What Pre-American Puerto Rico Was Really Like

Today, Puerto Rico is a paradise of palm trees, tropical fish, and relaxation. Oh, it also has 43.5 percent poverty, toxic drinking water, and a crippling debt of around $123 billion. In other words, Puerto Rico has come a long way since Christopher Columbus' arrival in 1493. We can debate about whether or not it went in an especially productive direction, but the truth is that the Puerto Rico of today barely resembles the one that existed 600 years ago.

So what was life like in Puerto Rico before the Americans showed up? Well, there were the good times ... and then the Spanish eventually showed up, with their guns, greed, and bad attitudes. Sure, Puerto Rico looks like a tropical paradise, but its history is full of violence, pirates, and even some undead creatures (sort of). From life before Columbus to the early arrival of US soldiers, here's what life was like in pre-American Puerto Rico.

Surprise, there were already people living there when Columbus arrived

Christopher Columbus reached Puerto Rico in 1493, during his second voyage to the "new world." He didn't find a land of palm trees and snorkeling outfits, because there were no snorkeling outfits in 1493, and also, there were no palm trees. What he did find were the indigenous Taíno people, who were all, "Who the heck is this white dude, and should we be feeling a sense of ominous foreboding right now?"

The Taíno called the island Borikén, which means "the land of the brave lord." Columbus called it "San Juan Bautista" in honor St. John the Baptist, because who cares what the natives called it. According to the Yale Genocide Studies Program (and just based on the source, you already know where this is going), in 1508, there were roughly 30,000 people living on the island of Puerto Rico, which is when the poop really started to hit those weird leaf-shaped ceiling fans that always seem to be in tropical resorts. The Taíno either didn't get that ominous sense of foreboding, or they just ignored it, because they greeted Columbus warmly, and then showed him the gold nuggets in the nearby river. Oops. So what's the moral of the story? Don't tell the Europeans about the gold.

Life before Columbus

Before Christopher Columbus got there, the Taíno lived the sort of life most of us would envy. According to Lonely Planet, a 1505 account of the Taíno described them as living in cities with "wide, straight roads" and "artfully made" homes with walls of woven cane. They slept in hammocks, and they were skilled craftsmen who carved wood and made pottery and baskets. They ate tropical fruit, farmed cassava and other indigenous crops, and supplemented their diet with what they could hunt or pull out of the sea. In their off-time, they played a game that resembled modern soccer, with a rubber ball and teams of up to 30 players.

The Taíno believed in one god, and evidently, they were also Walking Dead fans, so yeah, these people were cool. In the Taíno tradition, the dead could come back at night and walk around in the villages and forests, eating tropical fruit and seducing unsuspecting men (though only the undead women could do that). You could tell if someone was alive or dead by touching them on the stomach. In the Taíno tradition, the walking dead didn't have navels.

According to Smithsonian, the Taíno who met Columbus didn't have weapons, although they weren't totally innocent as far as potential conflict was concerned. (About 100 years prior to Spanish occupation, they'd been attacked by a rival tribe from South America). "They do not carry arms or know them," Columbus wrote. "They should be good servants." So yeah, that wasn't great news for the Taíno.

Ponce de Leon shows up in Puerto Rico

Columbus named the town where he landed "Puerto Rico," which means "rich port." At some point, the name of the town and the name of the island got switched around, but as long as the word "rich" was in there somewhere, who cares. The Spanish heard about the gold soon enough, and what's really surprising is that it took them more than six and a half minutes to move in and start tearing everything on the island into pieces.

According to the Yale Genocide Studies Program, in 1508, Ponce de León got assigned to explore the island of Puerto Rico, and also to subjugate the people of Puerto Rico because that just goes with the conquistador territory. The Taíno greeted Ponce de León with the same kindness and generosity they'd greeted Christopher Columbus, and Ponce de León was all, "Cool, now please be my slaves." By 1509, Ponce de León controlled most of the island, and the formerly peaceful Taíno, who were used to fishing and farming, suddenly found themselves working in the gold mines as forced laborers.

The town where the gods came to die

At first, the indigenous people weren't sure what to make of the Spanish. They were weird, kind of pasty, and also possibly immortal. The Taíno didn't know for sure, because the Spanish weren't exactly forthcoming with the truth about whether or not they were just regular people or some kind of supernatural race of god-beings. So for the first few years of Spanish occupation, the Taíno kind of lived in a state of uncertainty about if they should just be submissive to the potentially supernatural Spanish or kick their butts all the way back to Europe.

According to the Puerto Rico Herald, there's a town on the western side of Puerto Rico's Central Mountain Range that's locally known as "the town where the gods came to die," because that's where the Taíno established once and for all that the Spanish were not, in fact, gods. How did they do that? Well, according to local legend, they cornered some Spanish dude and then drowned him, and then they watched his body decompose for three days, just to be sure. That was when the Taíno decided they didn't have to take this crap anymore, and the 1511 rebellion was born.

The Taíno even had a couple of decent successes. Raids on Spanish settlements went well for the natives, but then Ponce de León heard about the uprising and unleashed an army of 100 well-armed Spaniards, who killed around 11,000 Taíno.

The conquistadors forgot to bring Spanish women with them

So the Spanish showed up, settled in, and then they were all, "Hey, wait a second, something's missing." As it turned out, they'd forgotten to bring women. Yes, the Spaniards may have gotten their gold, but they weren't getting something else that tends to be rather important to manly conquering types.

According to the Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology, the Spanish crown officially encouraged the colonists to marry Taíno women starting in 1501. In fact the practice was so common that by 1514, a survey showed that roughly 40 percent of the Spanish men living in Puerto Rico had Taíno wives, although Smithsonian says the real number was likely even higher than that.

The children of Spanish/Taíno unions (called "mestizos") often went on to marry people of African descent, so today's Puerto Ricans have a rich background that includes genetic influences from three continents. That's not quite the same thing as preserving culture and heritage and, you know, not committing genocide against the Taíno people, but at least some part of those lost people still lives on.

The Taino were pretty much driven to extinction in a single generation

Not everyone thought that it was okay to enslave the Taíno. According to the Yale Genocide Studies Program, in 1511, Fray Antonio de Montesinos argued against the way the natives were being treated, but by then, it was already pretty much too late. The Taíno were dying in huge numbers from poor living conditions and from European diseases like measles, influenza, and smallpox. Because they'd been taken out of the fields to work in the mines, there was no one left to grow food, so many of them were starving. Some committed suicide in order to avoid slavery and subjugation. By 1515, there were only 4,000 left. About 30 years after that, a Spanish bishop estimated there were only 60 Taíno left.

What's left of the Taíno today? Some of their vocabulary, for a start — "barbecue," "hammock," "canoe," and "manatee" are all Taíno words. Some of their traditions persist, too. There are communities that still use Taíno methods of agriculture, fishing, and medicine. And their genes are still in the population of people now living in Puerto Rico. That's really it, though. The Taíno will never really be more than a faint, ghostly presence on the island they once called home.

Wait, no coconuts in pre-American Puerto Rico?

Today, Puerto Rico is kind of synonymous with palm trees. It's hard to imagine those sandy shores and tropical waters without a few palm trees blowing in the wind. So here's the most shocking thing you'll read all day: Coconuts in Puerto Rico are an invasive species.

Yes, it's true, when Columbus first reached Puerto Rico, there were no palm trees, and there were no coconuts. There were palm trees on some parts of the Pacific American coast, but the species is actually indigenous to the Asian tropics, and it hadn't yet spread as far as Puerto Rico. According to The Caribbean: A History of the Region and its Peoples, coconuts reached the Caribbean around 1525, and they weren't the only non-indigenous species to be introduced to the islands at that time.

Before European occupation, bats were the only mammals endemic to Puerto Rico. Then the colonists imported cattle and pigs. They brought dogs, too, some of which ran off and turned feral. They also introduced mongoose to help control the rodents (that they also introduced). There are now four species of monkey living in Puerto Rico, too. Those escaped from a medical research lab.

Gradually, more and more non-native plants were introduced to the island, including oranges, coffee, mangoes, sugarcane, and bananas. And naturally, the colonists had to get rid of native habitat to make room for all that agriculture. And so the landscape today is really nothing like it was in pre-American Puerto Rico.

Pirates and privateers loved Puerto Rico

They weren't called the "pirates of the Caribbean" for nothing. Puerto Rico was a prime target for Captain Jack Sparrow and other roving bands of swashbucklers (actually Captain Jack is fictional, but we like to imagine). That's partly because it was in very close proximity to the otherwise unoccupied Virgin Islands, which was the perfect place for pirates to hide. Pirates and privateers (who were basically pirates working in an official capacity for some government or another) were constantly launching attacks against San Juan.

In the early years of Spanish settlement, the pirates were targeting cargo ships transporting gold off of the island en route to Europe. Later, attacks happened because other nations coveted that strategic location between North, Central, and South America. According to ThoughtCo, the French attacked Puerto Rico in 1528 and razed several settlements, and then in 1595, it was Sir Francis Drake, though the Spanish were able to defeat him. In 1598, a band of English privateers led by George Clifford, the English earl of Cumberland, attacked and captured the whole island, but in the end, Clifford's men succumbed to local illnesses and the fact that no one there actually liked them, so their occupation only lasted a few months.

Puerto Rico had a huge black market

The Spanish crown didn't trust anyone, least of all a colony they couldn't see or easily communicate with. So anything exported from Puerto Rico had to pass through Spain, and anything imported to Puerto Rico also had to pass through Spain. That really means that the island was prohibited from trading with its closest neighbors. Officially, anyway.

The reality was that, of course, Puerto Rico was going to trade with its neighbors, and since that trade was basically illegal anyway, there was really nothing stopping them from building a profitable and enormous black market on the island. Merchants made a tidy living selling stuff to their neighbors on other Caribbean islands, mostly sugar, ginger, and slaves. Some historians think that pretty much everyone on the island, from priests to soldiers to the people at the top, were actively engaged in smuggling and black market trade. Smugglers were generally punished if caught, with "if" being the operative word. Puerto Rico didn't have much oversight from far-away Spain, so many cities and citizens became wealthy from illegal trade activity. In fact, a lot of the opulent homes and fountains that attract tourists today were built on money earned from black market trading.

The Spanish sunk more money into forts than housing

Obviously, if you're going to get attacked by pirates all the time, you're going to need to build fortifications so you can protect yourself and your possessions. According to the Yale-New Haven Teacher's Institute, Spain invested in massive forts to help protect the island from attackers, but meanwhile, they neglected to build things like public buildings, churches, and you know, places for people to live.

By the 1530s, the Spanish were already at work on Castillo de San Felipe del Morro, Puerto Rico's most famous fortification. A cannonball fired from the fort was responsible for the retreat of Sir Francis Drake, but it wasn't enough. After "El Morro" (as it was known) fell to George Clifford in 1598, the Spanish were convinced that they needed to wall in the entire city. By 1639, the 400 plus homes and 3,600 citizens of San Juan were safely tucked away inside a giant fortress made from limestone, mortar and sand. To their credit, El Morro never fell again. Today, Puerto Rico's forts are the oldest European-style fortifications within the US and its territories.

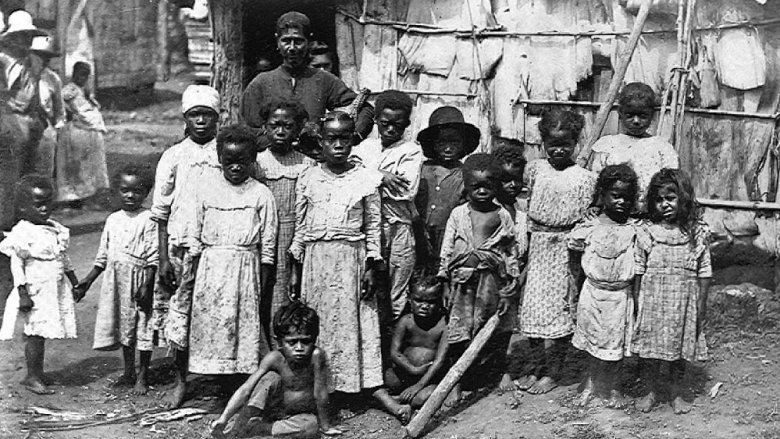

Africans were enslaved in Puerto Rico, too

After the Taíno died out, the Spanish were all, "Wow, what an awful thing we did to the Taíno. Let's talk about why this happened and make sure it never happens again." Okay, no they didn't. Mostly they were all, "Who are we going to get to work in the gold mines now?" So they started importing African slaves to the island.

Africans worked in the gold mines and in the fields. According to Face 2 Face Africa, Puerto Rican slaves were educated by their Spanish "owners," and they sometimes got to grow vegetables on small plots of land. But other than that, being an African slave in Puerto Rico was exactly as sucky as it was anywhere else in the world. Slaves were branded on their foreheads so they couldn't escape or be stolen. By 1789, the Spanish crown declared that slaves could earn or buy their freedom, but it was an empty promise since that was around the time that the Spanish were expanding their sugarcane plantations. Sugarcane is a labor-intensive crop, which means the Spanish needed more slaves, not fewer. It wasn't until March 1873 — almost a decade after the end of the American Civil War — that slavery in Puerto Rico was finally outlawed.

There were also free blacks in Puerto Rico

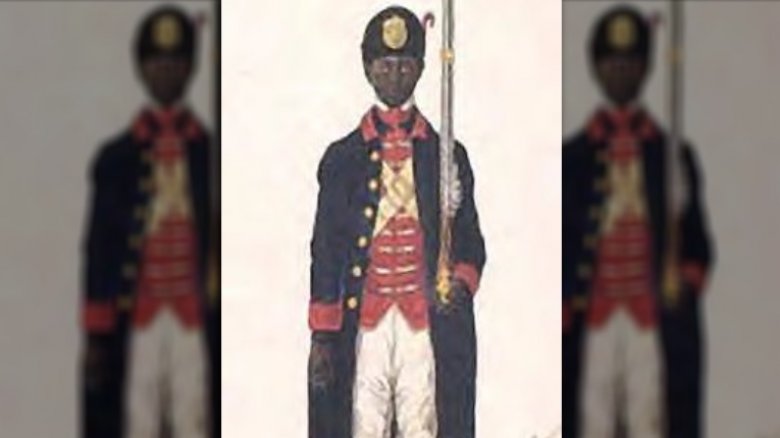

The first African to arrive in Puerto Rico was Juan Garrido, a free man who was also a conquistador. He traveled to Puerto Rico with Ponce de León and spent 13 years doing the same awful stuff as all the rest of the conquistadors.

Garrido wasn't the only free African to come to Puerto Rico. By 1570, most of the island's gold had been dug up and sold. The gold-loving Spanish gradually began to give up on the island, and many of them were leaving to seek their fortunes in the wealthier colonies. Puerto Rico was still in a strategic location, though, and the Spanish were a little concerned about what the dwindling population might mean for their continued ability to hang onto the island. According to Minority Rights, without the Taíno and the dwindling population of Spanish colonists, the island was a ghost of its former self, and the Spanish knew they needed to attract new colonists if they were going to continue to hold Puerto Rico and man the garrison.

In 1664, the Spanish issued an official edict, offering freedom and land to Africans living in non-Spanish colonies like Jamaica. A lot of families took them up on the offer, moving into the western and southern parts of Puerto Rico and joining the militia.

Out of oppression and into more oppression

In the end, Spain made all the same stupid mistakes most colonizers make. They exploited the indigenous people, they messed up the land, and they planted coconuts. Okay, the coconuts weren't terrible, but for the most part, colonists don't usually leave things better than they found them. By the end of the 19th century, Puerto Rico had a lot of working class poor, and most of them had had enough of the Spanish. So when the US invaded Puerto Rico in 1898 with promises of freeing them from oppression, Puerto Ricans were all, "Cool."

The invasion was a part of America's Spanish-American war strategy. Puerto Rico was a Spanish territory, but it also had a lot of sugar plantations, and you know how Americans feel about sugar. But History says after America won the war, it didn't exactly keep any of those "freeing them from oppression" promises, and basically told Puerto Rico that their democratically elected government meant nothing because they were an American colony now.

So why didn't Puerto Rico ever achieve statehood? Well, in 1901, a number of legal opinions called the "Insular Cases" dismissed the people of Puerto Rico as "alien races," and argued that they could never learn the "Anglo-Saxon" ways, and would therefore never be good enough for statehood. Hey, guys, thanks for the freedom from oppression.