Strange Rules Soldiers Have To Follow During War

"War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it," wrote General William Tecumseh Sherman during the American Civil War. In 1864, during Sherman's March to the Sea, which was devastating to the Confederacy, Union Army troops marched deep into Georgia while pillaging farms, killing livestock, burning homes, and destroying the crops that fed locals as well as the Confederate army. This tactic helped hasten the end of the war, but it was devastating to the civilians who saw the war come to them without warning. However, even as General Sherman wrote those words, European nations were already working on what Sherman considered impossible: refining the rules of war to make it less cruel.

Sixteen nations met at the first Geneva Convention in 1864 to set ground rules to ensure that, even in wartime, injured soldiers would be cared for no matter what side they were on and that civilians would also be protected. With more conventions at Geneva, the Hague, Teheran, and other locations, those nations rewrote the rules to make sure people were still protected even as new technologies made war deadlier.

The result is the International Humanitarian Law, or IHL, the core components of which are signed by all 196 countries and which soldiers are bound to follow no matter where in the world they serve. Some rules — such as not wearing blue helmets — seem downright strange at first glance. Others — such as announcing your attack before you make it — seem counterproductive when your object is to win, yet the laws are all there for good reasons. Here are some of the strange-but-true rules soldiers must follow during war.

No pillaging for personal gain

Pillaging in wartime did not start with General Sherman and his men; it's as old as history itself. Enjoying the spoils of war was part of daily life for the Vikings. The Vandals, a Germanic tribe, were so notorious for looting and destroying Rome in A.D. 455 that the word vandalism is named after them. In Homer's Odyssey, Odysseus and his men attacked and pillaged the town of Ismarus on the island of Cicones and then took off in their ship, only to face the wrath of Zeus in the form of a lightning and windstorm.

These days, pillaging may not bring quite such swift supernatural justice, but it still brings consequences. Rule 52 of the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) takes a strict no pillaging stance. You may not wantonly destroy that which belongs to your enemy or take it for your own personal gain.

The key phrase here, though, is "personal gain." While taking souvenirs from the battlefield or from occupied lands is a war crime, it's a different story if you take supplies out of military necessity. According to the IHL reference Elements of Crime, in wartime it's okay to appropriate captured items out of dire need for the greater good and it only amounts to pillaging if you do it to personally enrich yourself.

No surprise attacks

This one may seem counterintuitive, but military forces have to give advanced warning for any planned attack. According to International Humanitarian Law (IHL) Rule 59, this has to do with protecting the safety of citizens who would otherwise get caught in the crossfire.

Advance notice gives civilians — noncombatants of all ages — time to find safe shelter or evacuate the targeted area. Furthermore, the rule stipulates that civilians can never be the object of attack, even if they don't evacuate when advised to. Therefore, soldiers are not allowed to use their warning as a threat that anyone left behind will be a potential target of military attack, and IHL Rule 16 explicitly requires soldiers to verify that their attacks are aimed at military targets. On the flip side, governments are required to avoid positioning their military bases in or near populated areas.

For those civilians who do evacuate, safe passage must be guaranteed, meaning the warring parties agree to suspend hostilities along the routes that people are escaping. Safe passages — or humanitarian corridors — can move in both directions, allowing the movement of essential supplies like food and water as well as aid workers and doctors into warzones. And speaking of doctors, hospitals are safe zones that soldiers are not allowed to attack, per IHL Rule 35. If no hospital building is available, it is possible for aid workers to set up "neutralized zones" to care for the sick and protect civilians, and military forces must also respect such zones.

Don't destroy farmland

It was a common tactic of ancient warfare to destroy crops and livestock to starve your enemy. Some ancient civilizations — the Greeks, Romans, and Persians, to name a few — took crop destruction a step further and supposedly sprinkled salt on their enemy's soil to ensure nothing ever grew there again. This practice still baffles historians today, considering how precious salt was in the ancient world, leading some to argue that victors were exaggerating their exploits, and that salting the earth happened less than it was recorded to. Whether myth or fact, "salting the fields" is not an acceptable act of war today, as destroying your enemy's farmland, either temporarily or long term, is now a war crime.

International treaties make it clear that warring forces should never destroy the things that local people depend on to live, whether it be a water source, crops, or livestock. Therefore, farms should be avoided as battlefields, according to International Humanitarian Rule (IHR) 54. If that doesn't make it clear enough, there is a separate IHR Rule (number 53) forbidding the use of starvation as a weapon. This means that not only do soldiers have to preserve farms and water sources, but they also can't block food from reaching civilians.

This is particularly important if soldiers lay siege to a city or other area populated by civilians. The attacking forces cannot force civilians to stay there and face starvation as supplies diminish. Instead, as with any attack, soldiers must allow safe passage for civilians to safely escape the area under siege.

No blue helmets

Armed soldiers can never wear light blue helmets, according to International Humanitarian Law (IHL) Rule 65. This seemingly arbitrary rule that limits armies' color choice has a good reason: United Nations (UN) Peacekeepers wear light blue helmets. UN Peacekeepers (shown above) are deployed to warring countries to help promote peace through disarmament, assist with free elections, and generally keep non-combatants safe. For a soldier, posing as a peacekeeper to gain trust — if your motive is really to kill — is a war crime known as perfidy. The same goes for disguising a military vehicle with the well-known symbols of the Red Cross or Red Crescent, which represent the International Committee of the Red Cross and are associated with the supply of medical aid in wars and natural disasters.

Another reason to dress the part of a soldier is that the failure to do so will revoke your right to prisoner-of-war status should you get caught by the enemy, according to IHL Rule 106. In order to qualify for the protections afforded to prisoners of war, soldiers must differentiate themselves from civilians by wearing approved army uniforms and carrying their weapons openly. Soldiers in disguise will be tried as spies when they are caught.

Insults and threats can be considered inhumane

In wartime, International Human Law (IHL) has guidelines for soldiers on how to treat their enemies, and one well-known example is that if your enemy lays down their weapon, even in the heat of battle, you can't kill them. As it turns out, according to according to IHL Rule 46, this also extends to threats. To say that there will be "no quarter given," which in military-speak means you'll leave no survivors, is a war crime. In other words, not only is it illegal to kill an enemy who can't or won't fight back, it is also illegal to say you will.

Soldiers are required to give quarter to enemies who have stopped fighting for any reason, be it injury, surrender, or even shipwreck. Instead of shooting or threatening to shoot, the legal obligation is to hold a non-fighting foe as a prisoner of war, who is then entitled to certain rights, such as medical care. Indeed, it was partly the belief that all injured soldiers deserved medical care (rather than being abandoned to suffer) that inspired the first Geneva Convention.

Once in custody, a prisoner of war does not have a right to due process but does have a right to basic food, shelter, and humane treatment. And that last one is important, since insults and threats are considered inhumane treatment and are therefore not allowed. Such language extends to the religious practices of prisoners of war, which must be respected and not used as grounds for derogatory treatment, verbal or otherwise.

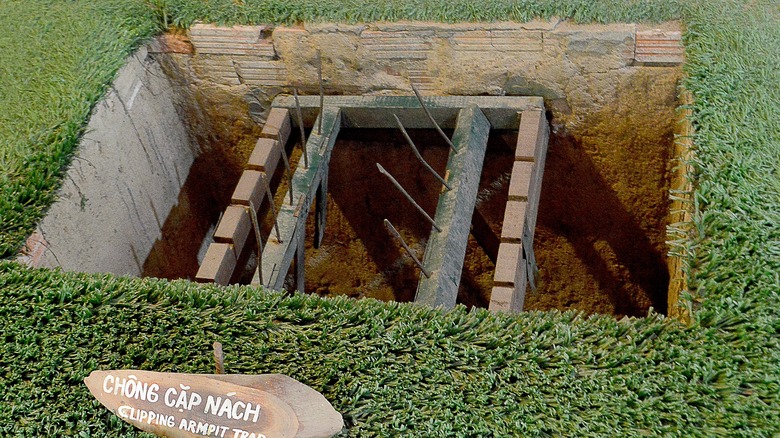

Don't set that booby trap

It may have worked in "Home Alone," but setting a booby trap is a real war crime. For one thing, it makes a harmless action (such as opening a door) potentially deadly. It is also an indiscriminate weapon, meaning it targets any person who happens along it, whether that be a civilian or an enemy combatant. In any military operation, soldiers are required to discriminate between enemy combatants and civilians, directing any attacks toward the former and not the latter. If the weapon itself is not focused enough to fulfill that requirement, it can't be used.

Under the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) Rule 71, a booby trap falls under a very large umbrella category of indiscriminate weapons. Those include landmines, cluster bombs, scud missiles, chemical weapons, nuclear bombs, and biological weapons that can include novel and lesser-known insect warfare. And if that was not clear enough, IHL Rule 80 deals specifically with booby traps, prohibiting their use in culturally significant locations such as graveyards or by using objects that would cause harm to civilians, like children's toys.

Make sure your bullets meet regulation

Hollow-tip or "dumdum" bullets, as they were called in British armies in the 19th century, are now forbidden in warfare, according to International Humanitarian Law (IHL) Rule 77. Such bullets expand or flatten when lodged inside a human body, causing more suffering and making it harder to remove than a standard bullet. Likewise, bullets made of plastic or other material that would be undetectable by X-ray are also forbidden because they are harder for medical providers to remove. And poison-tipped bullets are most certainly out of the question.

However, the banning of hollow-tipped bullets is not universal. The United States never signed the 1899 Hague Declaration that originally banned expanding bullets internationally. Furthermore, the U.S. Department of Defense has taken the position that there are instances — namely counter-terrorism operations — in which hollow-tipped bullets can be used by the U.S. military. For their own assessment of which weapons to ban, the U.S. Department of Defense asks: is the suffering it causes disproportionate to its advantage in warfare? If the weapon is crucial to the mission, then the suffering it causes is deemed necessary.

Always be on time

International treaties aside, there are more specific rules the U.S. military has for their own soldiers to follow in wartime, all of which are written up in the Uniform Code of Military Justice, or UCMJ. Article 86 of the UCMJ deals with what most of us call tardiness: not being at your appointed post at the designated time. The U.S. military takes a far sterner view of poor timekeeping and considers such tardiness as absence without leave, otherwise known as being AWOL. This can have dire consequences, especially if you miss your transport, and you will also be considered AWOL if you leave your post early without permission.

Keep in mind, though, that in wartime anything can happen. Perhaps you were attacked on your way to report for duty and were knocked unconscious. If you are accused of being AWOL but can prove that you were physically unable to report for reasons beyond your control, you can be excused as long as you reported for duty as soon as you could. On the other extreme, remain AWOL too long and you will be a deserter as described in UCMJ Article 85. A more serious offense, desertion may take the form of leaving your post with the intent to stay away permanently or enlisting in another army while still enlisted in the U.S. military.

No dawdling

"I'll wait for you, and should I fall behind, wait for me," sang Bruce Springsteen in his 1992 hit song, "If I Should Fall Behind." It makes for a sweet lyric, but such a sentiment would get you in trouble in the U.S. military. Falling behind or straggling is prohibited by the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) Article 134. In wartime, lagging behind your group could prove disastrous and even harm the military's reputation. The offense carries harsh penalties: up to three months in confinement (or "in the brig," as it's called).

Articles 133 and 134 are known as general articles because they include a wide array of offenses that could tarnish the military's reputation or prove unbecoming of an officer. Other actions that could get you in trouble under these two articles are adultery, public drunkenness, cheating on a test, wearing insignia you didn't earn, threatening another service member, failing to pay a loan, violating parole, breaking medical quarantine, and using foul language. Whether it be figuratively or literally, dragging your heels is a big no-no in the U.S. military.

Don't play sick

We all remember that scene in "E.T." where Elliot held his thermometer up to an incandescent light bulb to heat it up, just enough for his mother to think he had a fever. Though Elliot had his reasons to feign illness, that act would have gotten him court-martialed in the U.S. military. The official term for this, malingering, is prohibited by Article 83 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ).

Malingering is a blanket term that could mean feigning an injury or an illness or even simply exaggerating real symptoms to avoid duty. A particularly harmful form of malingering is by deliberately causing yourself to become injured or sick. For example, refusing to eat is malingering, because it could lead to you being too weak to work, and hunger strikes are certainly not allowed in the military. Active service members that try to pull a sicky may find themselves dishonorably discharged or even confined to prison, with the sentences running into years if the offence takes place in a warzone.

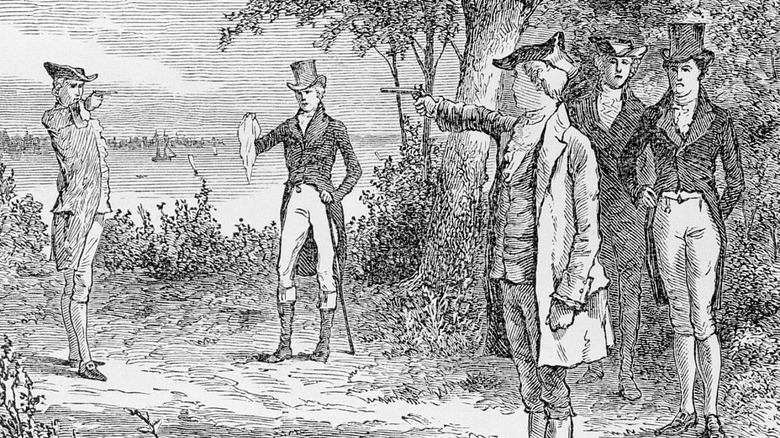

No dueling

Dueling may be still legal in some U.S. states, but it has long since been illegal in the U.S. military. However, that was not always the case. Before the American Civil War, duels were so common among service members that twice as many Navy officers died from duals than from combat. After the bloodshed of the Civil War, duels lost their allure. Now they are so illegal in the military, you'll get in trouble even if your duel does not involve firearms.

A fist fight between two people is a dual, as far as the military is concerned. You don't even have to be the one directly involved, as you can get in trouble merely for encouraging others to dual, and if you hear of a duel happening, you will also run afoul of military law if you keep it to yourself rather than tell a commander. In Article 114 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), dueling is listed among other reckless endangerment offenses, including the unauthorized discharging of a weapon and concealing a firearm.