying weapons.

What's in a name?

"Buffalo Soldiers" is a pretty odd name, and no one is really sure exactly why it was given to black soldiers on the frontier. According to History, the two all-black cavalry units were officially the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments, and it was the Native Americans that the men were supposed to be controlling who gave them the nickname "Buffalo Soldiers." But their reasons for choosing that particular moniker are mostly a mystery. One theory suggests that the natives thought the soldiers' thick, curly hair resembled the fur of a buffalo, but that frankly seems like an idea someone might have pulled out of their own backside. The more popular and probably correct theory is that the Buffalo Soldiers fought courageously and fiercely, so the plains people named them after the buffalo — an animal they had deep respect and reverence for.

Origins aside, it's clear that the soldiers themselves saw the nickname as one of respect, and even incorporated the image of a buffalo into their coat of arms.

Shockingly, the Buffalo Soldiers faced racism from their own government

You will of course be absolutely shocked to hear that not everyone was cool with the idea of all-black regiments and that there was a ton of racism thrown at the Buffalo Soldiers for pretty much their entire existence. According to Smithsonian, the first thing that happened was white officers (including George Armstrong Custer, remember that jerk?) refused to command them because they believed black men would run when faced with danger. Nice. Some of the officers who refused to command Buffalo Soldiers even risked losing rank, and that still wasn't enough to overcome their racism.

The all-black regiments would also get all of the worst food, the worst horses, and the crappiest equipment, and most of their accomplishments went totally unrecognized. They were often living in unsanitary conditions, and many of them died from diseases related to their living conditions and inadequate rations. Meanwhile, the white officers got everything they needed, because of course they did.

The Buffalo Soldiers were more disciplined than white regiments

Anyone who's ever watched a film about life in the army during the American Civil War knows that white soldiers were mostly louts who drank a lot and got court-martialed all the time. That's not just a figment of Hollywood's imagination, either — there's more than just an element of truth to it. According to Social History of Alcohol and Drugs, alcohol use was endemic in both the Union Army and the Confederate one — officers and soldiers drank to cope with boredom and the general awfulness of fighting in a civil war, and whiskey was given to soldiers as medicine to treat things like exhaustion and pain.

Not much really changed after the war, either. White soldiers continued to use alcohol, but the Buffalo Soldiers had much lower rates of alcohol use even though they got the worst and most dangerous assignments and faced racism from their superiors and from the citizens of the frontier towns they were assigned to protect. They had lower rates of court-martial and desertion, too, so even though life was a lot more challenging for them, they were on the whole more disciplined than their white counterparts were.

Despite all the racism, many Buffalo Soldiers received medals of honor

At first pretty much everyone was against the Buffalo Soldiers, except maybe for those far-away people in Congress who wrote them into the law in 1866. Out on the frontier, people were ruthlessly cruel. According to Smithsonian, the people who were the primary beneficiaries of their service were the most hostile of all, and sometimes black soldiers died violently at the hands of ungrateful white settlers.

That didn't deter the Buffalo Soldiers, though, who took their jobs seriously and served valiantly. During the Indian Wars, which lasted decades, 18 Buffalo Soldiers were given Medals of Honor. Keep in mind, though, that there were 426 medals given in total during those years, and black soldiers made up roughly 10 percent of the army at that time. So clearly, a lot of valiant Buffalo Soldiers were overlooked, and the ones that did receive medals had to do some pretty crazy-heroic things to get the attention of a military leadership that was otherwise prone to overlooking them. Nothing like working twice as hard to get half the recognition.

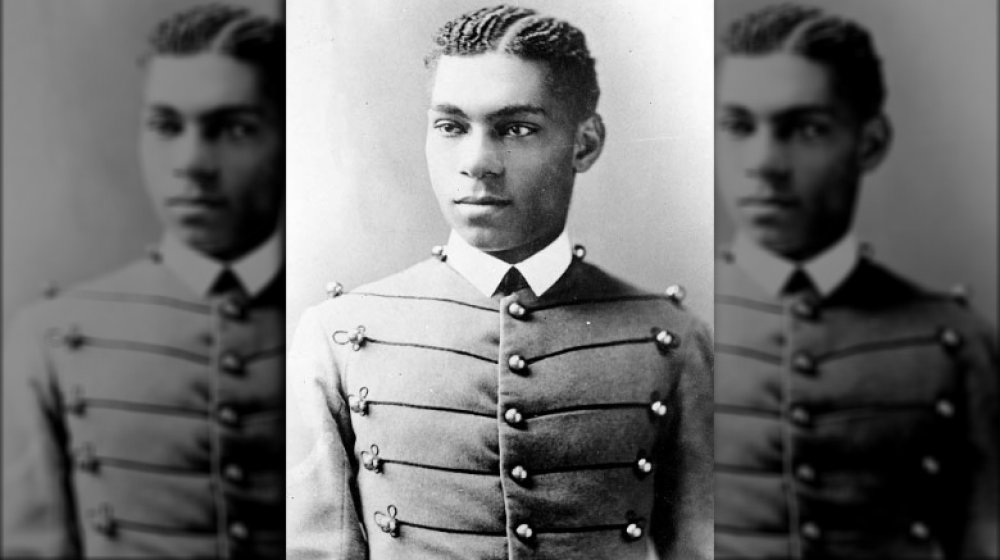

It was years before the first black graduate of West Point

A lot of blacks joined up with the Buffalo Soldiers in pursuit of civil rights and equal treatment under the law, but it was years before anyone started making real strides in the otherwise all-white military boys' club. One of the first was Henry O. Flipper, who was born into slavery in 1856. According to the National Archives, Flipper overcame enormous odds, isolation, and the near-constant harassment of classmates to become the first black graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, and the first black commissioned officer in the United States Army. Flipper graduated in 1877 and was stationed on the frontier in Oklahoma and Texas. He fought Apaches during the Indian Wars and helped build the infrastructure that made life easier for settlers.

Unfortunately, Flipper's distinguished record couldn't protect him from racism, and in 1881 his commanding officer accused him of embezzling money from commissary funds. He was cleared of the charges but the court found him guilty of "conduct unbecoming an officer" and he received a dishonorable discharge. Despite efforts to clear his name, Flipper died before the Army finally recognized its error and granted him an honorable discharge. In 1999 he was finally pardoned by then-president Bill Clinton.

Buffalo Soldiers were among America's first park rangers

No matter where they went, the Buffalo Soldiers got the crappiest, most thankless jobs going. But some jobs were less terrible than others. According to the National Parks Service, 500 Buffalo Soldiers got to do thankless work in two of the most beautiful places in the world — Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks, where they were tasked with catching timber thieves, confiscating firearms, kicking out cattle found grazing on park lands, and stopping illegal poaching. Many also served as firefighters, and were responsible for helping bring infrastructure into the parks. They built roads and trails, and constructed an arboretum in Yosemite National Park, which became the first museum ever built in a national park.

In 1903, West Point's third black graduate, Charles Young, served as acting military superintendent in Sequoia National Park. (In case you were wondering, in 1884 it wasn't any easier for African-Americans at West Point — Young later said the worst thing he could think to do to an enemy would be to make him a black man at West Point).

Young and his all-black company were sent to Sequoia to work on a stalled road project — by the end of the season Young and his men had built as much road as had been built in three previous seasons. And yet, most Americans today aren't even aware of what the all-black regiments accomplished in their beloved national parks. Three times the work, half the recognition.

Most gallant and soldierly

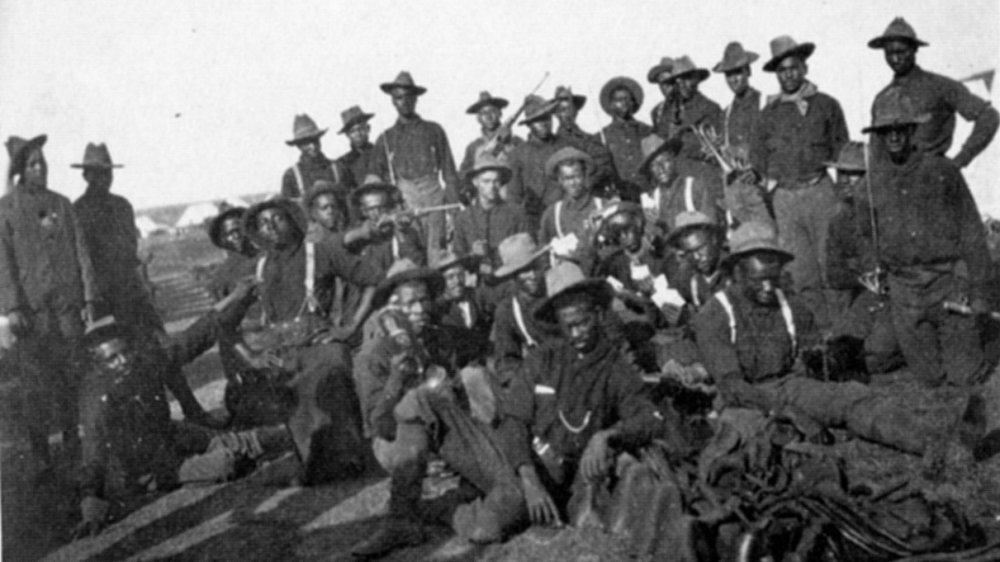

By the time the Spanish-American war broke out in 1898, blacks in America were still nursing hope that distinguished service in the military was the key to obtaining equal rights at home — even though by then the Buffalo Soldiers already had already been serving for more than 30 years and so far not much had changed. Still, when the Army shipped 17,000 men to Cuba to fight in the new conflict, 3,000 of them were Buffalo Soldiers. Back home, blacks were engaged in a fierce debate about whether black soldiers were doing any good for black civil rights — according to the National Park Service, some thought it was senseless for blacks to throw their lives away for a country that clearly did not value them as human beings. Others still believed that fighting for America was the clearest path to obtaining liberty in America.

The Spanish-American war marked the first time that black troops were stationed in the southeastern part of America, where they faced the same bigotry that their unenlisted counterparts did. When they arrived in Cuba, they faced heat, mud, and tropical diseases. Many of them served as nurses and orderlies. Four earned Medals of Honor for rescuing wounded soldiers under enemy fire. Their white comrades praised them as "most gallant and soldierly." And still, nothing really changed back home.

World War I for the Buffalo Soldiers

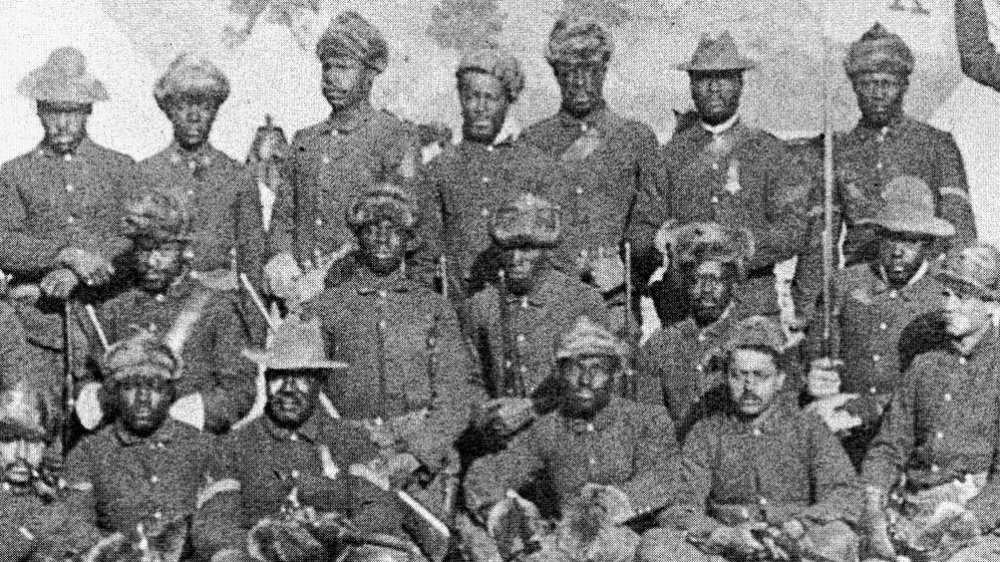

By World War I, the Buffalo Soldiers had an impressive list of honors and accomplishments and still weren't considered equal to their white counterparts. According to the National Park Service, when the United States entered the First World War, there were Buffalo Soldiers stationed in the Philippines, on the U.S.-Mexican border, and in Hawaii, and the Army just kind of left them there, because (you guessed it), they didn't think they were capable enough to send to the front lines.

But as the war grew uglier and nastier and longer, the military finally conceded to a simple fact: The war wasn't going to be won if the U.S. didn't enlist the help of everyone, regardless of color. The Buffalo Soldiers themselves remained in the United States and the Philippines, but thousands of African-Americans were eventually recruited to join the war overseas, and it's safe to say that the distinguished history of the Buffalo Soldiers helped make that possible.

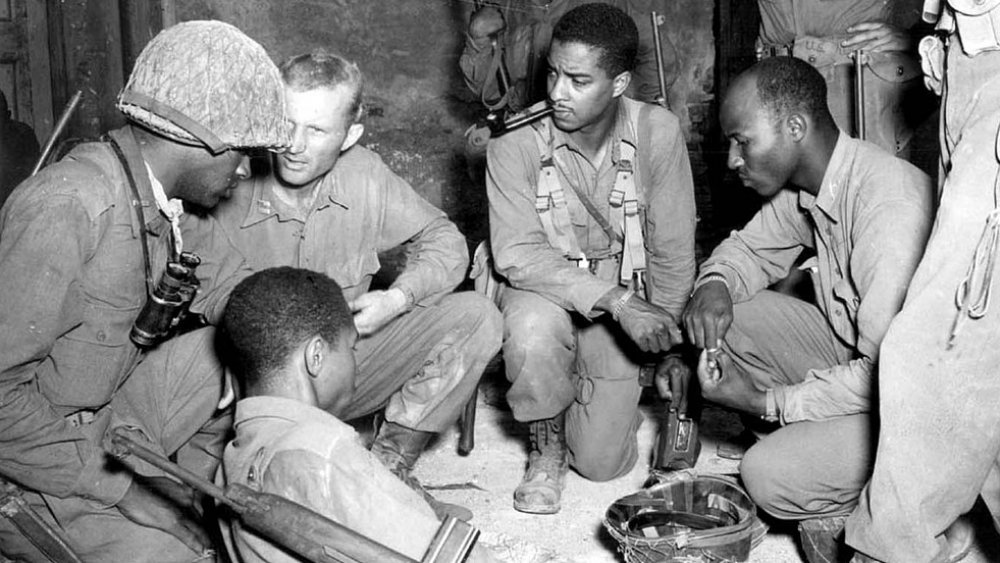

World War II for the Buffalo Soldiers

One of the two divisions that shipped to France during the First World War was nicknamed "Buffalo Soldiers," even though it wasn't part of the original regiments that bore that name. The other unit became known as "Blue Helmets." Both fought in France during WWI, and both served so valiantly that France awarded honors and medals to soldiers in each division. And still, black soldiers weren't taken seriously back home in America.

By World War II there were 909,000 enlisted blacks in the Army, but only one division saw combat. The rest of them were assigned to menial jobs like construction or graves registration, because of the enduring belief that black soldiers weren't brave enough or motivated enough for combat. The 92nd Infantry Division — the last racially segregated unit in the United States military — was the only exception. And surprise, they fought just as valiantly as all the Buffalo Soldiers who came before them.

The end of the Buffalo Soldiers

The Buffalo Soldiers had a long, proud history, but they couldn't continue to exist in a world that was finally starting to recognize the fundamental injustice of segregation. And the desegregation of the military had an unlikely champion — Harry S. Truman, who grew up with racist ideas and eventually evolved into a person who genuinely believed that all people were equal. According to the Washington Post, he had a deep change of heart upon learning of an attack on a decorated black World War II veteran named Isaac Woodard, who was beaten and blinded by a South Carolina police chief.

Truman signed Executive Order 9981 in 1948 — which desegregated the United States military — the same day he signed an executive order for the desegregation of the federal workforce. "There shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services," he said, "without regard to race, color, religion or national origin." And even so, full integration of the United States military did not happen until the Korean War, because even after that long history spanning more than a century of distinguished service, whites still refused to believe that blacks were capable soldiers.

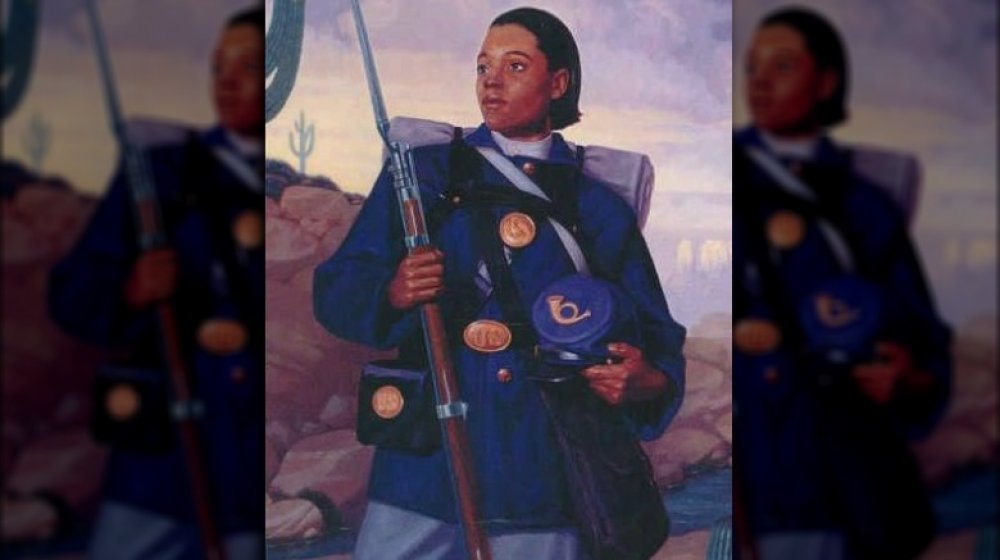

Buffalo soldiering wasn't just for men

The history of black men in the United States military is remarkable, but what about the history of black women in the military? Well for a long time that entire history was limited to just one person — Cathay Williams, the only female Buffalo Soldier.

Williams was born into slavery in 1844. According to the National Park Service, after Union soldiers captured her hometown in 1861, Williams served as an Army cook and laundress and spent time traveling with the Union Army, where she learned the routine of life on the front lines. At the end of the Civil War, savvy Williams realized that one of the best employment opportunities open to blacks was soldiering. That opportunity wasn't open to her, though, just as it wasn't open to any woman. But instead of finding work as a cook or laundress elsewhere, she traveled to St. Louis, changed her name to William Cathay and became a Buffalo Soldier.

Willams successfully passed as a man for two years. She never saw combat, but Black History Now says she was a capable soldier who learned to use a musket, went on scouting missions, and served as a guard. It wasn't until a series of illnesses that she was finally outed as a woman in 1868. Even after she'd been found out, though, her superiors had enough respect for her accomplishments that she was granted an honorable discharge.

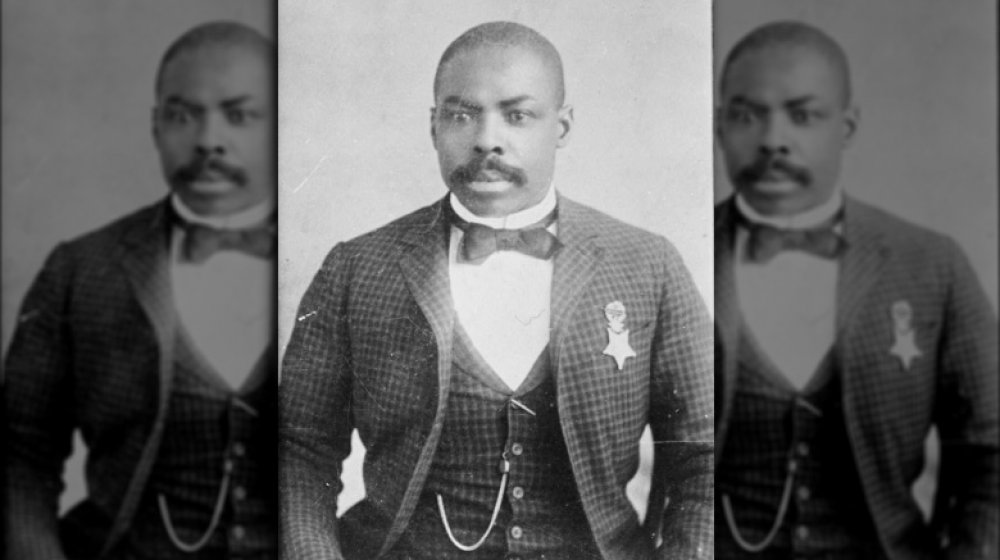

The last Buffalo Soldier died in 2005

The last Buffalo Soldier was Mark Matthews, who died at the age of 111 in 2005. According to the L.A. Times, Matthews was already an accomplished horseman when he joined the 10th Cavalry in Lexington, KY at the age of 15 (using fake documents, since 17 was the legal age for enlistment at that time). Matthews served along the U.S.-Mexican border during World War I, and in 1931 he transferred to Fort Myer, VA, where he taught horsemanship to new recruits. He remained in the Army through World War II and retired in 1949. After that he worked as a security guard, finally retiring for good in 1970 after becoming chief of the guards.

When Matthews died, he was the last surviving Buffalo Soldier and also the oldest, though at 111 he was pretty darn near close to being the oldest of just about any category he qualified for, including oldest retired security guard, oldest person in town, oldest guy who likes cheese, seriously just pick one. But even without that title, it's pretty cool that the Buffalo Soldiers made it to the 21st century, after such a long and impressive history of valor and patriotism. Thanks for your service.