What Life Was Really Like In British India

There are few things we can all mostly agree on, and one of those things is colonialism. Colonialism was bad, and we all know it, with the possible exception of like 59 percent of the population of Britain, but never mind. Most people who take the time to look at the history of colonialism and its impact on the countries and cultures where it was practiced will arrive at the same ugly conclusion: With a few minor exceptions, people suffered under British rule. They were starved, stolen from, denied justice ... but hey, they did learn how to appreciate shepherd's pie and toad in the hole, so, perks.

India was ruled by the British for 200 years — first by the private East India Company, and then by the British government after the East India Company was finally abolished. So if you want a textbook example of the great experiment of colonialism, well, here's what life was really like in colonial British India.

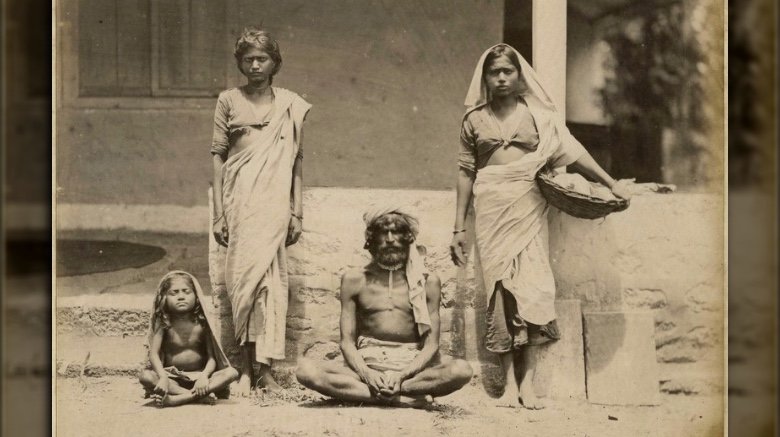

Poverty in India skyrocketed under the British

Poverty existed in India before the British, thanks in part to constant war, food shortages, and the caste system, but in general Indian society took care of everyone. According to Indian Congress leader Shashi Tharoor, India was once one of the wealthiest countries in the world — and then the British showed up. "The British came to one of the richest countries in the world," he said during the launch of his book, An Era of Darkness: The British Empire in India, "a country which had 23 percent of global GDP ... a country where poverty was unknown." While that last bit is an exaggeration, the British certainly took poverty from small problem to national crisis.

The British didn't implement any policy or introduce any technology with the express purpose of helping Indians — everything they did was for the sake of enriching the British, and that meant two centuries of exploitation and looting, both the metaphorical kind and the actual kind. "This country was reduced to one of the poorest countries in the world by the time the British left in 1947," Tharoor said. So in conclusion, colonialism stank for nearly everyone except the British. End.

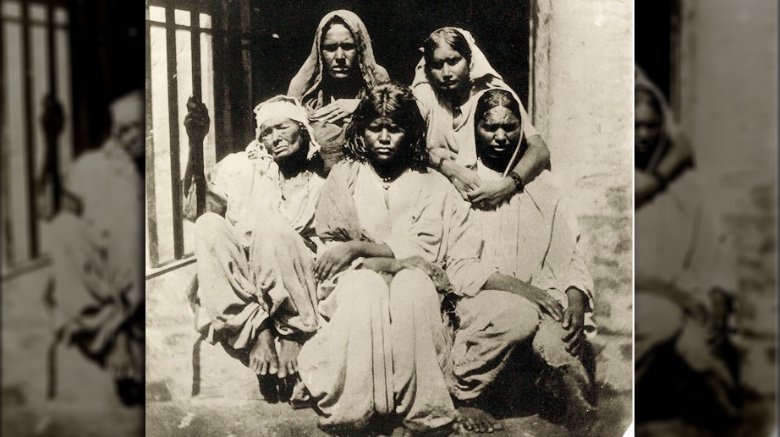

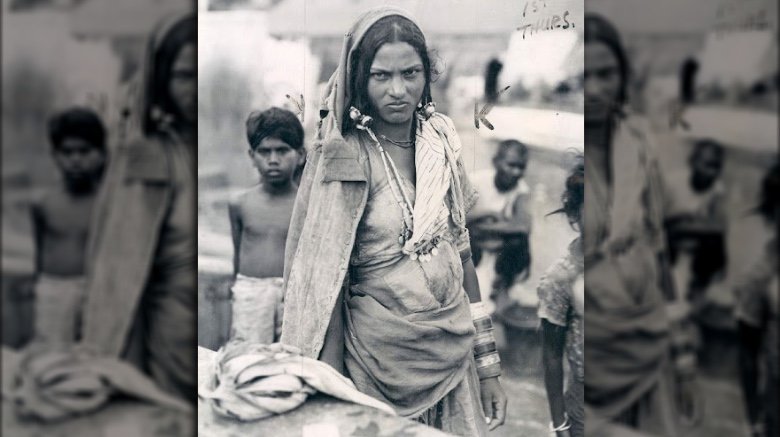

What life was like for women in British India

Okay so colonialism stank and it benefited very few Indians, and as much as we'd like to be able to put that to bed so we don't have to argue about it, it would be wrong to not acknowledge the few small improvements that happened under British rule.

India's two dominant religions had not-very-liberated ideas about women's rights. In both traditions, women were secondary to their husbands. In the Hindu religion, they existed only to procreate and provide company for men, and in the Islamic tradition, men were allowed to hit their wives or ditch them if they got bored with them. Female infanticide was common, and so was child marriage.

When the British Crown took over the government from the East India Company in 1858, Queen Victoria proclaimed the British would not interfere in Indian customs. But by 1870, the British had decided to act against female infanticide, and a bill was passed banning the practice. Many British were also critical of child marriage, and supportive of equal education for men and women. According to The Huffington Post, the British also translated and made widely available some of the old Hindu texts, which were generally a lot more supportive of women's rights — and that filtered back down into Hindu society, which ultimately resulted in more autonomy and liberty for Hindu women. So it was not all terrible things done by the British. Just mostly terrible things.

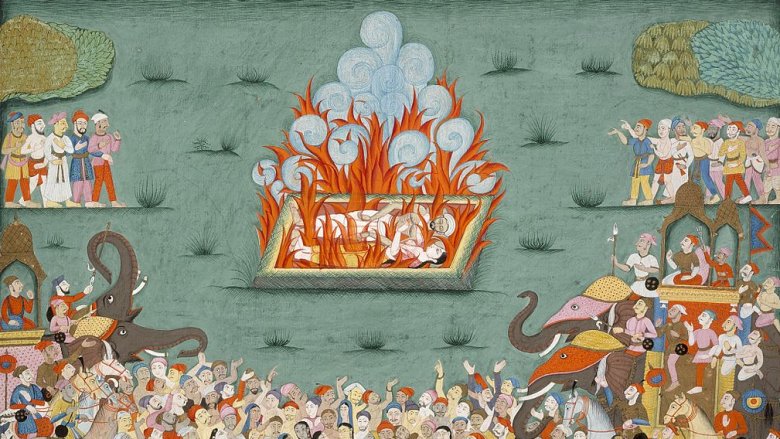

Also there was the whole not having to throw yourself on a funeral pyre thing

Widowed women in "upper caste" Hindu families got a huge boost in their standard of living under British rule in that they got to, you know, live. Before the arrival of the British, it was a common practice for a woman to throw herself on the funeral pyre of her husband — in fact it was actually expected and many women did it willingly, mostly because women who didn't participate spent the rest of their lives living in shame and humiliation.

The roots of this awful practice were mostly financial. A wife stood to inherit her husband's possessions after his death, but if she was no longer alive, then his possessions would go to his male family members. So it was in the interests of his male family members for her to burn to death alongside her husband's corpse. Nice.

According to The Huffington Post, an activist named Raja Ram Mohan Roy vigorously worked to end the practice of "widow immolation," but he got help from the British, especially from Christian missionaries and Sir John Malcolm, the governor of the Bombay Presidency. In 1829, the practice of widow immolation was banned, although 10 years later religious protesters convinced authorities to add an amendment distinguishing between "voluntary" and "forceful" immolation ("voluntary" was evidently a-okay). By 1861, though, Queen Victoria had issued a general ban on the practice and that was the official end of the horrible tradition.

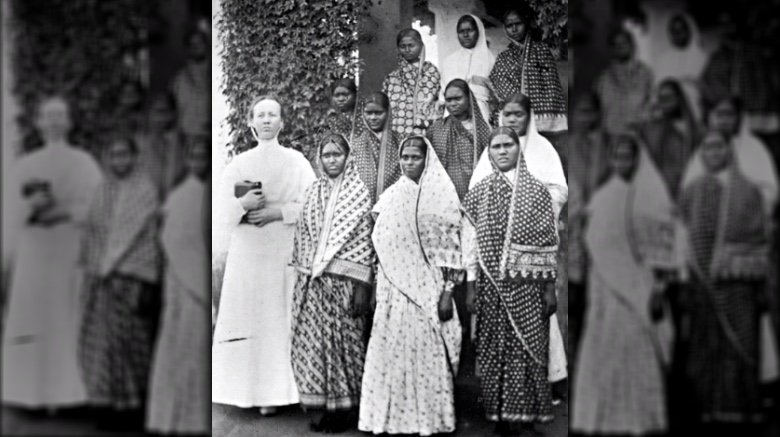

Our charter school is better than yours

Before the arrival of the British, the Indians did have two educational systems already in place — one for the Hindus, and the other for the Muslims. According to Nauman Tahir's paper The Aims and Objectives of Missionary Education in the Colonial Era in India, both indigenous systems were focused more on spiritual and classical education rather than practical education, and the schools were only for boys (girls were often educated at home).

When the East India Company took over Bengal in 1765, it decided against promoting education among the people of India, and it wasn't until its Indian officers urged it to reconsider that it rolled its eyes and did a couple of not-very-enthusiastic things in the name of public education. Mostly, it set up language schools, but even that was self-serving — it was in the interests of the East India Company for Indians to be schooled in the local dialects. It wasn't until the Charter Act of 1813 that there was a specific plan in place and an acknowledgment of the Indian peoples' right to education.

From there, we can argue about whether the indigenous systems or the Western one were superior, and whether Indian children benefited more from one than the other. It's certainly a little paternalistic to say the indigenous system needed to be replaced; on the other hand, it's probably true Western-style education gave Indian kids opportunities they wouldn't have had under the old systems.

It was his fault you murdered him

The British also brought their system of justice to India, and it maybe worked reasonably well when it was evaluating cases of Indian on Indian crime. But whenever the British controlled justice system saw a case involving an Indian versus a British citizen, the courts tended to always favor the British citizen. How surprising.

According to The Guardian, a case involving a British perpetrator and an Indian victim would nearly always be decided in favor of the British perpetrator. The murder of an Indian by a British person would always be ruled an accident, but in the reverse scenario, it was always a capital crime. The courts would also find new and creative ways to deflect blame — for example, if an Englishman kicked an Indian in the abdomen and the Indian died from a ruptured spleen, it wasn't the Englishman's fault because the Indian clearly had an enlarged spleen as a result of malaria infection. And the sentencing was pretty disproportionately unfair, too. A white man convicted of killing his Indian servant (on those rare occasions when he did get convicted) might serve six months. In fact, during the many years of British rule, thousands of Indians were murdered by British colonists, but only three white men were ever executed for killing Indians. But hey, give credit where it's due, it could have been zero white men (sarcasm).

Life expectancy in British India was abysmal

If you want to gauge the overall health of a community, life expectancy is a useful tool. Generally speaking, when life expectancy goes down, there is something seriously wrong within that community. And when the British took over India, life expectancy for the average Indian didn't just go down, it dropped by 20 percent all the way down to 32 years. Just put that into perspective, life expectancy for the average American today is around 79 years. If there was a sudden drop as bad in modern America as it was in British India, people would suddenly barely be living into their 60s, rather than looking forward to making it to 80.

According to the Conversation, under the British Raj — which is the term used to describe the post-East India Company era between 1872 and 1921 — life expectancy for Indians dropped but honestly, it wasn't that great during the reign of the East India Company, either. After India finally achieved independence, average life expectancy went skyrocketing up, far surpassing anything enjoyed under the British Raj or the East India Company. Today, Indians can expect to live about 27 years longer than they did under British rule. So yeah, something was seriously wrong in British India.

India's caste system still sucks, though the British kind of improved it

Just about every country has some kind of class system — in the United States it's based solely on economics, and we only talk about three different classes: lower, middle, and upper-income. But India's system is a class system gone totally haywire, and by the way it still exists and has existed for more than 3,000 years.

According to the BBC, in the caste system, people are divided into hierarchical groups based on the kind of work they do. There are four main groups: The Brahmins, who are the teachers and intellectuals, the Kshatriyas, who are the rulers and warriors, the Vaishyas, or traders, and the Shudras, who do all the menial jobs. But those four castes are further divided into 3,000 castes and 25,000 sub-castes, and then there's a final group: The Dalits or "untouchables," who don't belong in any caste. Also, there's no way to escape your own caste like ever, so there's that.

The British mostly strengthened the caste system, but they also disagreed with the treatment of the lower castes and the untouchables, and many of those people became educated and actually accumulated wealth under British rule. Some were even able to pass as members of the higher castes. Still, you really only saw an improvement in your life if you were able to become educated and wealthy — the poor still suffered under the forced segregation of the caste system.

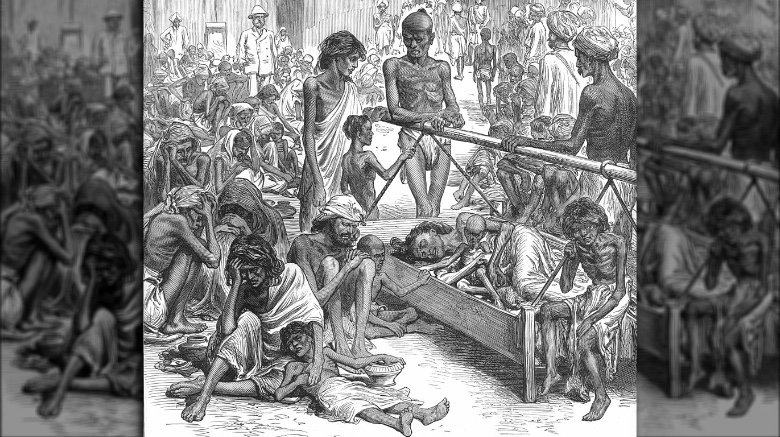

There were 31 devastating famines in India under British rule

Even today, you'll hear people say famine is an act of God or nature, something no one can control or fix until nature finally decides to undo it. But is that's an overly simplistic, dismissive, and frankly not very insightful assessment of the complex set of circumstances that have to come together in order for a famine to occur.

According to YourStory, in the 2,000 years before the British arrived in India, there were 17 famines, which equals roughly one every 118 years or so. In 120 years of British rule, there were 31, which is closer to one every four years. So there has to be some causative association between British rule and all those extra famines, and you don't really have to dig very deep to find out what it is.

The British occupied India for one reason and one reason alone: economic gain. Before the arrival of the British, Indian farmers had been growing mostly food crops like rice and vegetables, but rice and vegetables aren't terribly profitable as far as exports go, so the British started compelling farmers to grow higher value crops like poppy and indigo. But here's the problem — you can't put your surplus of poppy and indigo in your basement to fall back on during a not very fruitful season. So when an especially dry season happened and crops failed, starvation set in almost immediately and many Indians weren't able to ride it out.

They also raised taxes ... to recoup their own losses during the famines

The Indians were already dying because they had no food stores to see them through hard times, but as they were dying the British were banging down the front door demanding their taxes. Before British rule, Indian leaders charged between 10 to 15 percent of each peasant's cash harvest, and they would usually waive the people's taxes during times of famine.

According to YourStory, the British were not nearly so sentimental. When they took over control of the government, they raised taxes to a whopping 50 percent, which means even if the peasants were growing food crops there wouldn't have been much left after taxes to put in a store room for later. Then the dry weather and crop failures happened, people started dying, and the British said to themselves, "Hmm, how can we improve things for these farmers?" Just kidding. Actually, they said to themselves, "Hmm, how can we recoup some of our own losses from all of these dead farmers?" So they raised taxes from 50 percent to 60 percent. And during famine years, the British kept on flourishing while people all over the nation they were supposed to be protecting starved to death in their homes. Tell us again how colonialism wasn't so bad.

The railroad was really not a great thing for India

People who argue in favor of colonialism (and yes there really are people who still say colonialism was a good thing), will frequently cite infrastructure as something great the British did for India. One often-cited example is the introduction of the railroad, and yeah, there probably are instances where access to high-speed travel was advantageous for the locals. You can reach hospitals faster, for example, and you can move products from one place to another much more efficiently, thus expanding your customer base. That is, if the British aren't just taking all of your product and selling it to their own customer base.

But making life easier for the people of India is not even the reason why Britain introduced the railroad. The main motivation for bringing that particular technology to the Indian subcontinent was so the British could efficiently move troops from one place to another, which made it easier for them to put down small rebellions and to control the local people in general. Also, the railroad allowed them to easily transport food out of farming regions, which they did during times of plenty and also during times of famine. In fact according to The Conversation, mortality rates during the famines of 1876 and 1896 were highest in regions served by the railroad. So, yeah.

Divide and rule

Take a note, America. Unified people are a lot more difficult to rule than people who are divided. The British could not have conquered half the known universe if they didn't understand that simple fact. And it was actually policy during British rule to sow dissent between the two primary religious groups in India — the Hindus and Muslims. Because if you can promote fighting amongst the people, then the people will be distracted by their imagined enemy, and not so concerned about you anymore. Also, a divided people aren't in much danger of banding together to take you down, so you can safely rule them while mostly not doing the things that make the citizens of other nations respect and appreciate their leaders.

Britain's policy of dividing the nation even had a name: It was called "divide and rule," and it worked rather excellently for most of the time the British were in power. According to The Guardian, in the early days the British deliberately created antagonism between Indian princes, and later they used the caste system to further divide the population and create a sense of disharmony in the indigenous population. Most of all, though, they nurtured the division between Hindus and Muslims, and that division is one of Britain's lasting legacies. When Britain finally pulled out of India in 1947, it left behind a populace who still, for the most part, couldn't set aside the differences Britain had worked so hard to promote.

But what about all the democracy?

Democracy wasn't a thing in India before the British, and people who pine for the days of colonialism are pretty sure that's evidence the British did a lot of good while they were controlling India. Okay, but The Guardian says the facts don't really bear that out — the colonizers actually worked to undermine Indian politics and destroy any institution that might have otherwise resembled democracy. The British controlled everything, from tax collection to the justice system, and the Indians really didn't get a say in any of it.

When the British Raj took over from the East India Company, they threw a couple of crumbs to the indigenous population — a select few educated, upper-class Indians got to sit on a "legislative council," but those were not elected positions and the people who held them had no real power.

By 1920, Indian councils finally had elected representatives, but the people who were permitted to vote in those elections were members of a tiny, elite group — in fact the Guardian says only about one in 250 Indians had voting rights. Also, the Indian representatives only got to vote on stuff the British didn't care about, you know, like health care and education. The British were still in charge of the important things, like collecting taxes and making sure colonists got away with their crimes. So yeah, if that was democracy, well, there's a great democracy in North Korea we'd like to tell you about, too.