What Happened To The Bodies Of Hitler's Closest Allies?

Throughout his life, Adolf Hitler threatened suicide. After the failure of the Beer Hall Putsch, with the Nazis' grab for power and Hitler himself injured and in hiding, he had to be physically restrained from putting a pistol to his head. Vowing to kill himself was a frequent response by Hitler whenever things didn't go his way, according to Psychiatric Times.

By 1945, all of Hitler's plans had collapsed around him. The Allies were breaking through Nazi Germany's armies and the Soviets were upon Berlin; the Third Reich's days were plainly numbered. The full extent of Nazi atrocities against the Jewish people was coming to light. And Hitler himself had been pinned down to his bunker for months, where he learned of the grisly fate of his fellow fascist leader Benito Mussolini. Unwilling to face a comparable scene in the event of his capture, or the prospect of a trial and execution, Hitler finally went through with his long-threatened plans. He tested cyanide on his dog, and his lover Eva Braun died from cyanide poisoning before Hitler shot himself. By his will, the bodies were burned, though his remains would be dug up and shifted around several times before finally being cremated and scattered in the 1970s.

Hitler's death came ahead of mass suicides throughout Germany, though the Nazi propaganda machine obscured the cause of his death. Some in the Nazi leadership who did know emulated the Führer, or died by suicide under other circumstances. Other close allies to Hitler were executed after trial or lived to see natural ends. And their bodies were variously burned, buried, or the subject of political fears and campaigns.

Goebbels followed Hitler in death

Adolf Hitler owed a good measure of his and the Nazi party's success to the party's propaganda mastermind, Joseph Goebbels. Educated in German philology with talents in literature and theater, Goebbels was not a frothing antisemite in his youth. He might have gone another way after World War I. But he fell into the Nazi orbit in the 1920s and quickly attached himself to Hitler, becoming one of the inner circle. He eventually bought into his own oratory, which rivaled Hitler's own at Nazi rallies. Goebbels' propaganda tactics shaped Hitler's image in the eyes of the German people — and stoked the fires of antisemitism.

Hitler publicly praised Goebbels' efforts and gave him a series of promotions. In turn, Goebbels was utterly devoted to Hitler. As World War II turned against Germany, Goebbels followed his Führer into the bunker under Berlin. He was the last of the Nazi leadership that had brought Hitler to power to remain at his side. When Hitler died, Goebbels was made chancellor. But rather than preside over the final collapse of Nazi Germany, Goebbels chose to follow his leader. He and his wife poisoned their six children then died by suicide.

The Soviets found Goebbels' body in the garden of the Reich Chancellery buried by order of the KGB in February 1946 at a military base. But when that base was turned over to East Germany in the 1970s, Goebbels was exhumed and his remains burned. The ashes were later scattered over a tributary of the Elbe River, according to the book "Hitler's death : Russia's Last Great Secret from the Files of the KGB."

Himmler's grave is unknown

In his private life, Adolf Hitler wasn't close to Heinrich Himmler. They rarely socialized, and Hitler was contemptuous of Himmler's fascination with mysticism. But he also referred to Himmler as "the faithful Heinrich" per Aish, for his utter devotion. Himmler wasn't just one of Hitler's strongest supporters; as head of the SS, he was responsible for planning and coordinating the murder of millions. It is Himmler who is often described as the chief architect of the Holocaust.

But the faithful Heinrich's loyalty gave way in the end. In 1945, he tried negotiating for Germany's surrender to the West and a new alliance against Russia, with Himmler taking over as leader of Germany. For this betrayal, Hitler stripped Himmler of rank and ordered his arrest. An attempt to flee ended in Himmler's capture by the Russians. They delivered him to the British, who knew him; his hastily prepared credentials gave him away. Hitler was dead by then, and Himmler's captors were determined not to allow him to follow suit. They thoroughly inspected him for concealed poison. When they inspected his mouth, Himmler jerked away from the doctor and bit down on a cyanide capsule, according to "Heinrich Himmler : the Sinister Life of the Head of the SS and Gestapo." Himmler died by suicide on May 23, 1945.

Himmler's body was covered in army blankets and tied up in mesh and wire. The British buried him in the Lüneburger Heath, the site of the German surrender. While the region of his burial has been publicized, its location hasn't. To this day, Himmler rests in an anonymous and unknown grave.

Bormann's body was found in a construction site

The myth that Adolf Hitler escaped the Allies and fled to Argentina is a stubborn one. He wasn't the only member of the Nazi high command who was thought to have slipped away either. It was more credibly reported that Martin Bormann, private secretary to Hitler, escaped at the end of WWII. For almost 30 years, he was suspected to be at large and remained one of Europe's most wanted war criminals. Bormann was accused of political violence as early as 1924 and wormed his way into Hitler's confidence through his service to Rudolf Hess, and once he was installed at Hitler's side, he carefully manipulated both access to the Führer and Hitler's own idiosyncrasies.

Unable to find Bormann after the fall of Berlin, the Allies tried him in absentia at Nuremberg. He was the only major figure the Allies sought to try who couldn't be found. The sentence of death was passed down, and as the years passed, Nazi hunters still looked for him. A 1973 New York Times article said that former Nazis branded him a Russian spy who had squirreled himself away behind the Iron Curtain; investigative writers thought they traced him to South America, with Argentina, Chile, and Paraguay all mentioned as potential hiding places.

Finally, in 1972, two skeletons were unearthed during a construction project in West Berlin. Forensic analysis soon pegged one of them as Bormann's, which was enough for the authorities to move his classification from "missing" to "dead." DNA confirmed the identification in 1998. It's assumed that Bormann died while trying to escape at the end of the war.

Goring was cremated after suicide

"[I ask] to be spared the ignominy of a hanging and be allowed to die as a soldier before a firing squad." That was the last request of Hermann Göring (per Roger Manvell's "Goering: The Rise and Fall of the Notorious Nazi Leader"). Soldiery was Göring's great aspiration, one he'd pursued all his life. Raised in a castle as a child, he trained for an army career and served in the Air Force during World War I. He assumed command of the SA in the early days of the Nazi party. Political victories by the Nazis led to ministerial work for Göring, and to popular appeal among the masses. But Göring was also the man behind the Luftwaffe, launched to devastating effect in the early days of World War II.

As the war soured though, Göring proved unwilling to confront Adolf Hitler's blind spots on military policy and incapable of the rigor and stamina needed for the war. Brittanica says he suffered from drug addiction. He was resented by other members of Hitler's inner circle. At war's end, he tried to usurp Hitler's powers; once captured and brought to Nuremberg, he conducted himself as the star defendant. His defense didn't save him from conviction, and his emotional appeal for a firing squad was rejected.

Göring, among the most prominent criminals tried at Nuremberg, was to be the first executed. But denied a soldier's death, Göring died by poison hidden away in his pomade on October 15, 1946. His body was burned along with those executed that day, and all their ashes were scattered.

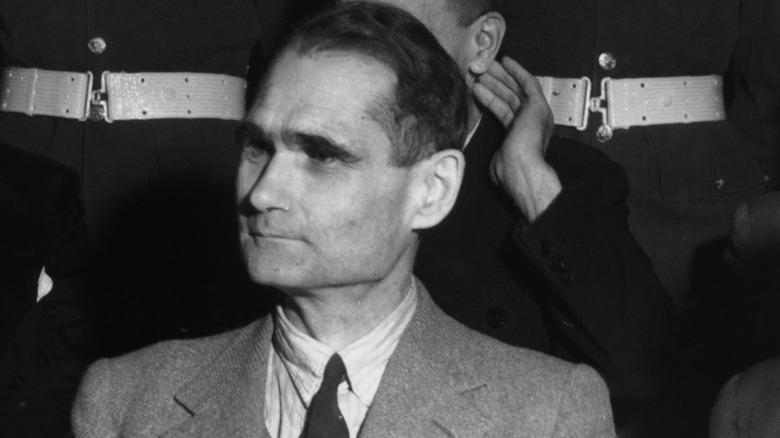

Hess was buried twice before being cremated

More than 80 years on, it's still unclear why Rudolf Hess, deputy Führer of Nazi Germany, flew off to Scotland in the middle of World War II. Hess's given reason — that he wanted to broker peace between Germany and Britain — was supposedly done on his own initiative. Adolf Hitler scorned his deputy's actions; the episode was reportedly just the last straw in the gradual deterioration of their relationship. But a persistent, tenuous theory holds that Hitler himself sent Hess on the mission as part of complicated negotiations that might have put Britain and Germany against Russia, per Smithsonian. Others suggest that Britain lured Hess into a trap.

Whatever motivated the flight, it achieved nothing except Hess's capture as a prisoner of war. Examinations while in custody suggested his deteriorating mental health, not helped by his later claims that a supernatural presence moved him to make his flight. Though he was tried at Nuremberg with other high-ranking Nazi officials, Hess escaped the death sentence. Instead, he was incarcerated at Spandau prison. His sentence was for life, and for the last 20 years of his life, he was the only prisoner at Spandau. Hess died by suicide in 1987 at 93.

According to Spiegel, in his will, Hess asked to be buried in Wunsiedel in the same cemetery as his parents, but the responsible parish initially refused; they wanted no gathering place for neo-Nazis. A burial was eventually allowed, but as the parish feared, Nazi sympathizers began making pilgrimages to Hess's grave. In 2011, with the reluctant consent of his family, Hess was exhumed, cremated, and scattered at sea.

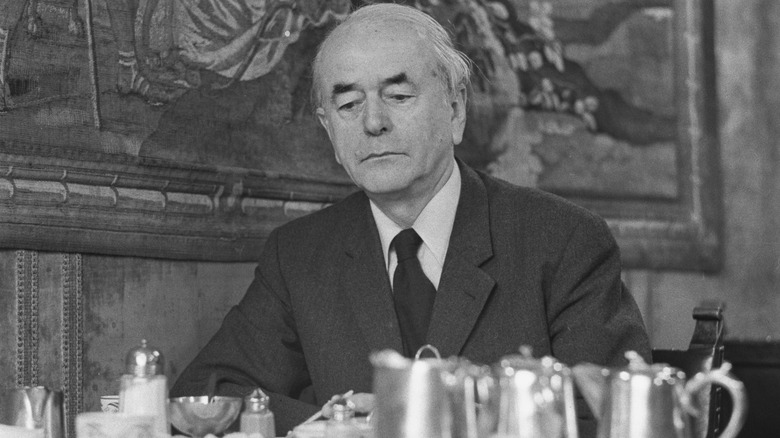

Speer was cremated

If there can be such a thing as a "good Nazi," Albert Speer tried to play the part. He was pleasant, cooperative, and frank with his American interrogators when he was captured at Glucksburg Castle in 1945. As Adolf Hitler's chief architect and, later, minister of armaments and war production, he was seen as a valuable asset in concluding the war. In the Americans' hands, at Nuremberg, and throughout his postwar life, Speer presented himself as a penitent man who could offer an insider's guide to Nazi Germany — all while noting the part he played in reducing the power of the military and refusing the maddest of Hitler's decrees.

For his cooperation and claims of remorse, Speer escaped the death penalty and life imprisonment. He emerged from his 20-year sentence rich and, to a degree, respected. But Smithsonian reports that shows of contrition papered over the extent to which he benefited from slave labor and his knowledge and complicity in the Holocaust. Various writers challenged Speer's self-image, but it remained intact when he died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1981.

At 76, Speer had made it to old age and remade himself in the eyes of the world when so many of his wartime peers died ignominiously, exposed as monsters. His remains also saw a more dignified treatment; after a private ceremony, they were cremated and interred. His family gravestone can be found in Heidelberg. But the years since Speer's death have seen his carefully cultivated image as the "good Nazi" slowly but emphatically shredded; his name is now as blood-soaked as any of the Nazi high command.

Ribbentrop was burned after hanging

As a diplomat and, later, foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop's most notable international agreements helped enable Nazi Germany's aggressions. His Anglo-German Naval Agreement let the German navy rearm, he negotiated the alliances with Japan and Italy, and the Non-Aggression Pact he arranged with the Soviet Union opened the door to the Nazi invasion of Poland. But the wars Ribbentrop helped to bring about undermined his own position within the Third Reich. With the world at war and Germany determined to fight, there was less and less need for him, and his reputation was clouded within Nazism by the participation of some of his staff in the July 20 plot. He did maintain a role in arranging for other Axis powers to send their Jewish populations to Germany for extermination.

Ribbentrop was taken captive in June 1945. Rather audaciously for a diplomat, the Anglophobic Ribbentrop was found to have prepared a letter castigating Britain and Winston Churchill for not cooperating with Germany against Russia. Disdained by the Allies and his fellow Nazis, he appeared before the tribunal at Nuremberg and sentenced to death by hanging.

It was the same fate handed down to many Nazis tried at Nuremberg, including Hermann Göring — the first Nazi to face the noose. But after his death by suicide, Ribbentrop was moved to the front of the line. His neck didn't break when he dropped; It took him 14 minutes to die by strangulation, per the University of Georgia School of Law. Once he was finally dead, Ribbentrop was cremated along with the rest of the executed Nazis. Their ashes were scattered over the Iser River.

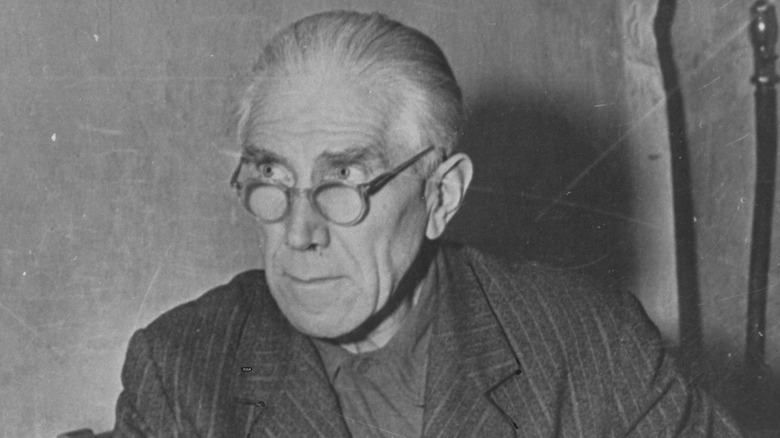

Papen was buried in his birthplace

Franz von Papen was not a member of the Nazi high command. He wasn't a close personal associate of Adolf Hitler's. After 1934, he lost whatever power he once held in the German government and was shifted into diplomatic affairs. But Papen has long been branded as the man most responsible for bringing Hitler and the Nazis to power. He was chancellor in 1932, when the Nazis held the largest bloc of seats in the Reichstag, and he started Germany down the road to authoritarian government. In this, he was opposed by General Kurt von Schleicher, aide to President Paul von Hindenburg, and by a sufficient mass of legislatures and citizens to force him from the chancellorship. Partially out of revenge, and partially in line with a conservative view that the Nazis could be a controllable junior partner, Papen convinced Hindenburg to appoint Hitler chancellor.

After the war, and for the rest of his life, Papen tried to claim he wasn't responsible for empowering Hitler. It was an uphill battle; besides his part in getting Hitler appointed, Papen was briefly his vice-chancellor, and as a diplomat, he helped to enable the annexation of Austria and worked to bolster Germany's cause during World War II. He was found guilty at Nuremberg, but his sentence was only eight years, and it was overturned on appeal. A wealthy man, he regained his property and wrote his excusatory memoirs. When he died in 1969, his body was buried in his birthplace of Kleinglattbach in Prussia.

Heydrich was buried in a military cemetery

Given the warped morality of the Nazi regime, it's difficult to know if Hitler intended a reprimand or a compliment when he dubbed Reinhard Heydrich "the man with the iron heart." The BBC reported that others in the Nazi command called him "the butcher." He earned both monikers as Heinrich Himmler's chief lieutenant in the SS, as the head of the Gestapo, and as the brutal Nazi overlord of Bohemia and Moravia. Heydrich purged political opponents, was instrumental in planning Kristallnacht, and aided Himmler in drawing up the plans for the Holocaust. Even among the Nazi high command, he stands out as a particularly dark figure.

When he was assigned to govern Bohemia and Moravia in 1941, Heydrich achieved "pacification" by killing hundreds of people, according to the Holocaust Encyclopedia. By his command, some 34,000 German, Austrian, and Czech Jews were herded into the Lodz ghetto and other detainment centers. He bought off citizens with high wages and benefits. By the following year, he felt confident enough in his control over the Czech lands that he drove around in an open vehicle. Such lax security played into the Czech resistance's hands. On May 27, British-trained agents rolled a grenade under his car. Heydrich escaped total obliteration, but infections from shrapnel did him in days later.

Hitler himself attended Heydrich's state funeral, and he and Himmler were fulsome in their praise for the butcher. He was buried in the Invalid's Cemetery in Berlin. After the war, his grave was unmarked by Allied decree, but in 2019, someone managed to find and disturb it, though Heydrich's remains were intact.