The Most Brutal Deaths That Happened On The Oregon Trail

The stuff of larger-than-life legend thanks to books, history classes, and the popular computer game of the same name, the Oregon Trail was not for the weak. During its peak years of 1840 to 1860, up to 400,000 people chose to pack up their families and a few possessions to become emigrants, overlanders, and Oregon Trail pioneers. The rough road started in Independence, Missouri, and after 2,000 miles of rocky terrain and wilderness filled with all kinds of hazards, it spit them out in the Willamette Valley of northern Oregon (if they didn't veer off to California or Utah). At a rate of no more than 15 miles a day, it took the average party as long as six months to make the trek. And a great many of the people who started the trip tragically didn't finish it

Among the messed up things that actually happened on the Oregon Trail, about 10% of all travelers died along the way. Most of the dead succumbed to common diseases, infections, or injuries, while others died in strange, preventable, and ghastly ways. Here are some stories from the Oregon Trail of pioneers whose deaths were unimaginably painful, weird, disgusting, or startling.

The boy with worms in his legs

In 1846, Edwin Bryant hit the Oregon Trail. He'd attended a few classes of medical training, and the news got around his wagon train that he was the closest thing to a doctor available. As his party traveled along the Platte River in what is now Nebraska, another family sought him out to treat their boy, who Bryant estimated to be about 8 or 9 years old. While riding on a wagon tongue, the child fell off and had his leg crushed under a wheel.

When Bryant arrived at the makeshift surgical tent, he learned that the injury, poorly dressed with some cloth, had occurred nine days earlier. The parents contacted Bryant because the previous night the boy had reported that he could sense — accurately, as it turned out — what felt like worms wriggling in his leg. "It was discovered that gangrene had taken place, and the limb of the child was swarming with maggots," Bryant wrote in his journal (via End of the Oregon Trail). "The childs leg from his foot to his knee was in a state of putrefication."

Throughout history, amputation has been a brutal practice, and Bryant attempted the procedure the best that he could, using a butcher knife, a handsaw, and an awl to cut off the leg from above the knee. The boy wasn't anesthetized and didn't react to the pain of surgery whatsoever; by the time Bryant removed the leg, the boy had died.

Cholera decimated the Freel family

The 1850s were among the most active periods of emigration along the Oregon Trail. That era tragically happened to coincide with an upswing of cholera in many parts of the world. A highly contagious disease, cholera's symptoms include diarrhea and vomiting so severe that it can lead to fatal dehydration within days. Because Oregon Trail travelers tended to prepare for the journey and use water at the same sites, particularly the North Platte and Platte Rivers, cholera easily and quickly spread.

In 1852, a man named John L. Hughes received a letter from an unidentified niece, a member of the Freel party who had attempted the Oregon Trail. The writer sought to inform Hughes of how cholera had ravaged her family, and with shocking, staggering quickness. "First of all Francis Freel died June 4, 1852 and Maria Freel followed the 6th, next came Polly Casner who died the 9th and LaFayette Freel soon followed, he died the 11th, and her baby died the 17th," she wrote (via the Oregon-California Trails Association). "You see we have lost 7 persons in a few short days, all died of cholera."

Richard Harvey fell under a wagon wheel

While there are a fair few things we don't know about covered wagons, it's common knowledge that the oxen-pulled vehicle was the primary method that Oregon Trail emigrants used to haul their possessions thousands of miles westward. However, people rarely rode in wagons on the Oregon Trail; instead, travelers usually walked alongside their vehicles, but children could sit inside if they got tired. Weighing about a ton each on average, they were not only heavy but difficult to maneuver, and it was easy to lose control when traversing rocky paths or hills.

If someone got in the way of an unsecured wagon, it could result in serious injuries or a particularly grisly and painful death, as it did in 1847 for an eight-year-old child named Richard Harvey. "Mr. Harvey's young little boy Richard 8 years old went to git in the waggon and fel from the tung," reads a diary entry from Oregon Trail traveler Absolom Harden (via the Oregon-California Trails Association). "The wheals run over him and mashed his head and kil him ston dead." Harvey died instantly from injuries sustained in the accident.

John Markham was killed by his mother

In 1847, the Markham family — Samuel and Elizabeth and their five children — embarked on their Oregon Trail journey. They were only about 400 miles from the endpoint of Oregon City, near the Snake River, when on September 15, 1847, Elizabeth Markham had what today would be called a mental break. Exhausted from months of grueling travel, Elizabeth announced to husband Samuel that she could not and would not go any farther. Samuel stormed off after the ensuing argument, leaving Elizabeth alone in the wilderness. He continued on with the five Markham children and all of their possessions, only to calm down a few hours later and send the older son John to retrieve Elizabeth.

Eventually, Elizabeth Markham caught up with the rest of her family, but she was alone. Her explanation for John's absence was chilling: she claimed to have killed their son by beating him with a rock. After setting back to retrieve his son — who was fortunately still alive — Samuel returned to his wagons, only to discover that Elizabeth had set one of them on fire. In spite of the violence and property destruction, the Markhams remained together and settled in Oregon City, where they operated a store for a few years before divorcing.

Baby Susannah drank poisoned raw milk

In 1852, a couple identified in historical reports as John and Josephine Bristow left Illinois and set out on the Oregon Trail. They got as far as Fort Kearney, a stopping point near the Platte River in what's now Nebraska, before the first of two tragedies struck the family. First, Josephine died on April 6, 1852, having contracted cholera like so many others did after drinking contaminated water just three days earlier. The Bristows had taken their baby with them, a girl named Susannah, who was estimated to be aged somewhere between 9 and 15 months at the time of her mother's death.

Susannah was still in the breastfeeding phase, and rather than let his baby starve to death, he entrusted her care and feeding to a female relative in another party riding in a different wagon train. But five weeks later, Susannah was dead, and that time it may not have been the usual culprit, cholera. For one, the party that Susannah had been passed into the care of did not contract cholera, at least not when the baby died, which one would expect for such a contagious disease. Instead, another scientifically viable theory has been proposed: contaminated milk.

Fearing Susannah would spread the illness that killed her mother to a nursing surrogate, it is believed that travelers may have fed Susannah untreated cow's milk, seen as a viable emergency alternative. However, the cows from which the milk was obtained had likely been grazing on toxic plants, likely including snakeroot and poison ivy, and their toxins were fatal to the nursing baby Susannah.

The drunk driver on the river

One of the most common and worst ways to die on the Oregon Trail was accidental drowning. The path from the Midwest to the West Coast involved the crossing of numerous bodies of water, which travelers also made liberal use of for cleaning, drinking, and recreation. Even as the Trail became more sophisticated, with bridges and ferry boats springing up to make navigating and enjoying the waterways a little easier, people continued to attempt to cross rivers on their own, sometimes without even fortifying or preparing their wagons.

Historical records from 1853 discuss one such individual, who thought he could safely and quickly pass through Buffalo Creek, in what is today Colorado. Neglecting to account for a recent heavy rainfall that made the creek much more voluminous than it normally would be, and not doing anything special to his wagon, he drove the vehicle right into the water. It quickly sank along with the reportedly drunk operator, who joined the ranks of historical figures who died by drowning, albeit anonymously.

John Shotwell accidentally shot himself

Pioneers heading out west on the Oregon Trail packed for the journey with an eye toward necessity and also fearing the worst. The average covered wagon was equipped with at least a few firearms, which were useful for both hunting animals for food and as protection against potential attacks from Native Americans. The latter was an extremely rare occurrence on the Oregon Trail in the mid-1800s, but the mostly white travelers unfamiliar with the West remained anxious about the possibility.

With so many guns around, gun mishaps became common — behind only disease, accidental shooting was the biggest cause of death on the Oregon Trail. A man with the unfortunate and tragically ironic name of John Shotwell, who died in May 1841, has been identified by historians as the first gunshot fatality on the Oregon Trail. "A young man by the name of Shotwell while in the act of taking a gun out of the wagon, drew it with the muzzle towards him in such a manner that it went off and shot him near the heart," witness and pioneer John Bidwell wrote in his journal (via Roadtrippers). "He lived about an hour and died in full possession of his senses."

John Snyder got fatally stabbed during a fight

In early October 1846, the Donner Party of travelers made it to the Humboldt River and the start of the Oregon Trail-adjacent offshoot path known as the California Trail. While some members of the group continued on, a few families — Reed, Graves, and Breen among them — were so slowed down by exhaustion that they became separated from the rest due to traveling at a slower pace. On October 5, 1846, growing hostilities among some of the pioneers boiled over into a brawl that left one person dead.

John Reed grew incredibly angry when he saw that John Snyder, the hired wagon driver for the Graves family, had gotten his oxen's reins tied up with those attached to Reed's pack animals. He instigated a verbal altercation with Snyder, who responded by cracking his bullwhip at Reed's head, making contact. Reed pulled out his weapon, a hunting knife, and the two men tried to attack each other. Reed got in one final, deadly blow, stabbing Snyder in the chest, killing him instantly. The other families considered hanging Reed or holding a trial after they reached their final destination in California, but ultimately decided to banish him from the wagon train.

Joel Hembree's abdomen was crushed by two wheels

The Hembree family of McMinnville, Tennessee — Joel and Sara and their eight children — hit the Oregon Trail via the traditional point of departure at Independence, Missouri, in May 1843. About two months later, right after passing Bed Tick Creek in what is now Wyoming, the Hembree party encountered a rocky bit of terrain that violently shook its wagon. The second-youngest Hembree child, son Joel Jasper Hembree, was riding upon the tongue of the wagon, and the motion threw him to the ground. "Joel fel off the waggeon tung & both wheels run over him," traveler William T. Newby wrote in his journal, according to a memorial by the Oregon-California Trails Association (via Find a Grave). The accident, in which two wheels drove quickly over the six-year-old's abdomen, occurred on July 18, 1843. The child died on July 19, and his family buried him just off the Oregon Trail on July 20.

Hembree's grave and gravestone — made by carving the child's last name and year of death into a literal stone — were not uncovered until 1961. Due to an encroaching reservoir, Hembree's body was exhumed. Initially buried in a dresser drawer, as that's what his family had at their disposal, the remains were reinterred on private land less than a mile away. In addition, Hembree's grave is the oldest ever found along the Oregon Trail.

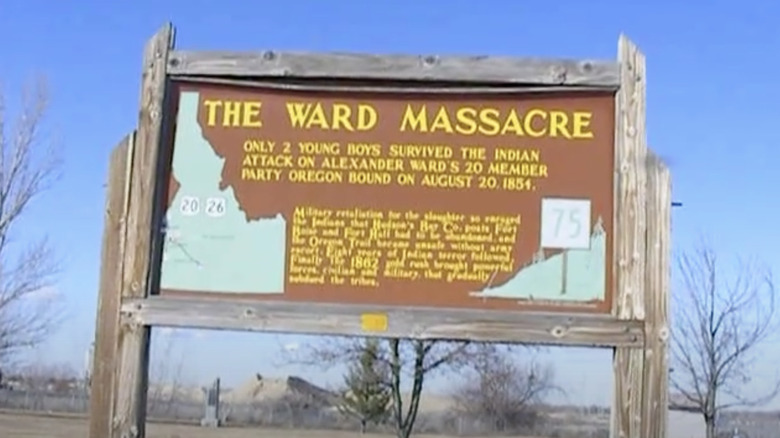

The Ward party was massacred

In the 1840s, the first decade in which the Oregon Trail began to be used in earnest, deadly altercations with Native American groups were a rare occurrence, with about 50 deaths attributed to such skirmishes. By 1860, that number reached around 400, with the Ward Massacre considered a turning point. Large numbers of emigrants were consistently making their way west to acquire land already occupied by Indigenous peoples, and those groups decided to fight back.

On August 20, 1854, Alexander Ward stopped his multi-wagon, 20-member caravan for a midday break along the river in the Boise Valley, in what's now Idaho. While the Ward party relaxed, a member of the Shoshone tribe approached the camp and stole a horse; one of the emigrants shot the thief dead. Not long after, more Shoshone, along with some members of the Snake group, retaliated, opening fire and attacking the Ward party. Many were fatally shot with arrows; some children were captured and burned to death over fires, while the women were sexually assaulted before they were killed. Of the 20 people in the group, 18 died that afternoon. The two survivors, Ward's teenage sons William and Newton, pretended to be dead from arrows shot into vital organs and then crawled 20 miles to safety at the nearest government outpost, Fort Boise.

Many of the Utter-Van Ornum party were killed in a violent raid

By the time the Oregon-Trail-following Van Ornum-Utter party reached Castle Creek — near what is now the Oregon-Idaho border — in September 1860, it included 44 people. On September 9, 1860, the wagon train was subject to an attack by a group of Shoshone, which attempted to upset and set loose the travelers' livestock. The party subdued the animals and gave the Shoshone a large stock of food to persuade them to leave, but were attacked again by about 100 Shoshone and Bannock about a mile further down the trail.

Three adults died in the fighting, which lasted into the next day's evening, at which point the emigrant party tried to escape. After abandoning four well-stocked wagons behind for the Shoshone and Bannock, they drove the train right through the amassed opposition; another group member died, and the fighting escalated. During this period, leader Elijah Utter was mortally wounded; a Shoshone delivered a fatal shot as he lay dying, and then Utter's wife and children were slaughtered, too.

The 27 remaining members of the group — not counting a few who got separated — managed to get a few miles down the road before the wagon-pulling oxen collapsed from exhaustion, forcing them to flee with almost no possessions or supplies. For a week they walked along the Snake River at night to avoid detection by Shoshone. On September 18, having traveled 75 miles, the party made a hidden camp at the Owyhee River to await a rescue group that Goodsel Munson and Christopher Trimble went to summon.

[Featured image by Ken Lund via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.0]

Overeating salmon killed one of the Utter-Van Ornum party, while others resorted to cannibalism

On September 22, 1860, Goodsel Munson and Christopher Trimble happened to run into some members of the Van Ornum-Utter party who had been separated from the main group: Charles Chaffee, and Joseph and Jacob Reith. Trimble returned to the survivor camp carrying some horsemeat, but shortly after he arrived, so did some Shoshone. The meeting was bittersweet, as while the Shoshone traded some salmon, they also confiscated their weapons and kidnapped Trimble. One traveler, starvation-weakened Daniel Chase, ate so much of the salmon that it killed him.

As for the scouts, Munson and Chaffee died of starvation before they could seek help; the Reiths successfully reached the Umatilla Agency on October 2 to request a rescue team. Unaware of that, another contingent departed the camp to seek assistance: the seven-member Van Ornum family, the two surviving Utter kids, and adult Samuel Gleason. Just miles in, they were attacked by Shoshone and four of the children were taken hostage, while the rest were quickly and brutally killed. Abigail Van Ornum had been whipped and scalped, Charles and Henry Utter shot with arrows, and Alexis Van Ornum, Marcus Van Ornum, and Samuel Gleason all died from having their throats slit.

Back at camp, four children died of starvation throughout October 1860. The surviving adults, desperate and at risk of starvation deaths themselves, ate the bodies. Finally, on October 24, an Army relief group found the survivors camp, but only 10 people remained. Of the Van Ornum children taken prisoner by Shoshone, only Reuben Van Ornum was recovered by the California Army in 1862; his three sisters died of starvation in captivity.