The 10 Most Powerful Native American Tribes In History

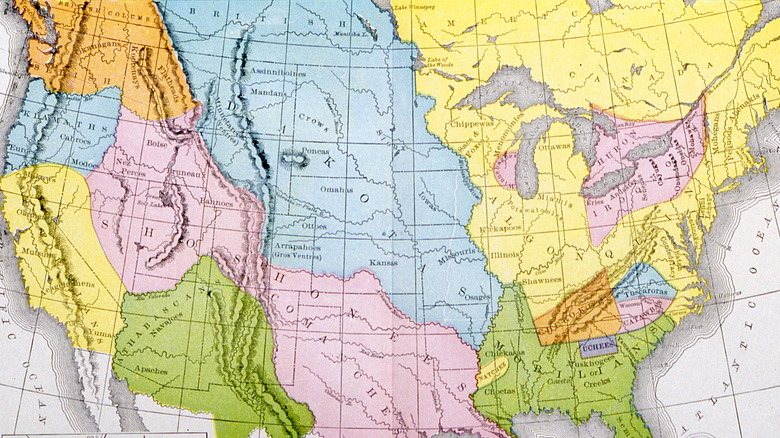

The vast diversity of Native American groups can be overlooked in the thumbnail studies many people receive in history classes. While in some cases Native history can be difficult to trace, given the lack of textual records, shifts away from original languages, and histories of displacement, what tribes have preserved and scholars uncovered presents a fascinating picture. With wide variations in language, lifestyle, and culture, the groups living in precontact America had cultures as complex and intriguing as their counterparts in the "Old World."

It's also important to acknowledge that Native American history didn't end with European contact and conquest. Native peoples have continued to resist, adapt, and make history into the current day, with groups from across the whole of the hemisphere pursuing their legal rights and maintaining their cultures and heritages. While their legal situation varies in every modern-day country, Native people and peoples remain and endure.

Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy)

The Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy, are a union of six (originally five) individual but related tribes of the eastern United States and southern Canada. The Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca joined one another in a loose, representative union sometime before the arrival of European colonists. When the French expanded along the St. Lawrence Valley in the late 1600s, they met fierce resistance from the Haudenosaunee, who didn't like the French allying with their rivals, the Huron and the Algonquins.

By the time the Tuscarora joined in 1722, the confederacy was a British ally, both because of their shared French enemy and because the Haudenosaunee liked to shop in Albany. (Presumably it was more fun then.) The Haudenosaunee split over whether to support American independence, and the British-loyalist section of their forces lost in battle to Patriot forces.

The Second Treaty of Fort Stanwix deprived the Haudenosaunee of much of their political power, but the confederacy remains active today — and its member tribes still meet in Grand Councils to discuss major issues and events. They might be going to the Olympics, too. Lacrosse has its origins among Indigenous groups including those that make up the Haudenosaunee, and the team they field, the Haudenosaunee Nationals, is a force in international tournament play. The team hopes to play as a nation in the 2028 Olympics. The International Olympic Committee is reluctant to allow a team from an entity without a national Olympic committee, but both the Haudenosaunee and President Joe Biden have been lobbying.

Comanche

The image of Native Americans as mounted warriors is so pervasive in popular culture that it's easy to forget that horses had been extinct in the Americas for thousands of years before Europeans reintroduced them. This didn't stop some groups from adapting quickly when this new means of moving goods and making war trotted in, and a number of Native groups became excellent users of the horse.

The Comanche were one of the greatest of these riding nations. Originally from the inland northeastern United States, the Comanche acquired horses in the late 1600s and began moving southeast, toward buffalo and trade with French outposts and away from the well-armed Blackfoot and Crow peoples. Though they remained nomads, Comanche groups eventually came to dominate a wide belt of the Southern Plains.

Comanche raids so flustered the Spanish governor of Texas that he was forced to buy them off with gifts — and, under the Spanish-Comanche Treaty of 1785, promises of more. When Spanish bribes were late, the Comanche stole from Spaniards to have goods to trade with American settlers. The Comanche continued to badger independent Mexico, then (after the government changed again) fought a war with the Republic of Texas, losing but not without a fight. Unconquered, they took advantage of the American Civil War (two governments later) to increase raiding, eventually pushing back the line of white settlement within Texas. This success didn't last, and after 1874 the again-unified United States was able to force the Comanche onto reservations. Despite struggles in the reservation era, the Comanche today operate a tribal nation based outside Lawton, Oklahoma.

Natchez

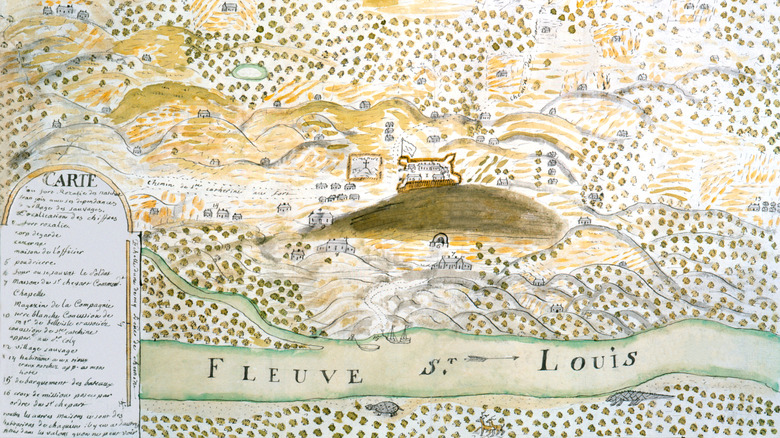

The Natchez tribe was one of the most powerful Native groups the French faced in the lower Mississippi Valley. Several loosely unified villages of Natchez speakers and Tunica allies operated under a Grand Village, where the hereditary leaders with titles "Great Sun" and "Tattooed Serpent" lived. The Natchez were a mound-building culture, like others in the Gulf South, and built enormous mounds for residential and ceremonial purposes by transporting soil and compacting it and other "filler," maintaining the structures regularly.

Initially friendly with the French (though some villages traded with the English), the Natchez became less content as more and more settlers began moving into the area. The French station of Fort Rosalie, in particular, was very close to the Grand Village. When in 1729 a new governor demanded the Natchez evacuate in order to establish a plantation — the French were now bringing in a considerable population of enslaved people — the Natchez were unwilling to comply. They went into Fort Rosalie on a routine trading mission, got some new guns... and fired them at the colonists, killing most of the adult male free population and capturing many women, children, and enslaved people.

French Louisiana convulsed in fear; the governor massacred an unrelated tribe in order to... broadcast the official French policy of indifference to Native lives. The French and their Choctaw allies attacked the Natchez in 1730 and 1731, selling many into slavery in French Saint-Domingue. Survivors took refuge with other southeast tribes and generally shared their fates, but the Grand Village, now in downtown Natchez, stands today as a National Historic Site.

Cherokee

The Cherokee were one of the most populous tribes in what became the southeastern United States and remain a prominent Indigenous group in the United States today. From their homeland, the Cherokee participated in a complex trade network of Native groups. When the British arrived in South Carolina and Georgia, the Cherokee proceeded to trade heavily with the newcomers. The Cherokee maintained a shaky alliance with the British during the Seven Years' War and American Revolution, with some continuing to fight against American forces and settlers well after the British defeat.

In order to resist ongoing American encroachment, the Cherokee consolidated under a Western-style government with a permanent capital, written constitution, and police force. They also became one of the first Native groups in North America to use written language: A Cherokee man named Sequoyah, who only spoke Cherokee, created a writing system completely unrelated to any other world alphabet but perfectly suited to writing Cherokee. (He then had to convince his fellow tribe members that his writing system was not witchcraft.) These cultural changes won the Cherokee the dubious accolade of being a "civilized" tribe, but that didn't stop Congress from passing the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The decree was enforced in 1838 despite a Supreme Court injunction, and most Cherokee were expelled from their homelands to what became Oklahoma on a forced march now remembered as the Trail of Tears. (Some Cherokee remained in eastern North Carolina and exist as a separate tribal organization today.)

Despite this loss of their homeland, the Cherokee remain a populous Native group with a large tribal territory; in both the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma and in places like Chattanooga in their former homeland, you can still see Sequoyah's writing system on signs.

Pueblo peoples

The Pueblo peoples of New Mexico are not one group but a linguistically diverse constellation of neighboring groups who share similar lifestyles. Balancing hunting, gathering, and agriculture to meet their needs, 70 or so independent villages existed before the Spanish arrival in the Puebloan area. (Puebloans and their ancestors constructed the remarkable, if dizzying, cliff dwellings that enchant visitors to their area of New Mexico.)

The Spanish arrived in the 1540s and ruled through self-reported violence and rape. The Pueblo peoples endured the Spanish yoke until the 1670s, when the Spanish executed some holy men and had others publicly whipped — which, if you're trying to make people angry enough to revolt against your rule, is a pretty good plan. One of the men who had been whipped, Po'pay (also spelled Pope in some texts) retreated to Taos Pueblo to think about how to drive away the Spanish for good. He sent knotted cords to each Pueblo group that agreed to join the rebellion: Leaders undid one knot a day, and when the knots were all gone, it would be go time.

That day was August 10, 1680. By August 21, the Spanish fled, minus some 400 dead. The Pueblo ritually cleansed themselves of Christian rites they had been forced to undergo and enjoyed 12 years of independence resulting from what the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center calls "the first American Revolution." Spanish forces returned and reconquered the region in 1691-92, forcing the Pueblo peoples again to adapt... but to Spanish colonizers now more cautious of Pueblo power. Today, a number of Puebloan groups still live in New Mexico, and while they face the challenges most Native groups do in maintaining their history and culture, they endure.

Guaraní

The Spanish arrived in what is now Paraguay and northern Argentina to find, nestled among other groups, over 1 million Guaraní, speaking either closely related languages or dialects of a single one and participating in complex trade networks with other Native groups. Initially friendly relations collapsed when the Spanish colonizers tried to force the Guaraní to work for them and convert to Christianity. (Imagine that not seeming friendly.) Many Guaraní died of illness or violence, some were forced into colonial systems, and some fled into the forests.

The real triumph of the Guaraní is in their language: The Guaraní language is the only language in the Americas to out-compete a colonizing language, with Paraguay effectively bilingual in Spanish and Guaraní and the language taught in schools across the country. Guaraní's endurance has not been wholly a feel-good story: Spanish missionaries used Guaraní as a means to communicate with other Indigenous groups, and later rulers of independent Paraguay used the language as an ingredient in nationalist programs. (Policemen allegedly shot people in the streets of Asuncion if they couldn't understand Guaraní.) Even with this history, however, Guaraní, even if it's been used for unsavory ends (like every language), represents Native persistence in the face of cultural assimilation — and it's even got a Wikipedia.

Moche

The Incas' predecessors as the major power in what became northern Peru, the Moche were master potters, architects, and engineers. Flourishing from about A.D. 1 to 800, they used the wealth and power they gained from their successful expansion to create a material culture that stands out as one of the most distinct and impressive of all the pre-contact Native American groups.

Moche artifacts are so detailed and numerous that they allow researchers to piece together significant information about this group, who didn't use written language and declined before encountering people who could and did record their beliefs or history. Elaborate Moche pottery often depicts animals or portraits — seemingly of specific people, as distinctive features, scars, and expressions imply. (Was this like having a Milli Vanilla lunchbox in the 1980s?) They also produced an enormous amount of graphic erotic pottery, suppressed by the Spanish but now prized by collectors and researchers — after all, if you know how people feel about sex, you know a lot about their worldview.

Etchings on other pots depict what seems to be a badminton-like game played with atlatls, hand-powered dart launchers used for hunting. According to Archaeology Magazine, archaeologist Christopher Donnan worked with modern atlatl users to try to recreate the game and made an important discovery: It was a lot of fun. The sporty, sex-loving Moche have left behind a number of mysteries, but we can say, unequivocally, that they were cool.

Inca

The exact origins of the Inca state are difficult to ascertain with certainty, but their dramatic rise began in 1438, when they exploded out from their homeland in the Cuzco Valley and quickly conquered many of their neighbors, occupying a state, Tawantinsuyu, that stretched down the South American coast from modern Ecuador to central Chile. They put into place a sophisticated internal organization and established a network of roads (and taxes), and so when the Spanish encountered them in the 1520s, they were the largest and most centralized state in South America.

The Inca did all this without inventing the wheel or written language, relying on llamas for transport through the hilly Andes and complex systems of knotted strings, called quipu, to record information. (The quipu is one of several writing systems that still haven't been entirely figured out; machine learning is currently being used to try to decode the few that survive.) Rich in gold and silver, the Inca might have been well suited to fight off the Spanish had they had another generation to consolidate their power, but an Inca civil war and the dislike of many of their subjects (pro tip: don't rely on the goodwill of "subjects") meant the Spanish would win... eventually, as Incas kept resisting in the Andean highlands for decades. Quechua, a descendant of their language, is among the most widely spoken Indigenous languages in South America.

Aztec

Initially wanderers, the Aztec — or the Mexica, as they called themselves — established what would become their state in 1325, after seeing an omen on an island in Lake Texcoco in central Mexico. This omen, an eagle eating a snake while perched on a cactus, has persisted to grace the flag of modern Mexico; this settlement grew into the ancient Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, the biggest city in precontact North America and the precursor of modern Mexico City.

Strictly speaking, the Aztec Empire was an alliance of three city-states, Tlacopan, Texcoco, and dominant Tenochtitlan. Tenochtitlan, with its temples, pyramids, complicated agricultural gardens, and, uh... racks of human skulls amazed the Spanish on their arrival in 1519. But they were far more than just conquerors and skull connoisseurs: The Mexica produced one of the few Indigenous American writing systems, and their ball game, played with rubber balls and imbued with ritual significance, continues to receive serious academic study and revival among Native-descended groups.

Like their counterparts the Inca, the sophisticated Mexica state might have been able to resist the Spanish onslaught if not for two factors: European diseases like smallpox and measles and local groups unhappy with Mexica domination joining the invaders. Tenochtitlan fell in 1521, but the Aztec legacy endured: Their language, Nahuatl, still has 1,500,000 speakers, and public works in Mexico City regularly have to pause due to the discovery of more Aztec artifacts.

Maya

The Maya of the Yucatan Peninsula and adjacent parts of Mexico and Guatemala rose in about A.D. 250 and flourished for centuries before undergoing a dramatic collapse shortly after 900. Not a politically unified group, the Maya instead organized themselves into independent city-states who traded and made war among each other. While the society never regained its complexity after its mysterious contraction, the Maya were far from extinct, with several hilltop cities remaining powerful until the Spanish arrival, and the religious systems remaining intact among the farmers and villagers in the lowlands. Climate change, war, and trade disruption have all been posited as causes for the abrupt end of the Mayan heyday.

But what a heyday it was. Mayan hieroglyphs were the most complete writing system ever developed by an Indigenous American culture, and even after the Spanish destruction of Mayan books, there's plenty of writing to study. The Mayans loved carving information into their buildings and painting richly colored murals, and scholars have learned much of the Mayans' history through these sources. (Delightfully, the man who made the most headway in deciphering this writing was an eccentric Ukrainian-born Soviet who preferred to be photographed with his cat.) Ancient Mayans with names like Lady Snake Lord of the Centipede Kingdom and Penis Jaguar can reach out through these traces and make themselves known to modern people — including the 5,000,000 people still speaking Mayan languages today.