Why A WWI Time Capsule In Missouri Required A Bomb Squad When It Was Opened

So we all know the idea behind a time capsule, right? You take a bunch of junk, stuff it in a box or whatever, maybe bury it in the backyard. And then after you're dead, someone finds your cursed and shrunken lemur head and takes it to a shamanic witch doctor in New Orleans to ritually cleanse you of the demonic entity that's attached itself to you and your family and ... Okay, fine. Maybe there's no curse. But there's definitely something spooky about opening a container that acts like a musty vault to another age. Also, something might explode.

This is exactly what happened at the World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri (minus the curse). On October 16, 2024, museum staff opened a World War I-era time capsule very, very gingerly. The Kansas City bomb squad stood by ready to intervene. Why? There was film inside.

As the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia reported, old film likely contains cellulose nitrate, a man-made polymer developed as far back as 1850 and first marketed by Kodak — yes, the camera company — in 1889 as a photographic film base. Folks shot on cellulose nitrate-based film all the way to 1950, when it got phased out. The only problem? Such film gets highly flammable as it deteriorates over time. There was a possibility that the contents of the WWI time capsule might go boom when exposed to air.

Nitrate film is now stored safely

At this point, You might be wondering: "So, if filmmakers shot on nitrate-based film for over 60 years, does that mean that there's explosive film hanging around everywhere in vaults, basements, closets, and such?" Shh, maybe if we don't think about it it won't all go up in flames and bring down buildings and human lives with it.

Okay, the situation isn't that dire — at least not since 1934 or so. During the presidency of Calvin Coolidge, the U.S. Congress passed the National Archives Act. The legislation finalized the creation of the National Archives and Records Administration agency, which included a physical building with a section dedicated to storing video and audio recordings. By 1936, tests were underway to safely store nitrate-based film that could explode on contact with oxygen as it deteriorates. They proved successful, as 1,000 feet of old film blew up inside a container that held the detonation, the 1,500-degree Fahrenheit heat, and did nothing more than seeth a little smoke.

It's good that we can safely store nitrate-based film, too, because all it would take is one ignited reel to cause a chain reaction if grouped together with others. Such fires flare up instantly, burn bright and hot, and for all practical purposes can't be extinguished. Also, such film sometimes comes equipped with its own accelerant — camphor, an extremely flammable chemical.

A delicate time capsule extraction

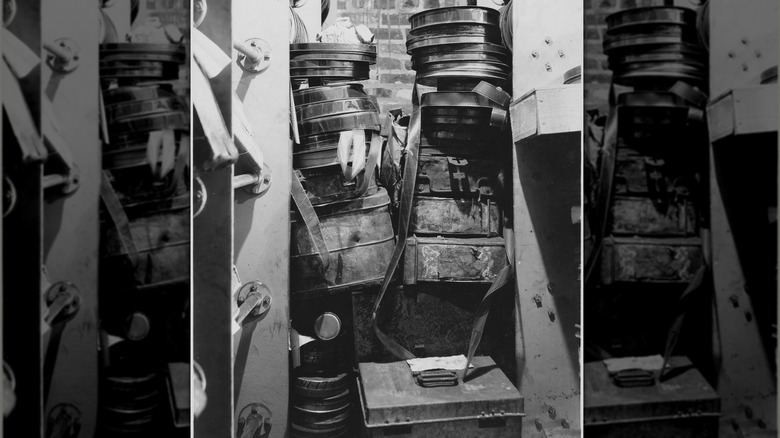

The potentially lethal, film-containing time capsule in question came from the Liberty Memorial Tower at the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri. The case was entombed in the structure 100 years prior following the end of World War I and set to be extracted in October 2024. Museum staff had to drill 1.5 feet into a wall made from concrete and limestone before they even attempted to open it. "It was not easy," ABC News quotes chief curator Christopher Warren. "There was no door to open and pull the time capsule out."

While we're not sure if the Kansas City bomb squad had a hand in physically opening the capsule, they were on hand in case it blew up in anyone's face. Thankfully, this didn't happen, and the contents inside remained safe. "Nothing caught on fire, which was great for preservation," Warren said. "Maybe not as interesting as it would have been if things would have exploded." Also, there were children in attendance, so we can be sure that all precautions were taken before the capsule was opened.

The time capsule's preserved contents — 15 objects total — included seeds, newspapers, a copy of the Bible, and a letter written by President Calvin Coolidge himself. Interestingly enough, the container also contained a note about General John J. Pershing, the leader of the U.S.' armed forces during World War I. He was apparently unable to make the original 1924 sealing of the time capsule.