Why Are Greek And Roman Myths Depicted In Famous Christian Art?

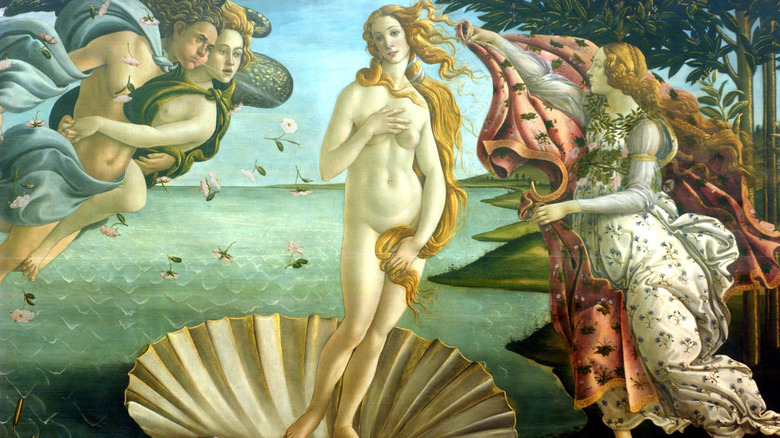

Certain pieces of art are so ubiquitous and well-known that folks might say, "Hey, I know that one!," without knowing anything about its history, creation, artist, name, the era and area it came from, and so forth. Take the profoundly gorgeous "Birth of Venus" by Italian painter Sandro Botticelli (shown above). Painted in 1485 C.E., well before anyone could instantly learn about its story online, the work depicts the events following the birth of the goddess Venus (or Aphrodite to the Greeks). Its rich imagery shows Zephyr, the wind, blowing Venus to the island of Cyprus on a seashell, where the goddess of spring is waiting to clothe her. Botticelli, the painter, lived in Florence during the Italian Renaissance and, like those of his time, was Christian.

The last statement might not seem like a big deal. But, for a time and region steeped in Roman Catholicism and preceding the 1517 Protestant Reformation, it's pretty amazing that such "pagan" artwork existed. In fact, Greco-Roman mythological allusions didn't merely survive during the Italian Renaissance from about 1350 to 1600 C.E. — they thrived. Not Assyrian mythology, not Egyptian, not Norse, but Greek and Greek by way of Rome. There's a whole Western European cultural heritage connecting "classical Greece," as it's called — 5th and 4th-century Athens — to modernity. And it happened through Christianity and the transmission of ancient texts across all of Christendom, from the British Isles to Byzantium, starting with apostles like St. Paul after the crucifixion of Jesus and continuing all the way to the present.

Early church writers absorbed Greek thought

There's a long tradition within Christianity of not only tolerance toward the Greeks, their philosophy, and mythology, but acceptance too. This is consistent with the West's dual classical-Christian heritage, which defines it from the ground up. So much so that few moderns would bat an eyelash at how a predominantly monotheistic culture produced gorgeous works of art depicting scenes from another once-living religious tradition.

While we could drop into the past-to-present timeline at multiple spots to untangle the classical-Christian puzzle, it makes sense to start with St. Paul, the guy who penned about half of the books of the Bible's New Testament (13 or 14 out of 27). Paul was a well-educated Jewish man who wrote in Koine Greek, the common literary language of the time. Paul would have been fully versed in old and new Greek texts alike. He even uses Greek terms like "Hades" — poorly translated as "death" — in passages like 1 Corinthians 15, where he explains Christianity's new vision to converts using familiar ideas.

This is because, like all other early Christians, Paul lived within the Roman Empire, which itself took heavy inspiration from the Greeks in realms of art, religion, literature, architecture, and more. He was also likely influenced by Neoplatonism, a school of Greek-born philosophical thought that fused with traditions like Judaism to produce mystical Gnostic beliefs, which come out in Paul's writing. In other words, the classical-Christian connection was there from the beginning — and it only strengthened over time.

The Byzantine preservation of classical texts

No matter how strong the classical-Christian connection was, it wouldn't have generated works of art like "The Birth of Venus" nearly 1,500 years later without the preservation of traditions and documents, particularly those written in Greek. In order to save a declining Roman Empire, Emperor Diocletian split it into western and eastern halves in 293 C.E. Less than 20 years later, in 312 C.E., Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. In 330 C.E., he founded Constantinople — later Byzantium, and then Istanbul — as the new Christian head of the eastern empire in modern-day Turkey. This move altered history forever.

When the western half of the Roman Empire collapsed in 476 C.E., Byzantium carried on. Its Christianity evolved into what we know today as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, which uses Greek as its liturgical language, not Latin. Hence the continuity of ideas from early Christian texts to the subsequent medieval ages, using the Byzantine Empire as a go-between.

It was Byzantium that preserved works that we take for granted nowadays, including the original Greek writings of Plato, Aristotle, and some of the Neoplatonist thinkers who influenced St. Paul. Even as the western half of the Roman Empire fragmented into what would become the kingdoms of early Western Europe, Byzantium protected more than two-thirds of all classical Greek writings. Byzantine scholars examined these texts through a Christian lens, and in turn, Christianity took on their hue.

Medieval Scholasticism: taking lessons from pagans

Come 1054 C.E., the very complex sociopolitical tangle of the time resulted in Roman Catholicism in the west splitting from Eastern Orthodox in the east to become separate, standalone churches, i.e., The Great Schism. Both churches had different takes on various theological issues, with Orthodox Christianity being especially touchy about the dangers of icons becoming idols. But, both of them admired the classical world. Even by the 3rd century C.E., Logo's Word by Word quotes Christian missionary Clement of Alexandria as saying, "Before the advent of the Lord, philosophy was necessary to the Greeks for righteousness. ... Philosophy, therefore, was a preparation, paving the way for him who is perfected in Christ." In the 4th-century, historian and bishop Eusebius of Caesarea said that the Greek philosopher Plato was, "the only Greek who has attained the porch of [Christian] truth."

Following the Great Schism, theology and the classics in western Europe fused into one system of study at universities and cathedrals called scholasticism. Lasting from the 12th to 16th centuries, the scholastic age segued into the Renaissance and its explosion of interest in the ancient world. Legendary 13th-century Christian theologian St. Thomas Aquinas (1225 to 1274 C.E.) drew heavily from Greek philosophers like Aristotle to solidify scholasticism's joined classical-Christian approach. The same goes for figures like Florentine poet Dante Alighieri, whose work "The Divine Comedy" proved immensely influential to kickstarting the Renaissance. And in "The Divine Comedy" it's Virgil, the pagan Roman writer of the epic poem "The Aeneid," who guides Dante's pilgrim through Hell.

[Featured image by Jean Le Tavernier via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

The Renaissance: looking to the past for inspiration

At this point, it should be easy to see why there was no conflict at all for Christians during the Renaissance and beyond to portray characters and scenes from Greco-Roman mythology in their art. The Italian Renaissance started in Florence shortly after the death of Dante Alighieri in 1321 C.E., and lasted from about 1350 to 1600 C.E. Top to bottom, the Renaissance stemmed directly from admiration of the classical world and the wider rediscovery of the literary works of Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, and more. This admiration, combined with a rapid surge in advanced artistic and architectural techniques, ignited the soul of society and spread across Europe and the United Kingdom. The beauty of the past fostered the desire for beauty in the future, and critically, the belief that humanity could create such a future under its own will.

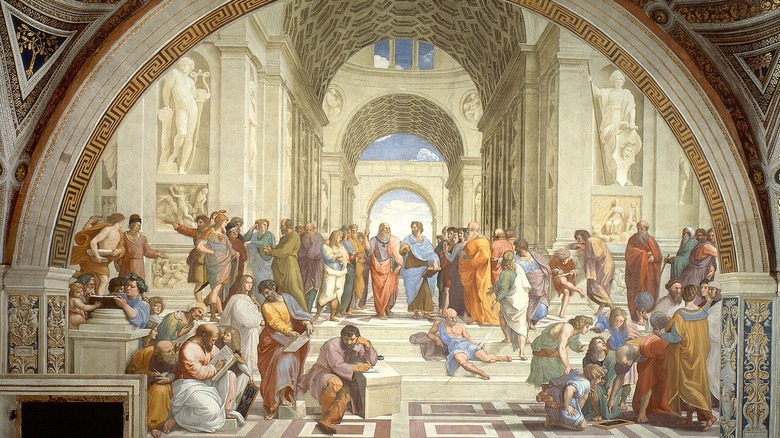

It's the Renaissance that gives us so many grand, important, long-lasting pieces of art recognized the world over. We mentioned "The Birth of Venus" by Sandro Botticelli, a piece by a Christian painter featuring a Greek deity. Other artists like the famed Michelangelo (1475 to 1564 C.E.) sculpted biblical figures like King David and painted scenes like God's creation of humanity on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Other painters portrayed classical and Christian pieces alike, like Raphael's (1483 to 1520 C.E.) monumental "The School of Athens" (seen above) or Leonardo da Vinci's (1452 to 1519 C.E.) historic "The Last Supper." Every subject was fair game, Christian or not, and rooted in the West's deep classical-Christian heritage.

[Featured image by Raphael via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

Neoclassicism: imitating the classics

The Renaissance went through numerous, small cultural phases as it paved the way for the Age of Reason, aka, the European Enlightenment movement (about 1685 to 1815 C.E.). The Enlightenment gave birth to modern democratic political institutions, medical advancements, and technological wizardry via the Industrial Revolution all in one. And nested within the Enlightenment sat another revival of classical stories, images, and themes in Christian countries dubbed the neoclassical age (about 1760 to 1860 C.E.). This revival kept those stories alive and gave us even more fused classical-Christian art.

As the name implies, neoclassicism was a reprised take on arts, architecture, literature, etc., based on classical subject matter and style. It was one the preeminent artistic movements in Europe at the time, focusing on "harmony, clarity, restraint, universality, and idealism," as Britannica says, and developed in part as a reaction to the highly ornamented, bright, and garish Rococo stylings en vogue during the same period.

While neoclassical art need not portray Greco-Roman myths exclusively, it often did. This is the case with revered sculptures like Antonio Canova's "Cupid and Psyche" from 1793. Other paintings started to reference not original classical sources, but Renaissance-era sources based on classical sources, like William-Adolphe Bouguereau's "Dante and Virgil in Hell" from 1850. Coming across as one of the finest examples of merged Christian and classical inspiration, it features a scene from Dante's "The Divine Comedy" showing the pagan Roman poet Virgil guiding Dante's pilgrim through hell.

[Featured image by William-Adolphe Bouguereau via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]