Hitler's Disturbing Downward Spiral Explained

For millennia, the greatest minds have tried to find an answer to one of life's fundamental questions: Are people born evil, or do they become so due to their environment? This is commonly known as the "nature versus nurture" debate. Philosophers, theologists, psychologists, and more have given the subject a great deal of attention down the centuries, and today the scientific picture is nuanced, with both hereditary and environmental factors believed to influence how human beings develop moral or immoral behavior and impulses.

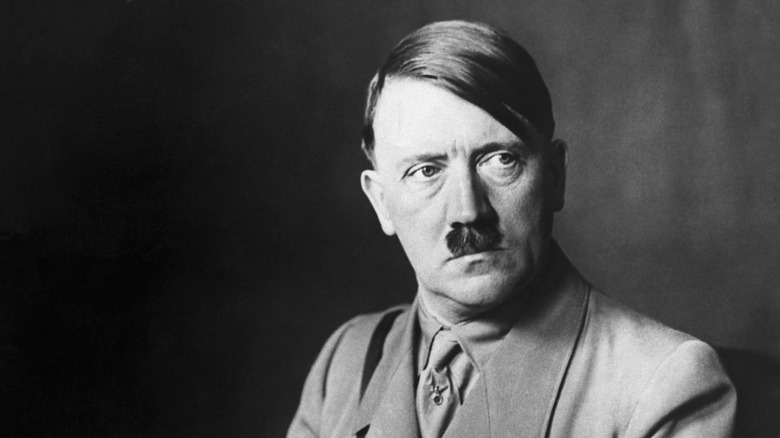

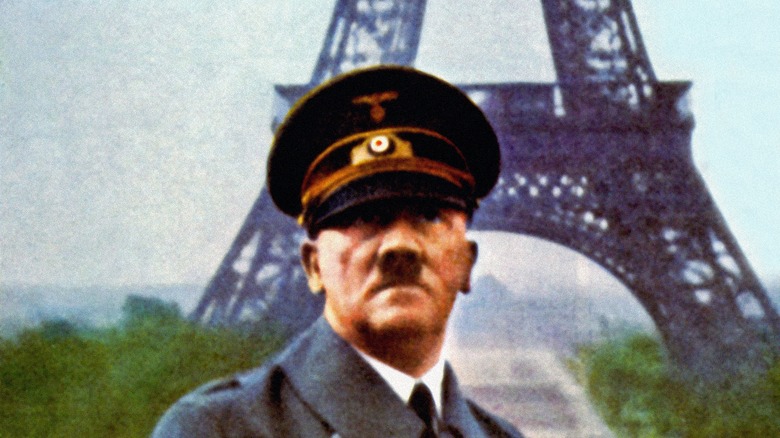

Things get complicated when thinking about the most reviled people in history, such as Adolf Hitler, the Führer (or leader) of the Third Reich in Nazi Germany. Under his orders, the atrocities of the Holocaust and other policies of persecution were responsible for an estimated 20 million murders, excluding the millions who lost their lives as a result of World War II. As studies have pointed out, such vast numbers are inherently dehumanizing, making it difficult for educators to adequately transmit the horrors of history.

Similarly, it is all too easy to forget that the crimes underpinning such widespread suffering were committed by humans, rather than the caricatured monsters that history often portrays them as. Indeed, Hitler's early life in Austria was not particularly abnormal, and there was little evidence that he would go on to commit acts of great evil once he gained political power. So what exactly happened?

His war experience left him twisted

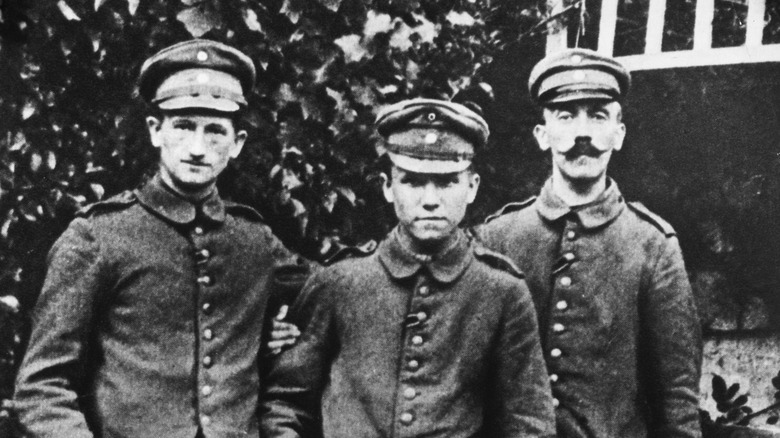

The early life of Adolf Hitler (pictured, right) was dominated by a major disappointment: His failure to fulfill his dream of becoming a recognized visual artist. As a young man he had relocated to Vienna, where he intended to enroll at the city's prestigious Academy of Fine Arts. However, against his own self-belief he was rejected, and he ended up eking out a living selling watercolor paintings to tourists and a small circle of regular customers.

His life took a more militaristic bent after he was traced to Munich for dodging the draft. Though he was initially rejected as too incompetent for combat, he enlisted as a volunteer in the German Army in 1914. Reportedly enthusiastic about the war effort, he was awarded two Iron Crosses and was wounded multiple times. Notably, a mustard gas injury left him temporarily blind and hospitalized, leaving him in the hospital when the war ended. In his memoir "Mein Kampf," he described the moment as pivotal to his political awakening and turn toward the kind of virulent nationalism that would later underpin the mass genocide orchestrated by the Third Reich. Some historians, however, believe that he centered this incident around the "awakening" narrative later in life, during the writing of his infamous work.

He was horrified by the Treaty of Versailles

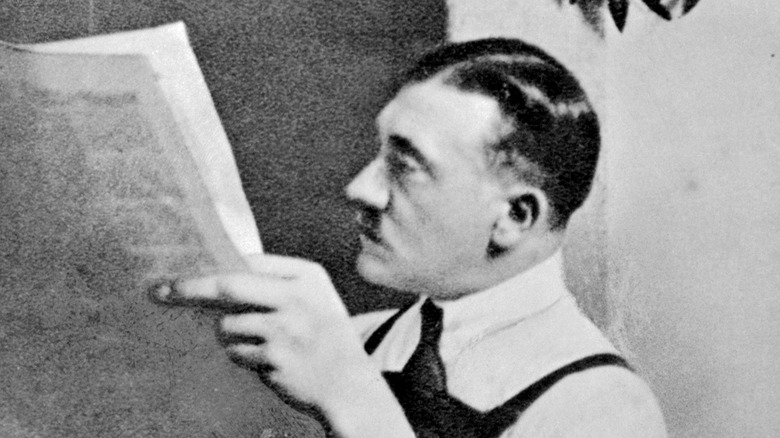

Adolf Hitler was convinced that propaganda was largely to blame for Germany's defeat in World War I. As an army enlistee, he felt betrayed by the country he sought to glorify. Further humiliations to the nation were to follow, which would shape Hitler's twisted political outlook and worldview that claimed Germany was under threat from within and without.

Like millions of people living in Germany at the time, he was affected by the economic collapse that resulted from the end of World War I, which was catastrophic for the country and led to widespread suffering. First came the Treaty of Versailles, an international agreement that many Germans saw to be unnecessarily cruel to the nation as it recoiled from the loss of the war. Hitler was no different. Per The Avalon Project, in a 1923 Munich speech he said the treaty "was made in order to bring twenty million Germans to their deaths, and to ruin the German nation." His rejection of the terms of the treaty became foundational to his political identity and the principles of his "German Workers' Party in the 1920s, the precursor to the Nazi Party. His stance gained strength as Germany continued to suffer economic disasters, including hyperinflation, in its aftermath.

He found a scapegoat in German Jews

Adolf Hitler's paranoid nationalism went beyond villainizing the victors of World War I, who he claimed were purposefully undermining German prosperity. He and his party also focused on identifying targets within their own borders to make an enemy of, and they found an exploitable one in the country's Jewish communities. Prior to the Nazi's rise to power, an Echos & Reflections report says they numbered more than half a million people, or around 0.8% of the German population.

In "Mein Kampf," Hitler claims that his antisemitic beliefs first came to the fore while he was attempting to live as an artist in Vienna, and frames his hatred as the result of some long intellectual journey. Historians now believe that these claims are bogus — part of the propaganda he used to come to power. His claims that antisemitism was rife among his comrades in the German Army in World War I have also been challenged. However, it is commonly held that Hitler was introduced to antisemitic ideas through several notorious German politicians. It is also believed that his purposeful scapegoating of Jews — who he said were directly responsible for Germany's post-World War I economic and societal malaise — tapped into a long history of persecution of the ethnoreligious group in Europe and beyond.

The death of his niece left him devastated

Adolf Hitler lived through a number of losses in his early life. Most notably, his parents both died when the future fascist was still in his teens. However, another death in the 1930s reportedly shook Hitler to his core: That of his half-niece, Geli Raubal.

Hitler was reportedly devoted to his half-niece, whose beauty was legendary and who was said to have been one of the great loves of Hitler's life. Little is known definitively about the exact nature of their relationship, and it remains a subject of much debate among historians. What is known, however, is that on September 19, 1931, Raubal was found dead in Hitler's Munich apartment, having apparently shot herself in the chest with her half-uncle's gun. The death is recorded among most mainstream historians as suicide, countering some fringe accounts that claim she was in fact murdered, perhaps at Hitler's behest.

Whatever the exact circumstances of Raubal's death, historians have also been at pains to try and pin down the effect it may have had on the future Führer. Some have suggested that Hitler went into an intense depressive period after her death. He was allegedly on the brink of giving up politics before a women present at a rally the night of Raubal's funeral made him even more politically strident. "Hitler" biographer Ian Kershaw disagrees, however, writing: "History would have been no different had Geli Raubal survived."

Experts believe Hitler wasn't significantly mentally ill

It is tempting to convince ourselves that the worldview Adolf Hitler espoused, the hate he wantonly unleashed into the world, and the genocidal results of his Third Reich policies are the symptoms of mental illness, expressing themselves through political power. Indeed, "Hitler was a madman" has been a mainstream belief in the Western world for almost a century at this point. But while we may cast around for details in Hitler's personal life or career history that point to the horrors he would later commit, experts now believe that attempts to see his crimes through the prism of mental illness are unfounded.

Psychologists have noted that Hitler was dominated in his early life by his father, and have claimed that he later developed a narcissistic personality as a result of the emotional wounds he experienced in his childhood and adolescence. But many people suffer while young without becoming virulent antisemites or expansionist fascists. Instead, the disturbing truth is that Hitler committed his crimes in a state of comparative mental acuity, and believed his choices were morally justified. "Hitler's crimes and errors were not caused by illness," concluded Dr. Fritz Redlich in his book "Hitler: Diagnosis of a Destructive Prophet." More disturbing still, Hitler's crimes were not committed by him alone, but were the result of his having indoctrinated huge swaths of the German population to believe his lies and view the world in his way. The phenomenon raises questions that we still struggle to answer today.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.