5 Strange Wild West Stories That Sound Fake But Are Actually Real

The U.S. West between 1865 and 1900, the period typically considered the era of the Wild West, was full of tall tales, legends, and outright lies. And many of the false facts about the era you thought were true were created by the very characters involved. William "Buffalo Bill" Cody was a prime example of this. He had a knack for publicity and self-promotion and helped craft not only his own legend but the overarching mythology of the Wild West.

Even so, not all the strange stories from this time period are fake. Buffalo Bill did indeed scalp a Cheyenne warrior in an act of revenge for the killing of General George Armstrong Custer, who died at the Battle of Little Bighorn in Montana. James "Wild Bill" Hickok, known as a gunslinger and lawman, accidentally shot and killed a deputy. Sharpshooter Annie Oakley bested then married a fellow marksman. The trained horse Buffalo Bill gave to Lakota leader Sitting Bull performed while its owner died in a hail of bullets, and there were once camels that roamed the deserts of the Southwest. The Wild West, it seems, did indeed include some wild but true tales.

Buffalo Bill scalped a Cheyenne warrior

Beginning in 1872, William "Buffalo Bill" Cody became a popular entertainer of a mythologized West. He had been a U.S. Army scout and a prodigious buffalo hunter who slaughtered thousands of animals to feed railroad workers in the push across the country (and as part of a government tactic to eradicate the Native American population). In 1876, he left the stage and returned to being a scout.

While in Northern Nebraska, he and members of the 5th Cavalry fought a small band of Cheyenne warriors at Warbonnet Creek. Cody shot and killed the Cheyenne warrior Hay-o-wei, whose name translates to "Yellow Hair," and then scalped the man's corpse. "The first scalp for Custer," he claims he said (although none of the other soldiers who were present recall this), per Time magazine. It had only been a few weeks since the Battle of Little Bighorn, when a combined force of Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne warriors defeated and killed General George Armstrong Custer and around 200 members of the 7th Cavalry. When Buffalo Bill returned to the stage, he reenacted the scalping for rapt audiences back in the East.

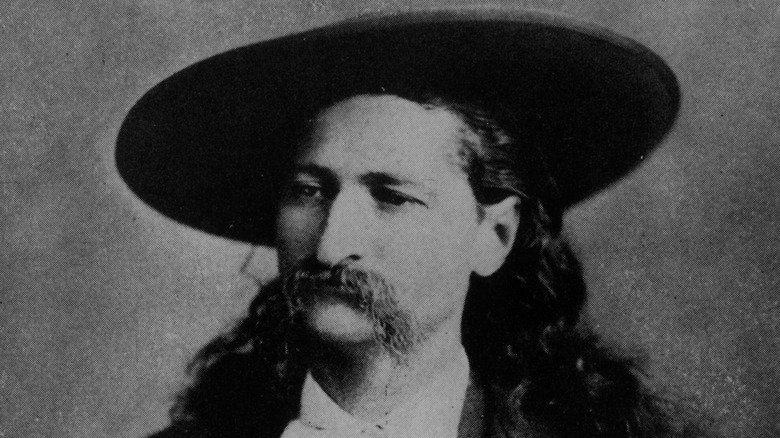

Wild 'Bill Hickok' gets fired

By the time William "Wild Bill" Hickok had become marshal of Abilene, Kansas in 1871, he'd already made a fearsome reputation for himself as a gunslinger. But on the night of October 5, his fast drawing skills were used on the wrong man. A group of rowdy Texans had arrived in town and Wild Bill, fearing trouble, confronted the 50 or so men after hearing a gunshot near a saloon. One of the Texans, a gambler named Phil Coe, drew on Hickok, missing with two shots. Hickok pulled his guns and didn't miss. But just then, a special deputy named Mike Williams, rushing to Hickok's aid after hearing the shots, came around the corner of a nearby building, and Hickok, thinking he was one of the Texans, shot and killed him. The rest of the Texans quickly left town, and Hickok lost his job as marshal.

After being fired from his job, Wild Bill joined his old friend William "Buffalo Bill" Cody on the stage, but it wasn't for Hickok, so he returned to the West. On August 1, 1876, a drifter named Jack McCall murdered Hickok by shooting him in the back of the head as he sat playing poker in Deadwood, South Dakota. After his murder, they buried Wild Bill in Deadwood.

Annie Oakley beat than married a fellow sharpshooter

Annie Oakley, born Phoebe Ann Moses in Ohio in August 1860, showed a talent for sharpshooting from a young age. Her reputation was such that when she was 15, a Cincinatti hotel owner set up a match between her and a traveling sharpshooter named Frank Butler. Butler was an Irishman who came to the U.S. at 13 and worked a variety of odd jobs before taking his marksman act on the road. The prize money was $100 (the equivalent of more than $2,800 today).

Oakley hit all 25 targets, besting Butler, who missed one. "I was a beaten man the moment she appeared, for I was taken off guard," he later said (via American Experience). Butler lost the match, but he eventually gained a wife and shooting partner. As Oakley's fame grew, he began managing her affairs, and she joined Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show in 1885. Butler and Oakley were married for around 50 years and died 18 days apart.

Sitting Bull's trained horse

The Lakota chief Sitting Bull experienced a lot in his 59 years. He was a fearless warrior, spiritual leader, and uniter of the Sioux against the white invaders who continued to encroach on their land. But he also performed in Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show in 1885 and "adopted" the sharpshooter Annie Oakley as his daughter. After four months with the show, he was "sick of the houses and noises and multitudes of men" and returned to the Dakota territory, according to "Blood Brothers: The Story of the Strange Friendship between Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill."

By December 1890, he was living on the Standing Rock reservation in South Dakota. He had become involved in the Ghost Dance movement, a Native American religion that believed in the imminent return of the buffalo and the resurgence of Native American culture. U.S. government agents, believing the movement would provoke an uprising, sent Indian police to arrest Sitting Bull. Instead, they shot and killed the chief after his followers attempted to stop the arrest. Sitting Bull's trained gray horse — a gift from Buffalo Bill — began to perform in response to hearing the gunshots. While the battle raged, the horse bowed, leapt into the air, and cantered in circles, among other tricks.

Wild camels roamed the Wild West

The Wild West and the horse are irrevocably intertwined. These animals were first introduced by Spanish explorers in the 1500s, and they were used by cowboys, soldiers, Native Americans, and settlers — for transportation as well as helping farm, haul, and hunt. But they weren't the only animals roaming the deserts at the time. In 1856, the U.S. Army brought 31 camels to Texas. A year earlier, Congress had given Jefferson Davis, the secretary of war (and later president of the Confederate States of America), $30,000 for the purchase of the animals from North Africa and the Middle East.

Davis believed they would be perfect for use in the country's westward expansion. In 1857, they sent 41 more West. But by the Civil War, all of the camels had been either sold off, slaughtered, or set free. For years afterward and into the 20th century, wild camels were seen in the deserts of Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas. Camels were just one untold truth of the Old West, and they're one of the stranger stories that sound fake but are actually true.