Things About 9/11 That Still Don't Make Sense

"Where were you on 9/11?" That's one of those questions that's not liable to go away anytime soon, and for good reason. The September 11 attacks played no small part in changing the world as we know it, whether that be in terms of airport security and the TSA regulations that have become an intrinsic part of every flight, or in the wider sense of foreign relations and fears that people might hold when it comes to public safety. Even fields that might not seem related on the surface have been touched by the effects of 9/11, ranging from medical research to domestic policy. Much has been written about September 11 and the ways it affected people around the globe, both in the short term as well as the long term.

However, that's not to say that the public knows everything about the events of that day, nor does anyone understand exactly what may become of its far-reaching effects. For that matter, two decades have passed as of the writing of this article, and even the official cases regarding the plans behind 9/11 are still heavily debated, especially as some of the accused still haven't stood trial.

All of that to say: Despite the indelible mark 9/11 has left on history, there are still quite a few things that don't entirely make sense, or just seem strange. Here are a handful of them.

Airport security was incredibly lax prior to 9/11

Nowadays, TSA regulations and that long security line at the airport are just an intrinsic part of getting onto a plane. That general process is something that came about largely due to 9/11. After all, airline security was so lax back in 2001 that the hijackers were able to exploit the system with little effort. No one needed an ID or boarding pass, knives were allowed on flights, and the only layer of protection offered was a simple metal detector. Airline security expert Jeff Price put it succinctly: "It was so easy — a lot of us were surprised it hadn't happened sooner" (via NPR).

But then, if experts were surprised a hijacking on the scale of 9/11 hadn't happened earlier, why was airport security so lax? For that matter, it's not like 9/11 was the first-ever airline hijacking. The mystery of D.B. Cooper predates 9/11 by multiple decades, and the first hijacking dates back to 1931. Politically motivated hijackings really began in the late 1960s.

Why the loose security, then? There is actually an answer here, strange as it might seem to modern sensibilities. Both the Cooper hijacking and those of the late 1960s did prompt change, but one of the main problems airports considered was the possibility that people would be scared off by security measures. According to Price, "Security was almost invisible, and it was really designed to be that way ... something in the background that really wasn't that noticeable."

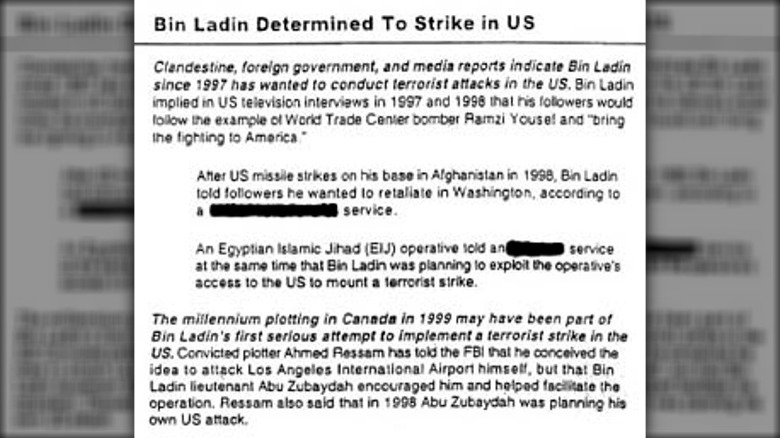

The CIA knew an attack was imminent

Given just how devastating 9/11 was, both at the time and in terms of its legacy in the years since, you'd think the attack came as a complete surprise. But that couldn't be further from the truth; the CIA saw 9/11 coming before the attack.

As early as May 2001, CIA officials were almost certain that an attack on U.S. soil was imminent, even if they weren't sure of the particulars. All they knew was that the signs were there: a calm before the storm as known terrorists went into hiding in preparation. They drew up plans to make a preemptive strike against al-Qaida, only for that plan to be shot down, and in July, they received intelligence that confirmed an attack was on the horizon. Rushing to the White House, they emphasized that something had to be done. But once again, those warnings fell on deaf ears, as did their most famous warning on August 6: "Bin Laden Determined to Strike in U.S."

How could those warnings have been ignored? The CIA officials involved don't even know. They've suspected that the Bush administration was both too cautious (not wanting to let al-Qaida know they suspected anything) and simply ignorant, thinking of the threat like it was a war rather than terrorism. According to members of the Bush administration, they genuinely didn't remember those warnings; the CIA's alerts had become noise, and they believed they were doing everything they needed to.

Bureaucratic mismanagement when it came to counterterrorism

The CIA knew months in advance that al-Qaida planned to launch a strike of some kind on American soil, and other intelligence departments weren't necessarily slacking either. Everyone was doing their part when it came to gathering intelligence, so why were they also completely unprepared when the attack finally came?

As it turns out, there is technically an answer to this question, but that answer is essentially just an almost unbelievable level of mismanagement and miscommunication. In short, different government agencies just didn't talk to each other, and they all had vastly different goals. The CIA was largely focused on overseas targets, while the FBI was far more concerned with tracking domestic issues. In other words, the CIA, for the most part, wasn't looking at what potential terrorists were doing once they were within U.S. borders, while the FBI didn't have a viable way of determining just how much of a threat foreign groups were to the American homeland. And while that seems like a problem that could be easily fixed by a bit of communication, there was no central group to set larger priorities and plans for all American intelligence on the whole. Collaboration just wasn't the norm, which left major law enforcement and intelligence agencies with huge gaps in their knowledge.

U.S. law enforcement allowed terrorism to grow

There are more than a few ways in which American law enforcement and intelligence found they were ill-fitted to stop 9/11 as the result of poor organizational structure or miscommunication. However, the problem wasn't just where foreign intelligence — and its application to the U.S. mainland — was involved. Domestically, government agencies didn't seem concerned about the problems growing right in front of them — which, especially with the power of hindsight, is almost unimaginable.

Prior to 9/11, radical cells were given nearly free rein to grow and thrive within the borders of the U.S. They were allowed to fundraise and spread their beliefs effectively uninhibited, even though laws existed before the attacks which would have allowed law enforcement to shut down those radical groups. That law was simply not enforced, often because prosecutors thought that working such cases was more work than it was worth — all despite knowing that taking out smaller terrorist cells was an important step in fighting against the larger groups.

Not only that, but reports written decades before 9/11 also revealed that the U.S. was generally ill-equipped to deal with attacks carried out within its borders. Those reports acknowledged that the U.S. had no domestic system to combat the threats of terrorism and that, as things stood, terrorist cells were likely to succeed in whatever they wanted to do. And yet little policy was enacted to address that problem, and what was codified was often ignored.

The intended target of the fourth plane

When people think of 9/11, the image that most likely comes to mind is that of the World Trade Center in New York — the infamous sight of the towers on fire before their collapse. However, the Twin Towers and the Pentagon were both targeted on 9/11. And there's also Flight 93, the plane that went down in a field in Pennsylvania.

As the reports say, the plane left Newark, New Jersey, for San Francisco, California, and just before 10:00 a.m., the hijackers turned the plane back toward Washington, D.C. Unlike with the other three planes, the passengers of Flight 93 had heard about the other attacks, and they formulated a plan: storming the cockpit to try and retake control of the plane. They did exactly that, but the hijackers' backup plan was always to crash, even if they couldn't reach their destination; just 10 minutes after the hijacking, the plane hit the ground, killing everyone on board.

But the fact that Flight 93 never reached its intended target has naturally left people wondering: Where was it meant to go? Investigations concluded that an attack on the U.S. Capitol building was the most likely goal, and one of the conspirators later stated that to be true. Which seems like a rather straightforward answer, though it's also interesting to note that Osama bin Laden actually wanted to attack the White House, not the Capitol building, but was overruled by his co-conspirators.

[Featured image by MomentsByCarol via Wikimedia Commons | Scaled and mirrored | CC BY-SA 4.0]

First responders and cognitive conditions

As the years have passed, there's been a fair bit of discussion regarding the long-term health of first responders who were present at or inside the World Trade Center on 9/11 — especially those who spent lengthy spans of time there in the aftermath. Cancers, respiratory diseases, and PTSD have been reported and studied in many cases, but in more recent times, there's been another apparent consequence of exposure to the debris.

Namely, degenerative cognitive conditions have become increasingly common in 9/11 first responders, though the symptoms weren't immediately obvious, taking about a decade and a half to really manifest with varying degrees of severity. For some, that means overall issues with memory, but for others, it means severe cases of dementia. Specialists have weighed in, explaining that many of the first responders are now in their 50s, but their brains resemble those of individuals who are decades older, and they've been diagnosed with conditions that normally aren't seen until people are in their 70s. Something like that, especially on such a large scale, is practically unheard of.

And medical professionals aren't exactly sure what to make of it. A Stony Brook University-led study run from 2014 to 2023 demonstrated a definite correlation between exposure to toxic dust at the World Trade Center and a not-insignificant percentage of patients developing dementia over the course of the study itself. That said, it's only a start. Researchers still don't know the extent of those diseases and are planning for further research.

Torture carried out at Guantanamo Bay

When it comes to the brutalities of global conflict, anyone would want to hope that their own country isn't capable of turning toward barbarism. But in the aftermath of 9/11, American intelligence showed its dark side and engaged in levels of torture that people have openly admitted they can barely believe.

Records have made reference to the CIA's secret prisons and chilling details of Guantanamo Bay, where officials used all sorts of methods of torture on individuals accused (but not necessarily guilty) of being complicit in the September 11 attacks. There are multiple reports of waterboarding, sleep deprivation, physical abuse, and even threats of rape, without getting into the grisly details. Those subjected to that torture have, in some cases, developed PTSD, and one even died.

All that ultimately did was muddy a lot of waters, though. For one, torture has been shown not to be effective in interrogation, casting doubts on any information gathered at Guantanamo Bay. On top of that, everything that happened at Guantanamo Bay was a human rights violation under the Geneva Conventions, which the Bush administration skirted by declaring the prisoners "unlawful enemy combatants." The U.S.'s use of torture left a stain on the country's reputation that affects foreign relations, but the prison has remained fully operational. Despite outcry and controversy, international organizations don't really have the power to enforce human rights laws, and nothing has been done to change that status quo, allowing the CIA to avoid any consequences for its actions.

The accused still haven't gone to trial

As of this writing, well over two decades have passed since 9/11, and you'd think the attack's infamy would be a reason to see the accused brought to justice quickly. As it turns out, though, the opposite has proven true. In fact, five men were handed charges related to their part in planning the 9/11 attacks; they were all captured in 2002 and 2003, and their cases have basically been in limbo ever since.

For one, the torture endured by those men during their detention in Guantanamo Bay has forced lawyers to reconsider whether anything said during that time can be fairly treated as real evidence. That process on its own has taken a long time. Then, President Barack Obama tried to bring them to justice, announcing in 2009 that one of the trials would be taken to a federal court in New York — an idea that New York City ultimately refused to allow, citing the high cost of security. A short while later, the announcement suddenly came that the terrorists would face a military tribunal — an idea that's been controversial at best. And then things just stalled.

A judge announced that jury selections would begin in early 2021, only for that process to be postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hearings were canceled again in 2022 as legal teams failed to solidify pretrial agreements, and things only got more complicated in 2024 as plea deals were suddenly rescinded — a confusing and convoluted failure of the justice system in the eyes of many people.

The role of Omar Al-Bayoumi

Even two decades later, it turns out there are still active mysteries about 9/11 to uncover — things that no one fully understands yet. And at the center of one of those mysteries is a man named Omar al-Bayoumi.

Al-Bayoumi is a Saudi national who has long been suspected of prior association with two of the 9/11 hijackers. Investigators were aware that al-Bayoumi had helped those two hijackers find a place to live in Southern California, and British police raided his apartment just over a week after 9/11. Ultimately, a few pieces of evidence were uncovered that seemed to imply that al-Bayoumi was probably aware of the hijackers' plans. Included was a piece of paper with mathematical equations and a sketch of a plane, a video of al-Bayoumi giving a tour of Washington, D.C. (which included shots of security points at the Capitol building), and another video of him with the hijackers at a party. All of that evidence was released to the public two decades after the attacks.

The whole situation has raised a lot of questions. Al-Bayoumi's identity is a source of debate, with some people speculating that he has ties to Saudi Intelligence, potentially as a paid informant. On a similar front, families of 9/11 victims have long speculated that Saudi government officials — possibly even members of the royal family — were complicit in, at least, financing the hijackers, though the official word is that no such tie exists.

Perpetually redacted documents

While there are still persistent mysteries about 9/11 that no one has a solid answer for, there are also the mysteries that the public in particular has been left to wonder about. And like any other case where large-scale government investigations are involved, redacted intelligence reports and secret evidence are always a source of speculation.

In the case of 9/11 specifically, it took literal decades for the FBI to release information to the public, and even when it did, a lot of those pages were heavily redacted. Requests by senators were basically ignored, leaving victims' families frustrated and confused in equal measure. Evidence acquired by British police and shared with the FBI was never given to the 9/11 Commission, which was responsible for compiling the official account of the attacks.

That left people wondering why it took so long for that information to be released to the public, why it was hidden in the first place, and why so many reports are still so heavily redacted. Some have suspected that all of that secretive behavior was due to U.S. government trying to protect its allies and possibly cover up Saudi involvement. But to make things even more confusing, the Saudi government has applauded the push to declassify those documents, claiming that they wouldn't reveal any evidence of their involvement. So the reason behind all of that secrecy is still quite the unanswered question.