Why The Vietnam War Was Worse Than You Thought

Over the course of American history, it's somewhat difficult to find a conflict that's more infamous and controversial than the Vietnam War. Amidst the messed up events of the Cold War, the U.S. sent increasing numbers of troops to aid South Vietnam in its fight against Communist North Vietnam; by 1954, war had officially broken out, and fighting would rage on for nearly two decades.

The longer the conflict continued, the more the American public actively detested the war. Horrific images from the front marred their screens, high casualty counts eroded support, and the seemingly endless fighting led citizens on the home front to take action against the government. Protests broke out across the nation in response to the drawn-out, unpopular war effort, and in some cases, violent responses by the police and armed forces against protestors only turned popular opinion more sour. By 1973, the U.S. did officially pull out of the war, with the conflict between North and South Vietnam ending two years later.

Nevertheless, the Vietnam War has maintained its infamous reputation over time, and you're far more likely to hear about its negative aspects than any positive ones. Even so, despite its already dismal reputation, the Vietnam War was actually even worse than you might currently believe, and for a number of different reasons than you might be aware of. Here are some of the darkest facts and effects stemming from it.

The long-term effects of chemical warfare

"Only you can prevent a forest" was the dark phrase uttered by those responsible for Operation Ranch Hand (via History), the mission to rain down chemicals like the infamous Agent Orange on Vietnam's forests and crops. Its purpose was to destroy the foliage where Viet Cong soldiers could hide and the fields used to feed them, and even in the short term, the operation trod on shaky moral grounds, starving the Vietnamese population and arguably even breaking international law.

The long-term effects were even worse, though, spanning the decades since its deployment. Millions of people were exposed to dioxins — known carcinogens — in the process. Those dioxins can enter the bloodstream and cause a number of different health problems, from cancer to reproductive issues to damage to the immune system. But the issues reached even further, with the children of those exposed to Agent Orange and similar chemicals often being born with major physical and mental disabilities — some children were born without eyes or parts of their brain and skull. There's even a possibility that the chemicals did substantial genetic damage that will carry on for multiple generations.

To make things worse, the U.S. has been loath to admit to a correlation between exposure and birth defects for fear of making reparations. Furthermore, the Vietnamese government has been hesitant to allow American research to take place, concerned that studies wouldn't conclusively prove a link, subsequently taking away their grounds to blame the U.S.

Childhood involvement in the war

Clearly, the civilian population of Vietnam was heavily affected by the war, but the effects on children were probably among the worst. Untold numbers of childhoods were interrupted, and many were left without homes and families.

Civilians constantly needed to uproot their lives and flee from dangerous zones. That situation made it easy for the Vietnamese Communist Party to paint U.S. soldiers as the enemy, simultaneously inundating young children with propaganda and instilling them with a strong sense of duty: to serve their country and fight against their enemies. Art competitions focused on wartime themes or encouragement to support family members who were on the front lines. Sometimes children were more involved, helping to build roads and fortifications or to put together supplies for soldiers.

But in the most extreme cases, the children themselves actually served as soldiers. Even kids as young as 13 were occasionally being taught how to take up arms, trained in the guerilla warfare methods that the Vietnam War has since become infamous for, or as spies and informants. And this wasn't an uncommon thing, with child soldiers being given official awards and titles, one of the known honors being "Valiant Destroyer of the Yanks" (via British Library).

The uncertain futures of mixed-race children

With the timeline of the Vietnam War being so long, American soldiers ended up starting up relationships with Vietnamese citizens, but the children born of those short liaisons ultimately found themselves with a long and hard road ahead of them. On the cultural front, Vietnam favored neither premarital sexual relations nor relationships with foreigners, so not only were those kids often unregistered, but they were often abandoned shortly after their birth, left behind at orphanages by their mothers and completely unaware of their fathers' identity.

The social stigmas surrounding their identity led to no small amount of cruelty. Other children teased them without thinking, adoptive families simply didn't want them, and in many cases, they found themselves uneducated and begging on the streets. Even Vietnamese Americans thought less of them, assuming (often incorrectly) that their mothers were prostitutes. For many of those kids, the dream was to somehow make it to America and find their fathers, but the lack of documentation has made that nearly impossible for almost all of them, with only 3% actually locating their birth fathers. What's more, both the American and Vietnamese governments wanted nothing to do with them for many years, with the former trying to absolve itself of any responsibility while the latter even went so far as to actively call them "bad elements" (via Smithsonian Magazine).

That said, many were allowed to immigrate to the U.S., forming their own communities and identity, with those who have found happiness taking pride in all that they've endured.

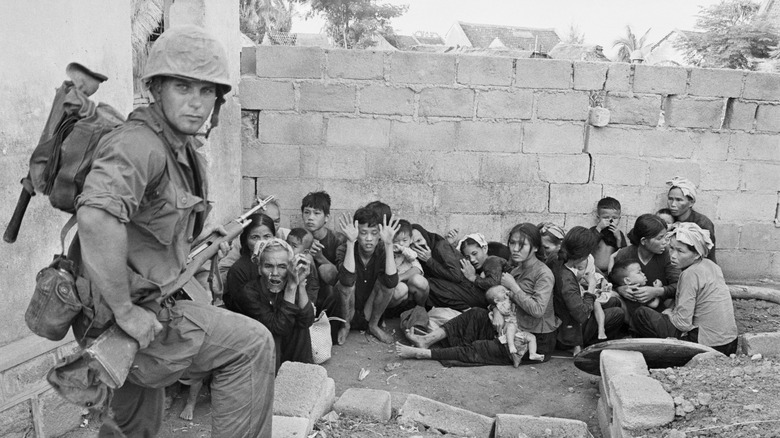

Massive civilian casualties

The Vietnam War was brutal, to say the least, and strictly by the numbers, there's no denying that it was an incredibly bloody conflict. North Vietnamese military forces suffered over 1 million casualties, South Vietnam lost over 200,000, and U.S. casualties numbered just under 60,000. But perhaps the more shocking statistic is that of the civilian casualties, which amount to somewhere around 2 million.

Perhaps the most egregious example of civilian casualties can be found in the disturbing first-hand accounts of the My Lai Massacre, during which U.S. soldiers killed up to 500 civilians in March 1968. American military units received faulty intelligence that Viet Cong troops were in the My Lai region and that citizens had already evacuated. They were given free reign to fire on anyone they found, and they did. Women, children, and elders were rounded up and killed, civilians were herded into large groups and executed en masse, and buildings and farms were burned to the ground.

Even worse, however, is the fact that the My Lai Massacre wasn't an anomaly. In fact, the U.S. military was actually enacting something called Operation Speedy Express, a desperate attempt started in late 1968 to pacify the entirety of the Mekong Delta. Nearly 11,000 Vietnamese people were killed, with further statistics implying that a fair few of those casualties were civilians. Reports likened Speedy Express to "a My Lay each month for over a year" (via The Nation) and described farmers being shot in their fields, as villages were destroyed by airstrikes.

The pressure of a 'body count'

The number of civilian casualties during the Vietnam War are staggering, and the stories of how those civilians were killed in regions like My Lai are nothing less than brutal. But one of the worst parts with those civilian casualties can be summed up in two words: body count.

In the midst of the Vietnam War, officials in the U.S. military decided to institute a policy that was widely referred to by soldiers as a body count. In effect, it prioritized killing as many Vietnamese people as possible, depending on it as a metric to measure success. In practice, that ultimately meant that statistics were all that mattered, and soldiers have since reported on the mindset that they were inundated by on the battlefield: "For all enlisted people, that was the mentality ... Get the body count. Get the body count. Get the body count. It was prevalent everywhere" (via The Nation). They would do almost anything to get those numbers, even hovering over fields and waiting for terrified civilians to run in fear — enough justification for them to shoot — or forcing civilians to walk in front of them in minefields. They even tried to hide those civilian casualties, claiming they were actually armed militants and that their weapons had mysteriously been destroyed in the struggle.

That behavior even became a competition rather than an atrocity, complete with tallies and leaderboards, with the most lethal battalions standing to win vacation days or beer, while officers could score high-profile promotions.

Widespread dehumanization of the Vietnamese people

Racial stereotyping and wartime have unfortunately gone hand in hand throughout history, and the Vietnam War is no exception to that. In general, the idea held by leadership in the American military was that the dehumanization of the Vietnamese people en masse would be the best way to win the war. As soon as a soldier started training, they were told that the Vietnamese people weren't people at all, so any war crimes and atrocities were, in effect, justifiable. According to Nick Turse in an interview with NPR, soldiers were instructed, "Never call them Vietnamese. Call them gooks or dinks, slopes, slants, rice-eaters."

Not only that, but this particular policy didn't only have ill effects for those actually living in Vietnam. Asian American soldiers — not necessarily just Vietnamese Americans, but Asian Americans in general — were the subjects of harassment of all kinds. Their commanding officers singled them out and forced them to dress up, making them into examples of what the enemy was supposed to look like. Racial slurs were thrown in their direction, and physical threats weren't unheard of either, with one former soldier saying he'd woken up with a bayonet at his throat. Some soldiers were even denied medical treatment, their peers believing them to be the enemy and evacuating them last from the battlefield, while female nurses were regularly mistaken for Vietnamese sex workers. All of that despite growing up in the U.S. and fully identifying as American — suddenly, that just didn't matter any more.

The fallout of government cover ups

During the Vietnam War, the picture that the American people were given by government officials was vastly different than it's understood today. The version fed to the public was essentially that Vietnam was a vitally important piece of international politics, a domino that would allow the Soviet Union to expand its influence throughout Asia if it fell to communism. The U.S. had supposedly entered the war in response to an unprovoked attack by North Vietnamese forces in the Gulf of Tonkin, and American forces were crushing the flagging Viet Cong soldiers.

In reality, though, the exact opposite was true. Vietnam was far from a strategic position, the Soviets had little interest in Southeast Asia, the Gulf of Tonkin incident didn't really happen as reported (it was actually incited by clandestine American interference in the region), and American and North Vietnamese troops were locked in a stalemate, at best. All of that information was kept secret from the public, covered up by blatant lies, until Daniel Ellsberg leaked everything to the public in 1971, publishing the true story in documents now known as the Pentagon Papers.

The American people at the time felt betrayed, but those cover ups went so far as to change the mentality of the entire nation. Until that point, the American public tended to trust their leaders and almost universally felt pride in their national identity. Afterwards, though, people adopted the views that you're likely to hear today — cynicism regarding the government, and the widespread assumption that politicians are liars.

A secret war in a neutral nation

The country of Laos was in a rather complicated position during the Vietnam War. Earlier on in the Cold War, it was viewed as a vital piece of keeping communist forces at bay in Southeast Asia, due to its proximity to China, and as the Vietnam War approached, American interest grew due to the existence of communist supply routes through the country and into Vietnam. Communist forces were indeed on the rise in Laos, but in 1962, 14 nations (including the U.S.) signed a treaty that recognized Laos as a neutral nation.

That didn't stop the U.S. from interfering in Lao politics, hence the waging of a secret war. The CIA covertly trained and outfitted anticommunist forces in Laos to fight against the Viet Cong-aligned Pathet Lao, and on the less covert front, the U.S. military took to bombing supply lines on the Ho Chi Minh Trail starting in 1964. It's estimated that planes would drop their entire supply of cluster bombs every eight minutes, and that carried on constantly over the course of the following nine years.

By the mid-1970s, over 2 million tons of bombs had been dropped on the country, killing a full tenth of the population and leaving a quarter as refugees; to this day, no other nation has seen the same level of bombing as Laos did. What's more, an estimated 80 million bombs didn't explode on impact, and 20,000 more people have died to them in the years since.

Soldiers were deliberately left for dead

In 1961, the CIA started up a secret operation intended to sabotage North Vietnamese operations. Called Oplan 34-A, the mission recruited and trained Vietnamese commandos and saboteurs to infiltrate North Vietnam — the country many of them had fled from. The mission lasted for about three years, at which point official documentation stated that there were 200 agents who had gone missing, many of whom were known to be alive and imprisoned.

That's where the twisted part of the story comes in. In late 1965, military officials arbitrarily started to declare those agents as dead, quite literally crossing their names off of the list, a few every month, until they were all assumed to have been killed in action. All of that despite the knowledge that those agents were very much alive. The reasons hardly make that look any better; the agents were left for dead simply because it was cheaper, for the most part. Those assumed dead couldn't be paid, and the funds could be redirected to other operations instead. Not only that, but the act allowed the U.S. to wash their hands of the whole operation and pretend to move on, trying to avoid culpability for the failure.

This whole secret operation was completely unknown to the public until the mid-1990s, at which point surviving agents, who had spent nearly two decades tortured in prison, faced an uphill legal battle for their back pay — a battle that their lawyers said wouldn't even exist if the commandos were American rather than Vietnamese.

The futility of the Christmas bombings

In late 1972, by trying to bring an end to the Vietnam War, Richard Nixon ordered one of the questionable events of his presidency: Operation Linebacker II, now known colloquially as "the Christmas bombings." In short, American aircraft dropped 20,000 tons of bombs over a week and half in late December (with a break on Christmas Day, hence the name). 1,600 Vietnamese people were killed, as were 33 American airmen, all to accomplish Nixon's goal of forcing the North Vietnamese government back to the negotiating table for peace talks.

Where Operation Linebacker II really looks bad is in its confusing legacy. The U.S. boasted that it had accomplished Nixon's goal — and thus led to the end of American involvement in the Vietnam War — but experts have since rebuffed that. The North Vietnamese government was running out of supplies and couldn't have sustained a war for much longer; at worst, they were probably ready to resume peace talks shortly. Some experts even believe that North Vietnamese officials had already decided to resume peace talks, but their message didn't reach the U.S. before the bombings began. Peace could've been had without bloodshed, had Nixon just waited.

What's more, the reality was that Operation Linebacker II didn't achieve peace. It did pull U.S. forces out of Vietnam, but South Vietnam still fell three years later. All the bombings really did was give the North Vietnamese people a rallying point around their own heroism, the resistance they displayed against horrific bombings.

Veterans question why they were even fighting

Time can lend a lot of perspective, and that's proven true regarding American veterans of the Vietnam War. In the decades since, thousands of them have managed to find peace by returning to Vietnam, with some moving there permanently, building new lives for themselves and feeling more respected there than they ever did in the U.S. Despite being trained to hate the Vietnamese and relentlessly fight communists, they've found peace, love, and redemption in a country that long symbolized war for them.

That association with Vietnam and beauty isn't necessarily a new discovery for all of them. One soldier recalled being deployed there during the war and falling in love with the country and its people; he couldn't understand what there was to hate about people who just wanted to farm and raise families. Photos (via TIME) showcase a similar sense of humanity amidst a brutal war: American GIs have been photographed rescuing Vietnamese children from warzones, or even cradling the head of an injured Viet Cong soldier.

None of that is bad, of course, but it paints the entire conflict in a far worse light. American veterans question why they were ever fighting in the first place and what the U.S. government found so threatening. Even in trying to find those answers for themselves, they've instead found the war to be more and more pointless, perpetuated by so many lies that one veteran even admitted, "If I were Vietnamese, I would have fought with the Vietcong" (via BBC).