The Bizarre True Story Of The Heist After Muhammad Ali's Comeback Fight

Muhammad Ali's 1970 comeback fight in Atlanta, Georgia was notable both in and out of the ring. Having changed his name from Cassius Clay — which he described as his "slave name" — and converted to Islam, the boxer and 1964 world champion showed his willingness to stand by his societal, religious, and political principles. This culminated in 1967, when he refused to be enlisted into the U.S. Army to fight in the Vietnam War.

Though he claimed to be a conscientious objector, Ali was convicted of being a draft dodger and blacklisted from competing in most U.S. states. Georgia was chosen as one of the few states Ali could fight in, and despite having been out of the professional sport for three years, the former champ defeated opponent Jerry Quarry by technical knockout in just three rounds. Though not a classic win like 1974's "Rumble in the Jungle," it is considered a landmark fight in his career.

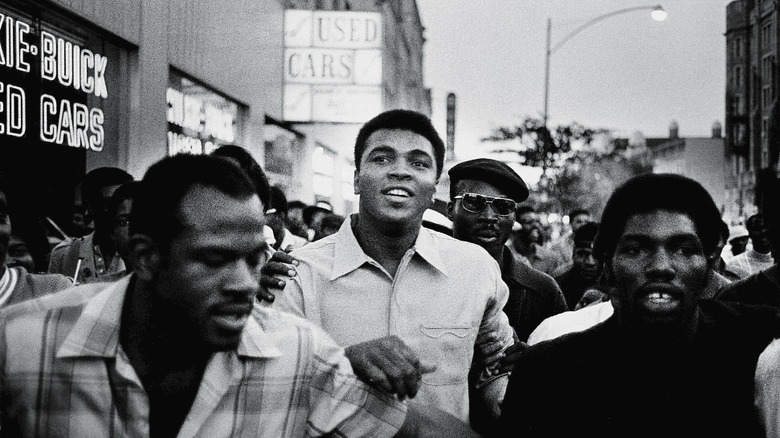

But what's really getting people's attention nowadays is the story of the audacious crime that happened afterward. The fight took place on October 26, and while Ali and his friends, family, and supporters celebrated his victory, hundreds of people, many of whom were in town especially for the fight, became victims to one of the most coldly calculated robberies of the era.

Ali's comeback was a major draw

Muhammad Ali's decision to forgo service in the U.S. Army for political and religious reasons didn't sit well with officials of the U.S. government (with which he became locked in a bitter legal battle) or the sport of boxing. In some corners of the country, Ali was despised. But many of the boxer's fans agreed that the bloody Vietnam War was a mistake, and with them his star only rose higher.

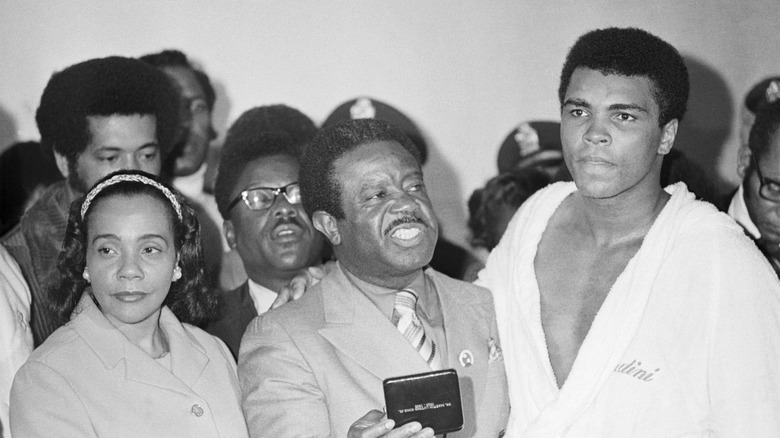

His 1970 comeback fight was organized through promoter Robert Kassel, whose father-in-law, Harry Pett, was a friend of Georgia's first Black senator since Reconstruction, LeRoy Johnson. Pett convinced the senator to exert his political influence to grant Ali a boxing license. Ali's opponent, Jerry Quarry, was billed as "The Great White Hope" by some outlets, highlighting the racial tension that underpinned both the bout and the Southern states of America at the time.

Thousands of fans from nearby cities took the opportunity to show their support for both Ali and the politics he represented by streaming into Atlanta for the fight. High-profile Black celebrities like Diana Ross and Sidney Poitier were among them. "It was the greatest collection of black money and black power ever assembled until that time," historian Bert Sugar told Atlanta Magazine. And for that reason it also drew the attention of criminals looking to make a quick score from those thousands of fans who had shelled out as much as $100 a ticket — around $810 in today's money — to see Ali's return.

A birthday bash with underhand motivations

The Ali-Quarry fight took place at the pristine Municipal Auditorium, a stunning venue suited to a once-in-a-lifetime event. The fight was as prestigious to Muhammad Ali fans as it was controversial to his critics. Fans from all backgrounds, from VIP celebrities to everyday people to criminals and hustlers, showed up for the occasion in all their finery. Unfortunately, this made them marks in the aftermath of the bout.

In the run up to the fight, many ticket holders received flyers advertising a free birthday party hosted by "Fireball" for a man named "Tobe" at 2819 Handy Drive in Collier Heights. While the VIPs mingled at the luxurious Hyatt Regency hotel after Ali's first win in three years, countless others headed to Handy Drive, where they hoped to continue the rapturous atmosphere of the win that represented so much to so many. But the night took a darker turn.

Guests walked into a masked heist

Hundreds of partiers high on adrenaline from the thrill of Muhammad Ali's comeback victory streamed into Handy Drive on the night of October 26. But as they entered through the door of the home where they expected to find a raucous occasion, they were instead met with three ski-masked men armed with guns, including a shotgun. What happened next was downright bizarre.

As guests filed in and saw the reality of what they had walked into, they were ushered into the property's basement, where they were stripped of their valuables and clothes. Many, of course, were wearing the finest outfits they could afford for the occasion. Others carried wads of cash for the party that was to feature casino games such as craps.

Few of the victims filed complaints with the police, possibly out of embarrassment, or perhaps due to the underlying distrust of law enforcement at the time. After all, the heist took place after the height of the civil rights movement, when police brutality and unequal policing were hot button topics, as they are today. Those who did, however, saw the case taken on by J.D. Hudson, a respected Black detective. And his connections in Atlanta helped him clear the fog around the strange night after Ali's win.

The investigation took many turns

J.D. Hudson's links to the events of October 26, 1970 begin with the comeback fight itself. To begin with, he (pictured) was assigned the task of being Muhammad Ali's personal security guard during the former champion's time in Atlanta. To that point, it was the honor of Hudson's career. But when the police got wind of the scale of the robbery at Handy Drive, he found himself with an intriguing new assignment.

The audacious heisters were reported to have walked away with around $100,000 in contemporary news reports, but today the number is said to have been around $1 million. Hudson's first step in discovering who was behind the operation was locating the owner of the house, who turned out to be a man named Gordon "Chicken Man" Williams. Williams was a local hustler, and once his name was leaked to the public in the aftermath of the robbery, a rumor suggested he had been shot to death by angry victims.

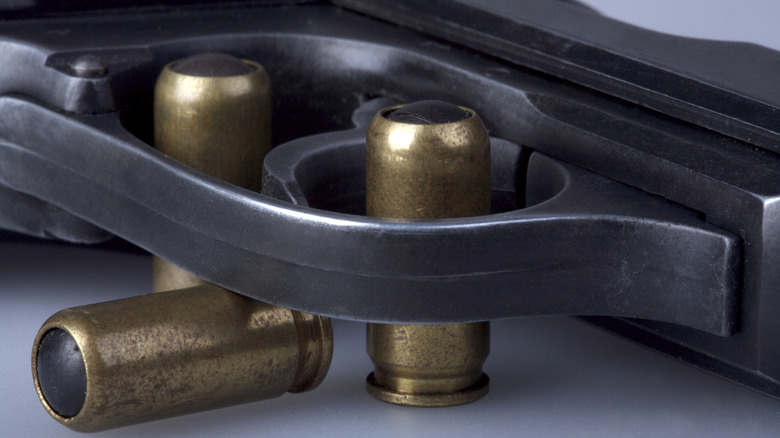

However, the truth was that Williams had simply loaned the house, which he owned, to "Fireball." In fact, the robbers kept Williams' girlfriend hostage to implore their victims not to escape. But when investigators eventually discovered a discarded shotgun in a bag near the house, they finally had a solid lead.

The victims got their revenge

The story of Gordon "Chicken Man" Williams' death at the hands of those he had robbed was a myth (which, when it comes to famous crimes, is pretty common). But months later, when it looked as though the robbers were due to face justice, the rumor came to uncannily echo the bloody fallout of the heist. The owner of the gun was a man named Houston Hammonds, who under pressure provided two names — people he claimed to have bought the firearm for. One was James Hall, though it later emerged his real name was James Ebo. Following J.D. Hudson's investigation, he was indicted along with James H. Jackson.

Hudson had warned that it was a race against time for the police to identify and arrest those responsible for the crime — those they had robbed would no doubt take the task into their own hands. Sure enough, it was reported in May 1971 that Ebo and Jackson — who had been indicted under their aliases McKinley Rogers and James Henry Hall — had been shot and killed by 11 bullets as they sat in a stolen Cadillac in the Bronx. A third man, Donald Phillips, was also killed in the car. "It appears the victims got there first," Hudson told The New York Times.