Things That Don't Make Sense About The Disaster Of Pompeii

Before Pompeii became a historic site, the bustling port city, which sat on the Bay of Naples, was a popular resort destination for elites and an abundant agricultural powerhouse. By A.D. 79, tens of thousands of people lived in Pompeii and the surrounding area. All lived within sight of the mountain known as Vesuvius.

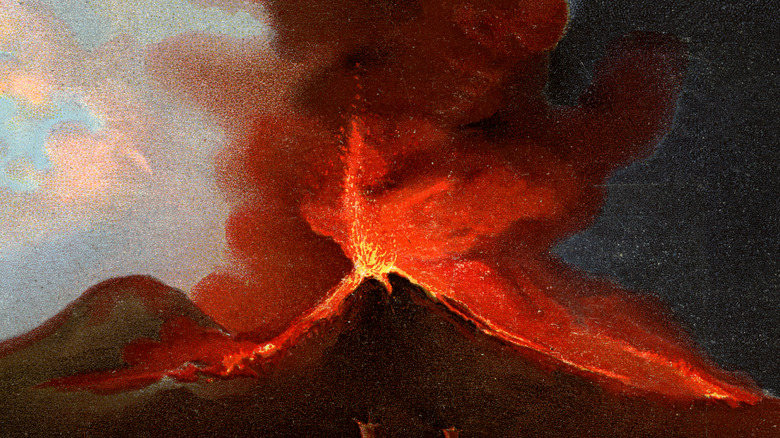

Then, Vesuvius erupted. Minor earthquakes had occurred prior, but inhabitants reportedly shrugged these off as a fact of life in the region. Less normal was the sudden explosion of ash, rock, and gas that issued from the mountain in a massive column, and then rained down upon the people below. Many escaped, but others were trapped beneath an ash fall that grew to more than 20 feet deep in places. The next day, the still-ongoing eruption produced one final but very fatal blow: a pyroclastic flow. This superheated rush of gas and rock barreled down the mountain at hundreds of miles per hour, abruptly killing anything in its path (and essentially turning at least one man's brain to glass). An estimated 2,000 people died in Pompeii, but the regional death toll was about 16,000.

The city lay mostly buried until the first serious excavations began in the mid-18th century. Even today, archaeologists are still uncovering new finds about this ancient city and its inhabitants. Yet, there are some things that are still confusing and even nonsensical about the disaster of Pompeii, from how the people saw Vesuvius to what they did in the aftermath of the eruption.

Why did some ancient people ignore the warning signs?

The inhabitants of Pompeii and nearby settlements like Herculaneum almost certainly had warnings that something was going on with their local volcano. However, the ancient Romans neither had advanced seismological equipment nor our modern understanding of how volcanoes like Vesuvius work — namely, that it erupts periodically and that eruptions probably will be preceded by increased activity like earthquakes. But contemporary accounts make it clear that people noticed changes in the mountain.

Writing more than a century later, Cassius Dio wrote that locals had reportedly seen giants on the mountain, followed by earthquakes and loud rumbling from the ground. The so-called giants may have actually been plumes of gas emitted from the mountain which, when spotted from far off, may have fit the bill of boisterous, destructive creatures in the Roman imagination.

It's not obvious how everyday Pompeians reacted to these signs. Clearly, they elicited some amount of fear, but there's good evidence that buildings — and even water pipes — in Pompeii and the surrounding area had been or were in the process of being repaired at the time of the A.D. 79 eruptions. The damage may well have been the result of recurrent earthquakes, like a fairly large and destructive one that struck the area in A.D. 62. But, while some people had already left Pompeii as a result of what were probably increasing geological disturbances, others may not have been willing to leave the lucrative environment of the bustling city.

No one's totally sure when Vesuvius erupted

The fateful day of the eruption was long believed to be August 24, A.D. 79, in the waning days of summer, going by the accounts of ancient writers who related stories of the disaster. Namely, they were going by the account of Pliny the Younger, who offers up the only eyewitness account of the eruption in two letters to Roman politician and historian Tacitus.

But Pliny's account, which includes the dramatic evacuation attempt undertaken by his uncle Pliny the Elder (as well as the older man's presumed death in the eruption), may not be fully accurate. While Pliny the Younger observed the eruption from a much safer vantage point across a bay of water, he may have been so overcome that he got the dates wrong. Or, given that it was written about two decades after the events of the disaster, Pliny may have simply misremembered. Centuries later, among the ruins of Pompeii's surprising graffiti, archaeologists found one inscription written on a wall in charcoal. It included a date that, according to our modern calendar system, puts the inscription in mid-October. Given how easily the charcoal would have come off the wall, chances are that it was set down shortly before the eruption buried it in ash and other debris.

For many, this revelation cinched long-held suspicions, given how other excavators found evidence of heating systems in use and the consumption of harvested fruits that didn't jive with a summer date.

Why wasn't evacuation by water more successful?

For many who learn about the disaster of Pompeii, there's one obvious question hanging over the proceedings: why didn't people escape by water? It was a seaside resort on the Bay of Naples, and not only was open water right there while a fiery volcano rained down ash and other debris, but there were also docks and ships that could get people out of town. So, why have archaeologists uncovered human remains in the shoreside boathouses of nearby Herculaneum?

The explanation may have had something to do with the weather. For starters, waters in the bay were normally rough and may have been made all the more choppy with ground-trembling earthquakes. Then, there were the winds. Pliny the Younger wrote in his account of the eruption that winds blowing inland kept some boats from leaving, though he added: "This wind, of course, was fully in my uncle's favor and quickly brought his boat to Stabiae" near Pompeii, where he intended to rescue people. Yet, had Pliny the Elder not reportedly died from inhaling volcanic fumes — as his compatriots later told Pliny the Younger — he might have found that it was exceedingly difficult to leave the shore, at least as long as the winds were blowing.

Meanwhile, it's possible that some waterways would have been eventually choked and crushed by falling pumice, ash, and other debris. Perhaps some, like the people found in Herculaneum's boathouses, may have discovered this or that there simply weren't enough boats for everyone to leave all at once.

We don't quite know how big the eruption was

For such a dramatically destructive event that killed thousands and buried multiple cities beneath feet of ash and pumice, it's odd we don't know how large the eruption of Vesuvius was in A.D. 79.

Today, one common measure of a volcano's power is its volcanic explosivity index, or VEI. A relatively gentle effusive eruption with low-viscosity lava and little pressure, such as from Hawaii's Kilauea, gets a VEI of 0. Meanwhile, the infamous 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, which effectively blew about one-third of the mountain off and is the most powerful eruption in U.S. history, gets a 5. The highest VEI rating of 8 is reserved for nigh-apocalyptic supervolcanoes, which could have devastating effects like the eruption of the Yellowstone caldera caused an estimated 640,000 years ago.

But given how long ago the A.D. 79 eruption took place, volcanologists can only give us their best guess. The Smithsonian Institution's Global Volcanism Program gives that eruption a tentative VEI of 5, but the lack of concrete data or on-the-ground eyewitness reports makes it tricky. Though the exact scale of the eruption isn't easy to pin down, there's little doubt that it was enormous (but thankfully not apocalyptic). Pliny the Younger's account indicates that Vesuvius was actively erupting for more than 18 hours and created a tremendous mushroom cloud that ballooned above the landscape for miles (to be more precise, he likened it to the shape of an umbrella pine).

Why did the people around Vesuvius have such good teeth?

The reality of ancient dental health may not be as bad as you think it might be, given that not everyone had access to decay-inducing sugary food, but neither was it up to most modern standards. At least the people of ancient Rome did have access to some basic dental treatments, but painful dental conditions still happened.

But ancient dentists may have had a difficult time getting work in Pompeii. When modern archaeologists uncovered victims of the disaster, they found that the ancient people of the city had unusually good teeth for the time. If it weren't for the falling debris, pyroclastic flows, and smothering ash, they would have been pretty darn lucky. As for why, one reason is likely because many Pompeians ate a low-sugar diet, but another unlikely benefactor is Vesuvius itself.

The geological system that produced the volcano appears to have introduced fluorine into the local water system. Somewhat like fluoridated water today, it could have helped stave off tooth decay by strengthening tooth enamel and remineralizing teeth. But, as those who live near active volcanoes today sometimes learn, there's a dark side to all that fluorine. According to a 2011 paper published in PLoS One, the ancient residents of the area around Pompeii appear to have at least occasionally suffered from skeletal fluorosis caused by the presence of fluoride and fluorine. With time, this condition can weaken bones and cause painful damage to the joints.

Where are the other firsthand accounts of the disaster?

There is only one known firsthand account of the Pompeii disaster, written by Pliny the Younger. What gives? Scholars estimate the literacy rate of ancient Rome was 15%, though that number could vary depending on when and where you were. In Pompeii, given the well-appointed villas excavated by modern archaeologists, it's obvious that at least some elites lived in the city. It stands to reason that a number of those upper-class people would have known to read and write. If even one or two of that group managed to escape, then they surely could have found a pen and paper to scribble down what happened.

Yet, at least for now, we only have Pliny's account of what he saw from across the Bay of Naples, written about 20 years after the eruption. Perhaps there is another account hidden somewhere else or a Pompeian refugee did write their recollections down, all lost to time on crumbling fragments of papyrus.

Or maybe, just maybe, it's in the Bible. This is a serious long shot, but biblical scholar James Tabor suggests that the Book of Revelation's terrifying apocalyptic imagery may include a coded account of the eruption (via The Bart Ehrman Blog). He contends that the fall of Babylon described in the text is potentially a description of how the port city of Pompeii was consumed by volcanic destruction as its louche inhabitants faced God's divine wrath.

Why didn't people understand that Vesuvius would erupt again?

While there were certainly no ancient Roman seismologists trekking up the sides of volcanoes with advanced scientific equipment and degrees in geology, there were intelligent and curious observers amongst them. Some turned their minds to the odd history of Vesuvius, though the last eruption had taken place around 216 B.C., as far as geologists today can tell.

In Strabo's Geography (written about five decades before the eruption that destroyed Pompeii), the ancient geographer describes the barren, burned summit of Vesuvius that loomed above rich fields below. Meanwhile, Diodorus Siculus wrote that Vesuvius still showed the marks of a great, fiery past. Supposedly, it was also witness to a long-ago battle between the hero Heracles and a group of massive, boisterous giants.

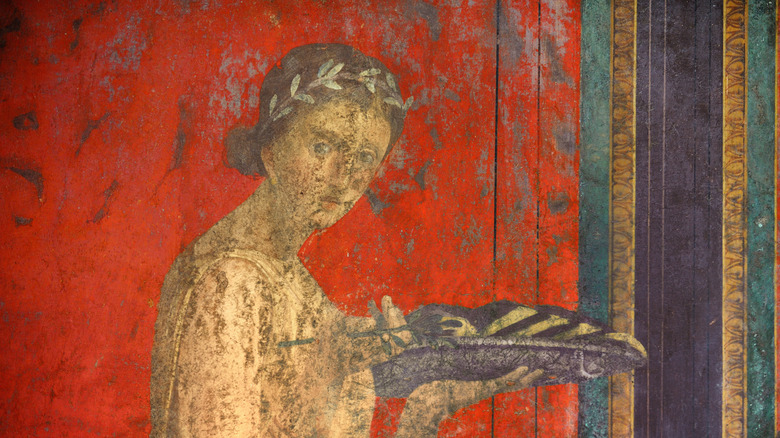

But while there may have been a cultural memory of a fiery, even eruptive Vesuvius, it's not clear just how much people understood the possibility that it could erupt again. After all, there were the busy cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, as well as the surrounding rich farmlands, all filled with people who didn't seem that worried about the local mountain. People barely mention the volcano in writings around the time, and so far only one fresco uncovered in Pompeii appears to depict Vesuvius (showing a more complete peak that was likely blown apart in the eruption). To some, at least, their misunderstanding meant they regarded Vesuvius as an innocuous part of the landscape instead of a disaster waiting to happen.

Why don't we know more about Pompeii's refugees?

It's clear that some people were able to escape Pompeii before destruction obliterated the city and its environs, though it's difficult to get a sense of just how many people survived. Most estimates account for around 13,000 survivors from a pre-eruption population of 15,000, given that about 2,000 sets of remains have been found by modern archaeologists in the ruins of Pompeii and nearby Herculaneum. Still, with population numbers not exactly accurate — after all, the disaster happened nearly two millennia ago — that number remains a pretty broad estimate.

The more tricky thing, however, is figuring out exactly where those survivors went and what they did after the eruption. In the aftermath, it appears that nearby settlements that were relatively unaffected, such as Naples and Ostia, began to expand. It stands to reason that at least some of the survivors traveled to the closest stable area and put down stakes there. They may have even had family connections in these towns that made finding a spare room to sleep in a bit easier.

Nonetheless, inconsistencies in family names and addresses make it hard for researchers to tease out specifics. The most recent effort undertaken by classics professor Steven L. Tuck, which compares Roman inscriptions with unique names associated with the Pompeii region, found more than 200 likely survivors (via The Conversation). It's a great advance, to be sure, but still leaves thousands of likely refugees whose movements and motivations remain hidden to us.

Post-eruption activity in the city gets confusing

Given that Pompeii was buried in an estimated 19 to 23 feet of ash and pumice, it's not as if anyone expected to move right back in once Vesuvius had stopped rumbling. But there is evidence that, not long after the disaster, people returned to the ash-choked city. Why someone would do such a thing while the city was newly devastated doesn't necessarily make sense ... until you consider what went missing.

Centuries later, archaeologists have uncovered evidence of people who dug through the ashes and broke into damaged structures throughout Pompeii. Whether they were homeowners looking to get back some of their goods or looters who hoped to profit from the tragedy isn't clear. But some of them were certainly methodical. In the ancient period, some of the tunneled entrances were marked as leading to already-searched homes, indicating that recovery or looting had left the inside barren. The skeletal remains of other individuals, perhaps less careful than they could have been, have been found in the ruined city lying alongside excavation equipment. One of the most likely guesses is that they died in a tunnel collapse.

Otherwise, it appears that most people, likely confused by the notion of returning to the ruined city, had the better sense to stay above ground and away from what had become the graveyard of Pompeii. Though the allure of buried treasure clearly overcame some morals, to others such a motivation didn't make any sense.

Why do so many people blame the inhabitants of Pompeii?

In the long aftermath of the disaster of Pompeii, it's become somewhat fashionable to blame the dead for their own fate. If only they had been smarter and wiser, they would have sensibly left the city early and abandoned their heavy valuables. And that is arguably the most confusing thing about many modern descriptions of Pompeii's destruction, which make it seem as if people sat dumbly in their homes, guarding their property and waiting for the eruption to end.

But in one house, the remains of a heavily pregnant person and 11 others were found, hinting that a young woman close to giving birth could not simply run away and that members of her family stayed to support her. The bones of another man — who appears to have died in the superheated pyroclastic flow that came barreling down the slopes of Vesuvius — showed a limb disability that would have made it difficult for him to walk.

Other victims may have been likewise caring for vulnerable people, been vulnerable themselves, or could have been too poor to quickly pack up and leave their meager livelihood. Given the presence of enslaved people in the city (and amongst the dead), it's also possible that some weren't given the choice to save themselves and were instead ordered to stay with their masters. The evidence suggests that perfectly intelligent and capable people were trapped there by circumstance, rather than by any fault of their own.