We Finally Understand Why The Aztecs Disappeared

For 200 years, the Aztec Empire thrived in what is now modern Mexico. They lived in a swampy, generally inhospitable landscape, and yet they were one of the most advanced civilizations of their time. They didn't have access to iron or bronze, but they made ingenious use of stone and copper. They made drills out of reed or bone, they understood mathematics, they used a 365-day calendar, and they were one of the first cultures in the world to require that all children receive an education.

In the 15th century, there were 25 million people living in the Aztec Empire. But 100 years later, there were just 1 million left. What happened to the Aztecs? We know the Spanish conquistadors had something to do with their demise, but it wasn't just those nasty European diseases that led to their ultimate downfall. It was a combination of horrific moments in history and the horrific actions of terrible people, with some nasty diseases thrown in for good measure. Until recently, we haven't really had a clear picture of what dealt the final blow to the Aztec Empire, but recent discoveries are finally shedding some light. So here it is at last, the awful truth about why the Aztecs disappeared.

Conquistadors gotta conquer

Like pretty much all Europeans of the time, the conquistadors were hell-bent on ruling the world. According to History, the first European to lay eyes on Mexico was Francisco Hernandez de Córdoba, who arrived in 1517 with three ships and 100 men, decided that wasn't quite enough, and headed back to the Spanish colony in Cuba with a report on what he'd seen. The Cuban governor responded by sending a larger force to Mexico, where they set up a settlement and immediately began training for conquest.

In November 1519, Hernán Cortés reached the Aztec Empire. He was greeted as an honored guest, which was cool with him because it meant he'd be able to take the entire civilization quickly and treacherously. The Aztecs had inferior weapons, so subduing them was not a huge problem for Cortés.

The Spanish were smart (and sociopathic) enough, though, to understand that to truly conquer a civilization, you need to take out all of the people in power. So their next step was to murder a bunch of nobles, which they did during a ritual dance (classy move, guys). Later, the Aztec ruler Montezuma died under "mysterious circumstances," but everyone can probably guess what those mysterious circumstances entailed.

But in 1520, Cortés briefly left the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlán, which at the time was one of the largest cities in the world, in order to deal with (of all things) another conquistador. According to Ancient Origins, the Aztecs took the opportunity to revolt, and by the time Cortés had returned to the city, the Aztecs had pretty much taken it back. Cortés didn't get the hint, though, and he quickly began plotting his recapture of the city. He forged alliances with local tribes, gathered an army, built ships to give himself an advantage on Lake Texcoco, and by May 1521, he was ready for action. And after a 93 day siege, the city fell to the Spanish once again.

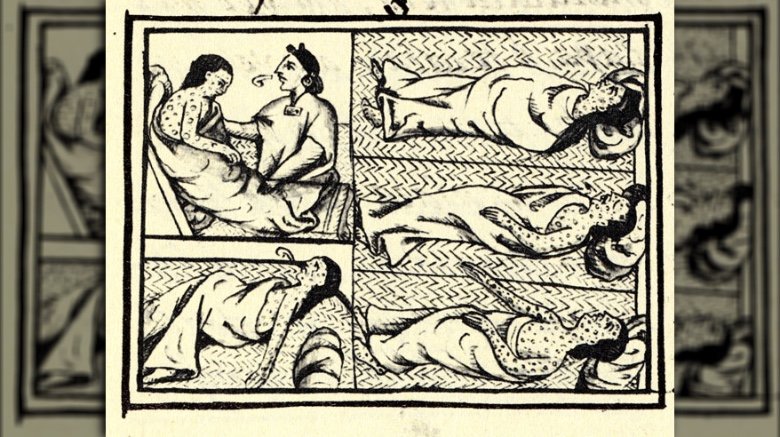

There were horrible, horrible diseases

When the conquistadors took over the city of Tenochtitlán, one of their keys to victory was smallpox. The city fell in just 93 days largely thanks to an epidemic that swept through the Aztec population. Obviously, smallpox showed up in South America courtesy of the Spanish, but that wasn't the only disease they brought along. The conquistadors also introduced the Aztecs to things like mumps and measles, too. But of the three, smallpox did most of the damage.

According to PBS, the smallpox epidemic that helped to take down the capital city spread from the coast of Mexico and eventually reduced the population of Tenochtitlán by a whopping 40 percent. Smallpox kills roughly 1/3 of the people it infects, but it's even worse than that. Another 1/3 of smallpox victims usually go on to develop permanent blindness, which means that the population of the capital city wasn't just reduced in numbers, but also in its fighting effectiveness.

Smallpox was a bad disease among Europeans, but it was even worse for the Aztecs because no one on the continent had ever been exposed to the virus, and therefore, they had no natural immunity to it, nor did they have medicine to help them combat it. "As the Indians did not know the remedy of the disease, they died in heaps, like bedbugs," wrote a Franciscan monk who was with Cortés during the whole ugly affair. Nice analogy, father.

A mysterious disease of unknown origins killed a ton of Aztecs

Smallpox devastated the Aztecs, but it wasn't the end of them. However, we've known for some time about the epidemic that really did them in. Historically, it's been referred to as "cocoliztli," which is an Aztec name meaning "pestilence." But for a long time, we didn't know what the cause of the illness actually was, even though it was responsible for the deaths of between seven and 17 million people in South America. The disease swept through Mexico and Guatemala in the latter part of the 16th century, decades after Cortés' conquest of Tenochtitlán. According to The Guardian, it killed 80 percent of the population within five years, and it was one of the worst plagues in history, similar in scale to the bubonic plague epidemic that killed 25 million people in Europe during the 14th century.

A historian from the period described the extent of the devastation, writing, "In the cities and large towns, big ditches were dug, and from morning to sunset the priests did nothing else but carry the dead bodies and throw them into the ditches."

For a people who were already devastated by smallpox and conquistadors, cocoliztli must have been both terrifying and demoralizing. Only a real optimist could witness such a thing and not see it as the beginning of the end, and it's probably safe to say there weren't a lot of Aztec optimists left in the world at the time.

Scientists have had a difficult time identifying the cause of the epidemic

The first cocoliztli epidemic happened in 1545, and it was so devastating that it forced the abandonment of entire villages, including a Mixtec village in Oaxaca, where researchers uncovered skeletons believed to have been victims of the first occurrence of the disease. A second outbreak hit in 1576, right around the time survivors were probably starting to relax and think the pestilence was a thing of the past. According to The Guardian, the second epidemic killed half of the region's surviving population.

It wasn't until this century that researchers finally started to put two and two together, based on historical accounts of the disease and the high death toll. In 2006, research published in FEMS Microbiology Letters examined census data from 1570 and 1580, and they found a population loss of 51.36 percent, which is pretty astonishing over such a short time period. The research also determined that the epidemic began in the valleys of central Mexico, and although losses were heavy in the indigenous population, the Spanish population was hardly affected at all. This research identified cocoliztli as a probable cause for the final collapse of the Aztec culture, though it was unable to precisely identify the pathogen responsible for the disease.

The symptoms of cocoliztli make human sacrifice start to sound pretty good

Cocoliztli baffled scientists for a long time, largely because its symptoms didn't seem to correspond with any known disease. According to The Atlantic, some scientists suggested it was a hemorrhagic fever, similar to Ebola or yellow fever. Others thought it might've been spread by rodents, like bubonic plague.

Franciscan friar Fray Juan de Torquemada, who witnessed the epidemic first-hand, described the fevers as "contagious, burning, and continuous, all of them pestilential, in most part lethal." He then went on to describe specific symptoms, saying, "The tongue was dry and black. Enormous thirst. Urine of the colors sea green, vegetal-green, and black, sometimes passing from the greenish color to the pale. Pulse was frequent, fast, small, and weak — sometimes even null. The eyes and the whole body were yellow. This stage was followed by delirium and seizures. Then, hard and painful nodules appeared behind one or both ears along with heartache, chest pain, abdominal pain, tremor, great anxiety, and dysentery."

Yikes.

Death usually occurred on the fourth day, which frankly sounds like way, way too much time. Wait, didn't the Aztecs practice human sacrifice? Because at least when you get sacrificed to the gods, you get to die in honor and glory and the only really terrible thing that happens to you is the whole ripping out of the heart thing, which sounds pretty danged good compared to four days with a black tongue, painful ear nodules, and dysentery.

We finally know the cause of cocoliztli

You've been in suspense long enough. What exactly was cocoliztli? Scientists finally think they've figured it out, and you'll probably be stunned by their conclusions: It was likely a form of Salmonella enterica. Yes, it's the same disease that makes you obsessively compulsively wash your hands every time you come within a few inches of a piece of raw chicken. Only the Salmonella we all know and despise typically only confines us to the bathroom floor for a couple of days, while we launch the contents of our stomachs out of one or both ends.

According to The Atlantic, scientists finally arrived at this conclusion after they examined DNA in 11 different skeletons uncovered in the cemetery of an abandoned Mixtec village in southern Mexico. Teeth are useful for identifying pathogens because the insides are full of soft tissue and blood vessels, and any pathogens that remain there after death are protected from decay by the hard enamel on the outside of the teeth. Researchers sequenced all the DNA they could find in each sample, and then used that data to generate a list of bacteria that were present in the teeth. Salmonella enterica was the one they kept finding.

One of these bacterium is not like the other

Today, Salmonella outbreaks are typically confined to people who eat food from contaminated sources, and they're usually very quickly identified and contained. They also cause mild symptoms, at least compared to the symptoms described by contemporary accounts of cocoliztli. The Atlantic says it's possible that Spanish-style agricultural practices contributed to the spread of the disease, so its unlikely that a similar outbreak could happen today, since we live in a system of tightly regulated agriculture that makes it a lot easier to prevent Salmonella outbreaks and control them when they actually do happen.

The type of Salmonella that killed the Aztecs isn't the same as the one that lurks in meat packing plants and factory chicken farms, either. It's a subset called Paratyphi C, which is similar to a rare modern type that has a 10 to 15 percent mortality rate. Paratyphi C causes an enteric fever nearly identical to typhoid, which is why a lot of scientists once believed that cocoliztli and typhoid were the same thing.

Some scientists still don't think it was Salmonella that killed off the Aztecs, though. There are no other historical incidents of Salmonella causing an outbreak quite so deadly, so if the authors of the recent study are correct, the Aztecs were just really unfortunate to encounter such a rare and devastating illness just as they were recovering from the Spanish conquest and other deadly diseases like smallpox.

We probably won't ever have a complete picture of why the Aztecs disappeared

The trouble with trying to diagnose a disease so many years after the fact is that it's impossible to really know the whole picture. Your knowledge is limited to just what you can pull out of the teeth of people who died hundreds of years ago and what you can read in the historical accounts that may or may not have been written by people who had any idea what they were talking about. So all the best researchers can really do is say "Okay, we found Salmonella in the teeth of these people who died around the same time as the epidemic," but they can't really say for sure that the Salmonella is the whole story behind what killed them.

We do know that samples taken from the teeth of people buried in the same cemetery as cocoliztli victims who died before European contact didn't show any evidence of Salmonella infection, but all that means is that those particular individuals didn't encounter the bacteria before they died.

According to The Atlantic, it's possible that other diseases making the rounds at the time exacerbated the Salmonella, or even that the Salmonella exacerbated some other as yet unidentified disease. The problem with the tooth examination strategy is that it can only look at DNA, but some viruses don't have DNA — they have RNA. So if the people scientists examined died from an RNA virus, researchers wouldn't be able to tell.

Europeans may not have been to blame

Naturally, we're going to want to blame Europeans for the introduction of this particular strain of Salmonella, because duh. Europeans pretty much messed up everything they touched between 1492 and 1944 or so. The fact that cocoliztli was so devastating and had such a high mortality rate, combined with the fact that it disproportionately seemed to affect indigenous people while having little or no effect on the Spaniards who were living in the area, does seem to suggest that it was of that European origins.

But not everyone agrees. Francisco Guerra, who wrote a research paper on Aztec medicine, says there's some a chance that the epidemic might've existed before the arrival of the conquistadors. There's evidence that epidemics contributed to the first migrations into Mexico, and an epidemic may have contributed to the fall of the Tula kingdom, which preceded the Aztecs. Some of the epidemics sound similar to the cocoliztli of the post-European era, and some were even called "cocoliztli," although the term was originally used to describe epidemic disease in general and not something specific.

The Aztecs had to deal with droughts

Just in case the Aztecs weren't already starting to suspect that the gods were out to end their civilization, the two cocoliztli epidemics coincided with long periods of drought. So not only did the Aztecs have to deal with the fact that so many of them were dying from this terrible disease, there was also the fact that they couldn't grow enough food to feed the people who were left over. Of course, probably not many of them really felt like going out in the field between bouts of turning yellow and developing weird pustules behind their ears, but still. The epidemic did make people thirsty, and thirsty people need water, and drought means there was none of that, either.

According to a 2002 study published in Emerging Infectious Diseases, tree-ring evidence suggests that the two cocoliztli epidemics coincided with the worst North American drought in 500 years, which stretched all the way from Mexico to the boreal forests of Canada and from the Pacific coast to the Atlantic. The drought likely made the epidemic worse, not because it changed the contagion, but because when people are already suffering, well, it's not like drought is going to improve anything.

The Aztecs aren't really gone, though

Before you start feeling really terrible about the demise of the Aztecs, here's a hopefully comforting final note. The Aztecs aren't really gone. Yes, it's true that they were conquered and beaten back by the conquistadors, and it's true that they lost a huge proportion of their population to disease, but nearly every horrible catastrophe has at least a few survivors.

According to Yahoo! News, in 2017, archaeologists in Mexico announced that they'd found the remains of a dwelling where upper class Aztecs lived following the Spanish conquest. The scientists who uncovered the dwelling said it was likely that the people who lived there were first and second generation descendants of the citizens of Tenochtitlan.

The Aztecs moved on from there, too. Today there are 1.5 million Nahua — the descendants of the Aztecs — living in small communities in rural Mexico. Many are farmers and craftspeople, and most attend Christian churches, although their religion has a few vestiges of the old Aztec ways, including traditional medicine and the occasional sacrificed chicken. So its safe to say that Aztecs didn't really disappear, they just went somewhere where there weren't any Spanish conquistadors or cocoliztli. Which, in retrospect, was probably the best idea they ever had.