Things About World War II That Don't Make Sense

Though World War II is now the focus of many books, documentaries, and academic careers, there's a lot we still don't understand about it. This is reasonable in a broad sense, given the complicated nature of this war, which involved many different countries, each with its own unique background and place on the world stage. All told, from its beginnings with the 1939 invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany to the surrender of Japan on August 14, 1945, World War II involved about 70 nations, 70 million service members, and an estimated 17 million combatant deaths. On one side were the Allied powers, which came to include the Soviet Union, Great Britain, France, and the United States. On the opposing side were the Axis powers, namely Germany, Italy, and Japan. However, practically every nation was impacted by the war in some way.

All this complexity means that even small questions can spiral off into confusion. Why did some nations join one side and not another? Why did some attacks happen at a particular time and place? How did the U.S. nuclear weapons program prove itself to be capable of terrible power, while the Nazi-led version fizzled? Who really carried the blame for losing the war for Germany? And how did increasing tensions between the U.S. and Soviet Union play into the conflict even before the recognized start of the Cold War? These questions and more lead to some of the things about World War II that still don't make sense.

Why did Japan attack Pearl Harbor?

On the morning of December 7, 1941, almost 200 Japanese aircraft suddenly arrived in the airspace above the Pearl Harbor naval base in Honolulu, Hawaii. With a barrage of munitions, Japanese forces destroyed much of the U.S. fleet stationed there, including over 300 planes, eight battleships, and 2,335 U.S. service members and 68 civilians who died in the attack.

The attack sprang out of a tangled network of long-simmering rivalry and resentment between the U.S. and Japan. Many sources point to the beginnings of the tensions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when Japan began engaging in colonialist expansion and wars with China and Russia. But the U.S. was hardly a fan of Japan's attempts and put harsh economic sanctions on the island nation. By September 1940, Japan had entered into the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy and was barely budging in talks with the U.S.

By late 1941, Japan had effectively decided the U.S. was in its way. Yet the attack is still difficult to understand. U.S. forces were already considerable, thanks in part to a 1940 military draft that helped the armed services grow to almost 2.2 million members by December 1941. And though Japan felt an all-out attack was necessary to get the U.S. off its back, the nation didn't achieve near-total destruction of the fleet, leaving enough behind (including aircraft carriers and plenty of fuel and munitions) for America to enter the war with vigor.

Why didn't the U.S. better prepare for attack during World War II?

Conspiracy theorists occasionally claim U.S. officials knew of the Pearl Harbor attack well in advance, but deliberately failed to do anything to make the nation's entry into World War II an obvious necessity. This has been dismissed as an outright falsehood by legitimate historians, who make it clear that President Franklin D. Roosevelt was painfully surprised by the Japanese assault.

However, there is a grain of truth here: The U.S. had long managed tense relations with Japan and knew of the other nation's increasingly aggressive stance, and that was part of the motivation behind the Selective Training and Service Draft signed by FDR in September 1940. This was ostensibly the first U.S. peacetime draft but was clearly influenced by growing tensions with Japan and the fact that World War II had already begun in Europe.

What's more, Japanese officials warned U.S. military personnel on at least three occasions: October 16, November 24, and November 27, 1941. Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, co-commander of the base at Pearl Harbor, was directly cautioned by Japan to "execute an appropriate defensive deployment," though no other details were given (via Atomic Heritage Foundation). Kimmel and other commanders did prepare somewhat, but this included closely grouping craft on airfields — thus increasing their vulnerability to attack — and only partially increasing monitoring around the Hawaiian islands. It doesn't appear that FDR or any other officials in Washington, D.C., were aware of Japan's intentions until mere hours before the Pearl Harbor attack.

Why do people still think Erwin Rommel was a capable general?

Nazi general Erwin Rommel is sometimes depicted as a particularly canny military commander of the Axis powers, to the point where he was given the half-admiring moniker of the "Desert Fox" for his World War II campaigns in North Africa. Even Allied leaders admitted to some respect for Rommel, with no less a figure than U.K. Prime Minister Winston Churchill claiming that the German commander was a formidable adversary. Yet, this rise to prominence becomes quite a bit more confusing when you take a deeper look at Rommel's path to power and his decisions during the war.

Rob Citino, senior historian for the National World War II Museum, told Time that Rommel gained fame for his daring and decisive attacks on Allied forces, thanks in part because Hitler sponsored his early military career. Yet, those tactics came with a less admirable side. According to Citino's estimation, Rommel may have been more enamored of the glamor of war than the nitty-gritty details of supply chains and logistics.

Yet, attention to all those boring bits is often what makes for true success in war. If you're still not convinced, consider that Rommel never managed to seize control of the vital Suez Canal. Or, take a hard look at what may be his most significant failure: the inability to put a stop to the Allied invasion of Europe on D-Day. With such big fumbles on his resume, Rommel's enduring reputation makes little sense.

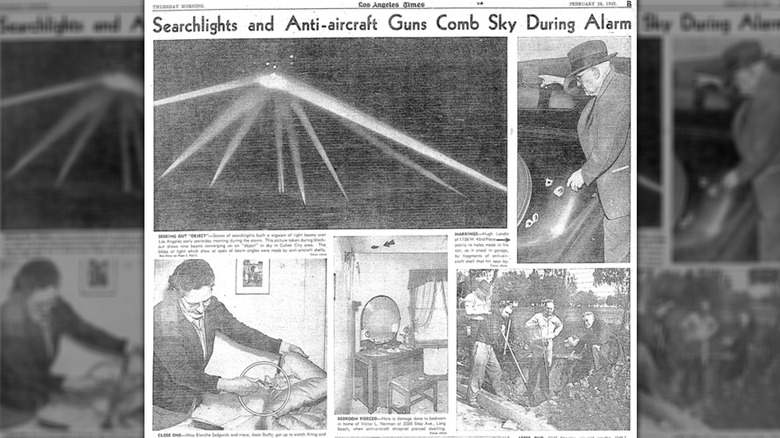

What the heck happened during the Battle of Los Angeles?

By early 1942, many Americans were understandably on edge. Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the U.S. officially entered the conflict just a day later by declaring war on Japan (Germany and Italy quickly followed suit by declaring war on the U.S.). For a while, at least, everyone seemed to spot invading craft approaching American shores or entering into American airspace. Sightings abounded along the West Coast, with many reports dismissed as mistaken identities. However, at least one confirmed attack on oil supplies by a Japanese submarine took place on February 23, 1942, though no one was hurt.

The next two days would ratchet up the tension even more for the people of Los Angeles and lead to one of World War II's most bizarre unsolved mysteries. On the night of February 24, military forces received instruction to prepare for an unconfirmed Japanese assault. In the first hours of February 25, radar supposedly picked up signs of an invading force. LA went into a blackout, searchlights pierced the skies, and troops began firing an estimated 1,400 anti-aircraft rounds at ... something.

Yet nothing came down. Some claimed to spot Japanese planes or a massive balloon, while others saw only clouds and smoke. No one was directly injured, though some reported deadly heart attacks and car accidents, while shrapnel damaged homes. The most likely explanation is a false alarm, though the scope of the panic remains confusing.

How advanced were WWII Nazi rockets, really?

For at least some Allied strategists and scientists, the specter of a Nazi weapons program was haunting. After all, a German bombing campaign — the Blitz — had torn apart London and other British cities from September 1940 to May 1941 (and bombed Buckingham Palace multiple times). Soon reports came in regarding the V-2 missile, the product of a seemingly superpowered ballistics program that, if it had only gotten started earlier, could have perhaps turned the tide of war in Germany's favor.

Well, maybe. By the 1940s, many were anxious about what seemed to be a growing Nazi war machine. During the war itself, Allied bombing raids routinely hit weapons depots and production sites where new jet propulsion technology was used to power missiles. The appearance of the long-range V-1 rocket in June 1944 and the V-2 in September of that year made things seem all the more dire.

But were Nazi rocket scientists and pilots really that successful? Despite the fearsome reputation, missiles often missed the mark and simply tumbled from the sky. Others misfired over unpopulated areas, which surely stung even more when Nazi officials looked at the hefty expense reports for the V-2 program. Meanwhile, Allied forces routinely exploited weaknesses in flight patterns to shoot down rockets. All told, the jet engine technology was apparently too experimental for the rush of war, making the half-awed postwar impression of the program (not to mention the effort put into it by Germany) seriously odd.

Why did the Nazi nuclear program fail?

For a while at least, it must have seemed as if Germany had a nuclear weapons program on lock. Sure, information about what exactly was going on inside the increasingly fascistic regime was hard to come by. Who would want to share their nuclear secrets, anyway? But by the late 1930s, German scientists had already conducted and publicized their experiments on nuclear fission, in which splitting atoms produced potentially immense (and destructive) power. As Nazi Germany formally entered into war and began taking territory across Europe, its scientists worked to refine their materials and more reliably produce enriched uranium for use in weapons.

With the hindsight of history and the devastation first wrought on Hiroshima and Nagasaki by American nuclear bombs, it's clear that the Nazi nuclear program failed. But why? Germany once had seriously advanced science at its fingertips, as evidenced by the U.S. push to incorporate Nazi scientists and engineers into its own postwar programs via Operation Paperclip.

Part of the explanation centers on the fact that refining uranium and developing weapons was massively complicated and time-consuming. The Nazi government, lulled by the successes of conventional weapons, may have neglected to fund the nuclear program until it was too late (or may have been scared off by the expensive but only semi-successful V-2 rocket program). It didn't help that key German intellectuals like Albert Einstein fled Europe to avoid antisemitic persecution ... and subsequently lent their help to the American Manhattan Project.

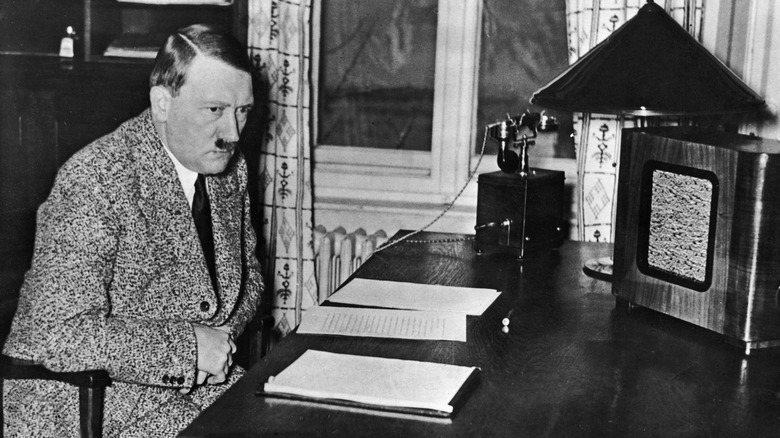

Why do people still think Germany's failure was all Hitler's fault?

Much of the blame for Germany's loss is assigned to Adolf Hitler. Even previously loyal Nazi generals later said their country's weapons program was gummed up by Hitler's reluctance and cost Germany the war. Yet, while there's hardly any need to defend someone who is remembered as one of the worst monsters in human history, it's not totally accurate to say Hitler lost the war all by himself. In fact, just a slightly close look at the state of affairs by the end of World War II makes this assumption all the more nonsensical.

Take the vital detail that many of the reports solely blaming Hitler came from Nazi generals and other officers, all of whom could have used a convenient scapegoat in the aftermath of the war. And though Hitler was making high-level decisions during the war, he wasn't necessarily getting into the nitty-gritty of logistics or troop supplies, much less things Germany itself was short on, like food, oil, and steel. This resulted in a growing anxiety over resources that may have even pushed Nazi forces to attempt a takeover of Soviet territory, which proved to be a resource-consuming disaster.

That attempt, known as Operation Barbarossa, along with Germany's broader failures, simply can't all be the fault of a single man who (though obviously powerful and awful) was working within a system of many other powerful players.

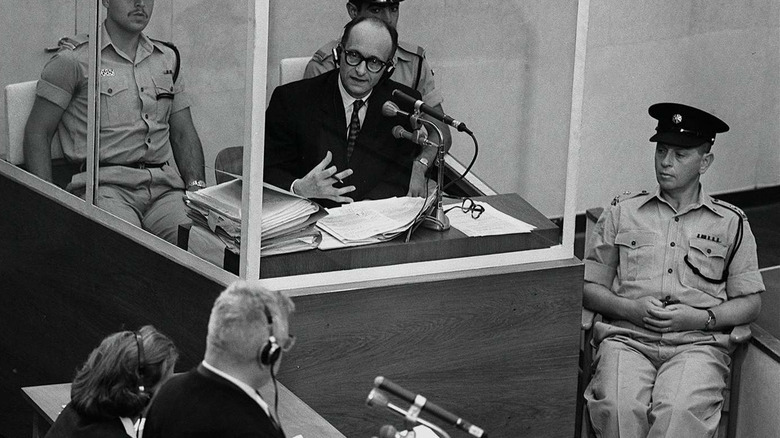

How did WWII ratlines manage to work as well as they did?

Emerging evidence of the Holocaust motivated the hunt for missing war criminals. Though some of the most notorious Nazis were captured or met a poor end in the final days of the war, some fled Europe along secret routes that came to be known as ratlines. Like many fleeing war criminals who found sympathetic governments in South America, the SS officer who organized much of the Holocaust, Adolf Eichmann, fled to Argentina and was captured there in 1960 after an intense manhunt. Argentine president Juan Perón was a bit of a fan of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini's work and was reportedly interested in recruiting valuable scientists and other skilled Germans. Some received Argentine visas, while others received help from Vatican officials and the mysterious Odessa organization.

Some of those who escaped were fairly high-level or notorious Nazis, like Josef Mengele, the ghoulish doctor who forced Auschwitz inmates to undergo medical experiments. Mengele was never apprehended and died in Brazil in 1979.

So, how did the rats stay hidden for so long? For one, there were the aforementioned sympathetic governments, which includes not just Peronist Argentina but Chile under dictator Augusto Pinochet. Chile stalled when West Germany called for the extradition of SS Colonel Walter Rauff, who coordinated the construction of mobile gassing units. Rauff died in 1984, having only been briefly imprisoned. Catholic clergy also sometimes helped ferry Nazis through ratlines, though it's still not clear how much Pope Pius XII knew about this. Ultimately, though there wasn't a shadowy group coordinating it all, the combined effort of post-war Nazi supporters — some loud, some quiet, many dubiously-funded and well-connected — that made it happen.

Why were German prisoners of war treated better than some Americans?

From 1943 to 1945, an estimated 425,000 German prisoners of war (POW) were sent to detention centers across the U.S. Many arrived in rural Texas, where extra land made it easier to establish camps. Texas was also selected because the 1929 Geneva Convention maintained that POWs should be sent somewhere with a climate similar to where they were captured. For a German soldier apprehended in North Africa, Texas was deemed a close-enough climatological match.

The Geneva Convention also required that POWs and their guards live in similar quarters, meaning that conditions were decent for German prisoners — to the point where locals derisively called a few Texas camps the "Fritz Ritz." Captured soldiers likewise weren't required to work, though some did so anyway to alleviate the boredom and earn a bit of money. Conditions were so good that very few tried to escape, and those who did hardly appeared to fear much retaliation. After the war, some attempted to stay in the U.S. and even occasionally succeeded in becoming American citizens.

The most nonsensical part of this situation is its contrast with the treatment of Japanese Americans during the war. On February 19, 1942, FDR signed Executive Order 9066, ostensibly to keep American military zones safe from foreign infiltrators. What it really meant was that some 120,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast (many of whom were citizens) were forcibly relocated to internment camps with little regard for their livelihoods, property, or civil rights.

The real justifications for bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki are tangled

For quite a few people on the Allied side, the nuclear bombings of Japanese cities Hiroshima and Nagasaki were a necessary evil. The bombings, which took place on August 6 and August 9, 1945, respectively, killed tens of thousands of people immediately and left many more to painful deaths from radiation exposure. Yet, it also seemingly ended the war, with the Japanese surrender coming just one day after the destruction in Nagasaki. Internally, military officials also claimed that a land invasion would kill up to one million U.S. service members and would claim even more Japanese lives.

But that official explanation alone doesn't quite make sense. If Japan continued to resist and U.S. plans for a land invasion went ahead in what the Allied forces called Operation Downfall, it's possible that an already resource-stressed Japan would have capitulated. Or, it could have been that fierce Japanese resistance, like that seen from both combatants and civilians at Okinawa and Iwo Jima, would have spiraled into a bloody guerrilla war.

Even if the nuclear strikes in Japan avoided all that at a terrible price, they served additional purposes. The Soviet Union, which was quickly emerging as a major rival to the U.S., now saw what America was capable of doing ... as did any leaders sympathetic to Soviet communism. Still, as survivors of the bombings, activists, and many historians may argue, the means to the end may still not make much sense.

Why did Winston Churchill put Britain in such a vulnerable spot leading up to WWII?

Today, Winston Churchill may often be depicted as a heroic Allied leader during WWII, having been appointed Prime Minister by George VI in 1940. He certainly deserves great credit for leading Britain through the dark days of WWII, but the more complex reality is that Churchill wasn't always rallying a nation against the Axis powers. In fact, in his pre-war days as a politician, he advocated for a policy that arguably put Britain in great danger.

Now known as the "10-year rule", this actually took root in 1919. It directed military officials to plan the next decade with the assumption that Britain wouldn't enter into any major war. In effect, it meant the nation's treasury had some control over the defense budget, though historians have argued that the effect of the rule has been exaggerated. But there's still a case to be made that this policy hampered defense, and Churchill certainly had a role to play here, as he was Chancellor of the Exchequer from late 1924 until 1929.

However, Churchill had few easy answers. When he told the House of Commons in June 1930 "I believe that wars are over for our day" (via U.K. Parliament), could he have really predicted another bloody global conflict? Just a few years later, Churchill recognized the changing tide and loudly argued for British armament.

Neville Chamberlain's WWII legacy is out of step with his political reality

Neville Chamberlain, who preceded Winston Churchill as Prime Minister from 1937 to 1940, has a notorious reputation nowadays for pre-war attempts to appease Adolf Hitler. In September 1938, political tensions along the Czech border were growing dire. Germans living in a region there known as the Sudetenland were claiming political violence; Hitler found that easy justification for placing German troops there. Chamberlain flew to meet with Hitler, attempting to broker an agreement that would avoid war. Working in concert with other European leaders, Chamberlain offered up the Sudetenland to Germany if Hitler would promise to stop the land-grabbing. Hitler agreed ... presumably with his fingers crossed behind his back, as Germany fully invaded Czechoslovakia and then Poland in 1939.

But does Chamberlain's lingering dishonor fully make sense? Yes, in hindsight, working so closely with Hitler is a very, very bad look. But, during the 1930s, the public wasn't quite so put off by appeasement. Many still vividly remembered the horrors of WWI and supported policies that would stave off another major global conflict. The majority of politicians more or less agreed, while a protesting Churchill was one of the odd ones out and hadn't exactly made himself popular when loudly protesting Hitler. While he wasn't perfect, Chamberlain also had to balance the demands of the British people, the urging of other world leaders, and the shadow of war to keep carnage from happening.

Why did Britain give the Soviet Union a break for invading Poland?

As far as Britain and much of the rest of the world was concerned, Germany's September 1939 invasion of Poland was the last straw. At the same time, Germany had entered into a nonaggression agreement with the Soviet Union, known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact or German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact. The Soviet motivation: stave off war with Germany, allowing it to build up its own defenses. It likely didn't hurt that the Soviet Union would get some of its own territory in eastern Europe. Adolf Hitler, meanwhile, signed the agreement to get a possible enemy off Germany's back while it consumed most of Europe.

This meant the Soviets also invaded of Poland in September 1939. But, while Britain took this as a sign that Nazi Germany was definitely its enemy now, the Soviet Union would become one of the "Big Three" of the Allied powers. So, why did Joseph Stalin get a pass for his invasion while Hitler became enemy No. 1? From a pragmatic perspective, the U.S.S.R. was simply too powerful an ally to ignore. It's not as if the Soviets were especially fond of Germany, especially after Hitler went ahead and snatched back eastern Poland in June 1941. As much as Britain and the other Allies had to engage in realpolitik, however, this alliance would remain tenuous until it broke down in the complicated aftermath of the Cold War.

What was going on with Germany's drug use during the Second World War?

You may come across the notion that, in Nazi Germany, drug use was criminalized and anyone dealing with substance use issues were "othered" and treated as "anti-socials." This isn't really true, but the Nazi regime did have a confusingly complicated take on substances. Part of the issue was rooted in the distinctions made between people who used different substances in German society at the time. Those struggling with alcoholism could find themselves up for all manners of ostracization and punishment, which grew to include forced sterilization (though not en masse). While impairment via other drug usage wasn't exactly smiled upon, officials were more likely to recognize it as a societal problem requiring treatment, not punishment.

A 2016 paper published in Holocaust and Genocide Studies found that Germans who committed wartime atrocities were more likely to engage in alcohol usage. German soldiers were often encouraged to use amphetamines, skipping past concerns of health issues to do away with pesky necessities like sleeping. The most notorious may be Pervitin, of which over 35 million tablets were issued to frontline soldiers in 1940. Meanwhile, Nazi leaders didn't seem terribly worried about Germany's health when it came to their own personal usage. Adolf Hitler himself was reportedly swimming in medications issued by Dr. Theodor Morell. The rather unscrupulous Morell regularly issued stimulants, depressants, and opiates to the Führer, including a German version of oxycodone.

How did the Hugo Boss uniform myth during WWII get so much traction?

The Hugo Boss myth goes something like this: German clothing brand Hugo Boss designed SS uniforms, managed to survive the war, and moved into the world of high fashion seemingly without incident. There's a germ of truth at the center of the tale. Hugo Boss was a man who started out as a tailor and eventually began a small-scale clothing business in Germany after World War I. In 1931, he really did sign off on a contract to make uniforms for the SS while also churning out everyday clothes. Eventually, his company switched to making solely Nazi uniforms, though Boss never actually designed SS uniforms.

The true confusion was maybe at the modern Hugo Boss company itself. Boss died in 1948, leaving his family to take over his business and turn to suit-making in the 1960s. Somewhere along the line, Boss' Nazi links were nearly forgotten, leaving some company members surprised when they learned about the connection in 1997. At that point, the Boss family — which knew quite well that the founder was a member of the Nazi's National Socialist party and who cherished a photo of him with Adolf Hitler — was not involved with the company bearing the same name. In 1999, Hugo Boss, the company, was faced with legal proceedings concerning its use of forced labor during WWII, and officially apologized for its Nazi past in 2011.

Why do so many think winter alone saved the USSR from Germany in 1941?

One take on the failed German invasion of Russia maintains that Nazi forces were somehow unaware that Russia gets really, really cold in the winter. Named after a medieval Holy Roman emperor, Adolf Hitler's Operation Barbarossa was officially ordered in December 1940 and launched the following summer. It sent more than 3.5 million troops to a front that sprawled some 1,800 miles long. At first, the force (consisting of Army Groups North, Centre, and South) seemed to make quite a lot of progress. Only, Army Group Centre, bound for Moscow, started to see major supply issues, and was redirected elsewhere when it was just 220 miles from Moscow. Hitler had decided that resource-rich Ukraine would be a better target. In fact, they did take Kyiv and deliver further blows against the U.S.S.R. (including the important WWII battle of the Siege of Leningrad) before returning to strike Moscow in October 1941.

At this point, things were getting chilly. But, while researchers agree that frigid conditions were hardly useful to the Germans, a case study of winter warfare in Russia published by the Combat Studies Institute found that frosty weather hasn't historically been a decisive factor. Hitler failed in Russia for a complex variety of reasons, including the notorious rasputitsa season, in which pre-winter rains turn dirt roads into nigh-impassable expanses of mud. This slowed Germans down considerably, exhausting troops (who often lacked cold weather gear), limiting supplies, and giving the Soviets valuable time to regroup. The sheer size of the territory, along with fierce Soviet resistance, further compounded the failure.

Why did some Americans support Germany during WWII?

Today, you are ideally in the sort of environment where the notion of lending support to Nazi Germany sounds confusing, if not downright horrifying. But what made some Americans in the 1930s and '40s rather more friendly to Adolf Hitler and his ideas? The uncomfortable truth is that more than a few Americans were sympathetic to the Nazi cause. Take the example of the 1939 Nazi rally held in New York City's Madison Square Garden, which brought in crowds of more than 20,000. It was sponsored by the German American Bund, an organization that didn't just hold rallies, but also sold literature, organized youth camps, and did more to promote its now (hopefully) odd mélange of U.S. patriotism and Nazi ideology.

What was going on? Part of the interest is connected to the rise of white supremacist hate groups in the U.S., which were often interested in notions of racial and social "purity" echoed in German thought. There were also Americans of German descent who, though they might be a generation or more removed from living in Europe, were reluctant to levy criticism (especially considering discrimination against German immigrants after WWI).

Lest you think part of the problem was that people were simply unaware of the atrocities being committed in Europe, don't be so sure. A 2023 paper in The British Journal of Sociology found plenty of newspapers and other publications from the time that reported on the escalating horrors under the Nazi regime.

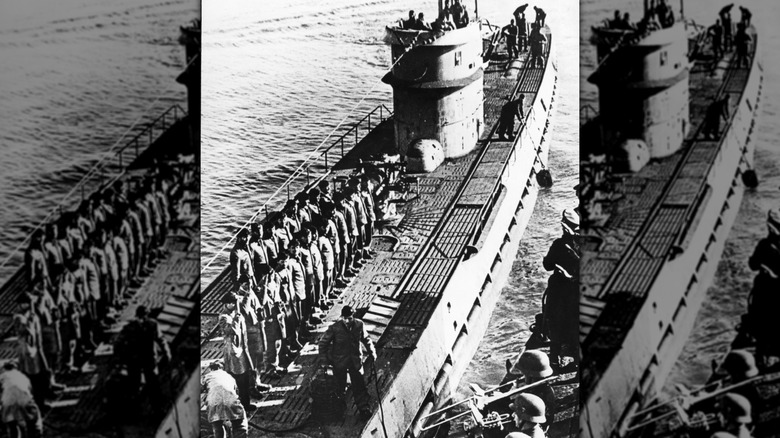

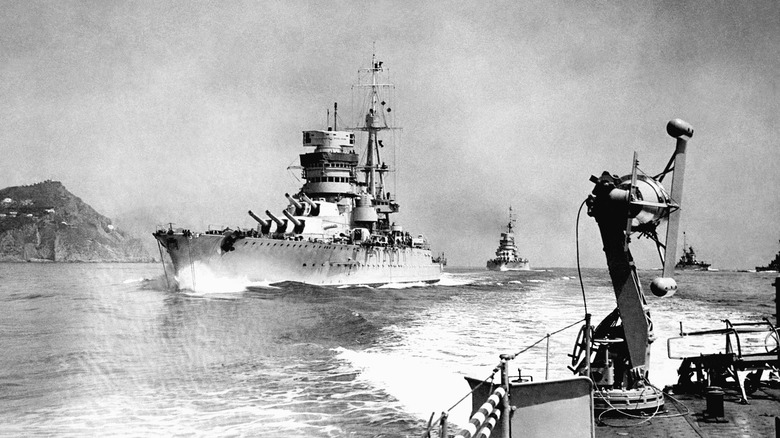

Why didn't Germany invest more in its navy during the Second World War?

Though German Admiral Karl Dönitz built up a submarine force that was once a major threat to the Allies, the specter of U-boats became less dire as the war continued. But why did this torpedo-firing, blockade-building force wither away? A lack of funds and attention, made all the more confusing given how naval power allowed Allied nations to dominate a key sphere of war. If Adolf Hitler ever admitted that inattention to naval strategy was biting Germany back, and hard, it came far too late to do much about the well-armed fleet of over 7,000 Allied ships.

As Hitler biographer Professor Frank McDonough told The Society for Nautical Research, "Hitler wasn't a sailor, for sure." McDonough argued that Hitler was so focused on making gains in Europe that he greatly neglected the navy, while the plans that were in place were often impractical. "They had a plan, it was called the Z plan, to build the eight battleships by 1942 or whatever, but it was impossible," McDonough said. "That's why they lost the Battle of Britain." Meanwhile, though Dönitz advocated for building more submarines and attacking merchant ships, those pricey vessels likewise never appeared en masse. In the meantime, Allied militaries were able to come up with ways to strike back against German vessels, to the point where McDonough quoted a late-war 75% mortality rate for German submariners.

Why did the Axis powers think they might win the war?

While it's hardly useful to pull a Monday morning quarterback move on the Second World War, some things do seem pretty obvious in retrospect. One of the most major: how did the Axis powers ever hope to win the war? Sure, if all you go on is the self-mythologizing and grandiose speeches, it may seem like they stood a good chance. But a clearer-eyed look at the practicalities dulls that shine considerably.

It wasn't all bad news, at least not at first. As war dawned, Axis powers like Germany and Japan had built a fearsome reputation as canny warmongers hungry for territory. Germany was also busy militarizing in defiance of the weakly-enforced, post-WWI Treaty of Versailles. Moreover, many in Europe were wary of engaging in another world war so soon on the heels of a first one (or simply didn't want to talk about the destruction and pain of WWI).

However, when the Soviets and Americans joined the Allies, they brought together more robust economies, healthier supply chains, and higher populations. A booming war effort meant that even relatively small nations like Britain built mighty fighting forces and far-ranging transportation networks. Germany, Japan, and Italy simply never had the same sort of infrastructure that the combined Allied countries built — for example, there were never any active German aircraft carriers despite attempts to build one. Meanwhile, the Allies already had a robust naval force that they only increased during the war.

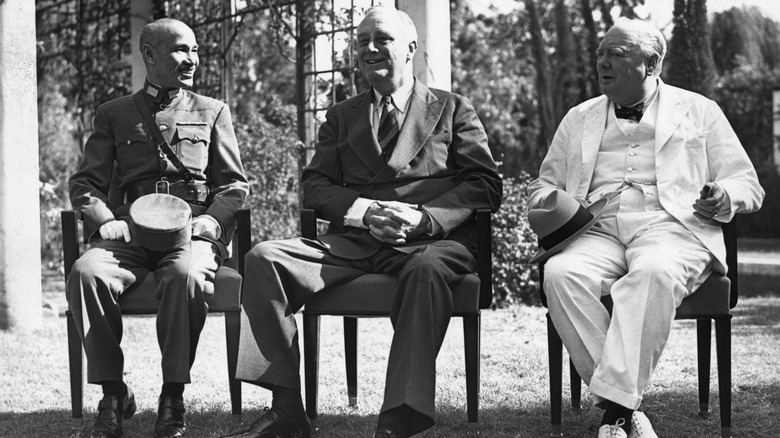

Why do Americans so often forget China's part in WWII?

At the outbreak of WWII, China had already been embroiled in the nasty Second Sino-Japanese War (which, yes, followed an also-awful First Sino-Japanese War and plenty of conflict in between). By late 1937, Japanese forces had taken both Beijing and Shanghai and were in the process of taking Nanjing (also known at the time as Nanking) to the tune of hundreds of thousands of civilian deaths. A tenuous truce was made with the Nationalists led by Chiang Kai-Shek, while Communists mounted guerilla resistance. As 1938 dawned and WWII was on the horizon, Japan's advance into China faltered and other countries got more involved. From the Soviet perspective, a territory-hungry Japan parked on its eastern border was hardly welcome, so Joseph Stalin sent weapons to Nationalist forces while the U.S. sent supplies and embargoed trade with Japan. During the war, Chinese troops continued fighting the Japanese while also allowing other Allies to use air bases for key attacks in the Pacific Theatre.

As with so many wartime statistics, getting an exact figure is difficult, but many estimate Chinese deaths during the war totaled 12 to 14 million or perhaps even higher. The causes include not just war, but disease, food insecurity, and drowning (in 1938, Nationalists broke open dikes along the Yellow River to defeat Japanese forces). After the war, Chiang's Nationalist government quickly fell to pieces and Communists led by Mao Zedong took over in 1949 — the Chinese people soon faced the terrible consequences of the Great Leap Forward.

Why do people buy into the clean Wehrmacht myth?

For many, one of the most chilling conundrums of the Second World War is how so many Germans and other Europeans managed to turn a blind eye to the Holocaust. With six million Jewish people victims of the genocide (along with millions more non-Jewish people also murdered), and the construction of concentration camps and obvious transport of victims, how could anyone fool themselves? Yet some still wish to indulge in the myth of the "clean" Wehrmacht," in which the non-Nazi German military somehow didn't know about or participate in the Holocaust or other war crimes.

However, there's demonstrable evidence that Wehrmacht personnel knew plenty about it all. When it comes to the Holocaust, the complicated picture that emerges shows that at least some soldiers expressed discontent with the genocide — but they had to have known about it to dissent in the first place. For instance, Wehrmacht commander Johannes Blaskowitz is recorded complaining about the SS-led murder of 10,000 Jewish and Polish people in early 1940 (via Holocaust Encyclopedia). Certainly, by the mid-1930s, German military members were obliged to swear "unconditional obedience" to Adolf Hitler. As for other war crimes, Wehrmacht soldiers openly admitted to the widespread killing of combatants and civilians, both closer to home and in Soviet territory. It was especially brutal in the mistreatment of Soviet prisoners of war, with conditions so awful that an estimated 2 million POWs died in German custody over just eight months.