The Most Disturbing Stories About Hell In The Bible

So hell, right? It's that fiery place where all the bad people go. It's got some torture, some torment of the eternal variety, some demons leaning on their pitchforks while taking a water-cooler break from flaying the souls of the damned, and so forth. For a place so prominent in Abrahamic religions — or state of being, depending on your interpretation — there must be some pretty messed-up stories about it in the Good Book, yes? So long as we remember that "hell" doesn't exist in the Bible. "Hell" is a fusion of literary, mythological, and artistic influences that didn't really cohere until Enlightenment Europe (1685 to 1815 C.E.), in no small thanks to artwork.

The word "hell" made its way into English via Old Norse "hel" and a shared cultural ancestry referenced by early Christian missionaries to Anglo-Saxon peoples. When the Bible was eventually translated into English, "hell" got used for a variety of translated words — like "Hades" and "Tartarus" in the New Testament — that borrowed from Greek. The Old Testament, meanwhile, used "Sheol" to connote a physical pit in the ground where people are buried and described the burning valley of "Gehenna." Non-canonical Christian texts like the 2nd-century "Apocalypse of Peter" also describe "hell" complete with a "Divine Comedy"-like jaunt through the underworld featuring ultra-specific punishments for different types of earthly acts (think Dante's "Divine Comedy"). All such references describe different places and concepts of the afterlife, and they all converged to create one singular vision of "hell." All of them are also disturbing in their own ways.

[Featured image by José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Sheol: the snare of the grave

Even though it sometimes gets badly translated as "hell," "Sheol" is best understood to mean "the grave" mentioned in Genesis 37 or "the realm of the dead below" in Deuteronomy 32. Mentioned 66 times in the Old Testament, Sheol has helped create our modern vision of hell, even though the Hebrew Bible has no firm conception of an afterlife. As the Jewish Virtual Library explains, Sheol was envisioned as a kind of a dark, shadowy realm under the surface of Earth, as a part of Hebrew cosmology. It isn't hard to see how this heritage influenced the evolution of hell over time, especially because Christianity grew out from Judaism.

But Sheol is still eerie in its own right, especially because Hebrew writers tend to describe it in such dire, terrifying ways. 2 Samuel 22 says, "The cords of the grave coiled around me; the snares of death confronted me." Psalm 18 echoes this sentiment, saying, "The cords of death entangled me; the torrents of destruction overwhelmed me." Psalm 141 also says, "As one plows and breaks up the earth, so our bones have been scattered at the mouth of the grave." In these passages Sheol sounds like a physical place. But passages like 1 Samuel 28 — featuring a medium summoning a spirit — imply that Sheol is populated by intangible beings. This vagueness, and the lack of certainty it implies about life after death, is perhaps more frightening than anything specific.

Gehenna: sacrificing children to flames

Gehenna gives us our first piece of the hell puzzle with a familiar element: suffering and purification by fire. Gehenna is a real, geographical place — the Valley of Hinnom, via the Greek translation in the New Testament. In the Old Testament, Hinnom was where Canaanite worshippers of the god Moloch engaged in child sacrifice by fire. Old Testament passages like 2 Chronicles 28 read, "He burned sacrifices in the Valley of Ben Hinnom and sacrificed his children in the fire." Travelers can even visit this area nowadays in Jerusalem, sandwiched between the Old City and Mt. Zion.

So when New Testament writers reference Gehenna, they had this shared history in mind. They used it as a shorthand for the damnation, hell, hellfire, etc., that follows separation from God or defiance of God's ways. Matthew 5 says, "It is better for you to lose one part of your body than for your whole body to be thrown into hell." Along these same lines, Matthew 18 says, "It is better for you to enter life maimed or crippled than to have two hands or two feet and be thrown into eternal fire." Meanwhile, James 5 says, "The tongue also is a fire ... It corrupts the whole body, sets the whole course of one's life on fire, and is itself set on fire by hell." All in all, it's not too hard to see how a site of child sacrifice became equated with an inferno of godly punishment.

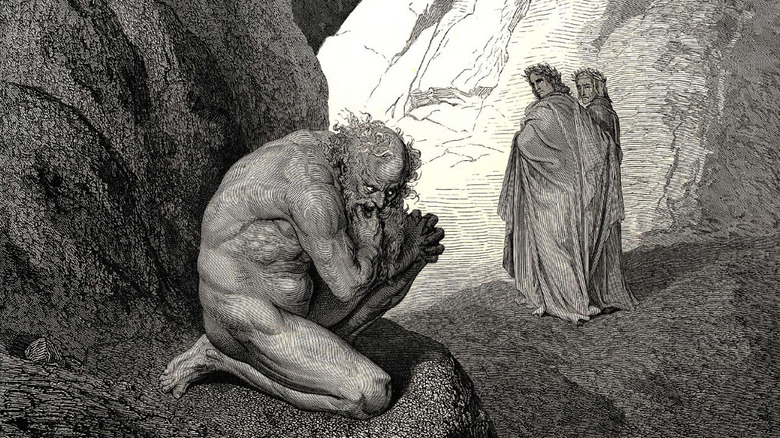

Tartarus: prison of aimless waiting

Next we come to one of the more curious words that was translated into the English "hell" and helped form our modern impression of the place: Tartarus. Folks familiar with Greek mythology will recognize Tartarus as one of the two grim components of the Greek underworld Hades, opposite to Elysium. Similar in cosmology to the Hebrew Sheol, Tartarus didn't start as the realm of the dead but as a deep, subterranean prison for the titans when the gods of Olympus overthrew them. It's basically a pit opposite to the sky and surrounded by "gates of iron and a brazen doorstone," as Theoi quotes Homer's "Iliad."

This is the tradition that New Testament writers were drawing on when they referenced Tartarus to describe their new religion, especially seeing as the collection of texts was first written in Koine Greek — the common Greek of the time. They went one step further, though, and equated the Greek titans to fallen heavenly angels, with Tartarus being the holding cell where they'd wait for the much-anticipated end of days. 2 Peter 2 reads, "For if God did not spare angels when they sinned, but sent them to hell, putting them in chains of darkness to be held for judgment." Similarly, Jude 1 says that these angels are "kept in darkness, bound with everlasting chains for judgment on the great Day." All in all, Tartarus comes across as an aimless limbo land, which for some might be more torturous than outright torture. But, it's also not for humans.

Hades: realm of disembodied souls

Biblical writers also used the Greek term "Hades" in their writings, which like every other term in this article sometimes got badly translated into "hell." To the ancient Greeks, Hades was the place of the dead. It was a misty, faded, grayed-out version of the world above — so yes, it was also underground. It was also a physical place where heroes like Orpheus, Odysseus, and Heracles actually visited. But despite being a physical place, it was also populated with souls. And so we come across the same spirit-body dichotomy that's long-characterized Judaism — and by extension, Christianity — and defined its theology.

As The Scriptures explains, when used by New Testament writers Hades more or less means, "the realm of disembodied souls." In 1 Corinthians 15, apostle and church founder Paul — a highly educated person who drew on traditions to make his point to Greek speakers — says of Jesus' redemptive power, "Where, O death, is your victory? Where, O death, is your sting?" Hades also shows up in Revelation 1 when Jesus says, "I am the Living One; I was dead, and now look, I am alive for ever and ever! And I hold the keys of death and Hades." Hades isn't described in detail very much in the New Testament, but Greek conceptions of the place are creepy enough: isolated, sad, gloomy, and filled with wandering souls. Sounds like hell, all right.

[Featured image by Gustave Dore via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

Lake of Fire: final place of eternal torment

Finally, we come to one more biblical place that often gets conflated with "hell:" the "Lake of Fire" described in Revelation, the final book of the Christian Bible that brings millennia of Jewish and Christian apocalyptic musings to a close. Talk of "fire" might conjure modern visions of "hell" as a fiery place, but like we've been saying this entire article: Hell doesn't exist in the Bible. When folks think of hell they're taking Sheol, Tartarus, Hades, and Gehenna — which all contributed to the vision of hell and got translated into English as "hell" — and mashing them into the Lake of Fire described in Revelation.

As Revelation 20 explains, no soul is hanging out in the Lake of Fire right now — whatever and wherever it is. As the familiar Christian tale goes, Jesus will come back to Earth, judge people, and toss unbelievers in the Lake of Fire. This is the "second death," the permanent destruction that frames other afterlives as temporary waiting rooms. Revelation 20 even says that Hades itself — the place of the disembodied dead — will be tossed into the Lake of Fire, presumably because it will no longer be needed. But despite fire being associated with physical pain, burning, agony, etc., 2 Thessalonians 1 describes existence in the Lake of Fire as "shut out from the presence of the Lord." Whatever that means is up to the imagination of the reader.