Famous People Who Couldn't Stand JFK

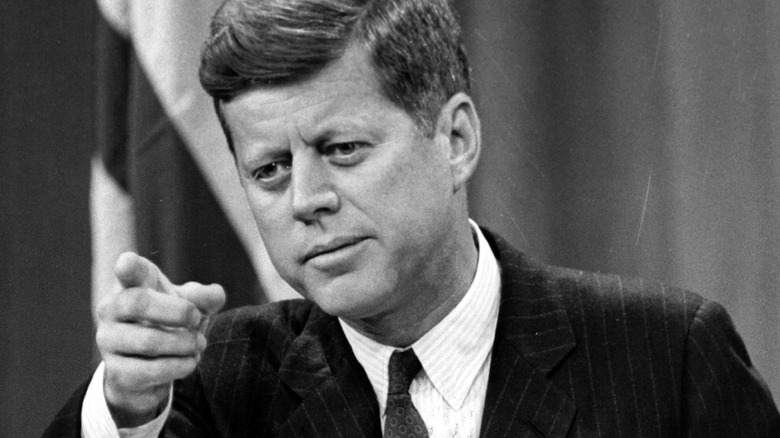

The tragedy of his death and the promise embedded in the Camelot mystique of his administration have helped keep John F. Kennedy's reputation alive. Even after revelations about his scandalous sexual behavior and hidden health issues, American citizens have given Kennedy generous approval ratings. Many historians still place him among the best presidents in American history.

But the Kennedy image is not unassailable. He's always had critics and detractors on the political right, but as his time in office fades further into history, there have been more critical appraisals from the left and center as well. Let us not forget, however, that Kennedy was far from universally beloved in his lifetime. Pop culture remembers his easy charm contrasting with Richard Nixon's apparent unease during their televised debate, but the 1960 presidential election was fiercely contested and came down to 0.2 percent of the vote. Some on the left were disappointed with Kennedy's record while it was still being written. And there was a long list of prominent figures in American, and international circles, who for one reason or another didn't care much for John Kennedy.

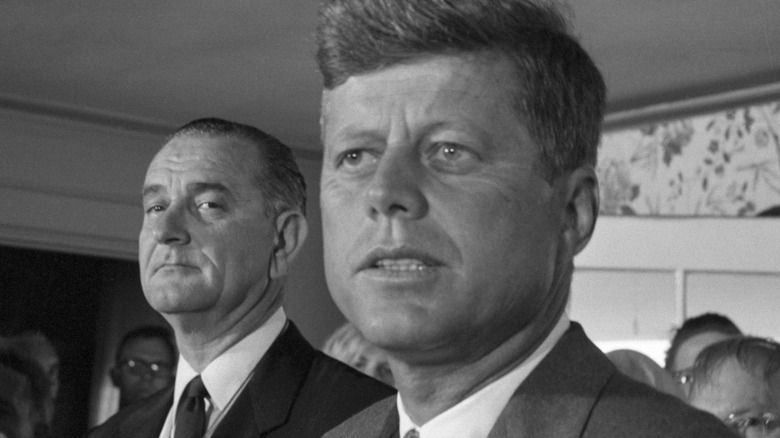

LBJ did not like JFK

As close as their race for the presidency became, John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon maintained a cordial relationship before and after 1960. The same cannot be said, at least not wholly, of Kennedy's relationship with the man he had by his side in that election. That Lyndon B. Johnson clashed with Kennedy's brother is no secret. Tensions between them flared early in the administration, and Robert F. Kennedy was not shy about assuming the mantle of his brother's chief lieutenant that might have otherwise gone to Johnson as vice president. John's death only furthered the gulf between them.

John himself wasn't exactly a fast friend to his vice president. Jacqueline Kennedy maintained a pleasant personal relationship with the Johnsons, but she claimed that her husband couldn't get a real contribution to the administration out of Johnson and doubted his fitness to be president. Kennedy deliberately marginalized Johnson and sought to drop him from the 1964 ticket. On Johnson's part, some have reported him as being an ambitious and insensitive climber who chafed at being Kennedy's vice president.

Others have claimed that Johnson found the Kennedy brothers to be hurtful coastal snobs. His grievances on that score were most directly aimed at Robert, but Johnson also seemed to resent living in Kennedy's shadow even after Kennedy's assassination and Johnson's own time in power. A chorus of "Kennedy wouldn't have done that" type complaints followed Johnson the rest of his life, and he was recorded grousing about it in retirement.

Sam Giancana felt betrayed by the Kennedys

In the minds of some biographers, investigators, and conspiracy theorists, the Mafia lurks around all corners of the Kennedy family story. Plenty of people believe that Joseph Kennedy Sr. made his millions bootlegging alongside mobsters, and Frank Costello loved to claim Kennedy as one of his partners. That the evidence for these claims is thin hasn't stopped the stories, nor has a lack of proof dissuaded some from believing that the Mafia's Chicago Outfit stole Illinois, and therefore the 1960 election, for John F. Kennedy as part of a deal with his father.

Unfortunately, some in the Mafia seem to believe that they did win the White House for Kennedy and were appalled when he sent Robert F. Kennedy gunning after organized crime. That resentment, and the heat Robert brought upon the Mafia, lies behind the conspiracy theory that the Mafia was behind the president's assassination. The mob bosses supposedly behind the assassination were Carlos Marcello of New Orleans and Santo Trafficante Jr of Florida. But another, more notorious name in organized crime has also been mentioned: Chicago Outfit boss Sam "Momo" Giancana, a jet-setting, politicking womanizer who allegedly shared a mistress with the president, Judith Campbell Exner.

Exner later claimed that Giancana boasted about getting Kennedy into the White House. His family perpetuated the myth of the Mob swinging Illinois for the Democrats, and Giancana was allegedly just as angry as Trafficante and Marcello over Kennedy's choice of attorney general. One associate even claimed (without corroborating evidence) that Giancana confessed to arranging the president's assassination.

J. Edgar Hoover despised his nominal boss

For almost 50 years, J. Edgar Hoover maintained his control over the FBI. In that time, he saw eight presidents come and go. Some of them, he liked; others, like John F. Kennedy, he didn't. Though Hoover and Joseph Kennedy Sr. shared a mutual respect, that didn't stop Hoover from compiling a file on the elder Kennedy. He took the same approach to the Kennedy son, collecting dirt on John's extramarital affairs as early as 1942. When Kennedy came into the presidency, Hoover was suspicious and scornful about Kennedy's liaisons and harbored doubts about his politics.

The bad blood between Hoover and the Kennedys was mutual. Kennedy maintained a public show of respect toward Hoover, but he neither liked nor trusted him. Hoover's near-total control over the FBI worried Kennedy, as did the agency's surveillance network. Kennedy reportedly wanted to dismiss Hoover as director of the FBI, but he announced that he would keep Hoover on the day after his victory in the 1960 election was announced. A contributing factor was likely Hoover's knowledge of Kennedy's private scandals — something he made plain to Kennedy and his attorney general brother.

Kennedy got a measure of petty revenge by barging in on a napping Hoover or taking him out to uncouth diners for lunch. As with so many executive branch hostilities involving the Kennedys from those years, the real tension was between Hoover and Robert F. Kennedy, who feared Hoover's power, opposed it where he could, and resented his intrigues.

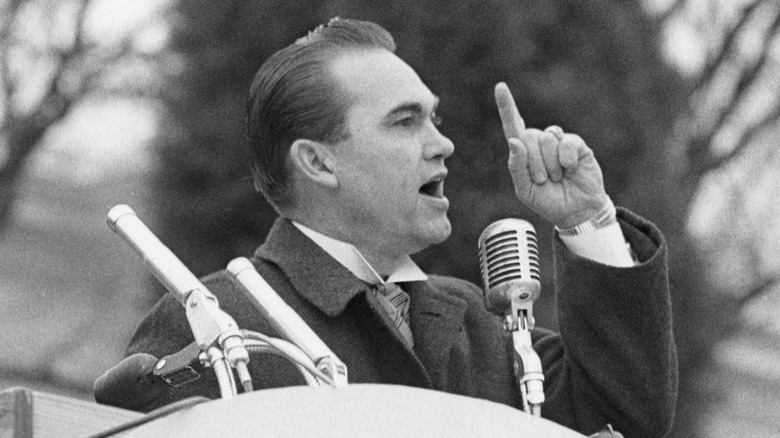

George Wallace fought Kennedy on segregation

The 1960s was hardly free of political strife, but the extreme polarization between Democrats and Republicans we see in the 21st century was not there at the time. The parties were big tents with considerable ideological differences among their various groups, meaning that the character and priorities of the president were much more important in shaping an agenda. It also meant that a president like John F. Kennedy could attract significant opposition and animosity from within the ranks of his own party — from the "Dixiecrats," those southern Democrats who were hostile to Kennedy's steps toward civil rights action.

Among those Dixiecrats was George Wallace, of "segregation forever" infamy. Wallace always maintained a personal affection for Kennedy, and was also an early Kennedy supporter in the 1950s. But by 1963, as Alabama's governor, Wallace personified Southern resistance to integration. His intransigence over admitting Black students to the University of Alabama went as far as threatening to defy federal court orders and raising the specter of riots. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy became personally involved in the ultimately successful effort to get Black students into the school without having to arrest Wallace and potentially set off violence and chaos in the South.

Kennedy followed up his brother's work with a speech to the nation, proclaiming his intent for a civil rights bill. Wallace maintained his opposition to civil rights into the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson, who summoned Wallace for a talking-to ahead of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Strom Thurmond resisted Kennedy's civil rights program

As hostile as George Wallace was to the civil rights agenda advocated by John F. Kennedy, he still maintained a fondness for Kennedy as a person. His harshest comments were about Robert Kennedy, and he ultimately swallowed, however begrudgingly, the integration of the University of Alabama without getting himself arrested. But he wasn't the only Dixiecrat to come into conflict with Kennedy over civil rights.

Strom Thurmond has achieved a measure of infamy in American history for throwing a 24-hour-plus filibuster during the passage of the 1957 Civil Rights Act. He had little to say about race when he was a moderate-to-progressive governor of South Carolina in the 1940s, but by the time he reached the Senate, he was a full-throated racist. He was as opposed to the civil rights bill Kennedy proposed after the standoff with Wallace as he'd been to the one in 1957, and Thurmond had additional bones to pick with Kennedy. His claims that Kennedy was planning to surrender the U.S. nuclear arsenal to the United Nations was such an outrageous conspiracy theory that neighboring state newspapers with circulation in South Carolina went after him.

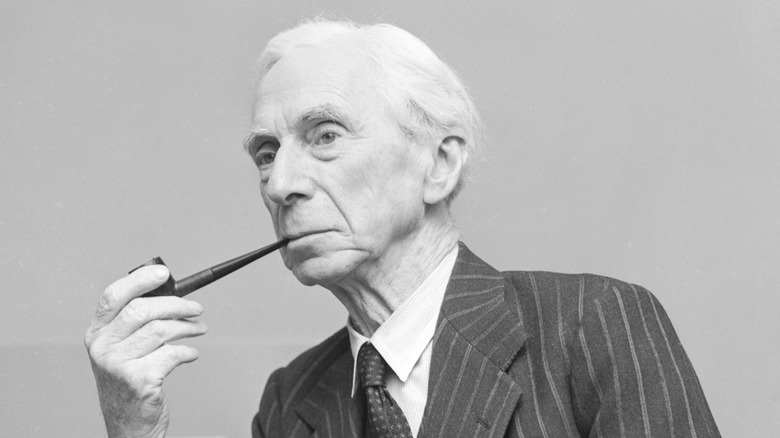

Bertrand Russell attacked Kennedy from the left

Dixiecrats came at John F. Kennedy from the right, but Bertrand Russell, not a politician or an American, nevertheless was among the most prominent critics of Kennedy from the left. Russell was a pacifist and an avowed opponent of nuclear weapons. He was so opposed to the thought of nuclear weapons that, as the Cold War began, he declared, "I am for controlled nuclear disarmament, but if the Communists cannot be induced to agree to it, then I am for unilateral nuclear disarmament even if it means the horrors of Communist domination" (via RAND). For refusing to consider unilateral disarmament, Russell branded Kennedy, among other Western leaders, as "much more wicked than Hitler ... they are the wickedest people who ever lived in the history of man and it is our duty to do what we can against them."

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, Russell sent telegrams to both Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev. Notably, Russell did not criticize Russian policy regarding Cuba in his message to Khrushchev, but did reprimand Kennedy for America's blockade. Russell rushed Khrushchev's conciliatory reply to Kennedy, who did not appreciate Russell's involving himself in an international crisis. When the crisis passed, Russell did express regret for not taking a gentler tone with Kennedy. And after Kennedy's assassination, Russell weighed in, criticizing the Warren Commission's composition and the handling of evidence.

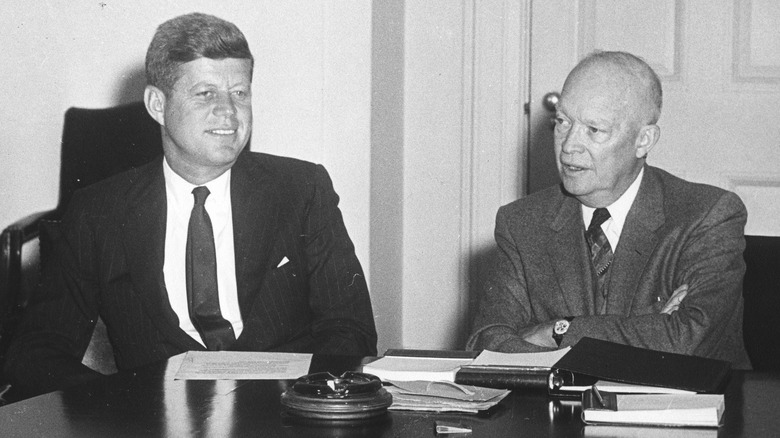

Dwight Eisenhower doubted and resented Kennedy

"I like Ike" made for a good campaign slogan, and for plenty of Americans, it was more than a rhyme. But John F. Kennedy did not wholly like Dwight D. Eisenhower, and the feeling was mutual. The age difference between them — 27 years — didn't keep them estranged so much as a clash of personality, at least on Kennedy's part. According to Timothy J. Naftali in his lecture "The Peacock and the Bald Eagle: The Remarkable Relationship Between JFK and Eisenhower" (via The Chautauquan Daily), a Kennedy biographer was quoted as saying that the younger president found Eisenhower cold.

For Eisenhower's part, he was apparently bothered by Kennedy's relative youth coming into the most powerful office in the world, and by his inexperience. He also disagreed with nearly every major decision Kennedy made as president. Ironically, Eisenhower's lack of confidence in his successor helped reinforce his determination not to undermine Kennedy publicly, and to offer support and advice where and when he could. Eisenhower was among those Kennedy consulted during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

But Eisenhower developed an additional grievance with Kennedy after the latter's death. Per Geoffrey Perret's "Eisenhower," the general saw a poll floated to American historians two years after Kennedy's assassination as an attempt to cement Kennedy as a seminal figure in American history. He was dismissive of what he called the "Kennedy cult" that heaped praise upon Kennedy — and was hurt by his own ranking in the poll towards the bottom of the list.

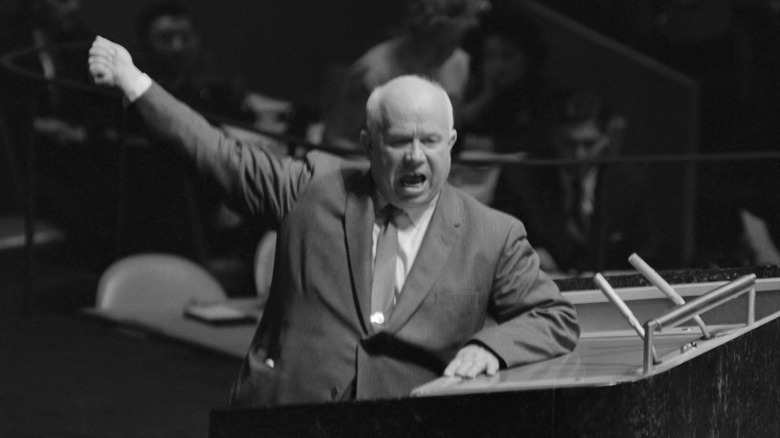

Khrushchev thought Kennedy was green

"[I] liked and respected [John] Kennedy." So said Nikita Khrushchev (per Michael Kort's biography "Nikita Khrushchev"), and so he maintained throughout his life and career. He was impressed by then-Senator Kennedy when the two briefly met in 1959, and he preferred Kennedy as a Cold War adversary over Richard Nixon. But when it came time for the two to have their first and only meeting as leaders of rival nations, Khrushchev assumed that the younger, less experience Kennedy would be a pushover.

He aimed to embarrass America during their Vienna summit, and by some estimations, he succeeded. He was cavalier in discussing nuclear weapons, pushed to bring Berlin under full East German control, and generally threw Kennedy for a loop with his brazenness. In the immediate aftermath of the meeting, Khrushchev allegedly boasted that the U.S. president was spineless and incapable of facing a Soviet challenge. For his part, Kennedy readily conceded to his aides and even to the American press (anonymously) that he'd been thoroughly razed.

One might have expected Khrushchev to crow about dominating a sitting president at a summit. But when it came time to write his memoir, "Khrushchev Remembers," the Soviet premier glossed over this encounter, preferring to echo his claimed fondness for Kennedy and his preference for Kennedy over Nixon or Dwight Eisenhower. He called Kennedy's death "a great loss" that damaged U.S./Soviet relations.