The Most Amazing Historical Discoveries Of 2019

With thousands of years of building, pillaging, fighting, and discovering already behind us, and bazillions of tons of dirt under our feet, there's still a lot about the story of homo sapiens that's waiting to be discovered. Shipwrecks lie far beneath the surface of the waves, ancient settlements are still hidden away under new cities, remains of ancient people lie in as-yet-undiscovered caves—we will probably get to the end of human history long before we've managed to uncover everything there is to know about the beginning of human history.

We're working on it, though. There's no shortage of curious explorers who are determined to find out everything there is to know about the past, and every year, archaeologists, historians, and kindergartners make startling discoveries that change the things we know or add to what we know in profound ways. Here are a few of the most amazing things we've discovered about our own history just since the beginning of 2019. And yes, we said "kindergartners."

We've been building artificial islands since before we knew how to write

There are hundreds of small islands in the lochs (lakes) of Scotland, and they're not natural. According to LiveScience, most scholars believed the islands were made during the iron age, which would make them roughly 2,800 years old. But a study published in Antiquity in the late spring of 2019 says they're actually much, much older than that—Neolithic people built them around 5,600 years ago.

The islands are made out of boulders, clay, and timber and are called "crannogs." One even includes a stone causeway that leads back to shore. Divers found Neolithic pottery fragments on the lake floor near some of the islands, which led researchers to guess that the crannogs were much older than originally thought. To confirm their theory, two archaeologists looked at crannogs in Loch Arnish, Loch Bhorgastail, and Loch Langabhat and used radiocarbon dating to determine that the crannogs were built sometime between 3640 and 3360 BC. The pot fragments likely got into the lakes because they were dropped there deliberately, perhaps ritualistically.

So far, just 10 percent of Scotland's crannogs have been radiocarbon dated, so it's possible some of them are even older than those in the first three lakes studied. Very cool.

Kindergartners discovered a burial site that was used for 2,000 years

Most kindergartners, if they're lucky, will find pennies or forgotten matchbox cars in the school play area. Most of the time, it will be gum wrappers or cigarette butts, but occasionally fortune favors those between the ages of five and six. Like back in 2006, when kids in the town of Saint-Laurent-Medoc, France, were digging around in their school's playground when they found bits of bone. Fortunately, they were just bone fragments, so it's not like these poor kids had to have nightmares for the next 10 years about the skeletons that were lingering just below the swing sets or anything.

It wasn't until 2019 that archaeologists learned just how significant the discovery actually was. According to LiveScience, excavation revealed that there were at least 20 adults and 10 children buried on the site, a mere 1.6 feet beneath the surface. Radiocarbon dating of the remains revealed that the site was used for burials for at least 2,000 years, beginning in 3600 BC and ending in 1250 BC.

The author of a study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science said the site was not "obvious or prestigious," so no one is sure what it is about the place that compelled people to bury their dead there for so many years. Maybe it had some sort of magical quality, you know, the sort of thing that compels kindergartners to go digging for buried treasure.

A human cousin that was even smaller than hobbits

In 2003, the world was astonished by the discovery of the actual remains of Frodo and Bilbo. Just kidding. Frodo and Bilbo are still permanent residents of Middle Earth, but there were once small humanoids living here on Real Earth who bore a remarkable resemblance to Tolkein's hobbits. Researchers even nicknamed them for the hairy-footed, short-statured, fictional humanoids—officially, they're called Homo floresiensis, but unofficially they're called "Hobbits."

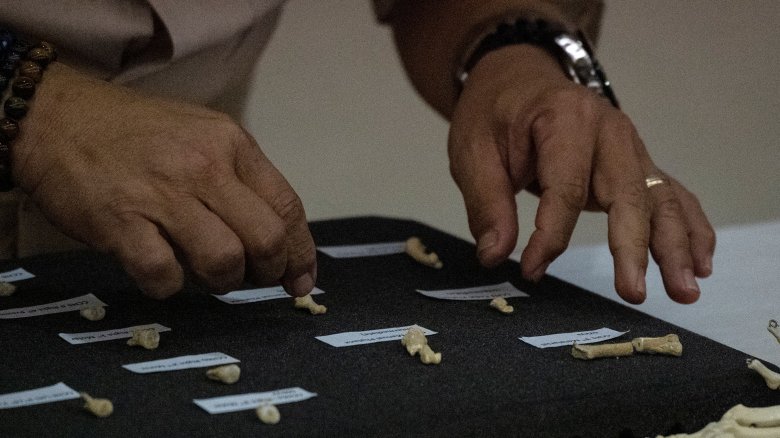

In April of 2019, a paper published in Nature announced the discovery of another ancient human species called Homo luzonensis. This hominin lived 50,000 to 67,000 years ago on the island of Luzon and was even smaller than Homo floresiensis. Researchers identified the new species based on seven teeth and six bones, which came from at least three individuals. The bones had features associated with both advanced and ancient human characteristics—the teeth resemble those of modern humans, while the foot bones look more like australopithecines.

Before the recent discoveries of hominins in the Philippines, researchers thought that ancient humans were limited by oceanic barriers—Luzon, in particular, seemed like it would be inaccessible to creatures that didn't possess boats. So finding the remains of such ancient humans there is pretty remarkable.

Yes, that Viking warrior really was a woman

If you watch History Channel's Vikings, you know the shieldmaidens were totally a thing. Actually, they probably weren't a thing, but still, Lagertha is awesome so just shut up already.

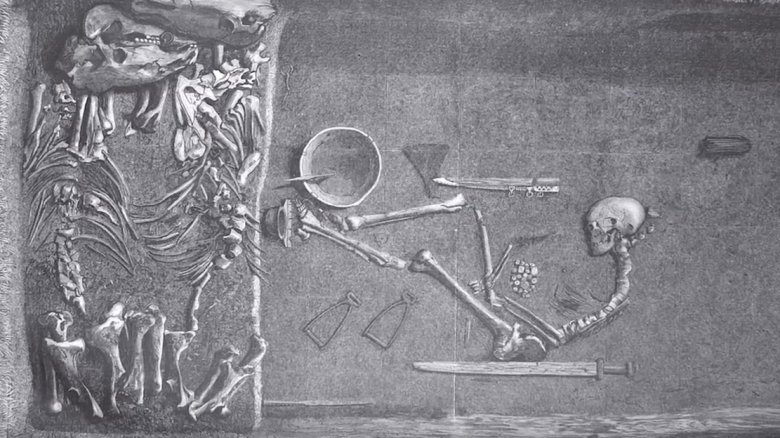

There is some evidence, though, that there might have been occasional female Viking warriors, though researchers are still reluctant to say that they were any more common than female warriors in other cultures. One Viking grave became famous in 2017 when researchers announced they'd identified the occupant as a woman—and not just any woman, but one who was buried like a warrior, with weapons and two horses.

According to LiveScience, the announcement was met with skepticism, because for some reason, even after six seasons of Vikings, it's still difficult for people to comprehend that women might be capable soldiers. So in 2019, researchers set out to answer everyone's questions about the grave's occupant: Did they test the correct bones? Yes. Was there a second body in the grave? No. Did genetic analysis confirm the person's gender? Yes. Was she really a warrior? Well, there are certainly some possible alternate explanations for the burial that would exclude her as a warrior—maybe she was just a symbolic warrior, for example, or maybe the items in the grave belonged not to her but to a son or husband. The logical conclusion, though, is the obvious one—she was buried with a warrior's possessions because she was a warrior. Lagertha lives. Err, once lived.

America's last known slave ship was found at the bottom of the ocean

The discovery of the Clotilda off the shore of Mobile, Alabama was a grim and somber find, but it was also an important one, because for decades there were people who denied that the Clotilda's history was anything more than a story. The Clotilda was America's last slave ship—in July of 1860, it brought 110 Africans to Alabama, during a time when it was actually illegal to import African slaves to America. And it wasn't just a misdemeanor, either. The crime was considered piracy and was punishable by death.

According to National Geographic, Clotilda's captain took the job after a wealthy landowner named Timothy Meaher made a bet with some local businessmen that he could smuggle Africans into the state without getting caught. After the ship delivered its human cargo, the captain burned and sank it to hide evidence of the crime. The ship remained disappeared until it was discovered in the waters off Twelvemile Island in the Mobile Tensaw Delta. The find was announced in May of 2019.

The ship, which showed signs of having been burned, was confirmed to be the Clotilda using known data about the ship, like its size, dimensions, and the materials it was made from. The find was significant not just because of historical interest, but also because it was vindication for all the people whose ancestors arrived aboard America's last slave ship.

Climate change may have brought down the Byzantine Empire

By now everyone except a select few naysayers is aware that climate change is going to kill us all. Even the naysayers are pretty sure it's going to happen, it's just that they're all still saying "nay." But this isn't the first time in the planet's history that climate change has had a negative impact on the world's human population.

According to Discover, there is new evidence that a "little ice age" might have brought down the Byzantine Empire. In 536 AD, a series of volcanic eruptions sent enough ash into the atmosphere to temporarily dim the sun, but until recently archaeologists had a difficult time finding evidence of what happened in human settlements during this event. Then they realized they could sift through ancient garbage heaps, which lay pretty much undisturbed over the centuries, even as cities were torn down and rebuilt.

In March of 2019, a study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences revealed that trash accumulation in the Byzantine city of Elusa pretty much ceased after the middle of the sixth century. That coincides with all of that volcanic activity and predates the Islamic conquest, which historians have long blamed for the end of the Byzantine Empire. Climate change alone was probably not enough to cause the fall of Elusa, but it's likely that the Little Ice Age impacted trade severely enough to convince the city's occupants to find a living elsewhere.

Alexander the Great may have died from Guillain-Barre Syndrome

The life of Alexander the Great is fairly well-documented, but the thing about death in antiquity is that we can never really be sure what the cause was. Diseases went by different names, and sometimes the historical descriptions were vague. We can't always find the evidence in a body, either, even when one exists. So scientists are often left wondering what brought down a king or an emperor or some other important historical figure.

According to Science Daily, Alexander the Great's death has been attributed to causes as varied as alcoholism, murder, or simple infection. But a clinician and researcher named Katherine Hall thinks she's finally solved the mystery—she thinks it was a quite modern-sounding illness known today as Guillain-Barre Syndrome.

What's especially bizarre about historical accounts of Alexander's death is the claim that his body failed to decompose until after he'd been dead for six days. The Romans thought that meant he was a god (because of course they did), but Hall thinks it's evidence that Alexander was in a coma. In those days, doctors used the absence of breath to decide if someone was dead—no one would have taken Alexander's pulse, which means its possible that he was in a death-like state but not technically deceased. And his other symptoms match Guillain-Barre Syndrome: The fever and abdominal pain, the progressive paralysis, and the fact that he was completely lucid until the moment of his death. Wow.

Neanderthals and Denisovans were pals

We've all mostly come to accept the idea that different species of early humans once shared our planet and occasionally shared genes, too. But it also seems likely that we didn't really get along—after all, for a long time the prevailing theory was that human beings wiped out Neanderthals (though that theory has been mostly replaced by the more boring theory that the species was in decline before humans even arrived in Europe).

But now, LiveScience says that it looks like other human species coexisted quite nicely, including Neanderthals and Denisovans. In 2019, researchers announced the discovery of a Siberian cave that contained evidence of both Neanderthal and Denisovan occupation—Neanderthals lived there 190,000 to 100,000 years ago, while the Denisovans were there from 200,000 to 50,000 years ago. It's not the first time that evidence of that kind of coexistence has been found, either. In 2018, researchers found a bone fragment of a girl who had a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father.

It's not known if early humans also lived there, though there is at least one bone that could be from a homo sapien (scientists were unable to recover any DNA from it) and there are also tools and ornaments that could be human in origin. So basically, the cave was just a big paleolithic melting pot. If only Neanderthals and Denisovans still existed, maybe we could learn something about how to get along. Ha. Ha.

The tomb of an Aztec king ... maybe

The Aztecs were a fascinating bunch, but they were also really, really terrifying. It wasn't just the fact that they were fierce warriors, either, it was the whole war sacrifice thing, which is pretty much the epitome of terrifying.

According to Reuters, in March of 2019 archaeologists discovered a "trove" of Aztec sacrifices right underneath Mexico City, which included a boy dressed as the Aztec god of war and a jaguar that was dressed like a warrior. Yes, an actual jaguar. There were other objects, too, but the most exciting part of this discovery wasn't the objects themselves but their placement, because the way they were arranged matches historical accounts of royal burials. Among the finds was also a roseate spoonbill, which was thought to represent the descent of a king or warrior's spirit into the underworld. These details have led archaeologists to believe that they might be close to discovering the tomb of an Aztec king—something that archaeologists have been unsuccessfully searching for for decades.

The artifacts were found at the base of the Templo Mayor, an Aztec temple that was razed after the Spanish conquest in 1521. If the archaeologists' hunch is right, though, they're not likely to find a royal skeleton in the royal tomb—historical accounts of royal burials say the king was cremated and interred with the hearts of the sacrificed slaves, which sounds like a gross way to spend eternity but who are we to judge?

Some weird boats that came right out of the ancient history books

Ancient historians were forever describing stuff that may or may not have existed, like the Hanging Gardens of Babylon—said to be one of the seven wonders of the ancient world but may not have actually been a thing. So it's pretty cool when archaeologists find an artifact that actually seems to correspond to something in the historical record, which is what happened in 2019 when a strange shipwreck was discovered at the bottom of the Nile.

According to The Guardian, in the fifth century BC, the Greek historian Herodotus described some odd-looking riverboats he saw while visiting Egypt. Herodotus was so fascinated by these boats that he went on about them for 23 lines, but because no one had ever found an example of such a thing modern historians weren't sure if they should believe him.

Then, 2,469 years later, archaeologists found an example of exactly the boat Herodotus described at the bottom of the Nile near the sunken port city of Thonis-Heracleion. The boat appears to have been assembled in exactly the way that Herodotus said it would be, with planks held together by long tenon-ribs that were fastened with pegs. It's a type of construction not previously seen anywhere in the world, and it proves that Herodotus, at least, wasn't just making stuff up for the fun of it. Though, why would he? Maybe we should believe in the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, too.

The tomb of some wealthy ... pet owners?

Everyone knows the Egyptians were into mummifying things. They mummified kings, they mummified cats, they mummified random other people. It was gross and weird and really freaking elaborate, but every culture has to have its thing.

According to Al Jazeera, a huge collection of mummified corpses was uncovered recently in an elaborately painted tomb near the town of Sohag, Egypt. Only a few of the mummies are human—the rest are animals, including cats, dogs, falcons, and mice. Around 50 animals in total were buried there, along with a woman and a boy between the ages of 12 and 14. There are also two stone coffins meant for the tomb's owner and his wife. The tomb has very well-preserved wall paintings, which depict funeral processions and images of the tomb's occupant and his family.

So what's the deal with all the mummified animals? It's not odd to find mummified pets in Egyptian tombs—the ancient Egyptians sometimes mummified their animals so they would have companions in the afterlife. Mice, though? Professor of Egyptology Salima Ikram told LiveScience that the animals were probably "votive offerings," placed in the tomb long after the human burial. They may not have had anything to do with the tomb's occupants at all, so if you were just now entertaining the notion of a pair of ancient animal lovers headed to the underworld in a chariot pulled by mice, well, sorry to disappoint.

An undisturbed Roman shipwreck

If you've seen images of the Titanic rusting away deep in the North Atlantic, it's kind of hard to imagine that there might be ships from thousands of years ago still sitting undisturbed at the bottom of the ocean, waiting for some diver to come along and discover their secrets. According to the Cyprus Department of Antiquities, though, archaeologists found just such a thing off the coast of Protaras, Cyprus, and they say it's the first undisturbed Roman shipwreck ever found in the area.

Now granted, it sounds like most of what's left of the ship is its cargo of amphorae, which are ancient jugs with handles and narrow necks that once held liquids like oil and wine. The amphorae are thought to have originated in Syria or ancient Turkey, and it's hoped that the wreckage will help historians understand how goods were moved between Cyprus and the other Roman provinces in the eastern Mediterranean.