Things That Don't Make Sense About The Challenger Disaster

The history of space travel is filled with plenty of highs. The mention of space probably brought some specific mission or moment to your mind, whether that be the moon landing, the final words of the Mars Opportunity rover, or the more recent launches put on by private companies. It's the kind of thing that brings with it a sense of wonder.

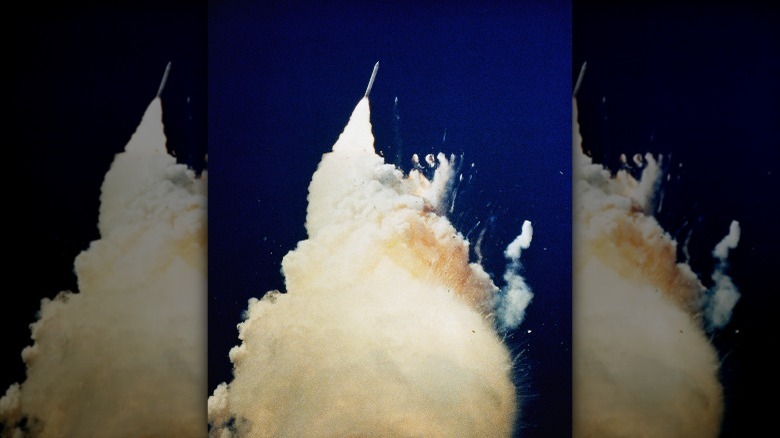

That's not to say that everything about space exploration is a spectacular sci-fi adventure, though. There's tragedy dotted throughout humanity's journey to the stars, and one of the most well known and influential of those accidents was that of the space shuttle Challenger. As the story goes, the Challenger was meant to launch from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on January 28, 1986. Just 73 seconds after launch, however, the shuttle seemed to explode in midair, killing all seven crew members on board: Francis Scobee, Michael Smith, Ellison Onizuka, Judith Resnik, Ronald McNair, Gregory Jarvis, and civilian Christa McAuliffe. Investigations into the accident revealed that the particularly low temperatures on that day essentially unsealed a joint, allowing hot gasses to leak out. Things escalated from there, leading to the apparent explosion and disintegration of the shuttle. That's the technical explanation, at least; investigations ultimately found poor decision making and management to be the root cause of the disaster.

All that said, though, there are still some hidden truths of the space shuttle Challenger and her crew, as well as some things we can't quite explain. Here are a few of them.

The last words of the crew

There's no way to know exactly what the last words of the Challenger's crew might have been, for obvious reasons. That said, there is a decent bit of audio recording that survived the fateful accident. That recording doesn't provide many answers, though. Rather, it invites new questions of its own.

If you go through the official transcript, you find a mix of what seems to be technical, procedural talk — the crewmembers calling out various readings or keeping each other informed about what they were doing at that moment — and some glimpses of their camaraderie: Judith Resnik asking for something that she succinctly describes as a "security blanket" right when the recording starts. Little jabs at Francis Scobee made by Ellison Onizuka — "Dick's thinking of somebody there" — or just their exclamations of delight, like an unattributed "Woooohoooo" shouted out about a minute after take off. (There's even a little bit of swearing that happens about 15 seconds after liftoff — thank Resnik for that one.)

But 73 seconds after launch came the chilling final words of the space shuttle Challenger's crew: Michael Smith just saying "Uh oh" before the audio cut out. To this day, people can only speculate what Smith was responding to. It was probably the moment when the crew realized something was wrong, but was there some sort of disaster in the cockpit itself, or was the pilot reacting to the explosion? It's impossible to know.

Speculation on the crew's last moments

This is one of those questions that can never be definitively answered, but there's been quite a bit of investigation and speculation when it comes to what Challenger's crew experienced in their last moments.

It's widely believed that the crew survived the initial fireball and breakdown of the shuttle; it seems like the crew compartment separated from the rest of the craft, eventually entering free fall. But that still doesn't tell us exactly what occurred in the seconds following the catastrophic failure. Official reports explained that it was possible, though not certain, that the crew lost consciousness due to the high altitudes and a loss of both cabin pressure and a steady oxygen supply. If that was the case, they probably didn't regain consciousness before hitting the water at 207 miles per hour.

All the same, though, the reports also raised the possibility that some of the crew members were at least conscious enough to activate their emergency air packs (which were, to be clear, not made to provide enough oxygen at nearly 50,000 feet in the air). Then again, that's just a guess, because investigators couldn't confirm that there had been a loss of cabin pressure. The violent impact with the ocean had effectively erased any evidence they could've used to determine what exactly had happened to the shuttle or the bodies of the Challenger's crew.

The problems were known months in advance

On the engineering end, the Challenger disaster was caused by a little piece of rubber called an O-ring. It was meant to function as a seal between different parts of the rocket boosters, but when exposed to cold temperatures (anything below 53 degrees), it couldn't expand properly or form an effective seal. That's what allowed gasses to leak out and ignite, burning through the external tanks and causing the explosion.

Here's the thing, though: None of that information about the O-rings' safe range of temperatures was discovered after the accident. All of it was known beforehand. Not only that, but engineers at NASA contractor Morton Thiokol had explicitly warned officials about the dangers long before the launch. Thiokol engineer Roger Boisjoly even said that he wrote a memo to his managers at Thiokol a full six months before the explosion. His words eerily predicted exactly what happened, mentioning "a catastrophe of the highest order" and a "loss of human life" (via NPR). But over the ensuing six months, nothing was done to address that potential safety flaw.

That seems like a mystery in and of itself, but it goes even deeper than that. In fact, there are no mentions of any such memo in official NASA documents. In other words, it's unclear how many people at NASA actually knew about the O-rings. How information like that just got lost along the way is something of a mystery on its own.

The last-minute safety discussions

The day before the Challenger launch was an eventful one, to put it lightly. That day was a very long one for NASA officials and Morton Thiokol engineers, who discussed for hours on end whether or not Challenger should even launch. The weather forecast was predicting a temperature far lower than that which Thiokol engineers believed was safe, so they wanted to call things off in the name of avoiding disaster. According to those present, the conversation went in a somewhat strange direction. The engineers were presenting data to back up their recommendations, but NASA apparently didn't think that data was decisive enough to truly convince them of the dangers. It seems clear they wanted to launch on schedule, if the multiple hours they spent grilling the engineers about their concerns tells us anything.

At that point, Thiokol executives made what engineer Roger Boisjoly called a "management decision" (via "The Challenger Disaster," edited by Sylvia Engdahl). The executives would change their stance and give the launch a green light, just to satisfy NASA and despite the engineers themselves being strongly against that choice — one that is hard to understand now, with the benefit of hindsight.

NASA officials eventually came to question their own responses. Deputy manager Judson Lovingood recalled that, after spending hours questioning Thiokol representatives about their reluctance, they didn't give the sudden change of heart any thought. "That was a mistake," Lovingood said. "We should have asked them why they'd changed their minds."

NASA was insistent on launching, but the exact reasons are murky

When Morton Thiokol engineers approached NASA managers with the recommendation to delay Challenger's launch, the responses they received were pretty cold — for example, take shuttle program manager Lawrence Mulloy's "My God, Thiokol. When do you want me to launch — next April?" (via NPR). NASA was anxious to get Challenger off the ground, but the exact reason behind that urgency has never been clear.

On one hand, it seemed like NASA might have been dealing with some perceived publicity problems. In other words, space travel wasn't cool anymore. But Challenger had presented it with a potential PR goldmine in Christa McAuliffe — the first civilian to go to space, and a teacher, at that. Suddenly, the American public cared about space again, and NASA felt like it had to make the best of the opportunity. Then, there were the goals that NASA had set for itself: namely, aggressive launch schedules to prove to everyone that the agency was reliable and that space flight could be a regular occurrence. Delays might ruin the reputation NASA officials were trying to build. There was also the possibility of political pressure. President Ronald Reagan was scheduled to give the State of the Union address that night, and the plan was for him to celebrate Challenger's launch and even phone the astronauts during the speech. There were rumors the administration had pushed NASA to go through with the launch, though White House officials vehemently denied those allegations.

All that said, no one has been forthcoming with an exact explanation of NASA's logic at that moment. PR and politics might have played roles, but official confirmation is hard to come by.

NASA proceeded despite the known dangers (and didn't learn their lesson)

Given the problems underlying the Challenger accident, psychology might be worth discussing here. After all, people who aren't involved in space travel probably see it as the kind of thing that shouldn't be approached with a careless nonchalance toward safety.

But that wasn't the case at NASA at the time, and psychologists and social scientists have weighed in with possible explanations over the years. Terms like "groupthink" have gotten tossed around, essentially contending that NASA employees just wanted to avoid disagreements and ignored the opinions of those they considered outsiders — the Morton Thiokol engineers, for example. Within that echo chamber, they also might have felt overconfident; several astronauts had died during missions, but only one American had been killed in space flight, back in 1967. Alternatively, there's the possibility that NASA had simply grown accustomed to problems with O-rings. The agency had been struggling with the parts since the 1970s, so the fact that Challenger's O-rings were a potential problem might not have raised any real red flags. Pressing onwards while disregarding known problems was just the norm.

The awful irony of this, though? NASA didn't learn anything. Safety standards did change on paper, but if you jump to the Columbia disaster in 2003, you find the same management problems. The cause of the space shuttle Columbia disaster was, once again, a known technical problem — a risk that NASA just decided to accept rather than solve.

Was there a cover-up?

The Challenger disaster had conspiracy theorists coming up with ideas that are pretty wild and almost completely unfounded. But in the years immediately following the disaster, there were reasons to believe there was a cover-up. The sporadic way that NASA released information about the crew's bodies had people thinking the agency had something to hide. But there were also incidents that called into question exactly what NASA and contractor Morton Thiokol really prioritized.

During closed hearings regarding the accident, a NASA official simply claimed that Thiokol had signed off on the launch despite concerns — an oversimplification that engineer Allan McDonald, who was sitting in on the hearing, couldn't help but dispute. As he argued, that explanation glossed over the fact that Thiokol's engineers had consistently fought to delay the launch, and that it was an executive decision — only made under intense pressure from NASA — that led Thiokol to give the green light. To him, leaving out that detail felt like intentional deception — a way for NASA to protect itself from scandal and hide the truth.

In the decades to follow, McDonald has been praised for his integrity. But right after he made his statement, Thiokol executives punished him for it, demoting him in retribution. That demotion was eventually reversed due to congressional action requiring that Thiokol allow their employees to speak freely, but, if nothing else, punishing someone for telling the truth doesn't exactly make for a great public image.

Talks about putting Big Bird on the Challenger fell through somehow

Here's a strange fact about the doomed Challenger mission: Big Bird was almost on that shuttle. Seriously — the iconic "Sesame Street" character was very nearly a crew member on Challenger. That spot — or the equivalent to it — was ultimately given to Christa McAuliffe, but the full details of that story are hazy.

In 2015, Caroll Spinney — Big Bird's longtime puppeteer — explained that he received a letter from NASA asking if he would be interested in joining the space program, taking off in a shuttle, and orbiting the Earth. It was all part of a larger push to integrate civilians into the space program and make it more popular. Using a beloved TV character was just another way to get kids interested in space – not unlike NASA's plans for McAuliffe, but with a bit more whimsy.

Clearly, the plan fell through — neither Spinney nor his famous character was present on the Challenger when it exploded — and the reasons have never been fully explained. (The effort wasn't even public knowledge until it was revealed in the 2015 documentary "I Am Big Bird.") Spinney himself has said that he suspects there just wasn't room for an 8-foot-tall puppet on a space shuttle where every square inch was potentially valuable, though there's been no official confirmation of that theory. NASA has said that those talks did take place in some capacity but only revealed that they weren't approved. The reason why is anyone's guess.

A soccer ball somehow survived the accident

Challenger's crew compartment reached a peak altitude of 65,000 feet. That's a lot of time for it to accelerate before colliding with the ocean at 207 miles per hour; it translates to 200 G's, if you're curious about the amount of force involved. That's well past the limits for the cabin itself to survive as anything more than rubble, and, morbid as it is to discuss, the impact was violent enough that the crew's remains couldn't be identified as human. And that's not even counting how the rest of the shuttle disintegrated.

And yet, a soccer ball survived all of that. Ellison Onizuka had brought the ball along because it belonged to his daughter, Janelle, who played on the soccer team at her high school — all of the athletes had even signed it just for him. Somehow, it was recovered from the wreckage and returned to Onizuka's family, with Janelle later recalling, "It was amazing, the condition it was in after the explosion" (via ABC News). Pretty incredible that a simple soccer ball made it through that.

But the soccer ball's story doesn't end there. It was put on display at the high school, but three decades later, another astronaut, Shane Kimbrough, had a daughter attending that exact school. Kimbrough offered to take up an object for the school when he flew to the International Space Station, and the soccer ball got that honor. It was photographed floating aboard the ISS in 2017.