Details That Don't Make Sense About The Devil In The Bible

Artists and filmmakers exploit him. Teenagers looking to provoke their parents indulge in music and graphic T-shirts superficially celebrating him. And of course, preachers issue warnings and admonitions against him. Even in a post-Christian world, one where organized religious belief continues to decline, the devil can still be found at all ends of culture. And belief in the devil, and Hell, is still claimed by over half of Americans. But much of what we think of when the devil's name is mentioned doesn't come from religious sources.

Take the popular image of the devil, that all-red figure with cloven hooves, pointed horns, and a fiendish goatee. It's an amalgamation of medieval morality plays, Greek mythology, brief descriptions from the Book of Revelation, and 20th-century cartoons. The pitchfork, Satan's favorite weapon and status symbol in so many depictions, was cribbed from Hades. Even the notion that the devil is the great adversary, the antagonist in the story of creation ever opposed to God, was largely developed after the books of the Bible were written.

So what does the Bible itself have to say about the devil? The answer is, at once, quite a lot and very little. Writings that later generations synthesized into the ultimate being of evil and tempter of mankind describe a range of beings with various functions and moral alignments, and when studied at the source, it can be hard to reconcile them into the force we know as Satan. Here are a few biblical passages related to the devil that don't necessarily add up.

The devil, as such, doesn't appear in the Old Testament

In the popular imagination, the devil is all over the Old Testament. Most infamously, he tempts Adam and Eve to sin through the snake in the Garden of Eden, and he challenges the Lord in the Book of Job. But in fact, there is no devil or any comparable being in the Old Testament. The word Satan appears throughout the books in the original Hebrew, but as a title, not a name.

"Satan" translates from Hebrew as "adversary" or "accuser." The term "ha-satan," used to describe several figures in the Old Testament, would literally translate to "the adversary." "Ha-satan" is how the angel of the Lord that appears before Balaam in Numbers 22 is described. The "Satan" of Job is an accuser, an angel who chastises man before God and presents tests in accordance with God's express wishes. Zechariah 3 sees the Lord rebuking Satan before the high priest Joshua in Zechariah's visions, but even here, "ha-satan" is used, implying that this is yet another "adversary" playing a prosecutorial role.

These adversarial Satans worked on God's behalf, not against him. Within Judaism, the idea of the devil as the great evil of creation was developed in the Talmud and the tradition of Kabbalah. Satan as we commonly think of him appears in the Talmud (though he's sometimes conflated with other supernatural figures), and kabbalistic texts describe the demon realm and the magical means to fight its denizens. These writings brought the Jewish conception of the devil closer to the Christian image.

The serpent of Eden was tied to the Beast of Revelation after both books were written

The first and last books of the Bible are connected, in a common interpretation, by the bestial representations of the devil. The snake who tempts Eve with the forbidden fruit is seen as Satan-come among the innocent in the Garden of Eden, and the seven-headed red dragon of Revelation 12 is a representation of the devil in a vision. But the snake is never explicitly called the devil, Satan, Lucifer, or any other name associated with the supreme evil being. It's just "the serpent," albeit a talking one, and it's punished for its part in man's downfall by the loss of its legs.

The notion of a malevolent evil being in opposition to God wasn't yet part of the Abrahamic tradition when Genesis was written. That came in later centuries, with the rise of Jewish apocalyptic literature that carried into the early Christian period. As the idea of a cosmic struggle for good and evil took root, Genesis was reinterpreted in that light, though the serpent may not have been read as the devil for some time after the books of the New Testament were written.

Revelation never ties its many-headed dragon with the serpent of Genesis. Other serpents and dragons mentioned in the Bible, such as the Leviathan of Isaiah, represented human enemies of Israel rather than supernatural ones, and fit comfortably in the family of climactic battles that paint one side as a dragon or serpent. Revelation would fit into this family too. But the silver-tongued tempter of the Garden of Eden stands apart.

2 prophecies thought to be about the devil probably aren't

The devil is often described as a fallen angel, cast out from Heaven for rebellion against God. It's the image of Satan put into poetry in "Paradise Lost." As evidence for this interpretation of the devil, some Christians point to two books of the Old Testament, Isaiah and Ezekiel. Satan doesn't appear in either book as such; both are prophetical works, concerned with threats to the kingdom of Judea. But Isaiah 14:12 to 17 and Ezekiel 28:14 to 18 are taken to describe the fall of Satan. The relevant passage in Isaiah begins: "How you have fallen from heaven, morning star, son of the dawn! You have been cast down to the earth, you who once laid low the nations!" While the passage in Ezekiel begins: "You were anointed as a guardian cherub, for so I ordained you. ... You were blameless in your ways from the day you were created till wickedness was found in you" (via Bible Gateway).

But neither passage is explicitly stated to be about the devil, and there's good reason to think neither is. Isaiah 14 was long thought to be about Satan, and it is the biblical source for the name Lucifer, the Latin translation of the Hebrew "helel," or "shining one." But while the traditional interpretation remains, scholarship from the past 200 years has favored seeing Isaiah as a challenge to the king of Babylon and Babylonian exile. And Ezekiel 28 likely refers to Ittobaal II, king of Tyre, though it's held to have a double meaning.

The devil only tempts Jesus in half the Gospels

The Gospels don't agree on some major aspects of Jesus's life. The concept of gospel harmony, wherein the four books are synthesized into a unified and more spiritually uplifting whole, can mask those differences by presenting a cohesive popular account of the story. But even for some of the devout, harmony can be a problematic way to reconcile the disparate accounts of certain events. And mixed up in these disparities is Christ's archnemesis, the devil.

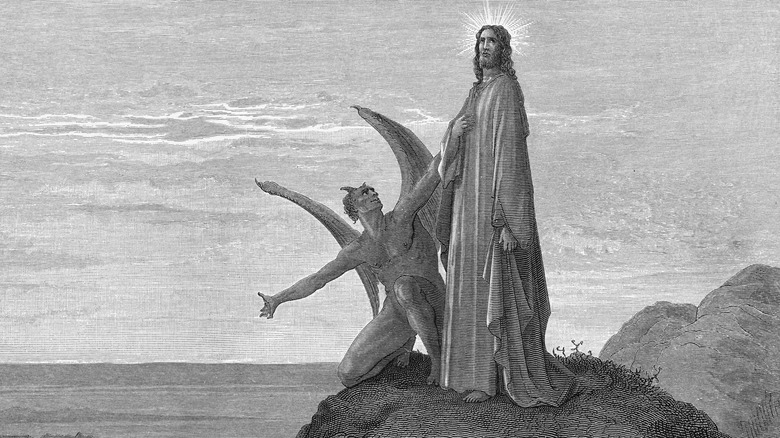

But compared to, say, the story of the Nativity, the temptation of Christ in the wilderness by Satan is relatively consistent across the Gospels. It is notable that Mark, probably the oldest of the four books, gives only a token mention of the incident. John, probably the last gospel written, doesn't include the temptation at all. In between are Matthew and Luke, which are largely in agreement with what happened: the devil came to Jesus in the wilderness and offered three temptations, and each time was rebuked by Jesus with a quote from scripture.

Other than the order the temptations appear in, Matthew and Luke line up in their accounts of the temptation. But the temptation story, and the two books as wholes, were aimed at different audiences. Matthew was primarily aimed at Jewish readers, and the temptations and responses are ordered in a way that naturally works its way toward the central notion of the Old Testament: that there is only one Lord God. Luke was more for gentiles and the reordered temptations may reflect his focus on Jesus undoing the sins and temptations of all humanity.

Is the idea of the devil blasphemy?

Theologians and historians can argue over whether the devil really appears in the Old Testament, or just what he said to Jesus in the wilderness. But there's a more fundamental problem with the idea of the devil: that an all-powerful, all-loving God should allow such a malevolent being to exist, and that said being should be able to tempt and torment mankind at every turn. Does the very concept of the devil make sense, then, in the Bible? There is a school of thought within Judaism that regards the Christian idea of Satan as the great evil to be blasphemous; it must be — it is argued — because otherwise, God's hand would not be behind all things, good or bad.

The problem of evil is one of the great questions in Christianity, and even clergymen and apologetics have conceded that it's one of the strongest arguments against the Christian God's existence. To answer the question, writers have gone through the Bible and reinterpreted many of the contentious passages mentioned here as supporting the view of a devil who is the great enemy of man, constantly tempting us, but still a created being who was defeated by the sacrifice of Jesus. They also lean into the view of Satan as a fallen angel, originally created good but rebellious through an act of free will. Why he's allowed to keep rebelling even after the crucifixion has been explained as a showcase for the glory of God, or something that is only temporary for earthly existence. Whether that's a satisfying answer is another matter; as Christians say, God works in mysterious ways.