How The Plane Crews Reacted To Bombing Hiroshima And Nagasaki

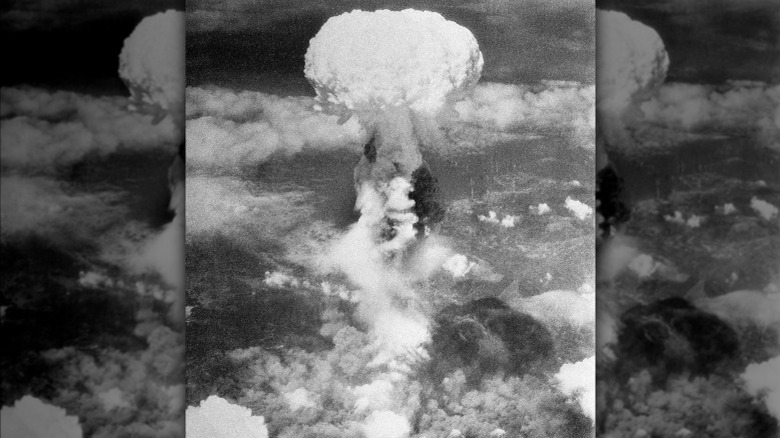

On the morning of August 6, 1945, the crew of the Enola Gay, a stripped-down B-29 Superfortress, and six other bombers left the island of Tinian. The Enola Gay carried a brand new weapon, an atomic bomb nicknamed Little Boy. The planes headed towards Japan, specifically the city of Hiroshima, home to about 350,000 people. At 8:15 a.m. Hiroshima time, the Enola Gay dropped its payload, and 43 seconds later, Little Boy exploded over Hiroshima.

From the plane, Hiroshima was blanketed in a thick cloud of black smoke. Below, the city they'd bombed lay in utter desolation. An estimated 80,000 people died instantly with thousands of more dying from their wounds and from radiation sickness. Three days later, another U.S. bomber, Bockscar, dropped a second atomic bomb dubbed Fat Man on Nagasaki. This Japanese city suffered a similar fate to Hiroshima. None of the bomber crews expressed remorse for what they'd done, believing it was necessary to end the war. The day after the bombing of Nagasaki, Japan offered to surrender.

General Paul Tibbets never lost sleep

General Paul Tibbets, who named the B-29 Enola Gay after his mother, and piloted the plane, played a vital part in the mission to drop an atomic bomb on Hiroshima. He hand-picked his crew, visited the top-secret atomic lab at Los Alamos that built the bomb, and coordinated many of the mission's details. Just after the bombing, Tibbets put the Enola Gay on autopilot and took a nap. It wouldn't be the last time he slept peacefully with the full knowledge of what he'd done.

Tibbets claimed in a 1989 interview that "I am supposed to have lost sleep over what I did ... I can assure you I've never lost a night's sleep on the deal." He chalked up the "flak" he'd received for his role in the bombing as "Russian propaganda." In the years after the Enola Gay dropped its payload, ushering in the nuclear age, Tibbets never expressed any guilt about it. "The morality of dropping that bomb was not my business," he said. "I was instructed to perform a military mission to drop the bomb and that was the thing I was going to do to the best of my ability."

An easy mission for the Enola Gay

Like Paul Tibbets, the man who dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, the Enola Gay's navigator, Capt. Theodore "Dutch" Van Kirk, had no regrets about his role in the bombing. He not only believed it was necessary but called the mission itself "not only a regular mission, it was an easy mission ... Everything went exactly according to plan," he recalled in an oral history interview for the World War II Museum.

Van Kirk felt the bombings not only saved American soldiers from dying if a planned invasion of Japan had gone forward — estimated U.S. losses were as high as 4 million — but also prevented many more potential Japanese casualties, which had been estimated at as many as 10 million. "I honestly believe the use of the atomic bomb saved lives in the long run," he told the Associated Press in 2005. "There were a lot of lives saved. Most of the lives saved were Japanese."

The Bockscar crew also had no regrets

At 11:02 a.m. on August 9, 1945, the B-29 Superfortress Bockscar (also written Bock's Car) arrived over Nagasaki, a Japanese port city of around 263,000 inhabitants. The plane released Fat Man, a plutonium fusion bomb different from the simpler uranium-235 bomb used on Hiroshima three days earlier. The atomic blast vaporized people near ground zero, severely burned others, and poisoned even more. At least 40,000 people died instantly.

Major General Charles Sweeney, who piloted Bockscar on his first combat mission, believed that dropping an atomic bomb was also necessary. "We had a job to do, a war to end," he wrote in his 2018 book "War's End: An Eyewitness Account of America's Last Atomic Mission." "I never questioned President Truman's decision to use every weapon at his disposal to end the bloody conflict — nor do I now." Sweeney's co-pilot on the mission, Lt. Col. Fred Olivi also felt the bombing was necessary but regretted the deaths it caused. "I took no pleasure in killing civilians," he told the Chicago Tribune.

Some crew members expressed sympathy for the dead

While Capt. Theodore Van Kirk of the Enola Gay believed the bombing of Hiroshima was necessary, he did not revel in its destruction. "I pray no man will have to witness that sight again," he said in 2005 (via the Asia-Pacific Journal). "Such a terrible waste, such a loss of life." Similarly, the Enola Gay's flight engineer, Staff Sgt. Wyatt Duzenbury, had no regrets about his participation in the bombing, but told The Atlanta Journal in 1985, "I don't think anyone can be glad when they take 100,000 lives."

Capt. Robert Lewis, the Enola Gay's co-pilot, kept a journal on the flight and after witnessing the bombing, wrote, "My God, what have we done?" — the same phrase another crew member recalled Lewis uttering during the mission. Lewis, who defended the use of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, also wrote: "If I live a hundred years, I'll never quite get these few minutes out of my mind."

One man forever changed by the bombing

On the morning of the bombing of Hiroshima, one of the B-29s, Straight Flush, was tasked with determining if the weather was suitable for bombing. The pilot, Capt. Claude Eatherly (he left the service as a major), wasn't aware the Enola Gay had an atomic bomb, but knew this was a special mission. He radioed the Enola Gay that the weather was clear. Eatherly soon learned what they had done and the knowledge haunted him for years. "I feel I killed all those people in Hiroshima," he would later tell a Veterans Administration doctor (via the Evening Star). He even reached out to the victims of Hiroshima asking for forgiveness.

After the war, Eatherly spent time in several psychiatric wards and had numerous interactions with the court system for a series of crimes ranging from writing bad checks to postal break-ins. He eventually became a vocal advocate for the anti-nuclear movement. Some claimed Eatherly was being used by the left, including Gen. Paul Tibbets. But in a series of letters (later turned into a book) between Eatherly and Günther Anders, a philosopher and antinuclear activist, Eatherly proclaimed his stance against nuclear proliferation and hoped that "someone will ... give a message that will influence the world toward a reconciliation and peace," he wrote (via "Burning Conscience: The Case Of The Hiroshima Pilot Claude Eatherly"). "You may be the man, if I can be of any help to you, count on me."