The Messed Up Truth Of The Gunfight At The O.K. Corral

It's a shoot-out that has come to represent the glamour and gore that defined the Wild West, or, at least, our modern-day understanding of it. Pitting a motley crew of unconventional lawmen — the Earp brothers and Doc Holliday — against the so-called Cochise County Cowboys, the gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona, was over in less than 30 seconds. When the dust cleared on the afternoon of October 26, 1881, three men lay dead. The deceased were all Cowboys: Billy Clanton and brothers Tom and Frank McLaury. Two of their compatriots fled the scene. The Earps and Holliday survived, although Morgan and Virgil Earp and Holliday were wounded.

The battle was the result of a long-standing feud between the Cowboys and the Earps with bad feeling and rivalries on all sides. This being the old west, drinking was involved. So were cards and women and out-sized egos, not to mention intense disagreement over who wielded authority in a largely lawless territory.

Countless films and TV shows and books — both fiction and nonfiction — have delved into the drama surrounding the gunfight at the O.K. Corral, insuring that it, like the Alamo, will never be forgotten. You might be surprised, though, what you don't know about this famous firefight. Read on for what really happened on that fateful day in high noon history.

Location, location, location (of the gunfight at the O.K. Corral)

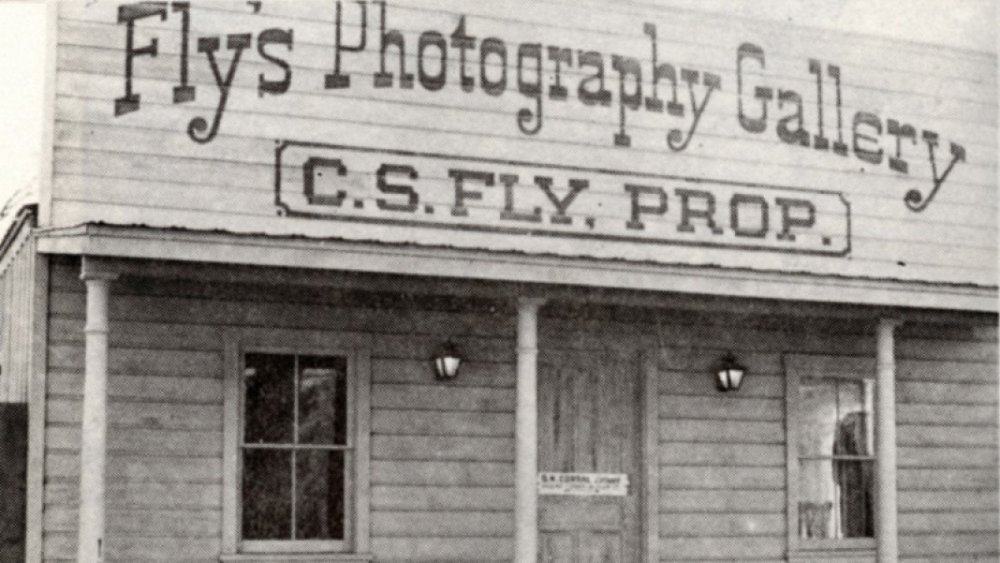

According to the Library of Congress, the "OK" in O.K. Corral stands for "Old Kindersley." The Old Kindersley Corral was a livery business that operated on Tombstone's Fremont Street from 1879 to 1888. Weirdly, the fight itself didn't take place in or next to the Corral as its name would suggest. Instead, it happened in a vacant lot next to C.S. Fly's Photographic Studio and Boarding House, six doors down from the corral. Doc Holliday, the iconic dentist-turned-tubercular gunman, was a resident of the boardinghouse. One of the fight's main instigators, Ike Clanton, took cover in the studio while shots were being fired. So did the one man who might have stopped the carnage, the sheriff of Cochise County, John Behan.

Incidentally, C.S. Fly's photographs of late nineteenth century Tombstone have become indispensable to our understanding of life in the Wild West. Fly did not, however, take any pictures of the battle or its aftermath. This Legends of America profile suggests that the Earps expressly forbid him from documenting the event. Fly did participate in one way: he disarmed the dying Billy Clanton.

Why the shootout became associated with the O.K. Corral is still a bit of a mystery, but maybe it's because "the gunfight in the vacant lot next to C.S. Fly's Photography Studio and Boarding House" doesn't quite roll off the tongue.

There were no good guys taking part in the gunfight at the O.K. Corral

The Earp brothers — Wyatt, Virgil, and Morgan — and John Henry "Doc" Holliday have long been cast as the good guys in the shoot out, whereas their opponents, the Cochise County Cowboys, have been written off riff-raff. The truth is a lot more complex than that, as this Denver Post piece makes clear. In fact, the most revered player of all, Wyatt Earp, was a fugitive from the law when he moved to Tombstone hoping to make his fortune in silver. As a young man, he stole a horse in Indian Territory. Then he escaped jail and went on the run, moving from town to town and brothel to brothel.

The McLaurys — two of the most powerful Cowboys — came from Iowa in search of cheap land on which to graze their cattle and weren't any better or worse than the thousands of other cattle rustlers who moved west in the 1870s and 80s, their eye on manifest destiny. One of the main conflicts between the Earps and the Cowboys was pretty mundane. The Cowboys were aligned with the county sheriff, John Behan. Wyatt wanted Behan's job. Also, Wyatt's brother Virgil, the acting police chief, had spearheaded a campaign to enforce restrictions on firearms. The Cowboys liked their guns.

Tensions arose as they are wont to do, but there are no villains in this tale, and no heroes, either. Just self-interested men bent on amassing power and wealth on the frontier.

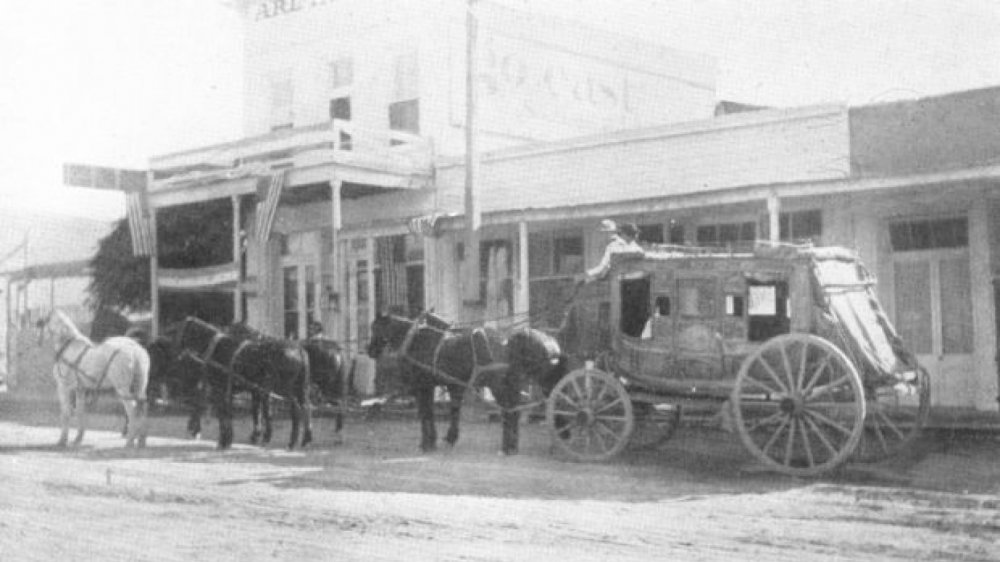

What did stagecoaches have to do with the gunfight at the O.K. Corral?

In March 1881, just seven months before the shoot-out, the Sandy Bob stagecoach was robbed by a group of masked men. According to Helldorado: Bringing the Law to Mesquite, the driver of the coach, Bud Philpot, was killed, along with one passenger. The Earps suspected the McLaury brothers were behind the robbery; the McLaurys were just as convinced it was the Earps, aided and abetted by Doc Holliday. In the meantime, as this Law Library account reveals, Virgil Earp was busy cutting a deal with Ike Clanton, one of the Cowboys. Virgil, eager to look like a tough lawman in advance of the local elections, agreed to give Ike all the reward money, no questions asked, if Clanton turned in outlaws and suspects. Clanton took the deal, but it was moot. King, Leonard, and Crane all ended up dead before Virgil could capture them.

Later, Wyatt Earp, also running for office and knowing Ike Clanton to be of a persuadable nature, approached the cowboy, suggesting they fake a stage coach robbery. He and Doc Holliday would scare away the "robbers," Earp said, and no one would get hurt. Clanton refused to take part, and bad blood continued to accumulate between the two factions. When, in early October, the Earps arrested Cowboys Frank Stilwell, Pete Spence, and Frank Stilwell for robbing a stagecoach out of Bisbee, the Cowboys vowed revenge. They didn't have to wait long.

The past is female

The O.K. Corral gunmen were obviously colorful characters, but the women with whom they kept company were just as noteworthy. Take, for instance, "Big Nose" Kate Horony, the daughter of a Hungarian doctor. According to Vintage News, Horony, orphaned and working as a prostitute at Texas' Fort Griffin, met and fell head over heels for Doc Holliday in 1875. Later, when Holliday was arrested for killing a bully during a card game, Horony set the jail on fire as a distraction and sprang her man.

Wyatt Earp's women were likewise fascinating. As this AZ Central feature explains, Wyatt moved to Tombstone with Mattie Blalock, a Dodge City prostitute. Blalock was addicted to laudanum, i.e. liquid heroin for fancy ladies. (She would later die of an overdose.) Enter Josephine "Sadie" Marcus, a former actress and, at the time, the companion of the county sheriff, Johnny Behan. Marcus eventually left said sheriff for Earp, unbeknownst to Blalock, whom Earp had sent to California to wait out the violence brewing in Tombstone. Marcus and Earp remained together the rest of their lives, and it's because of Marcus that Earp is thought of as the hero he is today.

And there's Louisa Houston Earp, Morgan Earp's beautiful and articulate wife who was a granddaughter of Sam Houston, and Allie Earp, wife to Virgil, who never left her husband's side and lived to be 98. Flinty women, all, and unsung heroines of a rough and tumble era.

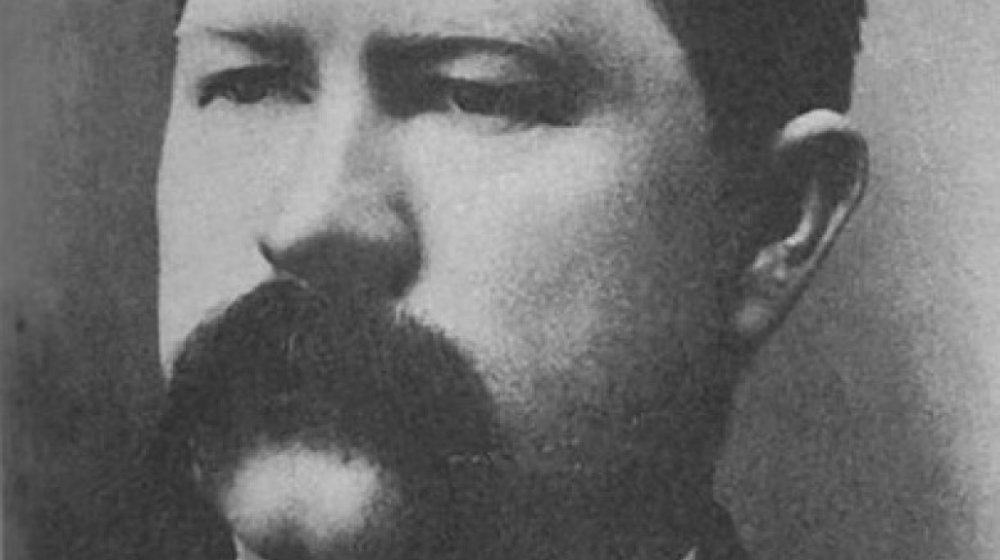

The real hero of the gunfight at the O.K. Corral wasn't Wyatt

In films and other retellings of the shoot-out, it's Wyatt Earp who usually gets all the glory — thanks in large part to the public relations campaign waged by his longtime companion, Josephine "Sadie" Marcus – but according to most scholars and this article in We Are the Mighty, the real stand-up guy in this Wild West drama was Virgil Earp. Earp served as an infantryman in the Union Army in the Civil War before heading west to join his younger brothers, Wyatt and Morgan. (He apparently moved west to nurse a broken heart — the woman he loved married someone else during the war.)

Virgil quickly made a reputation for himself as an effective, no-nonsense lawman, earning badges in both Prescott, Arizona and Tombstone. His goal in Tombstone was to put a halt to a rash of stagecoach robberies that were terrorizing the populace, and his skills as a sharpshooter went a long way toward helping him accomplish his goal. And he outlawed carrying deadly weapons within the city limits of Tombstone. That crusade put Virgil in direct conflict with the Cochise County Cowboys, who felt unfairly targeted by the Earps and their posse.

On that fateful day in October 1881 when a bloodbath seemed inevitable, Virgil attempted to get to the Cowboys to drop their weapons. They didn't, of course, and a firefight ensued, with Virgil continuing to unload his gun even as he took a bullet to the leg.

When smoke gets in your eyes during the gunfight at the O.K. Corral

No one knows for sure what guns were actually used in the gunfight at the O.K. Corral, although, according to this piece in History and Headlines, it's almost certain that they were all black powder weapons, the smoke of which would have added to the confusion of an already chaotic scene. Over the years, a number of antique gun dealers have profited handsomely from the sale of guns supposedly deployed at the O.K. Corral — one Colt .45 single action revolver rumored to have belonged to Wyatt Earp sold at auction for $225,000, and a shotgun reportedly used by Holliday went for $150,000 — but, as this USA Today article shows, the authenticity of those weapons is still up for debate.

Lawmen at the time — Virgil Earp was Tombstone town marshal, and he'd recently deputized his brothers, Wyatt and Morgan, as well as Doc Holliday — often carried single action revolvers. Holliday supposedly used a 10-gauge, double-barreled shotgun given to him by Virgil.

The Cowboys all claimed to have been unarmed at the time of the shootout, but with the exceptions of Ike Clanton and Billy Claiborne, who fled the scene, that obviously turned out to be untrue. Frank McLaury and Billy Clanton were found dead at the scene with Colt Frontier revolvers in their hands. Tom McLaury was almost certainly a victim of Holliday's gun. His body was riddled with at least 12 buckshot wounds. So much for Virgil's gun control crusade.

The Cowboys in the gunfight at the O.K. Corral weren't all that

As enemies of the Earps, the Cochise County Cowboys (three of whom perished in the shoot-out) have sometimes been portrayed as evil men bent on killing, but for the most part, they were considered by the locals to be more of a nuisance than a group of real villains.

According to this look at the Cowboys' history, the posse boasted up to 300 members in its heyday. Led by the McLaury brothers — Tom and Frank — as well as notorious tough Johnny Ringo, and Ike and Billy Clanton, the Cowboys specialized in cattle rustling and small-time heists. They rode through towns in the Arizona territory, brandishing their pistols and putting the fear of God into women, children, and preachers, and they became sworn enemies of the Earps, who wanted to bring the so-called Cowboys to heel.

A number of petty incidents of horse theft and retribution between the Earps and the Cowboys took place between 1879 and the shoot-out in 1881, the bulk of which put the McLaurys and Clantons and other Cowboys in a bad light. An LA Times piece on the Clanton clan suggests, though, that Hollywood and even historians have gotten it wrong all these years. Ike Clanton, for instance, the most demonized figure in the story, ran a lunch counter. And Tom McLaury was unarmed at the time of the shoot-out. Maybe the Cowboys weren't so dastardly after all.

I like Ike (Clanton)

Most versions of the O.K. Corral story put the blame for the gun fight squarely on the shoulders of cowboy Ike Clanton who, Wild West lore suggests, repeatedly threatened to kill the Earps for getting in his cattle rustling way.

In the days leading up to the shoot-out, the Cowboys (namely Clanton), the Earps, and Doc Holliday were all quite busy drinking and trading barbs and threats, and Clanton was overheard in more than one Tombstone saloon telling patrons that he planned to shoot the Earps on sight as soon as he could get his hands on a weapon. But Clanton was known for talking a big game, and, according to his surviving relatives, the Earps and Doc Holliday were the real instigators, robbing stagecoaches and getting away with it and pistol whipping and harassing the Clantons and McLaurys whenever they got a chance.

The truth most likely lies somewhere in between. What we know is that, after an evening of drinking and bragging, the Earps and Holliday faced off against the Clanton and his Cowboys in a historic firefight that killed Ike Clanton's brother, Billy, and stained Ike's reputation forever. He is now often described as a coward and a blowhard because, having boasted about his gunslinging prowess, he fled the scene of battle, later bringing charges of murder against the Earps and Doc Holliday. All four men, incidentally, were acquitted, and Ike Clanton was killed by police in 1887.

Tombstone grieved the Cowboys

Wyatt Earp described the Cochise County Cowboys as "low lifes and cow thieves." Regardless, the town mourned Billy Clanton and Tom and Frank McLaury in spectacular style, with 2,300 people paying their respects over the course of the day-long memorial.

According to this archived piece from the Tombstone Nugget, the funeral procession wound for two blocks and was comprised of three hundred people on foot, 22 carriages, and several men on horseback. A brass band led the way to the cemetery.

And the cemetery where the men were buried, Boothill, is so-called because the people interred there often died with their boots still on. As HistoryNet points out, a number of Wild West towns had their own "boot hills," makeshift graveyards where the dead were buried without much ceremony. Tombstone took it an, ahem, step further and christened their cemetery Boothill. A number of famous outlaws and legends are buried there, including "Old Man" Clanton, the head of the Clanton clan, and Margarita, a dark-eyed, sultry prostitute, stabbed to death by "Gold Dollar," her pretty blonde rival.

Vigilante justice

Some tales of the Wild West are greatly exaggerated in their wildness, but in the months leading up to the gunfight at the O.K. Corral, as well as in the months following, no one — no one — was charged with a crime. Masked men robbed stagecoaches and got away with it. Or, in the case of the outlaws suspected of the Sandy Bob stagecoach robbery, they were killed before they could stand trial.

According to this detailed look at the events that precipitated and followed the shootout, men simply took justice into their own hands, meaning that, after the Earps and Doc Holliday were exonerated for the killings of Billy Clanton and the McLaury brothers, Morgan Earp ended up dead, shot to death in a saloon, and Wyatt, vowing vengeance for Morgan, assembled a posse and unleashed a vendetta, gunning down Frank Stilwell — the man he suspected of killing Morgan — not to mention Stilwell's accomplices, Florentino Cruz and Curly Bill Brocius, in cold blood.

We report, we decide what happened in the gunfight at the O.K. Corral

Newspaper accounts of the gun battle varied greatly, depending on the individual publication's alliances with the fighters. The Tombstone Epitaph sided with the Earps and the Nugget was with the Cowboys.

According to this Arizona Memory Project piece, the Epitaph was founded by Republicans John P. Clum, Thomas Sorin, and Charles Reppy. The newspaper's name had many joking that it would be dead within a year, but the Epitaph proved to be resilient and relevant, partially because of Clum's mission to use its pages to rid Tombstone of corruption, not to mention those pesky Cochise Cowboys. Clum wasn't entirely pure in his motives. The Epitaph, in addition to aligning itself with the Earps, was also in the pocket of mining interests in the town.

The Nugget, in contrast, was a Democratic paper that championed the Cowboys and was, in its coverage of the gunfight, unabashedly biased against Holliday and the Earps. In this article about the battle's aftermath, the writer strains credulity, claiming that the Clanton boys, known for stealing cattle and indiscriminately waving their weapons around, "generally conducted themselves in a quiet and orderly manner when in Tombstone."

Tombstone primed for battle

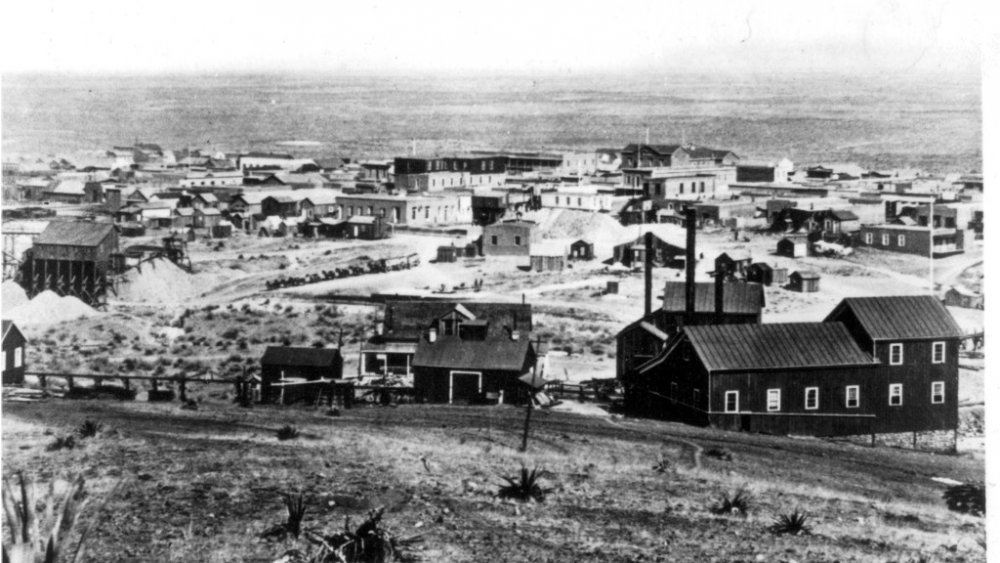

At the time of the fight, Tombstone, Arizona was a powder keg of warring factions and tensions about to explode. It was also a den of iniquity. According to Smithsonian Magazine, it had, in the late 1870s and early 1880s, two dance halls, a dozen gambling parlors, twenty saloons, and, in the words of one resident, "two Bibles."

Tombstone began as a single silver mine. Prospector Ed Schieffelin left an Arizona Army post in 1877, hoping to strike it rich in the Dragoon Mountains. His friends warned him, that, thanks to the large Apache presence in the area, he was, in effect, digging his own grave. He proved them wrong, though, and discovered a rich silver vein he named "Tombstone." A town sprung up around his good fortune, and by 1880, the place was teeming with horses and stage coaches, with countless other prospectors and prostitutes and aspiring politicians.

Saloons and brothels did very good business. So did miners. People continued to pull riches from the ground for seven straight years when, according to WildWest.org, a rising water table put an end to operations. Tombstone survived plenty of booms and busts, and it eventually earned the name "The Town Too Tough To Die," because it rode out the Great Depression in typical stiff upper lip style.